Review of Ophthalmic Tumors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skin and Breast Disease in the Differential Diagnosis of Chest Pain

Skin and breast disease in the differential diagnosis of chest pain Author Muir, Jim, Yelland, Michael Published 2010 Journal Title Medical Clinics of North America DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2010.01.006 Copyright Statement © 2010 Elsevier. This is the author-manuscript version of this paper. Reproduced in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/33712 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au ARTICLE IN PRESS 1 2 Skin and Breast 3 4 Disease in the 5 6 Differential 7 8 Diagnosis of 9 10 Chest Pain 11 12 a, b ½Q2½ Q3 Jim Muir *, Michael Yelland ½Q4½ Q5 KEYWORDS 13 14 Chest pain Skin diseases Herpes zoster PROOF 15 Breast Neoplasm 16 17 18 Pain is not a symptom commonly associated with skin disease. This is especially so 19 when considering the known skin problems that have a presenting symptom of chest 20 pain that could potentially be confused with chest pain from other causes. 21 22 PAINFUL SKIN CONDITIONS 23 24 Several extremely painful and tender skin conditions present with dramatic clinical 25 signs. Inflammatory disorders such as pyoderma gangrenosum, skin malignancies, 26 both primary and secondary, acute bacterial infections such as erysipelas or cellulitis, 27 and multiple other infections are commonly extremely painful and tender. As these 28 conditions manifest with obvious skin signs such as swelling, erythema, localized 29 tenderness, fever, lymphangitis, and lymphadenopathy, there is little chance of misdi- 30 agnosis of symptoms as caused by anything other than a cutaneous pathology. -

Benign Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of the Vulva

Please do not remove this page Benign Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of the Vulva Heller, Debra https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643402930004646?l#13643525330004646 Heller, D. (2015). Benign Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of the Vulva. In Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology (Vol. 58, Issue 3, pp. 526–535). Rutgers University. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3RN3B2N This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/23 14:56:57 -0400 Heller DS Benign Tumors and Tumor-like lesions of the Vulva Debra S. Heller, MD From the Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ Address Correspondence to: Debra S. Heller, MD Dept of Pathology-UH/E158 Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School 185 South Orange Ave Newark, NJ, 07103 Tel 973-972-0751 Fax 973-972-5724 [email protected] Funding: None Disclosures: None 1 Heller DS Abstract: A variety of mass lesions may affect the vulva. These may be non-neoplastic, or represent benign or malignant neoplasms. A review of benign mass lesions and neoplasms of the vulva is presented. Key words: Vulvar neoplasms, vulvar diseases, vulva 2 Heller DS Introduction: A variety of mass lesions may affect the vulva. These may be non-neoplastic, or represent benign or malignant neoplasms. Often an excision is required for both diagnosis and therapy. A review of the more commonly encountered non-neoplastic mass lesions and benign neoplasms of the vulva is presented. -

Network Scan Data

CTEP Protocol No: T-99-0090 CC Protocol No: 01-C-0222 Amendment: J Revised: 4/21/09 IRB Approval Date: A Phase II Randomized, Cross-Over, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor R115777 in Pediatric Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and Progressive Plexiform Neurofibromas Coordinating Center: Pediatric Oncology Branch, NCI Principal Investigator: Brigitte Widemann, M.D.* (POB, NCI) NIH Associate Investigators: Frank M. Balis, M.D. (POB, NCI) Beth Fox, M.D. (POB, NCI) Kathy Warren, M.D. (NOB, NCI) Andy Gillespie, R.N. (ND, CC) Eva Dombi, MD (POB, NCI)** Nalini Jayaprakash, (POB, NCI) Diane Cole, (POB, NCI) Seth Steinberg, Ph.D. (BDMB, DCS, NCI) Nicholas Patronas, M.D. (DR, CC)** Maria Tsokos, M.D., (Laboratory of Pathology, NCI)** Pamela Wolters, Ph.D. (HAMB, NCI) Staci Martin, Ph.D. (HAMB, NCI) Jeffrey Solomon, (NIH and Sensor Systems, Inc.) Non-NIH Associate Investigators: Wanda Salzer, M.D. ** Keesler Air Force Base, Biloxi, Mississippi) 81st MDOS/SGOC 301 Fisher Street, Room 1A132 Keesler AFB, MS 39534-2519 Phone: 228-377-6524 E-mail: [email protected] Bruce R. Korf, M.D., Ph.D. ** Chair, Department of Genetics Univeristy of Alabama at Birmingham 1530 3rd Ave. S. Birmingham, AL 35294 Phone: (205)-934-9411, Fax: (205)-934-9488 E-mail: [email protected] David H. Gutmann, M.D., Ph.D. ** Department of Neurology Washington University School of Medicine St. Louis Children’s Hospital Box 8111, 660 S. Euclid Avenue St. Louis, MO 63110 Phone: (314)-632-7149, Fax: (314)-362-9462 E-mail: [email protected] 1 4/21/2009 T-99-0090, 01-C-0222 Arie Perry, M.D. -

Dermatology DDX Deck, 2Nd Edition 65

63. Herpes simplex (cold sores, fever blisters) PREMALIGNANT AND MALIGNANT NON- 64. Varicella (chicken pox) MELANOMA SKIN TUMORS Dermatology DDX Deck, 2nd Edition 65. Herpes zoster (shingles) 126. Basal cell carcinoma 66. Hand, foot, and mouth disease 127. Actinic keratosis TOPICAL THERAPY 128. Squamous cell carcinoma 1. Basic principles of treatment FUNGAL INFECTIONS 129. Bowen disease 2. Topical corticosteroids 67. Candidiasis (moniliasis) 130. Leukoplakia 68. Candidal balanitis 131. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma ECZEMA 69. Candidiasis (diaper dermatitis) 132. Paget disease of the breast 3. Acute eczematous inflammation 70. Candidiasis of large skin folds (candidal 133. Extramammary Paget disease 4. Rhus dermatitis (poison ivy, poison oak, intertrigo) 134. Cutaneous metastasis poison sumac) 71. Tinea versicolor 5. Subacute eczematous inflammation 72. Tinea of the nails NEVI AND MALIGNANT MELANOMA 6. Chronic eczematous inflammation 73. Angular cheilitis 135. Nevi, melanocytic nevi, moles 7. Lichen simplex chronicus 74. Cutaneous fungal infections (tinea) 136. Atypical mole syndrome (dysplastic nevus 8. Hand eczema 75. Tinea of the foot syndrome) 9. Asteatotic eczema 76. Tinea of the groin 137. Malignant melanoma, lentigo maligna 10. Chapped, fissured feet 77. Tinea of the body 138. Melanoma mimics 11. Allergic contact dermatitis 78. Tinea of the hand 139. Congenital melanocytic nevi 12. Irritant contact dermatitis 79. Tinea incognito 13. Fingertip eczema 80. Tinea of the scalp VASCULAR TUMORS AND MALFORMATIONS 14. Keratolysis exfoliativa 81. Tinea of the beard 140. Hemangiomas of infancy 15. Nummular eczema 141. Vascular malformations 16. Pompholyx EXANTHEMS AND DRUG REACTIONS 142. Cherry angioma 17. Prurigo nodularis 82. Non-specific viral rash 143. Angiokeratoma 18. Stasis dermatitis 83. -

A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta)

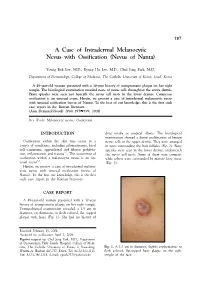

197 A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta) Young Bok Lee, M.D., Kyung Ho Lee, M.D., Chul Jong Park, M.D. Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea A 49-year-old woman presented with a 30-year history of asymptomatic plaque on her right temple. The histological examination revealed nests of nevus cells throughout the entire dermis. Bony spicules were seen just beneath the nevus cell nests in the lower dermis. Cutaneous ossification is an unusual event. Herein, we present a case of intradermal melanocytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. (Ann Dermatol (Seoul) 20(4) 197∼199, 2008) Key Words: Melanocytic nevus, Ossification INTRODUCTION drug intake or medical illness. The histological examination showed a dense proliferation of benign Ossification within the skin may occur in a nevus cells in the upper dermis. They were arranged variety of conditions, including pilomatricoma, basal in nests surrounding the hair follicles (Fig. 2). Bony cell carcinoma, appendageal and fibrous prolifera- spicules were seen in the lower dermis, underneath 1,2 tion, inflammation and trauma . The occurrence of the nevus cell nests. Some of them were compact ossification within a melanocytic nevus is an un- while others were surrounded by mature fatty tissue 3-5 usual event . (Fig. 3). Herein, we present a case of intradermal melano- cytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. -

Melanoma and Other Skin Cancers: a Guide for Medical Practitioners

Melanoma and other skin cancers: a guide for medical practitioners Australia has among the highest rates of skin cancer in Causes of melanoma and • Having fair or red hair and blue or green eyes the world: 2 in 3 Australians will develop some form of other skin cancers • Immune suppression and/or transplant skin cancer before the age of 70 years. • Unprotected exposure to UV radiation remains recipients. the single most important lifestyle risk factor for melanoma and other skin cancers. Gender Skin cancer is divided into two main types: • UVA and UVB radiation contribute to skin In NSW, males are more than 1½ times more damage, premature ageing of the skin and likely to be diagnosed with melanoma and Melanoma Non-melanocytic skin skin cancer. almost 3 times more likely to die from it than Melanoma develops in the melanocytic cancer (NMSC) • Melanoma and BCC are associated with the females (after allowing for differences in age). (pigment-producing) cells located in the amount and pattern of sun exposure, with an • Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) Mortality from melanoma rises steeply for males epidermis. Untreated, melanoma has a high intermittent pattern carrying the highest risk. develops from the keratinocytes in the from 50 years and increases with age. The risk for metastasis. The most common clinical epidermis and is associated with risk • Premalignant actinic keratosis and SCC death rate for males aged: subtype is superficial spreading melanoma of metastasis. SCC is most commonly are associated with the total amount of sun • 50–54 years is twice that of females (SSM). SSM is most commonly found on the found on the face, particularly the lip exposure accumulated over a lifetime. -

Acquired Bilateral Nevus of Ota–Like Macules (Hori's Nevus): a Case

Acquired Bilateral Nevus of Ota–like Macules (Hori’s Nevus): A Case Report and Treatment Update Jamie Hale, DO,* David Dorton, DO,** Kaisa van der Kooi, MD*** *Dermatology Resident, 2nd year, Largo Medical Center/NSUCOM, Largo, FL **Dermatologist, Teaching Faculty, Largo Medical Center/NSUCOM, Largo, FL ***Dermatopathologist, Teaching Faculty, Largo Medical Center/NSUCOM, Largo, FL Abstract This is a case of a 71-year-old African American female who presented with bilateral periorbital hyperpigmentation. After failing treatment with a topical retinoid and hydroquinone, a biopsy was performed and was consistent with acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules, or Hori’s nevus. A review of histopathology, etiology, and treatment is discussed below. cream and tretinoin 0.05% gel. At this visit, a Introduction Figure 2 Acquired nevus of Ota-like macules (ABNOM), punch biopsy of her left zygoma was performed. or Hori’s nevus, clinically presents as bilateral, Histopathology reported sparse proliferation blue-gray to gray-brown macules of the zygomatic of irregularly shaped, haphazardly arranged melanocytes extending from the superficial area. It less often presents on the forehead, upper reticular dermis to mid-deep reticular dermis outer eyelids, and nose.1 It is most common in women of Asian descent and has been reported Figure 4 in ages 20 to 70. Classically, the eye and oral mucosa are uninvolved. This condition is commonly misdiagnosed as melasma.1 The etiology of this condition is not fully understood, and therefore no standardized treatment has been Figure 3 established. Case Report A 71-year-old African American female initially presented with a two week history of a pruritic, flaky rash with discoloration of her face. -

Retinoblastoma Major Review with Updates on Middle East Management Protocols

Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology (2012) 26, 163–175 Ophthalmic Pathology Update Retinoblastoma major review with updates on Middle East management protocols ⇑ Ihab Saad Othman, MD, FRCS Abstract Many advances in the field of management of retinoblastoma emerged in the past few years. Patterns of presentation of retino- blastoma in the Middle East region differ from Western community. The use of enucleation as a radical method of eradicating advanced disease is not easily accepted by patient’s family. We still do see stage E, failed or resistant retinoblastoma and advanced extraocular disease ensues as a result of delayed enucleation decision. In this review, we discuss updates in management of retinoblastoma with its implication on patients in our part of the world. Identifying clinical and high risk characteristics is impor- tant prognostically and are discussed for further management of retinoblastoma cases. Keywords: Retinoblastoma, Staging, Classification, Histopathology, Middle East Ó 2012 Saudi Ophthalmological Society, King Saud University. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjopt.2012.03.002 Introduction cases is 100–120 cases/year.3 In a recent report from Jordan, the mean age-adjusted incidence of retinoblastoma was 9.32 Retinoblastoma is the commonest primary ocular malig- cases per million children per year for children aged 0– nancy of childhood originating from primitive retinoblasts 5 years.4 Retinoblastoma constituted 4.8% of childhood can- with tendency towards cone differentiation. Retinoblasts cer treated over 10 years at the National Cancer Institute in arise from the inner neuroepithelial layers of the embryonic Sudan and presented in an advanced stage in 16 out of 25 re- optic cup.1 The incidence of retinoblastoma ranges from 1/ ported cases.5 15,000 to 1/20,000 live births with an annual incidence in chil- dren younger than 5 years of 10.9/million. -

Diagnostic Distinction of Malignant Melanoma and Benign Nevi by a Gene Expression Signature and Correlation to Clinical Outcomes

Published OnlineFirst April 4, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0958 Research Article Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers Diagnostic Distinction of Malignant Melanoma and & Prevention Benign Nevi by a Gene Expression Signature and Correlation to Clinical Outcomes Jennifer S. Ko1, Balwir Matharoo-Ball2, Steven D. Billings1, Brian J.Thomson2, Jean Y.Tang3, Kavita Y. Sarin3, Emily Cai3, Jinah Kim3, Colleen Rock4, Hillary Z. Kimbrell4, Darl D. Flake II4, M. Bryan Warf4, Jonathan Nelson4, Thaylon Davis4, Catherine Miller4, Kristen Rushton4, Anne-Renee Hartman4, Richard J. Wenstrup4, and Loren E. Clarke4 Abstract Background: Histopathologic examination alone can be inad- were excluded. Benign lesions were defined as cutaneous mela- equate for diagnosis of certain melanocytic neoplasms. Recently, a nocytic lesions with no adverse long-term events reported. 23-gene expression signature was clinically validated as an ancil- Results: Of 239 submitted samples, 182 met inclusion criteria lary diagnostic test to differentiate benign nevi from melanoma. and produced a valid gene expression result. This included 99 The current study assessed the performance of this test in an primary cutaneous melanomas with proven distant metastases independent cohort of melanocytic lesions against clinically and 83 melanocytic nevi. Median time to melanoma metastasis proven outcomes. was 18 months. Median follow-up time for nevi was 74.9 months. Methods: Archival tissue from primary cutaneous melanomas The gene expression score differentiated melanoma from nevi and melanocytic nevi was obtained from four independent insti- with a sensitivity of 93.8% and a specificity of 96.2%. tutions and tested with the gene signature. Cases were selected Conclusions: The results of gene expression testing closely according to pre-defined clinical outcome measures. -

Diagnostic Pitfall of Localized Lentigo Accompanied by Post-Inflammatory

Letter to the Editor Diagnostic pitfall of localized lentigo accompanied by post-inflammatory pigmentation on the palm with a several-month history Keisuke Imafuku, Hiroo Hata, Shinya Kitamura, Toshifumi Nomura, Hiroshi Shimizu Department of Dermatology, Hokkaido University Graduate School of MedicineNorth 15, West 7, Kita-ku, Sapporo 060- 8638, Japan Corresponding author: Dr. Hiroo Hata, MD, PhD, E-mail: [email protected] Sir, When dermatologists see acquired and well- circumscribed pigmented macules on the palm, dorsal hand or forearm of the elderly, they tend to consider blue nevus, hematoma, nevus cell nevus and malignant melanoma as differential diagnoses [1]. We a b herein described the very rare case of localized lentigo Figure 1: Clinical manifestations. a. The macule is brown to dark black, accompanied by post-inflammatory pigmentation well-demarcated, flat, round and 3 x 4 mm in size. b. Dermoscopy of the macule shows homogenous brownish pigmentation without the in a patient who has been treated for palmoplanter parallel ridge or furrow pattern that is commonly observed in acral pustulosis for a long time. This eruption mimicked lentiginous lesion some kinds of lentiginous lesion and it was difficult to diagnose clinically. A 59-year-old female was referred to our hospital with a pigmented macule on her left palm. She had been to the family doctor for treatment of palmoplanter pustulosis by topical steroid ointment application for several years. According to the a history-taking interview, she said that the lesion had b appeared 5 months before referral to our hospital as a tiny pigmented macule and had gradually enlarged during those 5 months (Fig. -

Glaucoma Related to Ocular and Orbital Tumors Sonal P

Chapter Glaucoma Related to Ocular and Orbital Tumors Sonal P. Yadav Abstract Secondary glaucoma due to ocular and orbital tumors can be a diagnostic challenge. It is an essential differential to consider in eyes with a known tumor as well as with unilateral, atypical, asymmetrical, or refractory glaucoma. Various intraocular neoplasms including iris and ciliary body tumors (melanoma, metasta- sis, lymphoma), choroidal tumors (melanoma, metastasis), vitreo-retinal tumors (retinoblastoma, medulloepithelioma, vitreoretinal lymphoma) and orbital tumors (extra-scleral extension of choroidal melanoma or retinoblastoma, primary orbital tumors) etc. can lead to raised intraocular pressure. The mechanisms for glaucoma include direct (tumor invasion or infiltration related outflow obstruction, tra- becular meshwork seeding) or indirect (angle closure from neovascularization or anterior displacement or compression of iris) or elevated episcleral venous pressure secondary to orbital tumors. These forms of glaucoma need unique diagnostic techniques and customized treatment considerations as they often pose therapeutic dilemmas. This chapter will review and discuss the mechanisms, clinical presenta- tions and management of glaucoma related to ocular and orbital tumors. Keywords: ocular tumors, secondary glaucoma, orbital tumors, angle infiltration, neovascular glaucoma, neoplastic glaucoma 1. Introduction With the advent of constantly evolving and advancing ophthalmic imaging tech- niques as well as surgical modalities in the field of ophthalmic diseases, diagnostic accuracy, and treatment outcomes of ocular as well as orbital tumors have improved remarkably over the past few years. Raised intraocular pressure (IOP) is known to be one of the presenting features or associated finding for numerous ocular as well as orbital tumors. Ocular and orbital tumors can cause secondary glaucoma due to various mechanisms. -

Eyelid Conjunctival Tumors

EYELID &CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS PHOTOGRAPHIC ATLAS Dr. Olivier Galatoire Dr. Christine Levy-Gabriel Dr. Mathieu Zmuda EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS 4 EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS Dear readers, All rights of translation, adaptation, or reproduction by any means are reserved in all countries. The reproduction or representation, in whole or in part and by any means, of any of the pages published in the present book without the prior written consent of the publisher, is prohibited and illegal and would constitute an infringement. Only reproductions strictly reserved for the private use of the copier and not intended for collective use, and short analyses and quotations justified by the illustrative or scientific nature of the work in which they are incorporated, are authorized (Law of March 11, 1957 art. 40 and 41 and Criminal Code art. 425). EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS 5 6 EYELID & CONJUNCTIVAL TUMORS Foreword Dr. Serge Morax I am honored to introduce this Photographic Atlas of palpebral and conjunctival tumors,which is the culmination of the close collaboration between Drs. Olivier Galatoire and Mathieu Zmuda of the A. de Rothschild Ophthalmological Foundation and Dr. Christine Levy-Gabriel of the Curie Institute. The subject is now of unquestionable importance and evidently of great interest to Ophthalmologists, whether they are orbital- palpebral specialists or not. Indeed, errors or delays in the diagnosis of tumor pathologies are relatively common and the consequences can be serious in the case of malignant tumors, especially carcinomas. Swift diagnosis and anatomopathological confirmation will lead to a treatment, discussed in multidisciplinary team meetings, ranging from surgery to radiotherapy.