Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in the Great Lakes Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recycling Codes

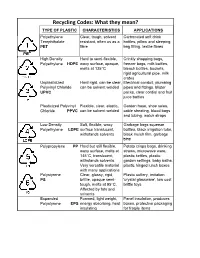

Recycling Codes: What they mean? TYPE OF PLASTIC CHARACTERISTICS APPLICATIONS Polyethylene Clear, tough, solvent Carbonated soft drink Terephthalate resistant, often us as a bottles, pillow and sleeping PET fibre bag filling, textile fibres High Density Hard to semi-flexible, Crinkly shopping bags, Polyethylene HDPE waxy surface, opaque, freezer bags, milk bottles, melts at 135°C bleach bottles, buckets, rigid agricultural pipe, milk crates Unplasticized Hard rigid, can be clear, Electrical conduit, plumbing Polyvinyl Chloride can be solvent welded pipes and fittings, blister UPVC packs, clear cordial and fruit juice bottles Plasticized Polyvinyl Flexible, clear, elastic, Garden hose, shoe soles, Chloride PPVC can be solvent welded cable sheating, blood bags and tubing, watch straps Low Density Soft, flexible, waxy Garbage bags squeeze Polyethylene LDPE surface translucent, bottles, black irrigation tube, withstands solvents black mulch film, garbage bins Polypropylene PP Hard but still flexible, Potato crisps bags, drinking waxy surface, melts at straws, microwave ware, 145°C, translucent, plastic kettles, plastic withstands solvents. garden settings, baby baths, Very versatile material plastic hinged lunch boxes with many applications Polystyrene Clear, glassy, rigid, Plastic cutlery, imitation PS brittle, opaque semi- 'crystal glassware', low cost tough, melts at 95°C. brittle toys Affected by fats and solvents Expanded Foamed, light weight, Panel insulation, produces Polystyrene EPS energy absorbing, heat boxes, protective packaging insulating for fragile items OTHER : Examples are polyamide, acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), acrylic, nylon, polyurethane (PU) and phenolics.. -

"Shifting the Pollution Problem: Recycling Plastics in Southern China'

"Shifting the Pollution Problem: Recycling Plastics in Southern China' By K athryn Palko A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the M aster of Arts in International Development Studies at Saint Mary's University Halifax, Nova Scotia November 18,2005 © Kathryn Palko Approved By: Dr. Anne Marie Dalton Supervisor Dr. John Devlin 1st Reader Dr. Julia Sagebien External Examiner Library and Bibliothèque et 1^1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 0-494-15259-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 0-494-15259-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Types of Plastic and Their Recycle Codes | Quality Logo Products®

7/24/2018 Types of Plastic and Their Recycle Codes | Quality Logo Products® Product Search Your privacy will be protected by redirecting your search to Search Encrypt. Learn More X ALL ABOUT MATERIALS Types of Plastic and Their Recycle Codes Other Lessons in This Course Types of Plastic Plastic is an essential component of many items, including water bottles, combs, and beverage containers. Knowing the difference, as well as the SPI codes, will help you make more informed decisions about recycling. The seven types of plastic include: Polyethylene Terephthalate (PETE or PET) High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Miscellaneous plastics (includes: polycarbonate, polylactide, acrylic, acrylonitrile butadiene, styrene, fiberglass, and nylon) When it comes to promotional giveaways, and even items we use around the house, there is no material more important than plastic. The same can be said for the items we use at the office. Most of our supplies contain at least a little bit of this material. In fact, humans have thus far produced 9.1 billion tons of plastic! For the sake of the environment, it’s important to know the different types of plastic and their uses, as well as the resin identification codes found on each for the sake of recycling. Recycling Codes for Plastic Understanding the different types of plastic can help consumers like you make more informed decisions related to your health and the environment. It’s important to become familiar with an item’s SPI (Society of the Plastics Industry) code, which is also known as a resin identification number and is used to classify the different types of plastic. -

Towards Distributed Recycling with Additive Manufacturing of PET Flake Feedstocks

materials Article Towards Distributed Recycling with Additive Manufacturing of PET Flake Feedstocks Helen A. Little 1, Nagendra G. Tanikella 2, Matthew J. Reich 2, Matthew J. Fiedler 1, Samantha L. Snabes 1 and Joshua M. Pearce 2,3,4,* 1 re:3D Inc., 1100 Hercules STE 220, Houston, TX 77058, USA; [email protected] (H.A.L.); [email protected] (M.J.F.); [email protected] (S.L.S.) 2 Department of Material Science and Engineering, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; [email protected] (N.G.T.); [email protected] (M.J.R.) 3 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA 4 Department of Electronics and Nanoengineering, School of Electrical Engineering, Aalto University, 00076 Espoo, Finland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-906-487-1466 Received: 28 July 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 25 September 2020 Abstract: This study explores the potential to reach a circular economy for post-consumer Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate (rPET) packaging and bottles by using it as a Distributed Recycling for Additive Manufacturing (DRAM) feedstock. Specifically, for the first time, rPET water bottle flake is processed using only an open source toolchain with Fused Particle Fabrication (FPF) or Fused Granular Fabrication (FGF) processing rather than first converting it to filament. In this study, first the impact of granulation, sifting, and heating (and their sequential combination) is quantified on the shape and size distribution of the rPET flakes. Then 3D printing tests were performed on the rPET flake with two different feed systems: an external feeder and feed tube augmented with a motorized auger screw, and an extruder-mounted hopper that enables direct 3D printing. -

Plastic Bag Recycling Program Faqs

Plastic Bag Recycling Program FAQs What type of plastic is recyclable under the Plastic Bag Recycling Program? Polyethylene plastic film type material is what we are looking for in this program. These items are generally a softer, somewhat “stretchy” plastic, usually with a less shiny finish. For example, if you were to try to tear a grocery bag or dry-cleaning bag, it would stretch and pull as it tears, giving it a ragged edge. If labeled, it would have a 2 or 4 recycling symbol. What type of plastic is not acceptable under the Plastic Bag Recycling Program? Plastics that are harder and “crinkly” that would give a straight finish when torn. Any plastics that have a 1,3,5,6, or 7 recycling symbols. These plastics are made with products that are not accepted in our program. Are plastic bottles, caps and rings on six-pack beverages acceptable? No, these items are a different type of plastic and are not recyclable in this program. Cereal bags are included on the list. Does this mean the plastic bags from regular cardboard boxes of cereal and not the plastic bags that some bargain brand cereals come in? Yes, that’s correct. Only the plastic bags inside the cardboard cereal bags are acceptable. Are used FoodSaver bags, that have been adequately rinsed out, accepted? No, these bags are made from a polyethylene and nylon blend. The nylon makes them unacceptable. Some breads come in regular plastic bread bags but have a stiffer, sort of cellophane-like, inner bag. Are the inner wrappers accepted too? No, the inner cellophane type material is not accepted because it is a different type of plastic. -

Hazardous Waste in Australia 2017 30 MAY 2017

Final Hazardous Waste in Australia 2017 30 MAY 2017 PREPARED FOR Department of the Environment and Energy PREPARED IN ASSOCIATION WITH Report title Hazardous Waste in Australia 2017 Client Department of the Environment and Energy Status Final Author(s) Geoff Latimer, Ascend Waste and Environment Pty Ltd Reviewer(s) Joe Pickin, Luke Richmond Project number P726 Report date 30 May 2017 Contract date 3 0 May 2016 Information current to 30 June 2017 Copyright Department of Environment and Energy and Blue Environment Pty Ltd Disclaimer This report has been prepared for Department of the Environment and Energy in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment dated 30 May 2016, and is based on the assumptions and exclusions set out in our scope of work. Information in this document is current as of 30 June 2017. While all professional care has been undertaken in preparing this report, Blue Environment Pty Ltd cannot accept any responsibility for any use of or reliance on the contents of this report by any third party. The mention of any company, product or process in this report does not constitute or imply endorsement by Blue Environment Pty Ltd. © Department of Environment and Energy and Blue Environment Pty Ltd Blue Environment Pty Ltd ABN 78 118 663 997 Suite 208, 838 Collins St, Docklands Vic 3008 Email: [email protected] Web: www.blueenvironment.com.au Phone: +61 3 9081 0440 / +61 3 5426 3536 Contents At a glance ................................................................................................................................. -

EN | Waste for Dummies BA

Waste for Dummies in Bratislava Instructions on how to manage and sort waste for family, friends and everyone, who is so perplexed as we were. B&B powered by INCIEN Barbora Šablová & Barbora Nedeľková Waste for Dummies in Bratislava The first basic rule is the waste prevention. If we don't create waste, we don't have to be bothered by sorting it. In waste prevention as well as waste management, we follow the waste management hierarchy: Barbora Šablová & Barbora Nedeľková Waste for Dummies in Bratislava The first rule is to prevent waste and only then to sort and recycle. The creation of mixed municipal waste is the last step. In order to achieve this, we follow these 5 rules - 5R: If I really need to buy something new, first I consider the packaging, locality, quality, fairness and the way of production and processing (the less things, the less problems REFUSE with repairs, cleaning, forgetting what I have or if I have it ...) and I refuse packaging, and products I don't really need or don't know how to reuse, sort or compost. I refuse leaflets and free promotional items. Reducing the amount of things I buy. With every new item I buy, I produce waste - whether it's during the manufacture, packaging, or transport. Finally, the item itself REDUCE becomes waste. That is why every purchase needs to be well-considered and especially I try to avoid impulsive shopping and purchasing purposeless things (eg, the apple pitter ...). It is important to re-use things. If I've finished to use something, I think of another way of using it, before throwing it away. -

A Guide to Recycling Codes on Plastic Containers

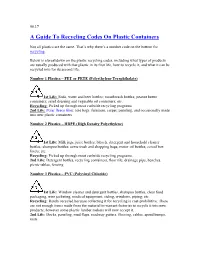

06.17 A Guide To Recycling Codes On Plastic Containers Not all plastics are the same. That’s why there’s a number code on the bottom for recycling. Below is a breakdown on the plastic recycling codes, including what types of products are usually produced with that plastic in its first life, how to recycle it, and what it can be recycled into for its second life. Number 1 Plastics – PET or PETE (Polyethylene Terephthalate) 1st Life: Soda, water and beer bottles; mouthwash bottles; peanut butter containers; salad dressing and vegetable oil containers; etc. Recycling: Picked up through most curbside recycling programs. 2nd Life: Polar fleece fiber, tote bags, furniture, carpet, paneling, and occasionally made into new plastic containers Number 2 Plastics – HDPE (High Density Polyethylene) 1st Life: Milk jugs, juice bottles; bleach, detergent and household cleaner bottles; shampoo bottles; some trash and shopping bags; motor oil bottles; cereal box liners; etc. Recycling: Picked up through most curbside recycling programs. 2nd Life: Detergent bottles, recycling containers, floor tile, drainage pipe, benches, picnic tables, fencing Number 3 Plastics – PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) 1st Life: Window cleaner and detergent bottles, shampoo bottles, clear food packaging, wire jacketing, medical equipment, siding, windows, piping; etc. Recycling: Rarely recycled because collecting it for recycling is cost-prohibitive. There are not enough items made from the material to warrant factories to recycle it into new products; however some plastic lumber makers will now accept it. 2nd Life: Decks, paneling, mud flaps, roadway gutters, flooring, cables, speed bumps, mats Number 4 Plastics – LDPE (Low Density Polyethylene) 1st Life: Squeezable bottles; bread, dry cleaning and shopping bags; tote bags; carpet; etc. -

Zero Waste Plan a ROADMAP to REDUCE, RECAPTURE, RECYCLE and REINVENT SFO’S MATERIAL SYSTEM Executive Summary

Zero Waste Plan A ROADMAP TO REDUCE, RECAPTURE, RECYCLE AND REINVENT SFO’S MATERIAL SYSTEM Executive Summary Our Goal Our Plan San Francisco International Airport (SFO) has set This document lays out SFO Airport’s Zero Waste a Strategic Plan goal of becoming the world’s Plan, a suite of measures to achieve zero waste by first ‘zero waste’ airport by 2021. Zero waste, as 2021 and work towards becoming a “Closed-Loop defined by the Zero Waste Alliance, is to divert at Circular Campus” in the years that follow. Pivoting least 90% of waste from landfills and incinerators from a landfill-centric system will require the airport’s using methods like recycling and composting. dynamic group of materials managers to track new metrics, test new technologies and behavior-focused Our Status campaigns, and team up with new stakeholders. In Fiscal Year 2015-16, SFO Airport generated 12,200 tons, or 26,888,800 pounds, of solid waste. A recent study confirmed that more than 95% of this waste was compostable or recyclable, so for SFO, zero waste is already within reach. By implementing this plan, SFO can become a leader in addressing some of the largest challenges of our time – climate change, human health risks, ecosystem destruction, and more. Table of Contents Our Goal . 4 What is Zero Waste? . 5 Why Zero? . 5 Plan Development . 6 Scope of Materials . 6 Baseline Data on SFO’s Current Materials System . 7 SFO’s Six-Step Zero Waste Plan . 19 1. Metrics Management . 21 2. Material Recovery Area Upgrades . 23 3. Maximizing People Power . -

Plastics – the Facts 2013 an Analysis of European

Plastics – the Facts 2013 An analysis of European latest plastics production, demand and waste data The data presented in this report was collected by PlasticsEurope (the Association of Plastics Manufacturers in Europe), EuPC (the European Plastics Converters), Plastics Recyclers Europe and EPRO (the European Association of Plastics Recycling and Recovery Organisations). PlasticsEurope’s Market Research and Statistics Group (PEMRG) provided input on the production of and demand for plastics raw materials. Consultic Marketing & Industrieberatung GmbH helped assess waste generation and recovery data. Official statistics from European or national authorities and waste management organisations have been used for recovery and trade data, where available. Research or expertise from consultants completed gaps. Figures cannot always be directly compared with those of previous years due to changes in estimates. Some estimates from previous years have been revised in order to track progress, e.g. for use and recovery of plastics across Europe over the past decade. All figures and graphs in this report show data for EU-27 plus Norway and Switzerland, which is referred to as Europe for the purposes of abbreviation – other country groups are explicitly listed. A success story A success story 1850 Celluloid 1970 Versatile and highly inflammable Offering lightweight, 1st plastic material made of cellulose which high shock absorption and bumpers was used for the production of esthetic performance. the first films but also jewellery. 1939 Nylon 1907 The world’s first truly synthetic Bakelite fibre offering durability. The robust phenolic resin was used for the production of telephones, radios and light switches for instance. Courtesy of DuPont 2013 Plastic prostheses Thanks to plastics, we can push 2 our limits much further. -

Universal Recycling Symbol with Different Recycling Codes and Materials’ Abbreviations

Although often confused, “biodegradable” is distinct in meaning from “compostable”. While “biodegradable” simply means that a material (of any kind) can be disintegrated by microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, etc.), WHAT DOES IT MEAN? WHERE DO I PUT IT ? “compostable” only refers to the degradation of organic matter under composting conditions generating compost (or humus). REMEMBER: what is compostable is always biodegradable, not viceversa! TIDYMAN PLASTICS CONTAINER! ORGANIC CONTAINER! Composting is usually an aerobic process (taking place in presence of recycling oxygen). In lack of oxygen it is defined as anaerobic digestion (which Don’t waste your litter in the environment! code reduces the emission of landfill gas into the atmosphere). Be a responsible citizen! Composting can be done at home, or at an industrial scale under material controlled conditions and through different procedures (see link). abbreviation The Resin Identification Codes (above) are the combination of the Universal Recycling Symbol with different recycling codes and materials’ abbreviations. These are found on packaging and products and allow to identify the material of which they are made of, thus to understand where the products has to be thrown away to be recycled. (Plastics recycling numbers range from #01 to #19 depending on the specific type of plastic resin. Numbers from #07 to #19 are classified as “OTHERS” and cannot be compostable at home industrial recycled). under non-controlled compost: special UNIVERSAL RECYCLING SYMBOL → Different variants of all these symbols exist, depending on the Universal Recycling Symbol used, conditions conditions needed however they all mean the same. e.g. PET BIODEGRADABLE: or or CHECK THE MATERIAL! METALS ?!? THE CASE OF Almost all materials are potentially biodegradable, each one requiring a different time of degradation depending on the material. -

On November 13, 2018, the Wildwood City Council Voted to Switch to Dual-Stream Recycling Citywide Starting January 1, 2019

WEBSITE COPY: On November 13, 2018, the Wildwood City Council voted to switch to dual-stream recycling citywide starting January 1, 2019. Due to recent national initiatives to reduce waste and contamination throughout the United States, Resource Management’s Earth City Materials Recovery Facility notified our service provider, Meridian Waste, that as of November 1, they will no longer accept single-stream recyclables collected curbside from residential customers, which includes Wildwood residents. Since this new process requires residents to take some recyclables to a drop-off location within Wildwood, we created this FAQ to answer questions you may have. This FAQ will be updated as new information becomes available. If you have questions not covered in this document, please contact us at [email protected]. Wildwood Recycling Changes effective January 1, 2019 1. What is dual-stream recycling? a. Dual-stream recycling means that you separate different types of recycled materials. Items that are still eligible for curbside pickup include: plastic containers with recycling codes of 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 (non-black), aluminum, tin and steel cans. b. This also means that residents will need to drop recyclables off at drop-off locations throughout the city. These include: corrugated papers (cardboard), mixed papers and glass. Drop-off locations are being set up by Meridian at no cost to residents or the city. We will publicize the locations when we have them. c. Both the City and Meridian will be providing information to residents in the mail, on the City’s website, and in the City’s social media channels about this change.