Appendix 1 Film Festivals in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administration of Barack Obama, 2015 Remarks at a State Dinner Hosted

Administration of Barack Obama, 2015 Remarks at a State Dinner Hosted by President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya in Nairobi, Kenya July 25, 2015 President Kenyatta. Thank you very much, Amina. And I appreciate your sentiments. President Barack Obama, President Mwai Kibaki, our distinguished visitors, distinguished guests: Let me begin once again, as I have said severally since the start of this visit, on behalf of the people of the Republic of Kenya, that we are once again delighted to welcome you to this country and to this city. And I know and strongly believe that you have felt the warmth of our people and, indeed, especially you, President Obama, the tremendous joy at your presence here with us in Nairobi and in Kenya. Welcome and welcome again. Mr. President, this is not your first trip to Kenya. And indeed, we have heard severally, Amina has just mentioned, and you yourself have told us that you have been here. But yesterday you returned riding on the wings of history as a President of historic consequence for America, for Africa, and most importantly, for Kenya. As a world leader who has grappled with great challenges of this age and as a builder of bridges, and to you once again, we say, karibu na sana Kenya. The people of Kenya and the United States share such an abiding love of freedom that we have made grim sacrifices to secure it for our children. We then chose to weave our diverse cultures into a national tapestry of harmonious coexistence. Our paths have not been easy. -

5Bfbeeac3776649f9b212fdfb326

5 Foreword raymond Walravens 9 opening and Closing Ceremony / awards 10 world Cinema Amsterdam Competition 20 mexiCan landsCapes Features 22 new mexiCan Cinema presentation paula Astorga riestra 24 postCards From a new mexiCan Cinema Carlos BonFil 42 mexiCan landsCapes shorts 46 speCial sCreenings (out oF Competition) 51 speCials 55 world Cinema Amsterdam open Air 62 world Cinema Amsterdam on Tour 63 we would like to thank 67 index Filmmakers A – Z 69 index Films A – Z 70 sponsors and partners Foreword From 12 through 22 August, the best independently world Cinema Amsterdam Competition produced films from Latin America, Asia and Africa The World Cinema Amsterdam competition programme will be brought together in one festival: World Cinema features nine truly exceptional films, taking us on a Amsterdam. fascinating odyssey around the world in Chad, South Africa, Thailand, Malaysia, Turkey, the Philippines, World Cinema Amsterdam is a new initiative by Argentina, Mexico and Nicaragua, and presenting work independent art cinema Rialto, which for many years both by filmmakers who have more than earned their has been promoting the presentation of films and spurs and debut films by young, talented directors. filmmakers from Africa, Asia and Latin America. Award winners from renowned foreign festivals such as Cannes or Berlin, and films that have captured our In 2006, Rialto started working towards the realization attention elsewhere will have their Dutch or Amsterdam of its long-cherished dream: to set up a festival of its premieres during the festival. own dedicated to presenting the many pearls of world The most recent productions by the following cinema. -

Co-Produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the Vision

Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the vision. the voice. From LA to London and Martinique to Mali. We bring you the world ofBlack film. Ifyou're concerned about Black images in commercial film and tele vision, you already know that Hollywood does not reflect the multi- cultural nature 'ofcontemporary society. You know thatwhen Blacks are not absent they are confined to predictable, one-dimensional roles. You may argue that movies and television shape our reality or that they simply reflect that reality. In any case, no one can deny the need to take a closer look atwhat is COIning out of this powerful medium. Black Film Review is the forum you've been looking for. Four times a year, we bringyou film criticiSIn froIn a Black perspective. We look behind the surface and challenge ordinary assurnptiorls about the Black image. We feature actors all.d actresses th t go agaul.st the graill., all.d we fill you Ul. Oll. the rich history ofBlacks Ul. Arnericall. filrnrnakul.g - a history thatgoes back to 19101 And, Black Film Review is the only magazine that bringsyou news, reviews and in-deptll interviews frOtn tlle tnost vibrant tnovetnent in contelllporary film. You know about Spike Lee butwIlat about EuzIlan Palcy or lsaacJulien? Souletnayne Cisse or CIl.arles Burnette? Tllrougll out tIle African cliaspora, Black fi1rnInakers are giving us alternatives to tlle static itnages tIlat are proeluceel in Hollywood anel giving birtll to a wIlole new cinetna...be tIlere! Interview:- ----------- --- - - - - - - 4 VDL.G NO.2 by Pat Aufderheide Malian filmmaker Cheikh Oumar Sissoko discusses his latest film, Finzan, aself conscious experiment in storytelling 2 2 E e Street, NW as ing on, DC 20006 MO· BETTER BLUES 2 2 466-2753 The Music 6 o by Eugene Holley, Jr. -

South Africa: Afrikaans Film and the Imagined Boundaries of Afrikanerdom

A new laager for a “new” South Africa: Afrikaans film and the imagined boundaries of Afrikanerdom Adriaan Stefanus Steyn Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Social Anthropology in the faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Bernard Dubbeld Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology December 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract The Afrikaans film industry came into existence in 1916, with the commercial release of De Voortrekkers (Shaw), and, after 1948, flourished under the guardianship of the National Party. South Africa’s democratic transition, however, seemed to announce the death of the Afrikaans film. In 1998, the industry entered a nine-year slump during which not a single Afrikaans film was released on the commercial circuit. Yet, in 2007, the industry was revived and has been expanding rapidly ever since. This study is an attempt to explain the Afrikaans film industry’s recent success and also to consider some of its consequences. To do this, I situate the Afrikaans film industry within a larger – and equally flourishing – Afrikaans culture industry. -

Shakespeare and the Holocaust: Julie Taymor's Titus Is Beautiful, Or Shakesploi Meets the Camp

Colby Quarterly Volume 37 Issue 1 March Article 7 March 2001 Shakespeare and the Holocaust: Julie Taymor's Titus Is Beautiful, or Shakesploi Meets the Camp Richard Burt Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 37, no.1, March 2001, p.78-106 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Burt: Shakespeare and the Holocaust: Julie Taymor's Titus Is Beautiful, Shakespeare and the Holocaust: Julie Taymor's Titus Is Beautiful, or Shakesploi Meets (the) Camp by RICHARD BURT II cinema eI'anna piu forte (Cinema is the strongest weapon) -Mussolini's motto Every day I'll read something that is right out of Titus Andronicus, so when people think this is "over the top," they're absolutely wrong. What could be more "over the top" than the Holocaust? -Julie Taymor "Belsen Was a Gas." -Johnny Rotten SHAKESPEARE NACH AUSCHWITZ? NE MORNING in the summer of 2000, I was channel surfing the trash talk O. shows to get my daily fix of mass media junk via the hype-o of my tele vision set. After "Transsexual Love Secrets" on Springer got a bit boring, I lighted on the Maury Povich Show.! The day's topic was "My seven-year-old child drinks, smokes, swears, and hits me!" Father figure Pavich's final solu tion, like Sally Jessie Raphael's with much older kids on similar episodes of her show, was to send the young offenders to boot camp. -

Videos in Motion

Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” Dipartimento di Studi e Ricerche su Africa e Paesi Arabi Tesi di Dottorato di Ricerca in Africanistica, IX ciclo - Nuova Serie VIDEOS IN MOTION Processes of transnationalization in the southern Nigerian video industry: Networks, Discourses, Aesthetics Candidate: Alessandro Jedlowski Supervisor: Prof. Alessandro Triulzi (University of Naples “L’Orientale”) Co-supervisor: Prof. Jonathan Haynes (Long Island University – New York) Academic Year 2010/211 Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” Dipartimento di Studi e Ricerche su Africa e Paesi Arabi Tesi di Dottorato di Ricerca in Africanistica, IX ciclo - Nuova Serie VIDEOS IN MOTION Processes of transnationalization in the southern Nigerian video industry: Networks, Discourses, Aesthetics Candidate: Alessandro Jedlowski Supervisor: Prof. Alessandro Triulzi (University of Naples “L’Orientale”) Co-supervisor: Prof. Jonathan Haynes (Long Island University – New York) Academic Year 2010/2011 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS P. 5 INTRODUCTION. Videos in motion P. 16 CHAPTER I. Defining the field of enquiry: History, concepts and questions P. 40 SECTION I. Beyond the video boom: Informal circulation, crisis of production and processes of transnationalization in the southern Nigerian video industry P. 45 CHAPTER II. Regulating mobility, reshaping accessibility: The production crisis and the piracy scapegoat. P. 67 CHAPTER III. From Nollywood to Nollyworld: Paths of formalization of the video industry’s economy and the emergence of a new wave in Nigerian cinema P. 87 SECTION II. The “Nollywoodization” of the Nigerian video industry: Discursive constructions, processes of commoditization and the industry’s transformations. P. 93 CHAPTER IV. When the Nigerian video industry became “Nollywood”: Naming and branding in the videos’ discursive mobility. -

Cinema and New Technologies: the Development of Digital

CINEMA AND NEW TECHNOLOGIES: THE DEVELOPMENT OF DIGITAL VIDEO FILMMAKING IN WEST AFRICA S. BENAGR Ph.D 2012 UNIVERSITY OF BEDFORDSHIRE CINEMA AND NEW TECHNOLOGIES: THE DEVELOPMENT OF DIGITAL VIDEO FILMMAKING IN WEST AFRICA by S. BENAGR A thesis submitted to the University of Bedfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2012 2 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................. 5 LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................ 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ...................................................................................... 7 DEDICATION: ....................................................................................................... 8 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................ 9 ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................... 13 Chapter One: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Key Questions of the Research ................................................................... 14 1.2 Methodologies ............................................................................................. 21 1.3 Context: Ghana and Burkina Faso .............................................................. 28 1.4 Context: Development of Film Cultures .................................................... -

Robert Burns Centre FILM THEATRE BOX OFFICE 01387 264808 MAY to JULY 2011

Robert Burns Centre FILM THEATRE BOX OFFICE 01387 264808 WWW.RBCFT.CO.UK MAY to JULY 2011 29APRIL 07MAY 2011 INCLUDING DUMFRIES FILM FESTIVAL in local cinemas across the region PIRATES OF THE PROGRAMME CARIBBEAN Submarine Source Code Armadillo Essential Killing The African Queen 13 Assassins The Conspirator Welcome Welcome to the fifth Dumfries Film Festival – an intense week of film across Dumfries and Galloway with local cinema screenings in Dumfries, Moffat, Annan and the Isle of Whithorn. We’ve been on a diet since last year’s bumper food themed festival and have slimmed down a bit (less funding these days). Focussing on quality rather than quantity we have a fantastic array of films, quizzes and events to entertain all ages with a special youth strand running though the week – young programmers, young characters, young production companies and films for young people (and for all of us still young at heart too). We hope that you will you will spring into film and enjoy! Fiona Wilson (Film Officer) and Darren Connor (Guest Programmer) …….filling in for Film Officer Alice Stilgoe who while on maternity leave enjoying quality time with baby girl Bonnie, still managed to do sterling work programming most of this festival for your enjoyment. 29APRIL 07MAY 2011 Young Programmers’ Forum Spring 2011: Alex Bryant • Cameron Forbes • Luke Maloney • Connor McMorran • Ruth Swift-Wood • David Barker • Tom Archer • Lauren Halliday • Beth Ashby • Danielle Welsh • James Pickering Four Young Programmer’s Choice screenings at RBCFT are the culmination of a six-week course for young people aged 16-24 that explored film programming. -

ADB, Myanmar Sign $3M Relief Grant for Disaster-Hit Areas

Volume II, Number 135 4th Waning Day of Wagaung 1377 ME Thursday, 3 September, 2015 PERSPECTIVES I will do my utmost to carry out the peace Presidential Making the case for delegation in inflation-adjusted process, just as I have been during presidency Beijing salaries PAGE 2 PAGE 3 PAGE 8 ADB, MYANMAR SIGN $3M RELIEF GRANT FOR DISASTER-HIT AREAS By Ye Myint YANGON — The Asian Devel- opment Bank and the Govern- ment of Myanmar on Wednes- day inked a US$3 million grant agreement to help communities affected by the recent flooding and landslides in the country’s 12 of 14 regions and states. The signing ceremony of the grant agreement for Myanmar’s flood emergency response project took place in Nay Pyi Taw. U Maung Maung Win, Per- manent Secretary of the Ministry of Finance, and Mr. Winfried Wicklein, ADB’s Myanmar Country Director, signed the grant agreement in the presence of Deputy Ministers for Finance Dr Lin Aung and Dr Maung Maung Thein. “The ADB funds are very timely as the government and its partners are still addressing the immediate needs of the crisis, while preparing a smooth tran- sition to the recovery phase. In addition, the risk of further mon- soon rains and associated damage remains,” U Maung Maung Win said. The ADB approved the A family uses a boat to pass through Yay Tar Gyi village in Kyaunggon Township in Ayeyarwady Region on 25 August.—PHOTO: OCHA/C.HYSLOP emergency grant to finance flood relief efforts in Myanmar in late munities, ADB said. national and state and regional flooding, landslides and wind claimed more than K1.6 bil- August. -

Interpretation in Recent Literary, Film and Cultural Criticism

t- \r- 9 Anxieties of Commentary: Interpretation in Recent Literary, Film and Cultural Criticism Noel Kitg A Dissertàtion Presented to the Faculty of Arts at the University of Adelaide In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 7994 Nwo.rà"o\ \qq5 l1 @ 7994 Noel Ki^g Atl rights reserved lr1 Abstract This thesis claims that a distinctive anxiety of commentary has entered literary, film and cultural criticism over the last thirty years/ gathering particular force in relation to debates around postmodernism and fictocriticism and those debates which are concerned to determine the most appropriate ways of discussing popular cultural texts. I argue that one now regularly encounters the figure of the hesitant, self-diiioubting cultural critic, a person who wonders whether the critical discourse about to be produced will prove either redundant (since the work will already include its own commentary) or else prove a misdescription of some kind (since the criticism will be unable to convey the essence of , say, the popular cultural object). In order to understand the emergence of this figure of the self-doubting cultural critic as one who is no longer confident that available forms of critical description are adequate and/or as one who is worried that the critical writing produced will not connect with a readership that might also have formed a constituency, the thesis proposes notions of "critical occasions," "critical assemblages," "critical postures," and "critical alibis." These are presented as a way of indicating that "interpretative occasions" are simultaneously rhetorical and ethical. They are site-specific occasions in the sense that the critic activates a rhetorical-discursive apparatus and are also site-specific in the sense that the critic is using the cultural object (book, film) as an occasion to call him or herself into question as one who requires a further work of self-stylisation (which might take the form of a practice of self-problematisation). -

Sydney Film Festival 6-17 June 2012 Program Launch

MEDIA RELEASE Wednesday 9 May, 2012 Sydney Film Festival 6-17 June 2012 Program Launch The 59th Sydney Film Festival program was officially launched today by The Hon Barry O’Farrell, MP, Premier of NSW. “It is with great pleasure that I welcome the new Sydney Film Festival Director, Nashen Moodley, to present the 2012 Sydney Film Festival program,” said NSW Premier Barry O’Farrell. “The Sydney Film Festival is a much-loved part of the arts calendar providing film-makers with a wonderful opportunity to showcase their work, as well as providing an injection into the State economy.” SFF Festival Director Nashen Moodley said, “I’m excited to present my first Sydney Film Festival program, opening with the world premiere of the uplifting Australian comedy Not Suitable for Children, a quintessentially Sydney film. The joy of a film festival is the breadth and diversity of program, and this year’s will span music documentaries, horror flicks and Bertolucci classics; and the Official Competition films made by exciting new talents and masters of the form, will continue to provoke, court controversy and broaden our understanding of the world.” “The NSW Government, through Destination NSW, is proud to support the Sydney Film Festival, one of Australia’s oldest films festivals and one of the most internationally recognised as well as a key event on the NSW Events Calendar,” said NSW Minister for Tourism, Major Events and the Arts, George Souris. “The NSW Government is committed to supporting creative industries, and the Sydney Film Festival firmly positions Sydney as Australia’s creative capital and global city for film.” This year SFF is proud to announce Blackfella Films as a new programming partner to jointly curate and present the best and newest Indigenous work from Australia and around the world. -

Catalogue2007.Pdf

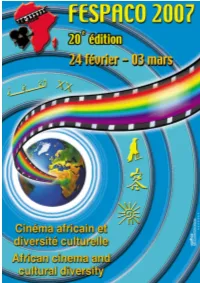

Sommaire / Contents Comité National d'Organisation / The National Organising Committee 6 Mot du Ministre de la Culture des Arts et du Tourisme / Speech of the Minister of Culture, Arts and Tourism 7 Mot du président d'honneur / Speech of honorary chairperson 8 Mot du Président du Comité d'Organisation / Speech of the President of the Organising Committee 9 Mot du Président du Conseil d’Administration / / Speech of the President of Chaireperson of the Board of Adminsitration 11 Mot du Maire de la ville de Ouagadougou / Speech of the Mayor of the City of Ouagadougou 12 Mot du Délégué Général du Fespaco / Speech of the General Delegate of Fespaco 13 Regard sur Manu Dibango, président d'honneur du 20è festival / Focus on Manu Dibango, Chair of Honor 15 Film d'Ouverture / Opening film 19 Jury longs métrages / Feature film jury 22 Liste compétition longs métrages / Competing feature films 24 Compétition longs métrages / Feature film competition 25 Jury courts métrages et films documentaires / Short and documentary film jury 37 Liste compétition courts métrages / Competing short films 38 Compétition courts métrages / Short films competition 39 Liste compétition films documentaires / Competing documentary films 49 Compétition films documentaires / Documentary films competition 50 3 Liste panorama des cinémas d'Afrique longs métrages / Panorama of cinema from Africa - Feature films 59 Panorama des cinémas d'Afrique longs métrages / Panorama of cinema from Africa - Feature films 60 Liste panorama des cinémas d'Afrique courts métrages / Panorama