On My Journey Through the Sino-German Literary Interflow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Fukan As a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light

Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences Volume 20 Issue 1 Article 6 2017 Building Fukan as a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light Nuan Gao Hanover College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jiass Recommended Citation Gao, Nuan (2017) "Building Fukan as a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light," Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jiass/vol20/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Building Fukan as a Chinese Public Sphere: Zhang Dongsun and Learning Light* NUAN GAO Hanover College ABSTRACT This article attempts to explore the relevance of the public sphere, conceptualized by Jürgen Habermas, in the Chinese context. The author focuses on the case of Learning Light (Xuedeng), one of the most reputable fukans, or newspaper supplements, of the May Fourth era (1915–1926), arguing that fukan served a very Habermasian function, in terms of its independence from power intervention and its inclusiveness of incorporating voices across political and social strata. Through examining the leadership of Zhang Dongsun, editor in chief of Learning Light, as well as the public opinions published in this fukan, the author also discovers that, in constructing China’s public sphere, both the left and moderate intellectuals of the May Fourth era used conscious effort and shared the same moral courage, although their roles were quite different: The left was more prominent as passionate and idealist spiritual leaders shining in the center of the historic stage, whereas in comparison, the moderates acted as pragmatic and rational organizers, ensuring a benevolent environment for the stage. -

History of China and Japan from 1900To 1976 Ad 18Bhi63c

HISTORY OF CHINA AND JAPAN FROM 1900TO 1976 A.D 18BHI63C (UNIT II) V.VIJAYAKUMAR 9025570709 III B A HISTORY - VI SEMESTER Yuan Shikai Yuan Shikai (Chinese: 袁世凱; pinyin: Yuán Shìkǎi; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty, becoming the Emperor of the Empire of China (1915–1916). He tried to save the dynasty with a number of modernization projects including bureaucratic, fiscal, judicial, educational, and other reforms, despite playing a key part in the failure of the Hundred Days' Reform. He established the first modern army and a more efficient provincial government in North China in the last years of the Qing dynasty before the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor, the last monarch of the Qing dynasty, in 1912. Through negotiation, he became the first President of the Republic of China in 1912.[1] This army and bureaucratic control were the foundation of his autocratic. He was frustrated in a short-lived attempt to restore hereditary monarchy in China, with himself as the Hongxian Emperor (Chinese: 洪憲皇帝). His death shortly after his abdication led to the fragmentation of the Chinese political system and the end of the Beiyang government as China's central authority. On 16 September 1859, Yuan was born as Yuan Shikai in the village of Zhangying (張營村), Xiangcheng County, Chenzhou Prefecture, Henan, China. The Yuan clan later moved 16 kilometers southeast of Xiangcheng to a hilly area that was easier to defend against bandits. There the Yuans had built a fortified village, Yuanzhaicun (Chinese: 袁寨村; lit. -

The Ethnicities of Philosophy and the Limits of Culture

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1998 The ethnicities of philosophy and the limits of culture. Joseph S. Yeh University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Yeh, Joseph S., "The ethnicities of philosophy and the limits of culture." (1998). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2310. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2310 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETHNICITIES OF PHILOSOPHY AND THE LIMITS OF CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by Joseph S. Yeh Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 1998 Department of Philosophy © Copyright by Joseph Steven Yeh 1998 All Rights Reserved THE ETHNICITIES OF PHILOSOPHY AND THE LIMITS OF CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by Joseph S. Yeh Approved as to style and content by: Robert John Ackermann, Chair & Ann Ferguson, Member i Robert Paul Wolff Member Lucy Nga[yen. Member Johr^Robison, Head Department of Philosophy ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my family, who have given the me most unqualified and unswerving support. I owe a debt of tremendous proportions. My brother and fiiture neurosurgeon/pilot. David John Yeh. was kind enough to grant me the use of the space and technology required for a work this of scope. -

Philosoph, Konfuzianismus, Dichter, Historiker Bibliographie : Autor 1878 Andreozzi, Alfonso

Report Title - p. 1 of 266 Report Title Ban, Gu (Anling = Xingping, Shaanxi 32-92) : Philosoph, Konfuzianismus, Dichter, Historiker Bibliographie : Autor 1878 Andreozzi, Alfonso. Le leggi penali degli antichi Cinesi : discorso proemiale sul diritto e sui limiti del punire. Traduzioni originali dal cinese, dell'avvocato Alfonso Andreozzi. (Firenze : G. Civelli, 1878). [Ban, Gu. Han shu] [WC] 1931 Bai hu tong yin de = Index to Pai hu t’ung. Hong Ye [William Hung et al.]. (Peking : Yenching University, 1931). (Yin de ; 2 = Harvard-Yenching Institute sinological index series ; 2). [Ban, Gu. Bai hu tong]. 1939 Pan, Ku. Die Monographie über Wang Mang : (Ts'ien-Han-shu, Kap. 99). Kritisch bearbeitet, übersetzt und erklärt von Hans O.H. Stange. (Leipzig : F.A. Brockhaus, 1939). (Abhandlungen für die Kunde des Morgenlandes ; Bd. 23, Nr. 3). Habil. Univ. Berlin, 1939. Übersetzung von Ban, Gu. Han shu. 1949-1952 Tjan, Tjoe Som. Po hu t'ung : the comprehensive discussions in the White Tiger Hall : contribution to the history of classical studies in the Han period. (Leiden : E.J. Brill, 1949-1952). (Sinica Leidensia ; vol. 6). Diss. Univ. Leiden, 1938. [Ban, Gu. Bai hu tong. ]. 1955 Pan, Ku. The history of the former Han dynasty. A critical translation, with annotations, by Homer H. Dubs ; with the collab. of Jen T'ai and P'an Lo-chi. Vol. 1-3. (Baltimore, Waverly Press, 1938-1955). [Ban, Gu. Qian Han shu ; Ren Tai ; Pan Luoji]. 1960 Hughes, E[rnest] R[ichard]. Two Chinese poets : vignettes of Han life and thought. (Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1960). [Enthält Texte von Ban Gu ; Zhang Heng]. -

“Ceaseless Generation”: Republican China's Rediscovery And

vitalism in republican china Asia Major (2017) 3d ser. Vol. 30.2: 101-31 ku-ming (kevin) chang “Ceaseless Generation”: Republican China’s Rediscovery and Expansion of Domestic Vitalism abstract: After the arrival of the vitalist philosophy of Henri Bergson and Hans Driesch in the 1910s, Chinese intellectuals formulated and expanded a domestic version of vital- ism that located its origin in such classical passages as “repeated generation of life constitutes change 生生之謂易” from the Book of Changes. Liang Shuming 梁漱溟 first formulated this domestic vitalism, which mirrored Bergson’s philosophy of change, flow, and life. Zhu Qianzhi 朱謙之, Li Shicen 李石岑, Xiong Shili 熊十力, and Fang Dongmei 方東美 expanded the idea in the context of their responses to new cultural, intellectual and geopolitical realities. This article surveys the trajectory of this domes- tic Chinese vitalism in the first half of the twentieth century and elucidates its im- portance as a curious combination of conservative and liberal, Eastern and Western, traditional and modern thinking. keywords: vitalism, Henri Bergson, Hans Driesch, New Confucians, Yogƒcƒra Buddhism (weishi 唯 識), Republican China ooted in Western antiquity, vitalism is a school of thought that R postulates a source, or cause, of life. It was transformed in late- seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe into a medical theory and a philosophical position. In it, the working of the living body followed a principle — often known as the vital principle or vital force — that was distinct from the mechanical laws underlying the chemistry and phys- ics at work in nonliving bodies.1 Vitalism enjoyed some popularity in the early-twentieth century, largely thanks to the French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859–1941) and the German biologist and philosopher Hans Driesch (1867–1941). -

Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Zhong Yurou

Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Zhong Yurou Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Yurou Zhong All rights reserved ABSTRACT Script Crisis and Literary Modernity in China, 1916-1958 Yurou Zhong This dissertation examines the modern Chinese script crisis in twentieth-century China. It situates the Chinese script crisis within the modern phenomenon of phonocentrism – the systematic privileging of speech over writing. It depicts the Chinese experience as an integral part of a worldwide crisis of non-alphabetic scripts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It places the crisis of Chinese characters at the center of the making of modern Chinese language, literature, and culture. It investigates how the script crisis and the ensuing script revolution intersect with significant historical processes such as the Chinese engagement in the two World Wars, national and international education movements, the Communist revolution, and national salvation. Since the late nineteenth century, the Chinese writing system began to be targeted as the roadblock to literacy, science and democracy. Chinese and foreign scholars took the abolition of Chinese script to be the condition of modernity. A script revolution was launched as the Chinese response to the script crisis. This dissertation traces the beginning of the crisis to 1916, when Chao Yuen Ren published his English article “The Problem of the Chinese Language,” sweeping away all theoretical oppositions to alphabetizing the Chinese script. This was followed by two major movements dedicated to the task of eradicating Chinese characters: First, the Chinese Romanization Movement spearheaded by a group of Chinese and international scholars which was quickly endorsed by the Guomingdang (GMD) Nationalist government in the 1920s; Second, the dissident Chinese Latinization Movement initiated in the Soviet Union and championed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the 1930s. -

A Prestigious Translator and Writer of Children’S Literature

A Study of Chinese Translations and Interpretations of H.C. Andersen's Tales History and Influence Li, Wenjie Publication date: 2014 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Li, W. (2014). A Study of Chinese Translations and Interpretations of H.C. Andersen's Tales: History and Influence. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 01. okt.. 2021 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN PhD thesis Li Wenjie Thesis title A STUDY OF CHINESE TRANSLATIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS OF H.C. ANDERSEN’S TALES: HISTORY AND INFLUENCE Academic advisor: Henrik Gottlieb Submitted: 23/01/2014 Institutnavn: Institut for Engelsk, Germansk and Romansk Name of department: Department of English, Germanic and Romance Studies Author: Li Wenjie Titel og evt. undertitel: En undersøgelse af kinesisk oversættelse og fortolkninger af H. C. Andersens eventyr: historie og indflydelse Title / Subtitle: A Study of Chinese Translations and Interpretations of H.C. Andersen’s Tales: History and Influence Subject description: H. C. Andersen, Tales, Translation History, Interpretation, Chinese Translation Academic advisor: Henrik Gottlieb Submitted: 23. Jan. 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. It has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Contents -

Maoist Laughter

Maoist Laughter Edited by Ping Zhu, Zhuoyi Wang, and Jason McGrath Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong https://hkupress.hku.hk © 2019 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8528-01-1 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co. Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents List of Figures vii Acknowledgments viii Introduction: The Study of Laughter in the Mao Era 1 Ping Zhu Part I: Utopian Laughter 1. Laughter, Ethnicity, and Socialist Utopia: Five Golden Flowers 19 Ban Wang 2. Revolution Plus Love in Village China: Land Reform as Political Romance in Sanliwan Village 37 Charles A. Laughlin 3. Joking after Rebellion: Performing Tibetan-Han Relations in the Chinese Military Dance “Laundry Song” (1964) 54 Emily Wilcox Part II: Intermedial Laughter 4. Intermedial Laughter: Hou Baolin and Xiangsheng Dianying in Mid-1950s China 73 Xiaoning Lu 5. Fantastic Laughter in a Socialist-Realist Tradition? The Nuances of “Satire” and “Extolment” in The Secret of the Magic Gourd and Its 1963 Film Adaptation 89 Yun Zhu 6. Humor, Vernacularization, and Intermedial Laughter in Maoist Pingtan 105 Li Guo Part III: Laughter and Language 7. Propaganda, Play, and the Pictorial Turn: Cartoon (Manhua Yuekan), 1950–1952 123 John A. -

Le Pallet Bei Nantes 1079-1142 Kloster St. Marcel, Saone) : Philosoph Biographie 1928 Ye, Lingfeng

Report Title - p. 1 of 664 Report Title Abélard, Pierre = Abaillard, Pierre = Abaelardus, Petrus (Le Pallet bei Nantes 1079-1142 Kloster St. Marcel, Saone) : Philosoph Biographie 1928 Ye, Lingfeng. Abola yu Ailüqisi de qing shu [ID D14244]. [Advertisement for Lettres d'Héloïse et d'Abailard ; transl. by Liang Shiqiu. In : Xin yue ; vol. 1, no 7 (1928). "This is a love story which happened 800 years ago. A nun and a monk have written a bundle of love letters. No love letters, whether in China or in a foreign country, are more grief-stricken, more sadly touching and more sublime than those found in this volume. The beautiful and ingenious lines have become popular quotations of lovers in later generations, showing the greatness of their influence. The most admirable point is that there is nothing frivolous in these poems, and the translator considers this anthology a 'transcendent and holy' masterpiece." [Babb23] Bibliographie : Autor 1928 [Abélard, Pierre]. Abola yu Ailüqisi de qing shu. Peter Abelard zhu ; Liang Shiqiu yi. In : Xin Yue ; vol. 1, no 8 (Oct. 10 1928). = (Shanghai : Shang wu yin shu guan, 1935). (Shi jie wen xue ming zhu). Übersetzung von Lettres d'Héloïse et d'Abailard. Ed. ornée de huit figures gravées par les meilleurs artistes de Paris, d'après les dessins et sous la direction de Moreau le jeune. Vol. 1-3. (Paris : J.B. Fournier, 1796). [Babb23] Alain = Chartier, Emile = Chartier, Emile-Auguste (Mortagne-sur-Huisne = Mortagne-au-Perche 1868-1951 Le Vésinet) : Philosoph, Schriftsteller, Journalist Bibliographie : Autor 1972 [Alain]. Xing fu lun. Chatai'er zhuan ; Zheng Jieyun zhong yi. -

The Deconstructionist Assault on China's Cultural

The Deconstructionist ren, agape¯ Assault on China’s Cultural Optimism by Michael O. Billington li, the Rites Li, Principle Xinhua/ Yao Dawei n a world economy rapidly collapsing into the worst logical optimism, finding its own way between the two depression of modern history, the role of China, the proven failures of Marxism and Adam Smith’s laissez- Iworld’s largest nation, has become a crucial factor in faire capitalism. determining the future of the world economy as a whole. China is also reaching out to other nations, both its The two dominant “systems” of the Twentieth century— Asian neighbors and beyond, with proposals for coopera- the Communist Soviet bloc and the “free enterprise” tive development of huge dimensions, which could trans- economies of the West—have followed one another into form the region into an economic engine for world devel- bankruptcy and social chaos. China, however, although opment in the next century. This fact alone explains the still suffering from a relatively underdeveloped economic hysteria in some quarters—centered in such British Intel- infrastructure and a low per-capita standard of living, is ligence thinktanks as the I.I.S.S. (the International Insti- moving forward with a visible enthusiasm and techno- tute of Strategic Studies) and their “Conservative Revolu- 26 Fireworks over Hongkong hail the city’s return to China from British colonial status, July 1, 1997. Inset left: Beijing celebrations at the countdown sign in Tiananmen Square. Inset right: Beijing University students join the celebrations. Agence France Presse/Corbis-Bettmann Xinhua/Guan Tianyi tion” allies in the U.S. -

Gu Cheng and Walt Whitman

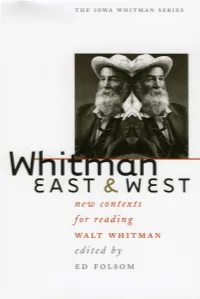

Whitman East & West the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor Whitman East & West New Contexts for Reading Walt Whitman edited by ed folsom university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2002 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America http://www.uiowa.edu/uiowapress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation. Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitman East and West: new contexts for reading Walt Whitman /edited by Ed Folsom. p. cm.—(The Iowa Whitman series) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-87745-821-9 (cloth) 1. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892— Criticism and interpretation. 2. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892— Appreciation—Asia. 3. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892— Knowledge—Asia. 4. Books and reading—Asia. 5. Asia—In literature. I. Folsom, Ed, 1947–. II. Series. ps3238 .w46 2002 811Ј.3—dc21 2002021133 02 03 04 05 06 c 54321 for robert strassburg, who has put Whitman’s words to work in his music, his teaching, and his life. His performance of his Whitman compositions in Bejing literally set the tone for the “Whitman 2000” conference. -

A Spiritual Evolutionism: Lü Cheng, Aesthetic Revolution, and the Rise of a Buddhism-Inflected Social Ontology in Modern China

Journal of Global Buddhism 2021, Vol.22 (1): 49–75 DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4727558 www.globalbuddhism.org ISSN: 1527-6457 (online) © The author(s) Research Article A Spiritual Evolutionism: Lü Cheng, Aesthetic Revolution, and the Rise of a Buddhism-Inflected Social Ontology in Modern China Jessica Xiaomin Zu University of Southern California, Dornsife This study examines the early career of the renowned Buddhologist Lü Cheng as an aspiring revolutionary. My findings reveal that Lü’s rhetoric of “aesthetic revolution” both catapulted him into the center of the New Culture Movement and popularized a Buddhist idealism—Yogācāra (consciousness-only school)—among thinkers who sought alternatives social theories. Lü aimed to refute social Darwinism and scientific materialism, which portray humans as mechanized individuals bereft of moral agency. He theorized an anti- realist social ontology, i.e., a social oneness grounded in intersubjective resonances, from which subjective interiority and objective exteriority arise. Lü turned to Buddhism to further his revolution. Buddhist soteriology supplied powerful tools for theorizing the social: The doctrine of no-self refuted philosophical solipsism and curtailed individualism; dependent-origination refashioned social evolution as collective spiritual progress. Lü’s spiritual-evolutionism-cum-social- ontology broadens the field of Buddhist philosophy that has a long-standing blind spot on social philosophies developed in the Global South. Keywords: Yogācāra; evolutionism; Buddhist soteriology; aesthetics;