Concerning Sir Gilbert Hay, the Authorship of Alexander the Conquerour and the Buik of Alexander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing)

Programme MONDAY 30 JUNE 10.00-11.00 Plenary: Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing) 11.00-11.30 Coffee 11.30-1.00 Session 1 A) Narrating the Nation: Historiography and Identity in Stewart Scotland (c.1440- 1540): a) „Dream and Vision in the Scotichronicon‟, Kylie Murray, Lincoln College, Oxford. b) „Imagined Histories: Memory and Nation in Hary‟s Wallace‟, Kate Ash, University of Manchester. c) „The Politics of Translation in Bellenden‟s Chronicle of Scotland‟, Ryoko Harikae, St Hilda‟s College, Oxford. B) Script to Print: a) „George Buchanan‟s De jure regni apud Scotos: from Script to Print…‟, Carine Ferradou, University of Aix-en-Provence. b) „To expone strange histories and termis wild‟: the glossing of Douglas‟s Eneados in manuscript and print‟, Jane Griffiths, University of Bristol. c) „Poetry of Alexander Craig of Rosecraig‟, Michael Spiller, University of Aberdeen. 1.00-2.00 Lunch 2.00-3.30 Session 2 A) Gavin Douglas: a) „„Throw owt the ile yclepit Albyon‟ and beyond: tradition and rewriting Gavin Douglas‟, Valentina Bricchi, b) „„The wild fury of Turnus, now lyis slayn‟: Chivalry and Alienation in Gavin Douglas‟ Eneados‟, Anna Caughey, Christ Church College, Oxford. c) „Rereading the „cleaned‟ „Aeneid‟: Gavin Douglas‟ „dirty‟ „Eneados‟, Tom Rutledge, University of East Anglia. B) National Borders: a) „Shades of the East: “Orientalism” and/as Religious Regional “Nationalism” in The Buke of the Howlat and The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy‟, Iain Macleod Higgins, University of Victoria . b) „The „theivis of Liddisdaill‟ and the patriotic hero: contrasting perceptions of the „wickit‟ Borderers in late medieval poetry and ballads‟, Anna Groundwater, University of Edinburgh 1 c) „The Literary Contexts of „Scotish Field‟, Thorlac Turville-Petre, University of Nottingham. -

Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten MacGregor, Martin (2009) Gaelic barbarity and Scottish identity in the later Middle Ages. In: Broun, Dauvit and MacGregor, Martin(eds.) Mìorun mòr nan Gall, 'The great ill-will of the Lowlander'? Lowland perceptions of the Highlands, medieval and modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, pp. 7-48. ISBN 978085261820X Copyright © 2009 University of Glasgow A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91508/ Deposited on: 24 February 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages MARTIN MACGREGOR One point of reasonably clear consensus among Scottish historians during the twentieth century was that a ‘Highland/Lowland divide’ came into being in the second half of the fourteenth century. The terminus post quem and lynchpin of their evidence was the following passage from the beginning of Book II chapter 9 in John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, which they dated variously from the 1360s to the 1390s:1 The character of the Scots however varies according to the difference in language. For they have two languages, namely the Scottish language (lingua Scotica) and the Teutonic language (lingua Theutonica). -

Scottish Language and Literatur, Medieval and Renaissance

5 CONTENTS PREFACE 9 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 13 LANGUAGE The Concise Scots Dictionary by Mairi Robinson 19 The Pronunciation Entries for the CSD by Adam J. Aitken 35 Names Reduced to Words?: Purpose and Scope of a Dictionary of Scottish Place Names by Wilhelm F. H. Nicolaisen 47 Interlingual Communication Dutch-Frisian, a Model for Scotland? by Antonia Feitsma 55 Interscandinavian Communication - a Model for Scotland? by Kurt Braunmüller 63 Interlingual Communication: Danger and Chance for the Smaller Tongues by Heinz Kloss 73 The Scots-English Round-Table Discussion "Scots: Its Development and Present Conditions - Potential Modes of its Future" - Introductory Remarks - by Dietrich Strauss 79 The Scots-English Round-Table Discussion "Scots: Its Development and Present Conditions - Potential Modes of its Future" - Synopsis - by J. Derrick McClure 85 The Scots-English Round-Table Discussion "Scots: Its Development and Present Conditions - Potential Modes of its Future" - Three Scots Contributions - by Matthew P. McDiarmid, Thomas Crawford, J. Derrick McClure 93 Open Letter from the Fourth International Conference on Scottish Language and Literature - Medieval and Renaissance 101 What Happened to Old French /ai/ in Britain? by Veronika Kniezsa 103 6 Changes in the Structure of the English Verb System: Evidence from Scots by Hubert Gburek 115 The Scottish Language from the 16th to the 18th Century: Elphinston's Works as a Mirror of Anglicisation by Clausdirk Pollner and Helmut Rohlfing 125 LITERATURE Traces of Nationalism in Eordun's Chronicle by Hans Utz 139 Some Political Aspects of The Complaynt of Scotland by Alasdair M. Stewart 151 A Prose Satire of the Sixteenth Century: George Buchanan's Chamaeleon by John W. -

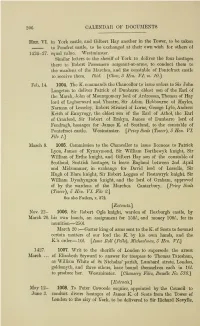

1427 to 1453

206 CALENDAE OF DOCUMENTS Hen. VI. in York castle, and Gilbert Hay another in the Tower, to be taken to Pomfret castle, to be exchanged at their own wish for others of 1426-27. equal value. Westminster. Similar letters to the sheriff of York to deliver the four hostages there to Eobert Passemere sergeant-at-arms, to conduct them to the wardens of the Marches, and the constable of Pontefract castle to receive them. IMd. {^Closc, 5 Hen. VI. m. JO.] Feb. 14. 1004. The K. commands the Chancellor to issue orders to Sir John Langeton to deliver Patrick of Dunbarre eldest son of the Earl of the March, John of Mountgomery lord of Ardrossan, Thomas of Hay lord of Loghorward and Yhestre, Sir Adam Hebbourne of Hayles, Norman of Lesseley, Eobert Stiward of Lome, George Lyle, Andrew Keith of Ennyrugy, the eldest son of the Earl of Athol, the Earl of Crauford, Sir Eobert of Erskyn, James of Dunbarre lord of Fendragh, hostages for James K. of Scotland, to the constable of Pontefract castle. Westminster. {^Privy Seals (Toiuer), 5 Hen. VI. File I] March 8. 1005. Commission to the Chancellor to issue licences to Patrick Lyon, James of Kynnymond, Sir William Borthewyk knight, Sir William of Erthe knight, and Gilbert Hay son of the constable of Scotland, Scottish hostages, to leave England between 2nd April and Midsummer, in exchange for David lord of Lesselle, Sir Hugh of Blare knight. Sir Eobert Loggan of Eestawryk knight, Sir William Dysshyngton knight, and the lord of Graham, approved of by the wardens of the Marches. -

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series Skeat, W.W. ed., The kingis quiar: together with A ballad of good counsel: by King James I of Scotland, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 1 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 2 (1883) Gregor, W. ed., Ane treatise callit The court of Venus, deuidit into four buikis. Newlie compylit be Iohne Rolland in Dalkeith, 1575, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 3 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 4 (1893) Cody, E.G. ed., The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, Bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, religious in the Scottis Cloister of Regensburg, the zeare of God, 1596. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 5 (1888) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 6 (1889) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 7 (1889) McNeill, G.P. ed., Sir Tristrem, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 8 (1886) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 9 (1887) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. -

Gavin Douglas's Aeneados: Caxton's English and 'Our Scottis Langage' Jacquelyn Hendricks Santa Clara University

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 43 | Issue 2 Article 21 12-15-2017 Gavin Douglas's Aeneados: Caxton's English and 'Our Scottis Langage' Jacquelyn Hendricks Santa Clara University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Hendricks, Jacquelyn (2017) "Gavin Douglas's Aeneados: Caxton's English and 'Our Scottis Langage'," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 43: Iss. 2, 220–236. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol43/iss2/21 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GAVIN DOUGLAS’S AENEADOS: CAXTON’S ENGLISH AND "OUR SCOTTIS LANGAGE" Jacquelyn Hendricks In his 1513 translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, titled Eneados, Gavin Douglas begins with a prologue in which he explicitly attacks William Caxton’s 1490 Eneydos. Douglas exclaims that Caxton’s work has “na thing ado” with Virgil’s poem, but rather Caxton “schamefully that story dyd pervert” (I Prologue 142-145).1 Many scholars have discussed Douglas’s reaction to Caxton via the text’s relationship to the rapidly spreading humanist movement and its significance as the first vernacular version of Virgil’s celebrated epic available to Scottish and English readers that was translated directly from the original Latin.2 This attack on Caxton has been viewed by 1 All Gavin Douglas quotations and parentheical citations (section and line number) are from D.F.C. -

Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 12 2007 Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth- Century Scottish Literature Sally Mapstone St. Hilda's College, Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mapstone, Sally (2007) "Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 131–155. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sally Mapstone Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature Among the voluminous papers of William Drummond of Hawthomden, not, however with the majority of them in the National Library of Scotland, but in a manuscript identified about thirty years ago and presently in Dundee Uni versity Library, 1 is a small and succinct record kept by the author of significant events and moments in his life; it is entitled "MEMORIALLS." One aspect of this record puzzled Drummond's bibliographer and editor, R. H. MacDonald. This was Drummond's idiosyncratic use of the term "fatall." Drummond first employs this in the "Memorialls" to describe something that happened when he was twenty-five: "Tusday the 21 of Agust [sic] 1610 about Noone by the Death of my father began to be fatall to mee the 25 of my age" (Poems, p. -

245X ANGUS Mcintosh LECTURE 7 January, 2008

1 ISSN 2046-245X ANGUS McINTOSH LECTURE 7 January, 2008 2 ‘Revisiting the makars’ Angus McIntosh was, as you have heard, president of the Scottish Text Society for twelve years from 1977 to 1989, and honorary president thereafter. Although of Scots parentage, as you can tell from his name, he wasn’t a Scot but was born, as he used to say, in the old kingdom of Deira, south of the Tyne, or perhaps Bernicia, depending on where you think the boundary lay. The Society was extraordinarily lucky to secure the services of such an immensely distinguished scholar. As Forbes Professor of English Language here at Edinburgh, he led what was surely the greatest department of English language in the world. 1986 saw the publication of the four-volume Linguistic Atlas of Later Medieval English, the huge project which he had masterminded since its inception in 1952. During his years as President of the STS he was also working tirelessly to sustain the Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue as chair of its Joint Council, a position he held for thirty years. The Scottish Text Society in the late seventies and eighties, when Angus was president, had an eminent Council, which included among others Jack Aitken, who was the backbone of the Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue, and his successor, Jim Stevenson; Tom Crawford and Matthew McDiarmid, from Aberdeen; David Daiches, Ronnie Jack, Emily Lyle and Jack MacQueen from Edinburgh; Rod Lyall and Alex Scott from Glasgow. Those were the days when 3 the teaching of older Scots literature and language flourished in the Scottish universities. -

Middle Scots Bibliography: Problems and Perspectives Walter Scheps

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 26 | Issue 1 Article 20 1991 Middle Scots Bibliography: Problems and Perspectives Walter Scheps Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Scheps, Walter (1991) "Middle Scots Bibliography: Problems and Perspectives," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 26: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol26/iss1/20 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walter Scheps Middle Scots Bibliography: Problems and Perspectives It is axiomatic that criticism changes literature; it should be equally axiomatic that bibliography changes criticism. Questions of scope, evalua tion vs. description, and the like must be addressed by every bibliographer regardless of subject. Middle Scots bibliography presents all of the problems common to bibliography generally, but, in addition, it contains several which are uniquely its own, the result of cultural and historica1 factors of long duration. Finally, innovations in technology, word processing in particular, have changed the ways in which bibliographies are compiled and produced, and may ultimately change the ways in which they are conceived as well. It is with these issues that this paper is concerned. The ftrst question confronting any bibliographer is the scope of his study. The second is whether his bibliography is to be descriptive or eval uative. These issues seem to be straight-forward enough, but, here as else where, appearances are deceptive. -

First Series, 1883-1910 1 the Kingis Quair, Ed. W. W. Skeat 1884 2 The

First Series, 1883-1910 1 The Kingis Quair, ed. W. W. Skeat 1884 2 The Poems of William Dunbar I, ed. John Small 1893 3 The Court of Venus, by John Rolland. 1575, ed. Walter Gregor 1884 4 The Poems of William Dunbar II, ed. John Small 1893 5 Leslie’s Historie of Scotland I, ed. E.G. Cody 1888 6 Schir William Wallace I, ed. James Moir 1889 7 Schir William Wallace II, ed. James Moir 1889 8 Sir Tristrem, ed. G.P. McNeill 1886 9 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie I, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 10 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie II, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 11 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie III, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 12 The Richt Vay to the Kingdome of Heuine by John Gau, ed. A.F. Mitchell 1888 13 Legends of the Saints I, ed. W.M. Metcalfe 1887 14 Leslie’s History of Scotland II, ed. E.G. Cody 1895 15 Niniane Winzet’s Works I, ed. J. King Hewison 1888 16 The Poems of William Dunbar III, ed. John Small, Introduction by Æ.J.G. Mackay 1893 17 Schir William Wallace III, ed. James Moir 1889 18 Legends of the Saints II, ed. W.M. Metcalfe 1888 19 Leslie’s History of Scotland III, ed. E.G. Cody 1895 20 Satirical Poems of the Time of the Reformation I, ed. James Cranstoun REPRINT 1889 21 The Poems of William Dunbar IV, ed. John Small 1893 22 Niniane Winzet’s Works II, ed. J. King Hewison 1890 23 Legends of the Saints III, ed. -

Makar's Court

Culture and Sport Committee 2.00pm, Monday, 20 March 2017 Makars’ Court: Proposed Additional Inscriptions Item number Report number Executive/routine Wards All Executive Summary Makars’ Court at the Writers’ Museum celebrates the achievements of Scottish writers. This ongoing project to create a Scottish equivalent of Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey was the initiative of the former Culture and Leisure Department, in association with the Saltire Society and Lothian and Edinburgh Enterprise Ltd, as it was then known. It was always the intention that Makars’ Court would grow and develop into a Scottish national literary monument as more writers were commemorated. At its meeting on 10 March 1997 the then Recreation Committee established that the method of selecting writers for commemoration would involve the Writers’ Museum forwarding sponsorship requests for commemorating writers to the Saltire Society, who would in turn make a recommendation to the Council. The Council of the Saltire Society now recommends that two further applications be approved, to commemorate William Soutar (1898-1943) – poet and diarist, and George Campbell Hay (1915-1984) – poet. Links Coalition Pledges P31 Council Priorities CP6 Single Outcome Agreement SO2 Report Makar’s Court: Proposed Additional Inscriptions 1. Recommendations 1.1 It is recommended that the Committee approves the addition of the proposed new inscriptions to Makars’ Court. 2. Background 2.1 Makars’ Court at the Writers’ Museum celebrates the achievements of Scottish writers. This ongoing project to create a Scottish equivalent of Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey was the initiative of the former Culture and Leisure Department, in association with the Saltire Society and Lothian and Edinburgh Enterprise Ltd, as it was then known. -

Download Download

CONTENTS OF APPENDIX. Page I. List of Members of the Society from 1831 to 1851:— I. List of Fellows of the Society,.................................................. 1 II. List of Honorary Members....................................................... 8 III. List of Corresponding Members, ............................................. 9 II. List of Communications read at Meetings of the Society, from 1831 to 1851,............................................................... 13 III. Listofthe Office-Bearers from 1831 to 1851,........................... 51 IV. Index to the Names of Donors............................................... 53 V. Index to the Names of Literary Contributors............................. 59 I. LISTS OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF THE ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. MDCCCXXXL—MDCCCLI. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN, PATRON. No. I.—LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. (Continued from the AppenHix to Vol. III. p. 15.) 1831. Jan. 24. ALEXANDER LOGAN, Esq., London. Feb. 14. JOHN STEWARD WOOD, Esq. 28. JAMES NAIRWE of Claremont, Esq., Writer to the Signet. Mar. 14. ONESEPHORUS TYNDAL BRUCE of Falkland, Esq. WILLIAM SMITH, Esq., late Lord Provost of Glasgow. Rev. JAMES CHAPMAN, Chaplain, Edinburgh Castle. April 11. ALEXANDER WELLESLEY LEITH, Esq., Advocate.1 WILLIAM DAUNEY, Esq., Advocate. JOHN ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL, Esq., Writer to the Signet. May 23. THOMAS HOG, Esq.2 1832. Jan. 9. BINDON BLOOD of Cranachar, Esq., Ireland. JOHN BLACK GRACIE, Esq.. Writer to the Signet. 23. Rev. JOHN REID OMOND, Minister of Monfcie. Feb. 27. THOMAS HAMILTON, Esq., Rydal. Mar. 12. GEORGE RITCHIE KINLOCH, Esq.3 26. ANDREW DUN, Esq., Writer to the Signet. April 9. JAMES USHER, Esq., Writer to the Signet.* May 21. WILLIAM MAULE, Esq. 1 Afterwards Sir Alexander W. Leith, Bart. " 4 Election cancelled. 3 Resigned. VOL. IV.—APP. A 2 LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY.