South Africa: Afrikaans Film and the Imagined Boundaries of Afrikanerdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 13, 2016 Volume Xiv, Issue 12

THE JAMESTOWN FOUNDATION JUNE 13, 2016 VOLUME XIV, ISSUE 12 p.1 p.3 p.6 p.8 Alexander Sehmer Abubakar Siddique Jessica Moody Wladimir van Wilgenburg BRIEFS Taliban Victories in The Niger Delta U.S. Backing Gives Helmand Province Avengers: A New Kurds Cover for United Prove Test for Afghan Threat to Oil Produc- Federal Region in Government ers in Nigeria Northern Syria LIBYA: CLOSING IN ON ISLAMIC STATE’S STRONG- battle ahead. IS is thought to have heavily fortified Sirte. HOLD The advancing forces will face thousands of fighters and potentially suicide bombers and Improvised Explosive Alexander Sehmer Devices (IEDs). There also remains the question of just how unified an assault will be. The Misratan-led forces Libyan forces have had a run of luck against Islamic have been brought together under the Bunyan Marsous State (IS) fighters in recent weeks, with two separate Operations Room (BMOR), established by Prime Minis- militias capturing several towns and closing in on the ter Faiez Serraj, head of the Government of National extremists’ stronghold of Sirte. Accord (GNA) (Libya Herald, June 8). According to BMOR, they are working with the PFG. Amid Libya’s The Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG), the unit set up to fractious politics, however, it is unlikely to be that sim- protect Libya’s oil installations, took control of the town ple. of Ben Jawad on May 30 and moved on to capture Naw- filiyah, forcing IS fighters back towards Sirte (Libya Her- The PFG is not a natural ally for the Misratans, and the ald, June 1). -

September 2, 2020 TO

7772 N. Palm Ave. Fresno, CA 93711 (559) 457-0681 p. (559) 457-0318 f. FresnoCountyRetirement.org DATE: September 2, 2020 TO: Board of Retirement FROM: Donald C. Kendig, CPA, Retirement Administrator Staff Contact: Conor Hinds, Supervising Accountant SUBJECT: Receipt and Filing of the Equity Investment Manager Annual Proxy Voting – RECEIVE AND FILE Recommended Action 1. Receive and File. Fiscal and Financial Impacts There are no fiscal impacts to receiving the annual investment manager proxy voting reports as an informational item. Background and Discussion Prior to February 2003 FCERA had contracted with International Shareholder Services (ISS) to provide proxy voting services in order to exercise the right on behalf of the Board to respond timely and accurately to domestic and international proxy voting requests with the focus on maximizing shareholder value. At the February 5, 2003 Board of Retirement meeting, the Board voted unanimously to allow the ISS contract to expire and to allocate the responsibility of proxy voting to the investment managers as these services were already available under the normal management fee structure. The Board’s decision saves approximately $50,000 annually. As a result of the shift in responsibility of proxy voting to the investment managers, the Investment Policy Statement was revised and now states the Board’s authority in this area and sets the expectation for the proxy voting process by the investment managers. In keeping with the Board’s Investment Policy Statement, FCERA staff has obtained the proxy voting records of our current domestic and international equity managers. Attached for your review is the most recent proxy voting reports for the following equity managers: AJO, Artisan, Mondrian Emerging, Mondrian International, PIMCO Stocks Plus, Research Affiliates and T. -

UNLOCKING OPPORTUNITIES for WOMEN and BUSINESS a Toolkit of Actions and Strategies for Oil, Gas, and Mining Companies

UNLOCKING OPPORTUNITIES FOR WOMEN AND BUSINESS A Toolkit of Actions and Strategies for Oil, Gas, and Mining Companies INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IFC 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 U.S.A. ifc.org IFC—a sister organization of the World Bank and member of the World Bank Group—is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging markets. We work with more than 2,000 businesses worldwide, using our capital, expertise, and influence to create markets and opportunities in the toughest areas of the world. In FY17, we delivered a record $19.3 billion in long-term financing for developing countries, leveraging the power of the private sector to help end poverty and boost shared prosperity. For more information, visit www.ifc.org. All rights reserved The Umbrella Facility for Gender Equality (UFGE) is a World Bank Group multi-donor trust fund expanding evidence, knowledge and data needed to identify and address key gaps between men and women to deliver better development solutions that boost prosperity and increase opportunity for all. The UFGE has received generous contributions from Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and the United States. First printing, May 2018 The findings, interpretations, views, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Finance Corporation or of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the World Bank) or the governments they represent. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. -

The Gordian Knot: Apartheid & the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order, 1960-1970

THE GORDIAN KNOT: APARTHEID & THE UNMAKING OF THE LIBERAL WORLD ORDER, 1960-1970 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Ryan Irwin, B.A., M.A. History ***** The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Peter Hahn Professor Robert McMahon Professor Kevin Boyle Professor Martha van Wyk © 2010 by Ryan Irwin All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the apartheid debate from an international perspective. Positioned at the methodological intersection of intellectual and diplomatic history, it examines how, where, and why African nationalists, Afrikaner nationalists, and American liberals contested South Africa’s place in the global community in the 1960s. It uses this fight to explore the contradictions of international politics in the decade after second-wave decolonization. The apartheid debate was never at the center of global affairs in this period, but it rallied international opinions in ways that attached particular meanings to concepts of development, order, justice, and freedom. As such, the debate about South Africa provides a microcosm of the larger postcolonial moment, exposing the deep-seated differences between politicians and policymakers in the First and Third Worlds, as well as the paradoxical nature of change in the late twentieth century. This dissertation tells three interlocking stories. First, it charts the rise and fall of African nationalism. For a brief yet important moment in the early and mid-1960s, African nationalists felt genuinely that they could remake global norms in Africa’s image and abolish the ideology of white supremacy through U.N. -

Redakteursbrief

Kortpad na advertensies 25 Desember 2016 Algemene nuusbrokkies Gemeenskapsadvertensies Kleinadvertensies (Persoonlik) Kleinadvertensies (Besigheid) Geestelike Pitkos Werksgeleenthede Afrikaanse kerkdienste Landswye dagboek Riglyne vir adverteerders Kanselleer intekening / Unsubscribe Redakteursbrief Om praktiese redes aan die einde van ‘n baie besige jaar vir my, gebruik ek heelwat van dieselfde inligting wat in hierdie week se Kiwi-Brokkies verskyn ook hier weens die generiese aard daarvan. Dit was ‘n geskiedkundige jaar in die sin dat Aus-Brokkies ewe beskeie uit Nieu-Seeland se BROKKIES (wat toe reeds vir 15 jaar lank bestaan het) gebore is. So het die twee susterspublikasies ontstaan: Aus-Brokkies en Kiwi-Brokkies. Dit was die verwesenliking van ‘n droom vir my. Ons het nou ook vir die soveelste keer die voorreg om Kersfees te vier, en spesifiek die herdenking van die geboorte van ons Verlosser Jesus Christus, die Goeie Nuus wat soveel eeue lank deur profete voorspel is. Baie mense in hierdie deurmekaar wêreld erken Homs slegs as mens. Hulle is ten minste eerlik oor die emmers vol historiese getuienis (ook buite-Bybels) dat Hy wel bestaan het. Hulle het egter vir hulself ‘n versperring opgerig by die kwessie of Hy wel die dood oorwin het en of Hy God in mensgestalte was. As Jesus nie na sy Kruisdood opgestaan het nie, was hy slegs ‘n goeie mens. Indien Hy egter wel uit die dood opgestaan het, verdien dit dieper besinning – vir ons eie siel se onthalwe. Uit sy Woord leer ons dat Hy elke persoon geskep het met ‘n diepliggende kennis van Hom. Hy sê elke mens weet dat God bestaan, hoewel dit dikwels ten sterkste deur mense betwis word. -

THE UNITED STATES and SOUTH AFRICA in the NIXON YEARS by Eric J. Morgan This Thesis Examines Relat

ABSTRACT THE SIN OF OMISSION: THE UNITED STATES AND SOUTH AFRICA IN THE NIXON YEARS by Eric J. Morgan This thesis examines relations between the United States and South Africa during Richard Nixon’s first presidential administration. While South Africa was not crucial to Nixon’s foreign policy, the racially-divided nation offered the United States a stabile economic partner and ally against communism on the otherwise chaotic post-colonial African continent. Nixon strengthened relations with the white minority government by quietly lifting sanctions, increasing economic and cultural ties, and improving communications between Washington and Pretoria. However, while Nixon’s policy was shortsighted and hypocritical, the Afrikaner government remained suspicious, believing that the Nixon administration continued to interfere in South Africa’s domestic affairs despite its new policy relaxations. The Nixon administration concluded that change in South Africa could only be achieved through the Afrikaner government, and therefore ignored black South Africans. Nixon’s indifference strengthened apartheid and hindered liberation efforts, helping to delay black South African freedom for nearly two decades beyond his presidency. THE SIN OF OMMISSION: THE UNITED STATES AND SOUTH AFRICA IN THE NIXON YEARS A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Eric J. Morgan Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2003 Advisor __________________________________ (Dr. Jeffrey P. Kimball) Reader ___________________________________ (Dr. Allan M. Winkler) Reader ___________________________________ (Dr. Osaak Olumwullah) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements . iii Prologue The Wonderful Tar Baby Story . 1 Chapter One The Unmovable Monolith . 3 Chapter Two Foresight and Folly . -

Produksie Notas

- 1 - - 2 - INLEIDING Die oorspronklike konsep van 'Liefling die Movie' is geformuleer deur Paul Kruger in 2008. Voor- produksie het in 2009 begin en die rolprent sal hierdie somer op 19 November in Suid Afrika vrygestel word. Dit is n eerste vir Suid Afrika op verskeie gebiede. Die eerste Afrikaanse musiekblyspel wat in 30 jaar op die groot skerm vertoon sal word. Die room van Suid Afrikaanse produksie spanne, kunstenaars en akteurs is betrek. Die film is binne drie maande in en om Hartbeespoortdam in Noordwes geskiet. Die film is vervaardig onder die vaandel van Hartiwood Films met Paul Kruger as die leier en fotografiese regisseur van die Liefling-span. 24 Afrikaanse liedjies is verwerk deur Johan Heystek en die choreograaf is Raymond Theart. Brian Webber is die regisseur van die opwindende dans en sangervaring in 'Liefling, die Movie' LIGGING Liefling, die Movie is hoofsaaklik in die dorpie Hartbeespoort in die Noordwes Provinsie geskiet. Die dorp is om die Hartbeespoortdam gebou. Dit is geleë suid van die Magaliesberge en noord van die Witwatersberge, ongeveer 35km wes van Pretoria. Die panoramiese uitsig en bergagtige ligging het meegebring dat Hartbeespoort n gewilde uitspanplek vir stedelinge geword het.Dit bied n verskeidenheid van water- en lugsport aan besoekers, spog ook met n akwarium, private dieretuin, slangpark,en kabelspoor. Die pragtige natuurskoon is n perfekte agtergrond vir rolprent. - 3 - LIEFLING – DIE LIEDJIE - LIRIEKE Jy weet dat ek nie sonder jou kan bestaan nie Jy weet dat jy ook nie alleen kan bestaan nie Dit -

A Teachers Guide to Accompany the Slide Show

A Teachers Guide to Accompany the Slide Show by Kevin Danaher A Teachers Guide to Accompany the Slide Show by Kevin Danaher @ 1982 The Washington Office on Africa Educational Fund Contents Introduction .................................................1 Chapter One The Imprisoned Society: An Overview ..................... 5 South Africa: Land of inequality ............................... 5 1. bantustans ................................................6 2. influx Control ..............................................9 3. Pass Laws .................................................9 4. Government Represskn ....................................8 Chapter Two The Soweto Rebellion and Apartheid Schooling ......... 12 Chapter Three Early History ...............................................15 The Cape Colony: European Settlers Encounter African Societies in the 17th Century ................ 15 The European Conquest of Sotho and Nguni Land ............. 17 The Birth d ANC Opens a New Era ........................... 20 Industrialization. ............................................ 20 Foundations of Apartheid .................................... 21 Chapter Four South Africa Since WurJd War II .......................... 24 Constructing Apcrrtheid ........................... J .......... 25 Thd Afriqn National Congress of South Africa ................. 27 The Freedom Chafler ........................................ 29 The Treason Trid ........................................... 33 The Pan Africanht Congress ................................. 34 The -

Afrikaner Values in Post-Apartheid South Africa: an Anthropological Perspective

AFRIKANER VALUES IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE WRITTEN BY: JAN PETRUS VAN DER MERWE NOVEMBER 2009 ii AFRIKANER VALUES IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE BY JAN PETRUS VAN DER MERWE STUDENT NUMBER: 2005076118 This thesis/dissertation was submitted in accordance with the conditions and requirements for the degree of: Ph.D. in the Faculty of the Humanities Department of Anthropology University of the Free State Bloemfontein Supervisor: Prof. P.A. Erasmus Department of Anthropology University of the Free State Bloemfontein iii DECLARATION I, Jan Petrus van der Merwe, herewith declare that this thesis, which was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements pertaining to my doctorate in Anthropology at the University of the Free State, is my own independent work. Furthermore, I declare that this thesis has never been submitted at any other university or tertiary training centre for academic consideration. In addition, I hereby cede all copyright in respect of my doctoral thesis to the University of the Free State. .............................................................. ................................... JAN PETRUS VAN DER MERWE DATUM iv INDEX DESCRIPTION PAGE PREAMBLE 1 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 Problem statement and objectives 5 1.2 Clarification of concepts 7 1.2.1 Values as an aspect of culture 7 1.2.2 Values as identity 11 1.2.3 Values as narrative 14 1.2.4 Religion values as part of Afrikaner identity 16 1.2.5 Values as morality 17 1.2.6 Culture and identification -

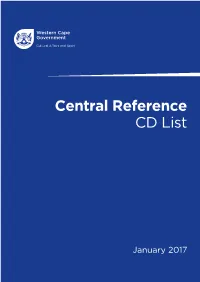

Central Reference CD List

Central Reference CD List January 2017 AUTHOR TITLE McDermott, Lydia Afrikaans Mandela, Nelson, 1918-2013 Nelson Mandela’s favorite African folktales Warnasch, Christopher Easy English [basic English for speakers of all languages] Easy English vocabulary Raifsnider, Barbara Fluent English Williams, Steve Basic German Goulding, Sylvia 15-minute German learn German in just 15 minutes a day Martin, Sigrid-B German [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Dutch in 60 minutes Dutch [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Swedish in 60 minutes Berlitz Danish in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian in 60 minutes Berlitz Norwegian phrase book & CD McNab, Rosi Basic French Lemoine, Caroline 15-minute French learn French in just 15 minutes a day Campbell, Harry Speak French Di Stefano, Anna Basic Italian Logi, Francesca 15-minute Italian learn Italian in just 15 minutes a day Cisneros, Isabel Latin-American Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Latin American Spanish in 60 minutes Martin, Rosa Maria Basic Spanish Cisneros, Isabel Spanish [beginner’s CD language course] Spanish for travelers Spanish for travelers Campbell, Harry Speak Spanish Allen, Maria Fernanda S. Portuguese [beginner’s CD language course] Berlitz Portuguese in 60 minutes Sharpley, G.D.A. Beginner’s Latin Economides, Athena Collins easy learning Greek Garoufalia, Hara Greek conversation Berlitz Greek in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi in 60 minutes Berlitz Hindi travel pack Bhatt, Sunil Kumar Hindi : a complete course for beginners Pendar, Nick Farsi : a complete course for beginners -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

Afrikaans Huistaal Voor Te Berei

AFRIKAANS HUISTAAL Graad 12 HERSIENINGSGIDS INHOUDSOPGAWE BLADSY 1. Voorwoord 3 2. Hoe om hierdie Hersieningsgids te gebruik 4 3. Hersieningsnotas en –aktiwiteite 5 Tipiese eksamenvrae 5 Leesbegrip, opsomming, taalstrukture en -konvensies: Vraestel 1 8 Die beantwoording van die leesbegripsvraag 9 Die beantwoording van die opsomming 12 Fokuspunte vir taalstrukture en –konvensies 15 Jou taalkurrikulum 21 Oefeninge: taalstrukture en –konvensies 32 Voorbeeldvraestel 1 en memorandum 39 Letterkunde: Vraestel 2 61 Literêre aspekte/kenmerke van poësie 69 Werkkaart om vir poësie voor te berei 78 Oefening: Gedig 79 Wenke vir die benadering van die roman en drama 81 Voorbeeld van ’n literêre opstel 84 Skryf: Vraestel 3 85 Oefeninge: Vraestel 3 117 4. Studiewenke 121 5. Boodskap van die samestellers 122 Bronnelys 123 2 1. Voorwoord Boodskap van die Minister van Basiese Onderwys aan die Graad 12-leerders wat ʼn tweede geleentheid gegun word “Matric” (Grade12) is perhaps the most important examination you will prepare for. It is the gateway to your future; it is the means to enter tertiary institutions; it is your opportunity to create the career of your dreams. It is not easy to accomplish but it can be done with hard work and dedication; with prioritising your time and effort to ensure that you cover as much content as possible in order to be well prepared for the examinations. I cannot stress the importance and value of revision in preparing for the examinations. Once you have covered all the content and topics, you should start working through the past examination papers; thereafter check your answers with the memoranda.