Defending Air Bases in an Age of Insurgency, Vol. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delivering Security in a Changing World Future Capabilities

Delivering Security in a Changing World Future Capabilities 1 Delivering Security in a Changing World Future Capabilities Presented to Parliament by The Secretary of State for Defence By Command of Her Majesty July 2004 £7.00 Cm 6269 Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 2 Force Structure Changes 5 Chapter 3 Organisation and Efficiency 11 Chapter 4 Conclusions 13 Annex Determining the Force Structure 14 © Crown Copyright 2004 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich, NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: licensing@cabinet-office.x.gsi.gov.uk Foreword by the Secretary of State for Defence the Right Honourable Geoff Hoon MP In the Defence White Paper of last December I set out the need to defend against the principal security challenges of the future: international terrorism, the proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction, and weak and failing states. Our need in the future is for flexible and adaptable armed forces properly supported to carry out the most likely expeditionary operations. To create a more sustainable and affordable force structure which better meets these operational requirements we have secured additional resources: the 2004 Spending Review allocated £3.7 billion to defence across the Spending Review period, which represents an average real terms increase of 1.4% a year. -

United States Air Force Headquarters, 3Rd Wing Elmendorf AFB, Alaska

11 United States Air Force Headquarters, 3rd Wing Elmendorf AFB, Alaska Debris Removal Actions at LF04 Elmendorf AFB, Alaska FINAL REPORT April 10, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ............................ ................ .............................. 1 1.1 Project Objectives ............................................ 1 1.2 Scope of Work ................................................................... 1 1.3 Background Information ............................................ 1 1.3.1 Historical Investigations and Remedial Actions ........................................ 3 2 Project E xecution .................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Mobilization ..................................................................................................... 3 2.2 E quipm ent ....................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 T ransportation ................................................................................................................. 4 2.4 Ordnance Inspection ...... ........................................ 4 2.5 Debris Removal ................................................................................................... 4 2.6 Debris Transportation and Disposal ...................................... 5 2.7 Site Security .................................................................................................................... 5 2.8 Security Procedures -

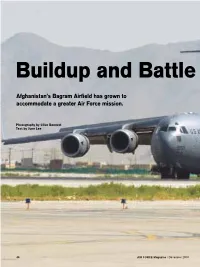

Buildup and Battle

Buildup and Battle Afghanistan’s Bagram Airfield has grown to accommodate a greater Air Force mission. Photography by Clive Bennett Text by June Lee 46 AIR FORCE Magazine / December 2010 Buildup and Battle A C-17 Globemaster III rolls to a stop on a Bagram runway after a resupply mission. Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan, has been a hotspot for NATO and US operations in Southwest Asia and there are no signs of the pace letting up. AIR FORCE Magazine / December 2010 47 n Afghanistan, Bagram Airfield Ihosts several thousand airmen and other troops, deployed from all over the world. The 455th Air Expedition- ary Wing at Bagram provides air support to coalition and NATO Inter- national Security Assistance Forces on the ground. |1| The air traffic control tower is one of the busiest places on Bagram Airfield, with more than 100 movements taking place in a day. Civilian air traffic control- lers keep an eye on the runway and the skies above Afghanistan. |2| An F-15E from the 48th Fighter Wing at RAF Lakenheath, UK, taxis past revetments for the start of another mission. All F-15s over Afghanistan fly two-ship sorties. |3| A CH-47 Chinook from the Georgia Army National Guard undergoes line main- tenance by Army Spc. Cody Staley and Spc. Joe Dominguez (in the helicopter). 1 2 3 48 AIR FORCE Magazine / December 2010 1 22 3 4 5 |1| A1C Aaron Simonson gives F-16 C-17 at Bagram wait to be unloaded. EFS, Hill AFB, Utah, and the 79th pilot Capt. Nathan Harrold the ap- These mine-resistant ambush-pro- EFS, Shaw AFB, S.C. -

Information and Questions Regarding the Army, RAF and RN

@ Defence Statistics (Tri-Service) Ministry Of Defence Main Building ~ Whitehall -.- London SW1A 2HB Ministry United Kingdom Telephone [MOD]: +44 (0)20 7807 8896 of Defence Facsimile [MOD]: +44 (0)20 7218 0969 E-mail: [email protected] Reference: FOl2020/08689 and FOl2020/08717 Date: 26th August 2020 Dear Thank you for your emails of 28th/27th July requesting the following information: FOl2020/08689: ''ARMY Ql. Geographic Locations - What are the top three military Garrisons/Barrack locations within the UK which have the highest percentage proportion of; a) Female Commissioned Officers within its population b) BAME Commissioned Officers within its population c) Female soldiers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers within its population d) BAME soldiers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers within its population Please state percentage of female/BAME composition in the response and total si:ze of population, i.e. Aldershot Garrison - Female commissioned officers make up 10% of a total population of approximately 5,000 commissioned officers with Aldershot Garrison. Q2 - Regimental Concentration - What are the top three individual Regiments/Battalions with the highest percentage proportion of; a) Female Commissioned Officers within its population b) BAME Commissioned Officers within its population c) Female soldiers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers within its population d) BAME soldiers and Senior Non-Commissioned Officers within its population Please state percentage of female/BAME composition in the response and total -

Afghanistan: the Situation of Christian Converts

+*-/ !"#)$./) # .$/0/$*)*!#-$./$)*)1 -/. 7 April 2021 © Landinfo 2021 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33 A P.O. Box 2098 Vika NO-0125 Oslo Tel.: (+47) 23 30 94 70 Ema il: [email protected] www.landinfo.no *0/ )$)!*ҁ. - +*-/. The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information (COI) to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The informa tion is collected a nd analysed in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of Origin Information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. -

“TELLING the STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: a Regional Perspective (2011-2016)

“TELLING THE STORY” Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective (2011-2016) Emma Hooper (ed.) This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. © 2016 CIDOB This monograph has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norway Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Ministry. CIDOB edicions Elisabets, 12 08001 Barcelona Tel.: 933 026 495 www.cidob.org [email protected] D.L.: B 17561 - 2016 Barcelona, September 2016 CONTENTS CONTRIBUTOR BIOGRAPHIES 5 FOREWORD 11 Tine Mørch Smith INTRODUCTION 13 Emma Hooper CHAPTER ONE: MAPPING THE SOURCES OF TENSION WITH REGIONAL DIMENSIONS 17 Sources of Tension in Afghanistan & Pakistan: A Regional Perspective .......... 19 Zahid Hussain Mapping the Sources of Tension and the Interests of Regional Powers in Afghanistan and Pakistan ............................................................................................. 35 Emma Hooper & Juan Garrigues CHAPTER TWO: KEY PHENOMENA: THE TALIBAN, REFUGEES , & THE BRAIN DRAIN, GOVERNANCE 57 THE TALIBAN Preamble: Third Party Roles and Insurgencies in South Asia ............................... 61 Moeed Yusuf The Pakistan Taliban Movement: An Appraisal ......................................................... 65 Michael Semple The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan ....................................................................... -

4Th SOPS to Schriever: Bring It On! Easter Services Available the 50Th Space Wing by Staff Sgt

Spring Fling: egg-citing! More than 1,200 people came out to enjoy the 2007 Spring Fling, which featured a petting zoo, egg scrambles and more. See story and photos on pages 12 and 13. VOL. 9, NO. 14 April 5, 2007 Colorado Springs, Colo. www.schriever.af.mil News Briefs 4th SOPS to Schriever: Bring it on! Easter services available The 50th Space Wing by Staff Sgt. Don Branum Chaplain Support Team 50th Space Wing Public Affairs will conduct a Good Friday worship service Friday at 11 The challenge is on again—who can come a.m. and an Easter Sunday in “fourth”? service Sunday at 8 a.m. in The 4th Space Operations Squadron has the Building 300 Audito- invited everyone on base to take part in the rium here. second-annual 4-Fit Challenge, scheduled for For information on these April 27 at 9:44 a.m. at the Main Fitness Center or other religious ser- and track here. vices, contact the 50th SW The numerology behind the date and time Chaplain Support Team at is signifi cant: April 27 is the fourth Friday of 567-3705. the fourth month. The time corresponds to 4:44 a.m. in the Yankee Time Zone, just east of the Build your relationship International Date Line. Fourth place is the new The Schriever Airman fi rst place; other spots are fi rst, second and third and Family Readiness runners-up. Center, in partnership with This year’s events include a men’s and wom- the Peterson Air Force Base en’s 4x400m relay as well as a 4x1600m coed Spouses Club, will offer two relay. -

Operation Inherent Resolve Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress

OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS JANUARY 1, 2021–MARCH 31, 2021 FRONT MATTER ABOUT THIS REPORT A 2013 amendment to the Inspector General Act established the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) framework for oversight of overseas contingency operations and requires that the Lead IG submit quarterly reports to the U.S. Congress on each active operation. The Chair of the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency designated the DoD Inspector General (IG) as the Lead IG for Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR). The DoS IG is the Associate IG for the operation. The USAID IG participates in oversight of the operation. The Offices of Inspector General (OIG) of the DoD, the DoS, and USAID are referred to in this report as the Lead IG agencies. Other partner agencies also contribute to oversight of OIR. The Lead IG agencies collectively carry out the Lead IG statutory responsibilities to: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight of the operation. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of programs and operations of the U.S. Government in support of the operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, investigations, or evaluations. • Report quarterly to Congress and the public on the operation and on activities of the Lead IG agencies. METHODOLOGY To produce this quarterly report, the Lead IG agencies submit requests for information to the DoD, the DoS, USAID, and other Federal agencies about OIR and related programs. The Lead IG agencies also gather data and information from other sources, including official documents, congressional testimony, policy research organizations, press conferences, think tanks, and media reports. -

Major Commands and Air National Guard

2019 USAF ALMANAC MAJOR COMMANDS AND AIR NATIONAL GUARD Pilots from the 388th Fighter Wing’s, 4th Fighter Squadron prepare to lead Red Flag 19-1, the Air Force’s premier combat exercise, at Nellis AFB, Nev. Photo: R. Nial Bradshaw/USAF R.Photo: Nial The Air Force has 10 major commands and two Air Reserve Components. (Air Force Reserve Command is both a majcom and an ARC.) ACRONYMS AA active associate: CFACC combined force air evasion, resistance, and NOSS network operations security ANG/AFRC owned aircraft component commander escape specialists) squadron AATTC Advanced Airlift Tactics CRF centralized repair facility GEODSS Ground-based Electro- PARCS Perimeter Acquisition Training Center CRG contingency response group Optical Deep Space Radar Attack AEHF Advanced Extremely High CRTC Combat Readiness Training Surveillance system Characterization System Frequency Center GPS Global Positioning System RAOC regional Air Operations Center AFS Air Force Station CSO combat systems officer GSSAP Geosynchronous Space ROTC Reserve Officer Training Corps ALCF airlift control flight CW combat weather Situational Awareness SBIRS Space Based Infrared System AOC/G/S air and space operations DCGS Distributed Common Program SCMS supply chain management center/group/squadron Ground Station ISR intelligence, surveillance, squadron ARB Air Reserve Base DMSP Defense Meteorological and reconnaissance SBSS Space Based Surveillance ATCS air traffic control squadron Satellite Program JB Joint Base System BM battle management DSCS Defense Satellite JBSA Joint Base -

New Engineering Report Finds Privately Built Border Wall Will Fail

New Engineering Report Finds Privately Built Border Wall Will Fail by Jeremy Schwartz and Perla Trevizo This article is co-published with The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan local newsroom that informs and engages with Texans. Sign up for The Brief weekly to get up to speed on their essential coverage of Texas issues. It’s not a matter of if a privately built border fence along the shores of the Rio Grande will fail, it’s a matter of when, according to a new engineering report on the troubled project. The report is one of two new studies set to be filed in federal court this week that found numerous deficiencies in the 3-mile border fence, built this year by North Dakota-based Fisher Sand and Gravel. The reports confirm earlier reporting from ProPublica and The Texas Tribune, which found that segments of the structure were in danger of overturning due to extensive erosion if not fixed and properly maintained. Fisher dismissed the concerns as normal post-construction issues. Donations that paid for part of the border fence are at the heart of an indictment against members of the We Build the Wall nonprofit, which raised more than $25 million to help President Donald Trump build a border wall. Former Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon, We Build the Wall founder Brian Kolfage and two others connected to the organization are accused of siphoning donor money to pay off personal debt and fund lavish lifestyles. All four, who face up to 20 years in prison on each of the two counts they face, have pleaded not guilty, and Bannon has called the charges a plot to stop border wall construction. -

D.D.C. Apr. 20, 2007

Case 1:06-cv-01707-GK Document 20 Filed 04/20/2007 Page 1 of 22 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) RUZATULLAH, et al.,) ) Petitioners, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 06-CV-01707 (GK) ) ROBERT GATES, ) Secretary, United States Department of ) Defense, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) RESPONDENTS’ REPLY TO PETITIONERS’ REPLY AND OPPOSITION TO RESPONDENTS’ MOTION TO DISMISS THE SECOND AMENDED PETITION Respondents respectfully submit this reply brief in response to Petitioners’ Reply and Opposition to Respondents’ Motion to Dismiss the Second Amended Petition. In their opening brief, respondents demonstrated that this Court has no jurisdiction to hear the present habeas petition because the petition, filed by two alien enemy combatants detained at Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan, falls squarely within the jurisdiction-limiting provision of the Military Commissions Act of 2006 (“MCA”), Pub. L. No. 109-366, 120 Stat. 2600 (2006). Respondents also demonstrated that petitioners do not have a constitutional right to habeas relief because under Johnson v. Eisentrager, 339 U.S. 763 (1950), aliens detained abroad, such as petitioners, who have no significant voluntary connections with this country, cannot invoke protections under the Constitution. Subsequent to respondents’ motion to dismiss, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit decided Boumediene v. Bush, 476 F.3d 981 (D.C. Cir.), cert. denied, 127 S.Ct. 1478 (2007), which removes all doubt that the MCA divests federal courts of jurisdiction to review petitions for writs of habeas corpus filed by aliens captured abroad and detained as enemy Case 1:06-cv-01707-GK Document 20 Filed 04/20/2007 Page 2 of 22 combatants in an overseas military base. -

In This Issue

VOLUME VII, ISSUE 36 u NOVEMBER 25, 2009 IN THIS ISSUE: BRIEFS...................................................................................................................................1 IBRAHIM AL-RUBAISH: NEW RELIGIOUS IDEOLOGUE OF AL-QAEDA IN SAUDI ARABIA CALLS FOR REVIVAL OF ASSASSINATION TACTIC By Murad Batal al-Shishani..................................................................................................3 AL-QAEDA IN IRAQ OPERATIONS SUGGEST RISING CONFIDENCE AHEAD OF U.S. MILITARY WITHDRAWAL Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) By Ramzy Mardini..........................................................................................................4 FRENCH OPERATION IN AFGHANISTAN AIMS TO OPEN NEW COALITION SUPPLY ROUTE Terrorism Monitor is a publication By Andrew McGregor............................................................................................................6 of The Jamestown Foundation. The Terrorism Monitor is TALIBAN EXPAND INSURGENCY TO NORTHERN AFGHANISTAN designed to be read by policy- makers and other specialists By Wahidullah Mohammad.................................................................................................9 yet be accessible to the general public. The opinions expressed within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily LEADING PAKISTANI ISLAMIST ORGANIZING POPULAR MOVEMENT reflect those of The Jamestown AGAINST SOUTH WAZIRISTAN OPERATIONS Foundation. As the Pakistani Army pushes deeper into South Waziristan, a vocal political Unauthorized reproduction or challenge