How Government Building Codes and Construction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Types of Plastic and Their Recycle Codes | Quality Logo Products®

7/24/2018 Types of Plastic and Their Recycle Codes | Quality Logo Products® Product Search Your privacy will be protected by redirecting your search to Search Encrypt. Learn More X ALL ABOUT MATERIALS Types of Plastic and Their Recycle Codes Other Lessons in This Course Types of Plastic Plastic is an essential component of many items, including water bottles, combs, and beverage containers. Knowing the difference, as well as the SPI codes, will help you make more informed decisions about recycling. The seven types of plastic include: Polyethylene Terephthalate (PETE or PET) High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Miscellaneous plastics (includes: polycarbonate, polylactide, acrylic, acrylonitrile butadiene, styrene, fiberglass, and nylon) When it comes to promotional giveaways, and even items we use around the house, there is no material more important than plastic. The same can be said for the items we use at the office. Most of our supplies contain at least a little bit of this material. In fact, humans have thus far produced 9.1 billion tons of plastic! For the sake of the environment, it’s important to know the different types of plastic and their uses, as well as the resin identification codes found on each for the sake of recycling. Recycling Codes for Plastic Understanding the different types of plastic can help consumers like you make more informed decisions related to your health and the environment. It’s important to become familiar with an item’s SPI (Society of the Plastics Industry) code, which is also known as a resin identification number and is used to classify the different types of plastic. -

Environmental Impact of Materials in Parks

Material Choices in Public Playground Development Great Lakes Park Training Institute Tim Madeley, Presenter February 21, 2007 Playground Material Choices Overview •CCA Treated Wood •Recycled Plastic Lumber •Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment CCA Treated Wood Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment CCA = Chromated Copper Arsenate •Chromium 66% •Copper 18% •Arsenate 16% •Applied with pressure treatment process Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment • CCA wood treatment has been in use since the 1930’s • Majority of treated wood since 1970’s contained CCA • CCA is a registered chemical pesticide Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment • Growing concern about the possibilit y of arseni c exposure • AiArsenic exposure over time can lead to lung or bladder cancer • In addition to treated wood, CCA exposure occurs naturally in food, air and soil around us all Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment Actual impact to children is based on several factors: • numbfdthlber of days they play on the CCA treated playgrounds each year • number of years they play on the CCA treated playground • amount of arsenic picked up on their hands while they play • amount of arsenic they ingest from their hands during play Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment • In June 2001, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) was petitioned to ban CCA from use on playground equipment • CCA ppyroducers reached a voluntary agreement with the EPA to end the manufacture of CCA for non- industrial uses by December 31, 2003 Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment -

Guide to Plastic Lumber Brenda Platt, Tom Lent and Bill Walsh

hhealbthy bnuilding network JUNE 2005 The Healthy Building Network’s Guide to Plastic Lumber Brenda Platt, Tom Lent and Bill Walsh A report by The Healthy Building Network. A project of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance 927 15th Street, NW, 4th Fl. — Washington, DC 20005 — www.healthybuilding.net About the Institute for Local Self-Reliance Since 1974, the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) has advised citizens, activists, policymakers, and entrepreneurs on how to design and implement state-of-the-art recycling technologies, policies, and programs with a view to strengthening local economies. ILSR’s mission is to provide the conceptual framework, strategies, and information to aid the creation of ecologically sound and economically equitable communities. About the Healthy Building Network A project of ILSR since 2000, the Healthy Building Network (HBN) is a network of national and grassroots organizations dedicated to achieving environmental health and justice goals by transforming the building materials market in order to decrease health impacts to occupants in the built environment – home, school and workplace – while achieving global environmental preservation. HBN’s mission is to shift strategic markets in the building and construction industry away from what we call worst in class building materials, and towards healthier, commercially available alternatives that are competitively priced and equal or superior in performance. Healthy Building Network Institute for Local Self-Reliance 927 15th Street, NW, 4th Floor Washington, DC 20005 phone (202) 898-1610 fax (202) 898-1612 general inquiries, e-mail: [email protected] plastic lumber inquiries, e-mail: [email protected] www.healthybuilding.net Copyright © June 2005 by the Healthy Building Network. -

North American Recycled Plastic Processing Capacity Increases Published January 17, 2020

NERC‐NEWMOA REGIONAL RECYCLING MARKETS COMMITTEE North American Recycled Plastic Processing Capacity Increases Published January 17, 2020 INTRODUCTION The following is a list of increases in North American capacity to process recyclable plastics into products such as plastic lumber, pellets or resins for end‐markets. These increases were announced or completed in 2017 or later. The list covers facilities that have been publicly identified in either the trade or local press. Details of these new plastic processing facilities tend to have less information than similar announcements of expanded recycled end‐market capacity in the paper industry. For instance, announcements of projected opening dates have not, in many cases, been accompanied by press releases or news stories confirming the opening. In addition, few of the facilities are taking mixed plastics. Instead, they are relying on MRFs or other processors to do the initial resin sorting. Each facility listing includes: Name and whether new or expanded facility location projected processing capacity (input) and/or production capacity (output) in tons per year (TPY) 1 product projected opening date This list will be updated as new capacity is announced or new information received. If you have information about capacity expansions not listed here or corrections to the information on this list, please contact Chaz Miller, Chair, NERC‐NEWMOA Regional Recycling Markets Committee, [email protected], 301‐346‐6507. List of acronyms ABS = acrylonitrile butadiene styrene PET = polyethylene terephthalate EPS = expanded polystyrene PP = polypropylene HDPE = high density polyethylene PVC = poly vinyl chloride LDPE = low density polyethylene RPET = recycled PET LLDPE = linear low‐density polyethylene TPM = tons per month PC = polycarbonate TPY = tons per year 1 Some facilities reported in metric tonnes per year. -

Recycled Plastic Lumber (RPL) Products Have Proven to Be Effective Alternatives for Many Applications, Offering High Durability and Requiring Little Maintenance

Recycled Plastic Lumber A Strategic Assessment of its Production, Use and Future Prospects A study sponsored by: the Environment and Plastics Industry Council (EPIC) and Corporations Supporting Recycling (CSR) January 2003 This report was prepared by David Climenhage, under contract, for the Environment & Plastics Industry Council (EPIC) a council of the Canadian Plastics Industry Association (CPIA), and Corporations Supporting Recycling (CSR). The sponsors can be reached at Environment & Plastics Industry Council (EPIC) 5925 Airport Road, Suite 500, Mississauga, Ontario L4V 1W1 Telephone: 905-678-7748 Website: <www.plastics.ca/epic> Corporations Supporting Recycling (CSR) 26 Wellington Street East, Suite 501, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1S2 Telephone: 416-594-3456 Website: <www.csr.org> Although EPIC and CSR have endeavoured to provide accurate and reliable information to the best of their ability, the sponsors cannot be held liable for any loss or damage resulting from the interpretation or application of this information. This information is intended as a guide for use at your discretion and risk. EPIC or CSR cannot guarantee favourable results and assumes no liability in connection with its use. The contents of this publication, in whole or in part, may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. ii Abstract During the 1990s, a number of technologies emerged to utilize recycled plastics in products designed to replace dimensional wood lumber. Since that time, recycled plastic lumber (RPL) products have proven to be effective alternatives for many applications, offering high durability and requiring little maintenance. Plastic lumber products are resilient, weather-resistant, and impervious to rot, mildew, and termites. -

Development of Recycled Plastic Composites for Structural

DEVELOPMENT OF RECYCLED PLASTIC COMPOSITES FOR STRUCTURAL APPLICATIONS FROM CEA PLASTICS by AGRIM BHALLA A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Science Graduate Program in Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering Written under the direction of Thomas Nosker & Mitsunori Denda And approved by _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Development of Plastic Composites for Structural Application from CEA Plastics By AGRIM BHALLA Thesis Director: Thomas Nosker & Mitsunori Denda Plastic waste from consumer electronic appliances (CEAs) such as computer and printer parts including Polystyrene (PS), Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS), Polystyrene (PS) and PC/ABS were collected using handheld FTIR Spectrophotometer. The blends of these plastics with High Density Polyethylene (HDPE) are manufactured under special processing conditions in a single screw compounding injection molding machine. The blends are thermoplastics have high stiffness and strength, which may enhance the mechanical properties of HDPE like tensile modulus, ultimate tensile strength, tensile break and tensile yield. These composites have a potential to be used for the future application of recycled plastic lumber, thus replacing the traditional wood lumber. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would also like to thank my thesis advisor Prof. Thomas Nosker, of the Material Science & Engineering Department at Rutgers, who introduced me to the project and encouraged me to devote my thesis to it. He has shown immense support, guidance and enthusiasm throughout the course of my thesis. I would first like to thank my thesis co- advisor, Prof. Mitsunori Denda, for giving me the opportunity to work with him. -

AZEK Co Investor Presentation

Investor Presentation September 2020 Disclaimer Important Notice Some statements made in this presentation may constitute “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the federal securities laws. Forward-looking statements can be identified by the fact that they do not relate strictly to historical or current facts, but rather are based on current expectations, estimates, assumptions, forecasts or projections about the company’s industry and the company’s business and financial results. Forward-looking statements often include words such as “anticipates,” “estimates,” “expects,” “projects,” “forecasts”, “intends,” “plans,” “believes”, “suggest”, “estimate”, “target”, “should”, “could”, “would”, “may”, “might”, or “will” and words and terms of similar import. Forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are outside our control. Forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, statements about our market opportunity and the potential growth of that market, the potential impact of the COVID-19 public health pandemic, our strategy, outcomes and growth prospects, trends in our industry and markets and the competitive environment in which we operate. Actual results, events, developments, performance or achievements may vary materially from those stated in, or implied by, any forward-looking statements, and the assumptions on which forward-looking statements are based may prove to be incorrect. Factors and uncertainties that might cause such differences in such forecasts -

Plastics 101

PLASTICS 101 INTRODUCTION The versatility of plastic allows it to be used in everything from car to doll parts, from soft drink bottles to the refrigerators in which they are stored. Name the product, and there is likely a plastic found in it. When recycling plastics, search for the number surrounded by the three chasing arrows recycling symbol. There are seven numbers found on plastic, reflecting the seven different types of plastics available in the market. The number is a resin identification code developed by the plastics industry to identify the type of plastic used in the product. These numbers are found on most of the 200 million tons of plastic produced annually. RECYCLING OF PLASTICS In North Castle and throughout Westchester County, plastics 1 through 7 are recycled. Styrofoam is not recycled at this time even though it has a recycling symbol on it. Symbol Name Recycle it? Common Recycled into Commonly Products Unmarked Materials PET or PETE Yes. Must Soda and water Food and Fiber for Polyethylene be empty bottles, beverage carpet, terephthalate and clean. mouthwash containers, fleece wear, bottles, peanut fleece wear, comforter butter and salad furniture and fill, film, dressing carpet, plastic food containers luggage and and non- polyester food containers HDPE Yes. Must Most plastic milk Bottles, Cereal box High density be empty containers, dish including liners, plastic polyethylene and clean. and detergent liquid laundry lumber for bottles, juice detergent, outdoor bottles, butter shampoo, decks, tubs, toiletries conditioner, fencing and Version 20120223 and shampoo vitamin and picnic tables, bottles motor oil pipe, floor bottles, pipes, tiles, buckets, buckets, crates, flower crates, pots, garden flower pots, edging, film, garden floor tiles, edging, film picnic tables, and recycling plastic lumber bins and fencing V or PVC Most PVC Food wrap, Traffic cones Mud flaps, Polyvinyl products bottles for and garden electrical chloride cannot be cooking oil, hoses boxes, recycled. -

Processing and Properties of Plastic Lumber Fernanda A

Chapter Processing and Properties of Plastic Lumber Fernanda A. dos Santos, Leonardo B. Canto, Ana Lúcia N. da Silva, Leila Lea Yuan Visconte and Elen B. A. Vasques Pacheco Abstract Plastic residue can be processed into composites using wood flour, mineral fillers, plant or synthetic fibers to obtain plastic lumber, a substitute material for natural wood. The composition and processing conditions are largely responsible for the final characteristics of the plastic lumber. Factors such as density, particle size and moisture content in the material to be processed require extruders with specific technical characteristics, in order to reduce the residence time of the plastic inside the equipment, maintain a constant feed rate and ensure good degassing and homogenization of the components. The composites can be manufactured using single-screw, co- or counter-rotating conical or parallel twin-screw extruders. Plastic lumber exhibits different physical and mechanical properties from natural wood, including lower stiffness (elastic modulus) and superior weathering resistance. Keywords: recycling, plastic lumber, plastic, reprocessing, property 1. Introduction The increasing generation of plastic waste by industry and in urban areas in recent years has prompted concern in society and efforts to recycle discarded and unused plastic materials [1–3]. Among the alternatives to minimize plastic waste accumulation is using postconsumer plastics to produce plastic lumber as a substi- tute for natural wood [4, 5]. According to the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) [4, 5], the term plastic lumber applies to products made primarily from plastic (with or without additives), with a rectangular cross-section and size typical of wood products used for building. -

What Do Plastic Recycling Symbols Mean Fact Sheet

What Do Plastics Recycling Symbols Mean? Number 1 Plastics: PET or PETE (polyethelene terephthalate) Products: Soft drinks, water and beer bottles, mouthwash bottles, peanut butter containers, salad dressing and vegetable oil containers, microwaveable food trays and clamshells, and more. Recycling: Pick up available through most curbside recycling programs. Recycled Into: Polar fleece, fiber, tote bags, furniture, carpet, paneling, straps, (occasionally) new containers It poses low risk of leaching breakdown products. Recycling rates remain relatively low (around 20 percent), though the material is in high demand by manufacturers. Number 2 Plastics: HDPE (high density polyethylene) Products: Milk jugs, juice bottles, bleach, detergent and household cleaner bottles, shampoo bottles, some trash and shopping bags, motor oil bottles, cereal box liners, and more. Recycling: Pick up available through most curbside recycling programs (some only allow containers with necks). Recycled Into: Laundry detergent bottles, oil bottles, pens, recycling containers, floor tile, drainage pipes, lumber, benches, doghouses, picnic tables, fencing, toothbrushes, and more. HDPE carries low risk of leaching and is readily recyclable into many goods. Number 3 Plastics: PVC (Polyvinyl chloride) or V (Vinyl) Products: Window cleaner and detergent bottles, shampoo bottles, cooking oil bottles, clear food packaging, wire jacketing, medical equipment, siding, windows, piping, and other hard plastic items. Recycling: Rarely recycled; accepted by some plastic lumber makers. Recycled Into: Decks, paneling, mudflaps, roadway gutters, flooring, cables, speed bumps, mats, and more. PVC contains chlorine; manufacturing it can release highly dangerous dioxins. If you must cook with PVC, don’t let the plastic touch the food. Never burn PVC because it releases toxins. -

A Guide to Recycling Codes on Plastic Containers

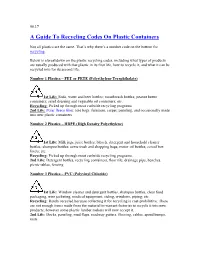

06.17 A Guide To Recycling Codes On Plastic Containers Not all plastics are the same. That’s why there’s a number code on the bottom for recycling. Below is a breakdown on the plastic recycling codes, including what types of products are usually produced with that plastic in its first life, how to recycle it, and what it can be recycled into for its second life. Number 1 Plastics – PET or PETE (Polyethylene Terephthalate) 1st Life: Soda, water and beer bottles; mouthwash bottles; peanut butter containers; salad dressing and vegetable oil containers; etc. Recycling: Picked up through most curbside recycling programs. 2nd Life: Polar fleece fiber, tote bags, furniture, carpet, paneling, and occasionally made into new plastic containers Number 2 Plastics – HDPE (High Density Polyethylene) 1st Life: Milk jugs, juice bottles; bleach, detergent and household cleaner bottles; shampoo bottles; some trash and shopping bags; motor oil bottles; cereal box liners; etc. Recycling: Picked up through most curbside recycling programs. 2nd Life: Detergent bottles, recycling containers, floor tile, drainage pipe, benches, picnic tables, fencing Number 3 Plastics – PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) 1st Life: Window cleaner and detergent bottles, shampoo bottles, clear food packaging, wire jacketing, medical equipment, siding, windows, piping; etc. Recycling: Rarely recycled because collecting it for recycling is cost-prohibitive. There are not enough items made from the material to warrant factories to recycle it into new products; however some plastic lumber makers will now accept it. 2nd Life: Decks, paneling, mud flaps, roadway gutters, flooring, cables, speed bumps, mats Number 4 Plastics – LDPE (Low Density Polyethylene) 1st Life: Squeezable bottles; bread, dry cleaning and shopping bags; tote bags; carpet; etc. -

2020-Poly-Furniture-Catalog.Pdf

Our Story SINCE 1979 From our humble beginnings as a farm market selling flowers and farm fresh eggs to today’s 12-acre outdoor center, Plants and Things USA stands ready to serve all of your outdoor-living needs. And as a family- owned business ourselves, we are dedicated to personally serving you and your family – as well as future generations. In our 40 years, we’ve witnessed nearly two decades of steady growth and transformation of American-made poly furniture. Now in 2020, we are seeing some of the finest quality products. From cozy Adirondack chairs to a relaxing mid-height dining set, we’ve got your style. Plus, create your favorite mood by choosing among many colors ranging from warm earth tones to trendy tropical flavors. But we don’t stop with just furnishing your outdoor living space! In fact, we are pleased to additionally operate two unique indoor furniture stores featuring nearly 175,000 square feet of the finest furniture on the market today. Why not visit us today? 2 2 POLY FURNITURE RECYCLED CONTENT COMMITMENT Have you ever wondered how Berlin Gardens Poly Furniture is made? Many of our customers are unaware that our furniture is made from 96% RECYCLED CONTENT, with the majority coming from post consumer milk bottles collected in community recycling programs. This is an overview of how a milk bottle is recycled and given new life as an Adirondack Chair which will last a lifetime. The Best Furniture Uses the Best Materials The pellets move to a plastic extruder at Tangent where they are remelted and shaped into a variety of “on spec” recycled plastic lumber products.