United States Air Force Headquarters, 3Rd Wing Elmendorf AFB, Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Commands and Air National Guard

2019 USAF ALMANAC MAJOR COMMANDS AND AIR NATIONAL GUARD Pilots from the 388th Fighter Wing’s, 4th Fighter Squadron prepare to lead Red Flag 19-1, the Air Force’s premier combat exercise, at Nellis AFB, Nev. Photo: R. Nial Bradshaw/USAF R.Photo: Nial The Air Force has 10 major commands and two Air Reserve Components. (Air Force Reserve Command is both a majcom and an ARC.) ACRONYMS AA active associate: CFACC combined force air evasion, resistance, and NOSS network operations security ANG/AFRC owned aircraft component commander escape specialists) squadron AATTC Advanced Airlift Tactics CRF centralized repair facility GEODSS Ground-based Electro- PARCS Perimeter Acquisition Training Center CRG contingency response group Optical Deep Space Radar Attack AEHF Advanced Extremely High CRTC Combat Readiness Training Surveillance system Characterization System Frequency Center GPS Global Positioning System RAOC regional Air Operations Center AFS Air Force Station CSO combat systems officer GSSAP Geosynchronous Space ROTC Reserve Officer Training Corps ALCF airlift control flight CW combat weather Situational Awareness SBIRS Space Based Infrared System AOC/G/S air and space operations DCGS Distributed Common Program SCMS supply chain management center/group/squadron Ground Station ISR intelligence, surveillance, squadron ARB Air Reserve Base DMSP Defense Meteorological and reconnaissance SBSS Space Based Surveillance ATCS air traffic control squadron Satellite Program JB Joint Base System BM battle management DSCS Defense Satellite JBSA Joint Base -

A Brief History of Air Mobility Command's Air Mobility Rodeo, 1989-2011

Cover Design and Layout by Ms. Ginger Hickey 375th Air Mobility Wing Public Affairs Base Multimedia Center Scott Air Force Base, Illinois Front Cover: A rider carries the American flag for the opening ceremonies for Air Mobility Command’s Rodeo 2009 at McChord AFB, Washington. (US Air Force photo/TSgt Scott T. Sturkol) The Best of the Best: A Brief History of Air Mobility Command’s Air Mobility Rodeo, 1989-2011 Aungelic L. Nelson with Kathryn A. Wilcoxson Office of History Air Mobility Command Scott Air Force Base, Illinois April 2012 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: To Gather Around ................................................................................................1 SECTION I: An Overview of the Early Years ...........................................................................3 Air Refueling Component in the Strategic Air Command Bombing and Navigation Competition: 1948-1986 ...................................................................4 A Signature Event ............................................................................................................5 The Last Military Airlift Command Rodeo, 1990 ...........................................................5 Roundup ................................................................................................................8 SECTION II: Rodeo Goes Air Mobility Command ..................................................................11 Rodeo 1992 ......................................................................................................................13 -

Elmendorf Air Force Base CHPP Decentralization

Case Study - Elmendorf Air Force Base CHPP Decentralization Heating System Decentralization Elmendorf AFB is home to the 3rd Wing, providing the U.S. Pacific Command with highly trained and equipped tactical air superiority forces, all-weather strike assets, command and control platforms, and tactical airlift resources for contingency operations. The Wing flies the F-22, F-15, C-17, C-12 and E-3 aircraft, and maintains a regional medical facility to provide care for all forces in Alaska. Elmendorf is also Headquarters of the 11th Air Force, the Alaskan Command, the Alaska NORAD Region, and 94 associate organizations. Elmendorf AFB has 797 facilities totaling 9.3 million This challenging project scope was completed in two square feet of residential, commercial, industrial, and short Alaska construction seasons. The decentralized administrative space. boilers were commissioned and running and the CHPP Ameresco decommissioned the combined heat and was shut-down on schedule for the start of the critical power plant (CHPP) and installed decentralized boiler heating season. plants (boilers, water treatment, required auxiliaries, and The project also included the demolition of the old building structure as necessary) to serve each of the 130 decommissioned plant and associated steam pits. The facilities (encompassing approximately 1.5 million old plant consisted of the following major equipment: square feet) that were provided steam from the CHPP. • Six (6) 150,000 lb/hr natural gas/jet fuel boilers • Two (2) 9.3 MW steam extraction turbines • One (1) 7.5 MW steam extraction turbine The decommissioned steam distribution system was previously only providing approximately 15% condensate return back to the plant. -

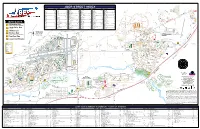

JBER-Base-Map.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L 1 1 JBER STREET INDEX STREET GRID STREET GRID STREET GRID STREET GRID STREET GRID STREET GRID 2nd St ...................................B-9, C-8 33rd St ......................................... C-4 Bluff Rd ........................................ A-9 Femoyer Ave ................................ B-9 Kuter Ave ..............................C-7, C-8 Second St ..................................... I-5 3rd St ........................................... B-9 35th St ......................................... C-5 Bong Ave ...................................... A-8 Fifth St .......................................... I-4 Ladue Rd ......................................H-3 Seventh St .....................................J-5 5th St ........................................... B-9 36th St ......................................... B-6 Boniface Pkwy ............................ E-10 Fighter Dr ..................................... B-7 Lahunchick Rd .............................G-3 Siammer Ave ........................ D-6, D-7 6th Ave ........................................ B-8 37th St ......................................... B-5 Bullard Ave ................................... A-8 Finletter Ave ................................. B-9 Lindbergh Ave .............................. C-7 Sijan Ave .............................. D-6, D-7 9th St .......................................... B-8 38th St ......................................... B-5 Chennault Ave .............................. A-7 First St .....................................H-3,-5 -

GENERAL TOD D. WOLTERS Commander, U.S

GENERAL TOD D. WOLTERS Commander, U.S. European Command Gen. Tod D. Wolters is Commander, U.S. European Command and NATO's Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). He is responsible for one of two U.S. forward-deployed geographic combatant commands whose area of focus spans across Europe, portions of Asia and the Middle East, the Arctic and Atlantic oceans. The command is comprised of more than 60,000 military and civilian personnel and is responsible for U.S. defense operations and relations with NATO and 51 countries. As SACEUR, he is one of NATO's two strategic commanders and commands Allied Command Operations (ACO), which is responsible for the planning and execution of all Alliance operations. He is responsible to NATO's Military Committee for the conduct of all NATO military operations. Gen. Wolters received his commission in 1982 as a graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy. He has commanded the 19th Fighter Squadron, the 1st Operations Group, the 485th Air Expeditionary Wing, the 47th Flying Training Wing, the 325th Fighter Wing, the 9th Air and Space Expeditionary Task Force-Afghanistan, and the 12th Air Force. He has fought in operations Desert Storm, Southern Watch, Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. The general has also served in the Office of the Secretary of the Air Force, as Director of Legislative Liaison and in Headquarters staff positions at U.S. Pacific Command, Headquarters U.S. Air Force and Air Force Space Command. Prior to assuming his current position, the general served as Commander, U.S. Air Forces in Europe; Commander, U.S. -

Air Force Pricelist As of 3/1/2011

Saunders Military Insignia PO BOX 1831 Naples, FL 34106 (239) 776-7524 FAX (239) 776-7764 www.saundersinsignia.com [email protected] Air Force Pricelist as of 3/1/2011 Product # Name Style Years Price 1201 Air Force Branch Tape Patch, sew on, Black 3.00 1216 AVG Blood Chit Flying Tigers Silk 20.00 1218 Desert Storm Chit Silk 8/1990-Current 38.00 1219 Korean War Chit Silk 38.00 1301 336th Fighter Squadron USAF F-15E Fighter Color Patch 10.00 1305 F15E Fighter Weapons School Patch 10.00 1310 EB66 100 Missions Patch 9.00 1311 129th Radio Squadron Mobile Patch, subdued 3.50 1313 416th Bombardment Wing Patch 9.00 1314 353rd Combat Training Squadron Patch 6.50 1315 Air Education and Training Command InstructorPatch 6.50 1317 45th Fighter Squadron USAF Fighter Patch Color 10.00 1318 315th Special Operations Wing Patch 9.00 1321 1st Fighter Wing (English) Patch, Handmade 9.00 1326 100th Fighter Squadron USAF Fighter Patch Color 10.00 1327 302nd Fighter Squadron USAF Fighter Patch Color 23.00 1328 48th Tactical Fighter Squadron USAF Fighter Patch Color 7.50 1329 332nd Fighter Group Patch 10.00 1330 20th Fighter Wing Patch, desert subdued 7.50 1331 21st Special Operations Squadron KnifePatch 6.50 1333 Areospace Defense Command GoosebayPatch Lab 4.00 1335 60th Fighter Squadron USAF Fighter Patch Color 9.00 1336 Spectre AC130 Patch 9.00 1338 Spectre Patience Patch 8.00 1339 162nd Fighter Gp Int Patch 10.00 1341 442nd Tactical Fighter Training SquadronPatch (F111) 8.00 1342 21st Special Operations Squadron patch 7.50 1346 522nd Tactical Fighter Squadron Patch, subdued 3.00 1347 Doppler 1984 Flt. -

NSIAD-96-194 Military Readiness B-272379

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Committee on GAO National Security, House of Representatives August 1996 MILITARY READINESS Data and Trends for April 1995 to March 1996 GOA years 1921 - 1996 GAO/NSIAD-96-194 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-272379 August 2, 1996 The Honorable Floyd Spence Chairman, Committee on National Security House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: As you requested, we have updated our Military Readiness report 1 through March 31, 1996, to determine if the data show significant changes. Also, we reviewed readiness data for selected units participating in the Bosnia operation to see whether the operation has affected readiness. This report provides unclassified readiness information on the four military services. Specifically, it (1) assesses readiness trends of selected units from each service from April 1, 1995, to March 31, 1996, with particular emphasis on units that reported degraded readiness during the prior period and (2) assesses readiness trends (for the period Oct.1, 1995, to Mar. 31, 1996) for selected units that participated in the Bosnia operation. On June 26, 1996, we provided a classified briefing to the staff of the Subcommittee on Military Readiness, House Committee on National Security, on the results of our work. This letter summarizes the unclassified information presented in that briefing. Background The Status of Resources and Training System (SORTS) is the Department of Defense’s (DOD) automated reporting system that identifies the current level of selected resources and training status of a unit—that is, its ability to undertake its wartime mission. -

A Fond Farewell to an Unforgettable Commander

154th WING HAWAII AIR NATIONAL GUARD | JOINT BASE PEARL HARBOR-HICKAM a fond farewell to an unforgettable commander www.154wg.ang.af.mil July | 2019 Inside JULY 2019 STAFF VICE COMMANDER Col. James Shigekane PAO Capt. Justin Leong PA STAFF Master Sgt. Mysti Bicoy 4 7 Tech. Sgt. Alison Bruce-Maldonado Tech. Sgt. Tabitha Hurst Staf Sgt. James Ro Senior Airman Orlando Corpuz Senior Airman Robert Cabuco Senior Airman John Linzmeier Published by 154th Wing Public Afairs Ofce 360 Mamala Bay Drive JBPHH, Hawaii 96853 Phone: (808) 789-0419 10 12 Kuka’ilimoku SUBMISSIONS Articles: Airman Safety App | Page 3 • Articles range from 200 to 2,000 words. All articles should be accompanied by multiple high-resolution images. ANG Director Visits | Page 4 • Include frst names, last names and military ranks. Always verify spelling. | Page 6 • Spell out acronyms, abbreviations and full unit designa- Airman makes progress toward dream college tions on frst reference. Photographs: Subject matter expert exchange • Highest resolution possible: MB fles, not KB. • No retouched photos, no special efects. • Include the photographer’s name and rank, and a held in Indonesia | Page 7 caption: what is happening in the photo, who is pic- tured and the date and location. 204th AS returns to Europe for Swif Response | Page 8 Tis funded Air Force newspaper is an authorized publication for the members of the US military services. Contents of the Ku- ka’ilimoku are not necessarily the ofcial views of, or endorsed Wing Commander's 'Fini-Flight' | Page 10 by, the US Government, the Department of Defense, and the Department of the Air Force or the Hawaii Air National Guard. -

MILITARY READINESS: Data and Trends for April 1995 to March 1996

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Committee on GAO National Security, House of Representatives August 1996 MILITARY READINESS Data and Trends for April 1995 to March 1996 GOA years 1921 - 1996 GAO/NSIAD-96-194 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-272379 August 2, 1996 The Honorable Floyd Spence Chairman, Committee on National Security House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: As you requested, we have updated our Military Readiness report 1 through March 31, 1996, to determine if the data show significant changes. Also, we reviewed readiness data for selected units participating in the Bosnia operation to see whether the operation has affected readiness. This report provides unclassified readiness information on the four military services. Specifically, it (1) assesses readiness trends of selected units from each service from April 1, 1995, to March 31, 1996, with particular emphasis on units that reported degraded readiness during the prior period and (2) assesses readiness trends (for the period Oct.1, 1995, to Mar. 31, 1996) for selected units that participated in the Bosnia operation. On June 26, 1996, we provided a classified briefing to the staff of the Subcommittee on Military Readiness, House Committee on National Security, on the results of our work. This letter summarizes the unclassified information presented in that briefing. Background The Status of Resources and Training System (SORTS) is the Department of Defense’s (DOD) automated reporting system that identifies the current level of selected resources and training status of a unit—that is, its ability to undertake its wartime mission. -

![Pacific Raptors: F-22A Based in Alaska [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4369/pacific-raptors-f-22a-based-in-alaska-pdf-4914369.webp)

Pacific Raptors: F-22A Based in Alaska [PDF]

FREE to delegates at 2008 Singapore Air Show January/February 2008 $7.95 DefenceDefenceDEFENCE CAPABILITIES & HOMELAND SECURITY today 2008 Singapore Air Show issue New trends in UAVs Wedgetail update F-22 AEW&C interview stands up in Alaska Print Post PP424022/00254 AIR7000 Link with US Navy BAMS Pacific Raptors: F-22A based in Alaska Dr Carlo Kopp THE MOST RECENT FLURRY OF PRESS SURROUNDING THE F-22A RAPTOR has been largely focused on the Pentagon decision mid January to keep the F-22A production line open beyond former SecDef Rumsfeld’s arbitrarily imposed production limit of 183 aircraft. Deputy SecDef Gordon England, known to be a high profile advocate of the Joint Strike Fighter, opposed and continues to oppose this decision despite strong pressure from legislators and the US Air Force. Much less visible than the political controversy in The 1st Fighter Wing at Langley AFB, Virginia, was transferred without loss to the F-22 operational Washington surrounding production numbers has the first operational unit to convert to the F-22, and community. All F-22s are currently capable of 2008 Singapore Air Show been the quiet preparation of Elmendorf AFB in in mid December last year the USAF declared Full delivering a pair of JDAM satellite-aided smart Alaska for the permanent basing of the first Pacific Operational Capability for the Langley-based 1st bombs, and flight testing is under way to qualify the Rim F-22s. FW and Virginia Air National Guard’s 192nd Fighter new GBU-39/B Small Diameter Bomb on the F-22, Elmendorf AFB is the hub of US Air Force fighter Wing, both now equipped with the F-22. -

Attu the Forgotten Battle

ATTU THE FORGOTTEN BATTLE John Haile Cloe soldiers, Attu Island, May 14, 1943. (U.S. Navy, NARA 2, RG80G-345-77087) U.S. As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, our national parks and historical places, and providing for enjoyment of life through outdoorprotecting recreation. our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of The Cultural Resource Programs of the National Park Service have responsibilities that include stewardship of historic buildings, museum collections, archeological sites, cultural landscapes, oral and written histories, and ethnographic resources. Our mission is to identify, evaluate and preserve the cultural resources of the park areas and to bring an understanding of these resources to the public. Congress has mandated that we preserve these resources because they are important components of our national and personal identity. Study prepared for and published by the United State Department of the Interior through National Park Servicethe Government Printing Office. Aleutian World War II National Historic Area Alaska Affiliated Areas Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. Attu, the Forgotten Battle ISBN-10:0-9965837-3-4 ISBN-13:978-0-9965837-3-2 2017 ATTU THE FORGOTTEN BATTLE John Haile Cloe Bringing down the wounded, Attu Island, May 14, 1943. (UAA, Archives & Special Collections, Lyman and Betsy Woodman Collection) TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS .........................................................................................................iv LIST OF MAPS ......................................................................................................................... -

SENIOR MASTER SERGEANT (Retired) SCOTT WALKER

U N I T E D S T A T E S A I R F O R C E SENIOR MASTER SERGEANT (retired) SCOTT WALKER Senior Master Sergeant (SMSgt) Scott Walker is Wasilla High School’s Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (AFJROTC) Aerospace Science Instructor (SASI) for AK-20121. He is responsible for training and guidance for the Corps of over 100 cadets, and works in concert with Lt Col Magnan in this capacity. SMSgt Walker monitors cadets for compliance with United States Air Force dress and appearance standards, instructs drill and ceremony procedures and monitors classroom discipline and professionalism. He ensures Air Force guidance regarding the JROTC program is disseminated to the Corps and adhered to, and provides daily instruction in a wide variety of curriculum to include: Aerospace History, Leadership, Space Exploration, Financial Management, Profession of Arms, Flight Characteristics, Wellness and Communications. SMSgt Walker grew up in Phoenix, Arizona, where he broke Al Bundy’s single-game record for touchdowns at Polk High School. Upon completing a solo voyage around the world in a 17-foot rowboat, he was recruited by the FBI to fight organized crime in the rodeo circuit. Having won the Presidential Medal of Freedom and growing bored of ridding the world of evil-doers, he enlisted in the Air Force in 1990. He served for over 20 years as a Tactical Aircraft Maintenance Specialist (2A3X3) and a Professional Military Education Instructor (8T000). SMSgt Walker’s assignments include: 1991-1992, 405th Fighter Wing, 555th Fighter Squadron, Luke AFB, Arizona 1992-2000, 3rd Wing, 90th Fighter Squadron, Elmendorf AFB, Alaska 2000-2003, 1st Space Wing, Imperial TIE-Fighter Commander, Death Star 2003-2007, 18th Wing, 18th Equipment Maintenance Squadron, Kadena AB, Okinawa 2007-2008, 51st Fighter Wing, 51st Maintenance Squadron, Osan AB, Republic of Korea 2008-2010, Air Force One, Command Pilot and Crew Chief Extraordinaire, The White House SMSgt Walker is a veteran of Operation(s) SOUTHERN WATCH, NOBLE EAGLE, IRAQI FREEDOM, The Normandy Invasion and the French and Indian War.