Types of Plastic and Their Recycle Codes | Quality Logo Products®

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recycling Codes

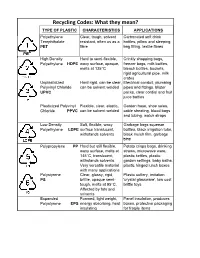

Recycling Codes: What they mean? TYPE OF PLASTIC CHARACTERISTICS APPLICATIONS Polyethylene Clear, tough, solvent Carbonated soft drink Terephthalate resistant, often us as a bottles, pillow and sleeping PET fibre bag filling, textile fibres High Density Hard to semi-flexible, Crinkly shopping bags, Polyethylene HDPE waxy surface, opaque, freezer bags, milk bottles, melts at 135°C bleach bottles, buckets, rigid agricultural pipe, milk crates Unplasticized Hard rigid, can be clear, Electrical conduit, plumbing Polyvinyl Chloride can be solvent welded pipes and fittings, blister UPVC packs, clear cordial and fruit juice bottles Plasticized Polyvinyl Flexible, clear, elastic, Garden hose, shoe soles, Chloride PPVC can be solvent welded cable sheating, blood bags and tubing, watch straps Low Density Soft, flexible, waxy Garbage bags squeeze Polyethylene LDPE surface translucent, bottles, black irrigation tube, withstands solvents black mulch film, garbage bins Polypropylene PP Hard but still flexible, Potato crisps bags, drinking waxy surface, melts at straws, microwave ware, 145°C, translucent, plastic kettles, plastic withstands solvents. garden settings, baby baths, Very versatile material plastic hinged lunch boxes with many applications Polystyrene Clear, glassy, rigid, Plastic cutlery, imitation PS brittle, opaque semi- 'crystal glassware', low cost tough, melts at 95°C. brittle toys Affected by fats and solvents Expanded Foamed, light weight, Panel insulation, produces Polystyrene EPS energy absorbing, heat boxes, protective packaging insulating for fragile items OTHER : Examples are polyamide, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), acrylic, nylon, polyurethane (PU) and phenolics.. -

"Shifting the Pollution Problem: Recycling Plastics in Southern China'

"Shifting the Pollution Problem: Recycling Plastics in Southern China' By K athryn Palko A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the M aster of Arts in International Development Studies at Saint Mary's University Halifax, Nova Scotia November 18,2005 © Kathryn Palko Approved By: Dr. Anne Marie Dalton Supervisor Dr. John Devlin 1st Reader Dr. Julia Sagebien External Examiner Library and Bibliothèque et 1^1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 0-494-15259-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 0-494-15259-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Towards Distributed Recycling with Additive Manufacturing of PET Flake Feedstocks

materials Article Towards Distributed Recycling with Additive Manufacturing of PET Flake Feedstocks Helen A. Little 1, Nagendra G. Tanikella 2, Matthew J. Reich 2, Matthew J. Fiedler 1, Samantha L. Snabes 1 and Joshua M. Pearce 2,3,4,* 1 re:3D Inc., 1100 Hercules STE 220, Houston, TX 77058, USA; [email protected] (H.A.L.); [email protected] (M.J.F.); [email protected] (S.L.S.) 2 Department of Material Science and Engineering, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; [email protected] (N.G.T.); [email protected] (M.J.R.) 3 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA 4 Department of Electronics and Nanoengineering, School of Electrical Engineering, Aalto University, 00076 Espoo, Finland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-906-487-1466 Received: 28 July 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 25 September 2020 Abstract: This study explores the potential to reach a circular economy for post-consumer Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate (rPET) packaging and bottles by using it as a Distributed Recycling for Additive Manufacturing (DRAM) feedstock. Specifically, for the first time, rPET water bottle flake is processed using only an open source toolchain with Fused Particle Fabrication (FPF) or Fused Granular Fabrication (FGF) processing rather than first converting it to filament. In this study, first the impact of granulation, sifting, and heating (and their sequential combination) is quantified on the shape and size distribution of the rPET flakes. Then 3D printing tests were performed on the rPET flake with two different feed systems: an external feeder and feed tube augmented with a motorized auger screw, and an extruder-mounted hopper that enables direct 3D printing. -

Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: a Global Evaluation of Sources Authors: Julien Boucher, Damien Friot

Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: a Global Evaluation of Sources Authors: Julien Boucher, Damien Friot INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: a Global Evaluation of Sources Authors: Julien Boucher, Damien Friot The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2017 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Boucher, J. and Friot D. (2017). Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. 43pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1827-9 DOI: dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2017.01.en Authors: Julien Boucher EA – Shaping Environmental Action & University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland // HES-SO, HEIG-VD, Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland Damien Friot EA – Shaping Environmental Action www.shaping-ea.com [email protected] Editor: Carl Gustaf Lundin and João Matos de Sousa External reviewers: Francis Vorhies (Earthmind, http://earthmind.org) François Galgani (IFREMER, Laboratoire LER/PAC) Mathieu Pernice (University of Technology, Sydney) Doug Woodring (www.oceanrecov.org) Designed by: Imre Sebestyén jr. -

The Facts About Plastic Bags: Recyclable, Affordable, and Convenient

THE FACTS ABOUT PLASTIC BAGS: RECYCLABLE, AFFORDABLE, AND CONVENIENT Plastic bags are 100% recyclable, reusable, made from natural gas, not oil, and a sustainable choice for consumers, communities and businesses. What’s more, the plastic bag manufacturing and recycling industry is a uniquely American industry that employs more than 30,000 Americans in 349 plants across the country, including more than 1,000 people in Washington state. Bans and taxes on plastic bags are misguided policies that don’t make sense. They don’t help the environment, force less sustainable options, threaten local manufacturing jobs and raise grocery costs for consumers. Instead of banning a reusable, 100% recyclable, American-made product, recycling solutions can help reduce litter, give consumers a choice, and protect American jobs. Plastic grocery bags are the best checkout option for our environment On a per bag basis, plastic bags are more resource efficient, reduce landfill waste and generate fewer greenhouse gas emissions. o They take up a lot less space in a landfill: 1,000 plastic bags weigh 13 pounds; 1,000 paper bags weigh 114 pounds.i o They generate 80 % less waste than paper bags.ii American plastic bags are made from natural gas, NOT oil. In the U.S., 85 percent of the raw material used to make plastic bags is produced from natural gas.iii Recycled plastic bags are used to make new plastic bags and building products, such as backyard decks, playground equipment, and fences. Bans haven’t worked in other places, and don’t protect the environment A ban would make no difference in litter reduction since plastic bags only make up a tiny fraction (less than 0.5 %) of the U.S. -

Improving Plastics Management: Trends, Policy Responses, and the Role of International Co-Operation and Trade

Improving Plastics Management: Trends, policy responses, and the role of international co-operation and trade POLICY PERSPECTIVES OECD ENVIRONMENT POLICY PAPER NO. 12 OECD . 3 This Policy Paper comprises the Background Report prepared by the OECD for the G7 Environment, Energy and Oceans Ministers. It provides an overview of current plastics production and use, the environmental impacts that this is generating and identifies the reasons for currently low plastics recycling rates, as well as what can be done about it. Disclaimers This paper is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and the arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. For Israel, change is measured between 1997-99 and 2009-11. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. Copyright You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. -

Environmental Impact of Materials in Parks

Material Choices in Public Playground Development Great Lakes Park Training Institute Tim Madeley, Presenter February 21, 2007 Playground Material Choices Overview •CCA Treated Wood •Recycled Plastic Lumber •Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment CCA Treated Wood Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment CCA = Chromated Copper Arsenate •Chromium 66% •Copper 18% •Arsenate 16% •Applied with pressure treatment process Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment • CCA wood treatment has been in use since the 1930’s • Majority of treated wood since 1970’s contained CCA • CCA is a registered chemical pesticide Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment • Growing concern about the possibilit y of arseni c exposure • AiArsenic exposure over time can lead to lung or bladder cancer • In addition to treated wood, CCA exposure occurs naturally in food, air and soil around us all Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment Actual impact to children is based on several factors: • numbfdthlber of days they play on the CCA treated playgrounds each year • number of years they play on the CCA treated playground • amount of arsenic picked up on their hands while they play • amount of arsenic they ingest from their hands during play Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment • In June 2001, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) was petitioned to ban CCA from use on playground equipment • CCA ppyroducers reached a voluntary agreement with the EPA to end the manufacture of CCA for non- industrial uses by December 31, 2003 Green Playgrounds CCA wood treatment -

Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in the Great Lakes Basin

Attachment 2 WQB Appearance POLYBROMINATED DIPHENYL ETHERS IN THE GREAT LAKES BASIN FINAL REPORT October 30, 2015 SUBMITTED TO: INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION - GREAT LAKES WATER QUALITY BOARD LEGACY ISSUES WORKING GROUP SUBMITTED BY DUNCAN BURY CONSULTING 193 Cowley Avenue, Ottawa, ON, K1Y 0G8 [email protected]; (613) 729-0499 In association with and Attachment 2 WQB Appearance This page intentionally left blank. Attachment 2 WQB Appearance ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The consulting team would like to acknowledge the contributions and information provided by the following government officials, experts and stakeholders who kindly agreed to be interviewed for this report: Chris Affeldt, Pollution Prevention Program Analyst, Michigan Department of Environmental Quality David Bell, Research Scientist, Environmental Impact Analysis Unit, Minnesota Department of Health David Berryman, Water Quality Analyst, Québec Ministry of Sustainable Development, Environment and the Fight against Climate Change Cindy Coutts, President, Canada, SIMS Recycling Solutions Miriam Diamond, Professor, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario Sean De Vries, Director Recycling Qualification Office, Electronic Products Recycling Association Dave Foulkes, Environmental Specialist, Office of Compliance Assistance and Pollution Prevention (OCAPP), Ohio Environmental Protection Agency Brent Goetz, Inspector, Hazardous Waste, Northwest District Office, Ohio Environmental Protection Agency Bradley Grams, Federal Chemical Programs Coordinator, Land and Chemicals -

Plastic Industry Awareness of the Ocean Plastics Problem

Fueling Plastics Plastic Industry Awareness of the Ocean Plastics Problem • Scientists became aware of the ocean plastics problem in the 1950s, and understanding of the nature and severity of the problem grew over the next decades. • The major chemical and petroleum companies and industry groups were aware of the ocean plastics problem no later than the 1970s. • Plastics producers have often taken the position that they are only responsible for plastic waste in the form of resin pellets, and that other forms of plastic waste are out of their control. The use of plastics in consumer resins and the fossil fuel companies the twentieth century. Early observ- goods has been expanding exponen- supplying them with chemical feed- ers concerned about marine plas- tially since the late 1940s. Within stocks — have known about this tics were specifically worried about years of that expansion beginning, problem and for how long. The re- marine animals becoming entan- observers began to document plas- mainder of this document presents a gled in discarded fishing gear and tic pollution in the environment, brief overview of the history of pub- other plastic wastes. As noted by including in the world’s oceans. lic and industry awareness of marine the United States’ National Oce- Plastic is a pollutant of unique con- plastic pollution. Although this his- anic and Atmospheric Administra- cern because it is durable over long torical account is detailed, it is far tion (NOAA), “[p]rior to the 1950s periods of time and its effects accu- from comprehensive, and additional much of the fishing gear and land- mulate as more of it is produced and research is forthcoming. -

Guide to Plastic Lumber Brenda Platt, Tom Lent and Bill Walsh

hhealbthy bnuilding network JUNE 2005 The Healthy Building Network’s Guide to Plastic Lumber Brenda Platt, Tom Lent and Bill Walsh A report by The Healthy Building Network. A project of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance 927 15th Street, NW, 4th Fl. — Washington, DC 20005 — www.healthybuilding.net About the Institute for Local Self-Reliance Since 1974, the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) has advised citizens, activists, policymakers, and entrepreneurs on how to design and implement state-of-the-art recycling technologies, policies, and programs with a view to strengthening local economies. ILSR’s mission is to provide the conceptual framework, strategies, and information to aid the creation of ecologically sound and economically equitable communities. About the Healthy Building Network A project of ILSR since 2000, the Healthy Building Network (HBN) is a network of national and grassroots organizations dedicated to achieving environmental health and justice goals by transforming the building materials market in order to decrease health impacts to occupants in the built environment – home, school and workplace – while achieving global environmental preservation. HBN’s mission is to shift strategic markets in the building and construction industry away from what we call worst in class building materials, and towards healthier, commercially available alternatives that are competitively priced and equal or superior in performance. Healthy Building Network Institute for Local Self-Reliance 927 15th Street, NW, 4th Floor Washington, DC 20005 phone (202) 898-1610 fax (202) 898-1612 general inquiries, e-mail: [email protected] plastic lumber inquiries, e-mail: [email protected] www.healthybuilding.net Copyright © June 2005 by the Healthy Building Network. -

North American Recycled Plastic Processing Capacity Increases Published January 17, 2020

NERC‐NEWMOA REGIONAL RECYCLING MARKETS COMMITTEE North American Recycled Plastic Processing Capacity Increases Published January 17, 2020 INTRODUCTION The following is a list of increases in North American capacity to process recyclable plastics into products such as plastic lumber, pellets or resins for end‐markets. These increases were announced or completed in 2017 or later. The list covers facilities that have been publicly identified in either the trade or local press. Details of these new plastic processing facilities tend to have less information than similar announcements of expanded recycled end‐market capacity in the paper industry. For instance, announcements of projected opening dates have not, in many cases, been accompanied by press releases or news stories confirming the opening. In addition, few of the facilities are taking mixed plastics. Instead, they are relying on MRFs or other processors to do the initial resin sorting. Each facility listing includes: Name and whether new or expanded facility location projected processing capacity (input) and/or production capacity (output) in tons per year (TPY) 1 product projected opening date This list will be updated as new capacity is announced or new information received. If you have information about capacity expansions not listed here or corrections to the information on this list, please contact Chaz Miller, Chair, NERC‐NEWMOA Regional Recycling Markets Committee, [email protected], 301‐346‐6507. List of acronyms ABS = acrylonitrile butadiene styrene PET = polyethylene terephthalate EPS = expanded polystyrene PP = polypropylene HDPE = high density polyethylene PVC = poly vinyl chloride LDPE = low density polyethylene RPET = recycled PET LLDPE = linear low‐density polyethylene TPM = tons per month PC = polycarbonate TPY = tons per year 1 Some facilities reported in metric tonnes per year. -

Recycled Plastic Lumber (RPL) Products Have Proven to Be Effective Alternatives for Many Applications, Offering High Durability and Requiring Little Maintenance

Recycled Plastic Lumber A Strategic Assessment of its Production, Use and Future Prospects A study sponsored by: the Environment and Plastics Industry Council (EPIC) and Corporations Supporting Recycling (CSR) January 2003 This report was prepared by David Climenhage, under contract, for the Environment & Plastics Industry Council (EPIC) a council of the Canadian Plastics Industry Association (CPIA), and Corporations Supporting Recycling (CSR). The sponsors can be reached at Environment & Plastics Industry Council (EPIC) 5925 Airport Road, Suite 500, Mississauga, Ontario L4V 1W1 Telephone: 905-678-7748 Website: <www.plastics.ca/epic> Corporations Supporting Recycling (CSR) 26 Wellington Street East, Suite 501, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1S2 Telephone: 416-594-3456 Website: <www.csr.org> Although EPIC and CSR have endeavoured to provide accurate and reliable information to the best of their ability, the sponsors cannot be held liable for any loss or damage resulting from the interpretation or application of this information. This information is intended as a guide for use at your discretion and risk. EPIC or CSR cannot guarantee favourable results and assumes no liability in connection with its use. The contents of this publication, in whole or in part, may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. ii Abstract During the 1990s, a number of technologies emerged to utilize recycled plastics in products designed to replace dimensional wood lumber. Since that time, recycled plastic lumber (RPL) products have proven to be effective alternatives for many applications, offering high durability and requiring little maintenance. Plastic lumber products are resilient, weather-resistant, and impervious to rot, mildew, and termites.