Official Conference Proceedings Acp2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Assessment of Agricultural Affected by Climate Change: Central Region of Thailand

International Journal of Applied Computer Technology and Information Systems: Volume 10, No.1, April 2020 - September 2020 Risk Assessment of Agricultural Affected by Climate Change: Central Region of Thailand Pratueng Vongtong1*, Suwut Tumthong2, Wanna Sripetcharaporn3, Praphat klubnual4, Yuwadee Chomdang5, Wannaporn Suthon6 1*,2,3,4,5,6 Faculty of Science and Technology, Rajamangala University of Technology Suvarnabhumi, Ayutthaya, Thailand e-mail: 1*[email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract — The objective of this study are to create a changing climate, the cultivation of Thai economic risk model of agriculture with the Geo Information crops was considerably affected [2] System (GIS) and calculate the Agricultural In addition, the economic impact of global Vulnerability Index ( AVI) in Chainat, Singburi, Ang climate change on rice production in Thailand was Thong and Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya provinces by assessed [3] on the impact of climate change. The selecting factors from the Likelihood Vulnerability results of assessment indicated that climate change Index (LVI) that were relevant to agriculture and the affected the economic dimension of rice production in climate. The data used in the study were during the year Thailand. Both the quantity of production and income 1986-2016 and determined into three main components of farmers. that each of which has a sub-component namely: This study applied the concept of the (1)Exposure -

Collective Consciousness of Ethnic Groups in the Upper Central Region of Thailand

Collective Consciousness of Ethnic Groups in the Upper Central Region of Thailand Chawitra Tantimala, Chandrakasem Rajabhat University, Thailand The Asian Conference on Psychology & the Behavioral Sciences 2019 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This research aimed to study the memories of the past and the process of constructing collective consciousness of ethnicity in the upper central region of Thailand. The scope of the study has been included ethnic groups in 3 provinces: Lopburi, Chai-nat, and Singburi and 7 groups: Yuan, Mon, Phuan, Lao Vieng, Lao Khrang, Lao Ngaew, and Thai Beung. Qualitative methodology and ethnography approach were deployed on this study. Participant and non-participant observation and semi-structured interview for 7 leaders of each ethnic group were used to collect the data. According to the study, it has been found that these ethnic groups emigrated to Siam or Thailand currently in the late Ayutthaya period to the early Rattanakosin period. They aggregated and started to settle down along the major rivers in the upper central region of Thailand. They brought the traditional beliefs, values, and living style from the motherland; shared a sense of unified ethnicity in common, whereas they did not express to the other society, because once there was Thai-valued movement by the government. However, they continued to convey the wisdom of their ancestors to the younger generations through the stories from memory, way of life, rituals, plays and also the identity of each ethnic group’s fabric. While some groups blend well with the local Thai culture and became a contemporary cultural identity that has been remodeled from the profoundly varied nations. -

4. Counter-Memorial of the Royal Government of Thailand

4. COUNTER-MEMORIAL OF THE ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF THAILAND I. The present dispute concerns the sovereignty over a portion of land on which the temple of Phra Viharn stands. ("PhraViharn", which is the Thai spelling of the name, is used throughout this pleading. "Preah Vihear" is the Cambodian spelling.) 2. According to the Application (par. I), ThaiIand has, since 1949, persisted in the occupation of a portion of Cambodian territory. This accusation is quite unjustified. As will be abundantly demon- strated in the follo~vingpages, the territory in question was Siamese before the Treaty of 1904,was Ieft to Siam by the Treaty and has continued to be considered and treated as such by Thailand without any protest on the part of France or Cambodia until 1949. 3. The Government of Cambodia alleges that its "right can be established from three points of rieivJ' (Application, par. 2). The first of these is said to be "the terms of the international conventions delimiting the frontier between Cambodia and Thailand". More particuIarly, Cambodia has stated in its Application (par. 4, p. 7) that a Treaty of 13th February, 1904 ". is fundamental for the purposes of the settlement of the present dispute". The Government of Thailand agrees that this Treaty is fundamental. It is therefore common ground between the parties that the basic issue before the Court is the appIication or interpretation of that Treaty. It defines the boundary in the area of the temple as the watershed in the Dangrek mountains. The true effect of the Treaty, as will be demonstratcd later, is to put the temple on the Thai side of the frontier. -

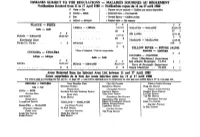

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received Bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications Reçues Du 9 Au 14 Mai 1980 C Cases — Cas

Wkty Epldem. Bec.: No. 20 -16 May 1980 — 150 — Relevé éptdém. hebd : N° 20 - 16 mal 1980 Kano State D elete — Supprimer: Bimi-Kudi : General Hospital Lagos State D elete — Supprimer: Marina: Port Health Office Niger State D elete — Supprimer: Mima: Health Office Bauchi State Insert — Insérer: Tafawa Belewa: Comprehensive Rural Health Centre Insert — Insérer: Borno State (title — titre) Gongola State Insert — Insérer: Garkida: General Hospital Kano State In se rt— Insérer: Bimi-Kudu: General Hospital Lagos State Insert — Insérer: Ikeja: Port Health Office Lagos: Port Health Office Niger State Insert — Insérer: Minna: Health Office Oyo State Insert — Insérer: Ibadan: Jericho Nursing Home Military Hospital Onireke Health Office The Polytechnic Health Centre State Health Office Epidemiological Unit University of Ibadan Health Services Ile-Ife: State Hospital University of Ife Health Centre Ilesha: Health Office Ogbomosho: Baptist Medical Centre Oshogbo : Health Office Oyo: Health Office DISEASES SUBJECT TO THE REGULATIONS — MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications reçues du 9 au 14 mai 1980 C Cases — Cas ... Figures not yet received — Chiffres non encore disponibles D Deaths — Décès / Imported cases — Cas importés P t o n r Revised figures — Chifircs révisés A Airport — Aéroport s Suspect cases — Cas suspects CHOLERA — CHOLÉRA C D YELLOW FEVER — FIÈVRE JAUNE ZAMBIA — ZAMBIE 1-8.V Africa — Afrique Africa — Afrique / 4 0 C 0 C D \ 3r 0 CAMEROON. UNITED REP. OF 7-13JV MOZAMBIQUE 20-26J.V CAMEROUN, RÉP.-UNIE DU 5 2 2 Asia — Asie Cameroun Oriental 13-19.IV C D Diamaré Département N agaba....................... î 1 55 1 BURMA — BIRMANIE 27.1V-3.V Petté ........................... -

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received from 11 to 17 April 1980 — Notifications Reçues Dn 11 Au 17 Avril 1980 C Cases — C As

Wkly Epidem. Rec * No. 16 - 18 April 1980 — 118 — Relevé èpidém, hebd. * N° 16 - 18 avril 1980 investigate neonates who had normal eyes. At the last meeting in lement des yeux. La séné de cas étudiés a donc été triée sur le volet December 1979, it was decided that, as the investigation and follow et aucun effort n’a été fait, dans un stade initial, pour examiner les up system has worked well during 1979, a preliminary incidence nouveau-nés dont les yeux ne présentaient aucune anomalie. A la figure of the Eastern District of Glasgow might be released as soon dernière réunion, au mois de décembre 1979, il a été décidé que le as all 1979 cases had been examined, with a view to helping others système d’enquête et de visites de contrôle ultérieures ayant bien to see the problem in perspective, it was, of course, realized that fonctionné durant l’année 1979, il serait peut-être possible de the Eastern District of Glasgow might not be representative of the communiquer un chiffre préliminaire sur l’incidence de la maladie city, or the country as a whole and that further continuing work dans le quartier est de Glasgow dès que tous les cas notifiés en 1979 might be necessary to establish a long-term and overall incidence auraient été examinés, ce qui aiderait à bien situer le problème. On figure. avait bien entendu conscience que le quartier est de Glasgow n ’est peut-être pas représentatif de la ville, ou de l’ensemble du pays et qu’il pourrait être nécessaire de poursuivre les travaux pour établir le chiffre global et à long terme de l’incidence de ces infections. -

Guidelines for Enhancing the Cultural Tourism Marketing in Singburi

Journal of Community Development Research (Humanities and Social Sciences) 2019; 12(2) Teare, M. D., Dimairo, M., Shephard, N., Hayman, A., Whitehead, A., & Walters, S. J. (2014). Sample Size Guidelines for Enhancing the Cultural Tourism Marketing in Singburi Province Requirements to Estimate Key Design Parameters from External Pilot Randomised Controlled Trials: Sarunporn Chuankrerkul A Simulation Study. Trials, 15(264), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-264 Department of Marketing, Doctor of Business Administration Program, Siam University, Bangkok 10160, Thailand Wiegmann, D. A., & Shappel, S. A. (2003). A Human Error Approach to Aviation Accident Analysis. Burlington: Corresponding author. E-Mail address: [email protected] Ashgate. Received: 19 November 2018; Accepted: 22 January 2019 Wiegmann, D. A., Zhang, H., von Thaden, T. L., Sharma, G., & Gibbons, A. M. (2004). Safety Culture: An Abstract This quantitative research aims to study behavior of Thai tourists in Singburi Province, examine the level of tourist’s satisfaction Integrative Review. The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 14(2), 117–134. and expectation toward cultural tourism marketing in Singburi Province, and give guidelines on enhancing cultural tourism marketing in Singburi Province. Four hundred and two Thai tourists who visited Singburi were selected as the samples of this Williamson, A. M., Feyer, A-M., Cairns, D., & Biancotti, D. (1997). The Development of a Measure of research. The study was conducted through the questionnaire survey which was used as a tool to collect data. The data was analyzed by Safety Climate: the Role of Safety Perceptions and Attitudes. Safety Science, 25(1–3), 15–27. looking at the frequency, percentage, mean and Standard Deviation. -

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received from 14 to 20 March 1980 — Notifications Reçues Du 14 Au 20 Mars 1980

Wkty Epidem. Xec.: No. 12-21 March 1980 — 90 — Relevé êpittém. hetxl. : N° 12 - 21 mars 1980 A minor variant, A/USSR/50/79, was also submitted from Brazil. A/USSR/90/77 par le Brésil. Un variant mineur, A/USSR/50/79, a Among influenza B strains, B/Singapore/222/79-like strains were aussi été soumis par le Brésil. Parmi les souches virales B, des souches submitted from Trinidad and Tobago and B/Hong Kong/5/72-like similaires à B/Singapore/222/79 ont été soumises par la Trimté-et- from Brazil. Tobago et des souches similaires à B/Hong Kong/5/72 par le Brésil. C zechoslovakia (28 February 1980). — *1 The incidence of acute T chécoslovaquie (28 février 1980). — 1 Après la pointe de début respiratory disease in the Czech regions is decreasing after a peak in février 1980, l’incidence des affections respiratoires aigues est en early February 1980. In the Slovakian regions a sharp increase was diminution dans les régions tchèques. Dans les régions slovaques, seen at the end of January but, after a peak at the end of February, the une forte augmentation a été constatée fin janvier mais, après un incidence has been decreasing in all age groups except those 6-14 maximum fin février, l’incidence diminue dans tous les groupes years. All strains isolated from both regions show a relationship d'âge, sauf les 6-14 ans. Toutes les souches isolées dans les deux with A/Texas/1/77 (H3N2) although with some antigenic drift. régions sont apparentées à A/Texas/1/77 (H3N2), mais avec un certain glissement antigénique. -

Thailand, July 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Thailand, July 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: THAILAND July 2007 COUNTRY ั Formal Name: Kingdom of Thailand (Ratcha Anachak Thai). ราชอาณาจกรไทย Short Form: Thailand (Prathet Thai—ประเทศไทย—Land of the Free, or, less formally, Muang Thai—เมืองไทย—also meaning Land of the Free; officially known from 1855 to 1939 and from 1946 to 1949 as Siam—Prathet Sayam, ประเทศสยาม, a historical name referring to people in the Chao Phraya Valley—the name used by Europeans since 1592). Term for Citizen(s): Thai (singular and plural). พลเมือง Capital: Bangkok (in Thai, Krung Thep, กรุงเทพ—City of Angels). Major Cities: The largest metropolitan area is the capital, Bangkok, with an estimated 9.6 million inhabitants in 2002. According to the 2000 Thai census, 6.3 million people were living in the metropolitan area (combining Bangkok and Thon Buri). Other major cities, based on 2000 census data, include Samut Prakan (378,000), Nanthaburi (291,000), Udon Thani (220,000), and Nakhon Ratchasima (204,000). Fifteen other cities had populations of more than 100,000 in 2000. Independence: The traditional founding date is 1238. Unlike other nations in Southeast Asia, Thailand was never colonized. National Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), Makha Bucha Day (Buddhist All Saints Day, movable date in late January to early March), Chakri Day (celebration of the current dynasty, April 6), Songkran Day (New Year’s according to Thai lunar calendar, movable date in April), National Labor Day (May 1), Coronation Day (May 5), Visakha Bucha Day (Triple Anniversary Day—commemorates the birth, death, and enlightenment of Buddha, movable date in May), Asanha Bucha Day (Buddhist Monkhood Day, movable date in July), Khao Phansa (beginning of Buddhist Lent, movable date in July), Queen’s Birthday (August 12), Chulalongkorn Day (birthday of King Rama V, October 23), King’s Birthday—Thailand’s National Day (December 5), Constitution Day (December 10), and New Year’s Eve (December 31). -

President's Message Faculty of Business Administration And

Business Administration National & International Conference 2017 19th December 2017 Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University Publisher Faculty of Business Administration and Management, Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University, Thailand Editor Assoc. Prof. Dr.Piyakanit Chotivanich Editorial Asst. Prof. Hathairat Khuanrudee Faculty of Business Administration and Management, Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University, Thailand Asst. Prof. Ekarat Ekasart Faculty of Management Science, Nakhon Ratchasima Rajabhat University, Thailand Asst. Prof. Dr.Phana Dullayaphut Faculty of Management Science, Udon Thani Rajabhat University, Thailand Asst. Prof. Dr.Kritchana Wongrat Faculty of Management Science, Phetchaburi Rajabhat University, Thailand Asst. Prof. Thanida Poodang Faculty of Management Science, Thepsatri Rajabhat University, Thailand Dr.Padol Amart Faculty of Business Administration and Accounting, Sisaket Rajabhat University, Thailand Dr.Pattariya Prommarat Faculty of Business Administration and Accountancy, Roi Et Rajabhat University, Thailand Dr.Pattanant Petchuedchoo College of Innovative Business and Accountancy, Dhurakij Pundit University, Thailand Dr.Sumalee Ngeoywijit Faculty of Management Science, Ubon Ratchathani University, Thailand Asst. Prof. Kanokon Boonmee. Faculty of Business Administration, North Eastern University, Thailand Prof. Dr.Ghazali Musa Faculty of Business & Accountancy, University of Malaya, Malaysia Mr. Outhay Sidachanh Soudvilay College, Lao PDR Dr.Dian Agustia Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia Dr.Sothan Yoeung University of South-East Asia, Cambodia Published by Faculty of Business Administration and Management, Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University, 2 Ratchathani Road, Muang, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand, 34000 Phone: +66 45 352 000 Ext. 1300, FAX: (045) 355-250 www.bba.ubru.ac.th Email: [email protected] A Peer Review Committee 1. Emeritus Prof. Dr.Lance C. C. Fung Murdoch University, Australia 2. Prof. Dr.Busaya Virakul National Institute of Development Administration, Thailand 3. -

Bangkok Muslims: Social Otherness and Territorial Conceptions

Bangkok Muslims: Social Otherness and Territorial Conceptions Winyu Ardrugsa, PhD Paper presented at the 12th International Conference on Thai Studies 22-24 April 2014 University of Sydney 1 Abstract This paper discusses an alternative history of the Muslims in Bangkok. Rather than providing a mere chronological description, the paper problematises the relationship between social conceptions of the Muslims as the ‘other’ and territorial concepts of the nation and the capital city. The investigation goes through three periods. Before Bangkok was established as the new capital in 1782, in the form of a ‘walled’ city, Muslims had already been called ‘khaek’, a position of the outsiders. During the connected periods of reformation and nationalism between 1850s and 1940s, the Muslims were gradually drawn into the process of assimilation to be ‘thai-isalam’. This followed the emergence of the nation’s ‘bounded’ boundary. After the 1930s, Bangkok Muslims were increasingly associated to the ideological difference between the reformists (khana mai) and traditionalists (khana kao) which was viewed, too simply, as related to the difference between the ‘urban’ and the ‘rural’. The application here is an understanding of the relationship between shifts in the minority’s social status and transformations of Thailand and Bangkok’s spatial conditions not simply as historical facts but as sets of historical constructs. 2 1 Bangkok Muslims: Social Otherness and Territorial Conceptions In 2006 the first documentary focusing on the Muslims of Bangkok was released. The origins of this film, made by three Muslim directors – Panu Aree, Kong Rithdee and Kaweenipon Ketprasit – were significantly driven by the tragic events of 9/11, the recurring southern insurgency in Thailand from 2004 onwards, and the aftermaths of these on the lives of Bangkok Muslims.2 These events were starting points of a crucial period, when the minority must examine its identity against frequently circulating negative images. -

Excavation of a Pre-Dvāravatī Site at Hor-Ek in Ancient Nakhon Pathom

150 Excavation of a Pre-Dvāravatī Site at Hor-Ek in Ancient Nakhon Pathom Saritpong Khunsong, Phasook Indrawooth and Surapol Natapintu ABSTRACT—The ancient city of Nakhon Pathom is the largest Dvāravatī moated site in Central Thailand and has been generally dated to about the seventh to eleventh centuries AD. It has been cited as a capital or a cultural centre of the Dvāravatī period. However, most studies of ancient Nakhon Pathom have taken an art-historical approach, such as Pierre Dupont’s seminal work in 1939–1940 and Piriya Krairiksh’s study of Chula Prathon Chedi in 1975. Basic archaeological study of the cultural stratigraphy in the areas of ancient occupation was conducted only in 1981 with the excavations of Phasook Indrawooth. This article presents the results of archaeological excavation of the Hor-Ek site in 2009 that show evidence of human occupation during circa the third to eleventh centuries AD. The new data from Hor-Ek thus extends the occupational sequence back to a Pre- or Proto-Dvāravatī Period. The Dvāravatī context of ancient Nakhon Pathom While much valuable research on ancient Nakhon Pathom has been published since the time of Rama IV, including the studies of King Rama IV himself (Fine Arts Department 1985), Lucien Fournereau (1895), Lunet de Lajonquière (1912) and Erik Seidenfaden (1929), ancient Nakhon Pathom did not become a well-known Dvāravatī site until publication of the work of Pierre Dupont in L’archéologie mône de Dvāravatī (1959). This landmark study presents an art-historical analysis of Dvāravatī Buddha images and the study of two monuments, Wat Phra Men and Chula Prathon Chedi, which Dupont excavated in 1939 and 1940 in cooperation with the Fine Arts Department. -

Sing Buri 2010 Copyright

Information by: TAT Lop Buri Tourist Information Division (Tel. 0 2250 5500 ext. 2141-5) Designed & Printed by: Promotional Material Production Division, Marketing Services Department. The contents of this publication are subject to change without notice. Sing Buri 2010 Copyright. No commercial reprinting of this material allowed. April 2010 Heroes of Khai Bang Rachan Monument 08.00-20.00 hrs. Everyday Tourist information by fax available 24 hrs. E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.tourismthailand.org cover-JB.indd 1 3/7/11 9:35:23 PM 35 Useful Calls Provincial Public Relations Office Tel: 0 3650 7135 Samut Sakhon Provincial Administration Office Tel: 0 3641 1500 Sing Buri Bus Terrminal Tel: 0 3651 1549 Sing Buri Hospital Tel: 0 3651 1060, 0 3652 1445-8 Tha Chang Hospital Tel: 0 3659 5117, 0 3659 5498 Phrom Buri Hospital Tel: 0 3659 9481, 0 3653 7984 In Buri Hospital Tel: 0 3658 1993-7 Amphoe Mueang Sing Buri Police Station Tel: 0 3651 1213 Highway Police Tel: 0 3651 1416, 1193 Police Tourist Tel: 1155 TAT Tourist Information Centres Tourism Authority of Thailand Head Office 1600 New Phetchaburi Road, Makkasan Ratchathewi, Bangkok 10400 Tel: 0 2250 5500 (120 automatic Lines) Wat Sawang Arom Fax: 0 2250 5511 E-mail: [email protected] Website : www.tourismthailand.org Attractions 6 Amphoe Mueang Sing Buri 6 Ministry of Tourism and Sports 4 Ratchadamnoen Nok Avenue, Bangkok 10100 Amphoe Phrom Buri 12 08.30 a.m.-4.30 p.m. everday Amphoe Tha Chang 14 Amphoe Khai Bang Rachan 15 Tourism Authority of Thailand, Amphoe Bang Rachan 18 Lop Buri Office