Download (3849Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federation to Hold “Conversation with Michael Oren” on Nov. 30

November 6-19, 2020 Published by the Jewish Federation of Greater Binghamton Volume XLIX, Number 36 BINGHAMTON, NEW YORK Federation to hold “Conversation with Michael Oren” on Nov. 30 By Reporter staff said Shelley Hubal, executive “delightful.” Liel Leibovitz, an Oren served as Israel’s ambassador to The Jewish Federation of Greater Bing- director of the Federation. “I Israeli-American journalist and the United States for almost five years hamton will hold a virtual “Conversation look forward to learning how author, wrote that “Oren delivers before becoming a member of Knesset and with Michael Oren” about his new book of he came to write the many sto- a heartfelt and heartbreaking deputy minister in the Prime Minister’s short stories, “The Night Archer and Other ries that appear in his book. I account of who we are as a spe- Office. Oren is a graduate of Princeton Stories,” on Monday, November 30, at would also like to thank Rabbi cies – flawed, fearful, and lonely and Columbia universities. He has been noon. Dora Polachek, associate professor of Barbara Goldman-Wartell for but always open-hearted, always a visiting professor at Harvard, Yale and romance languages and literatures at Bing- alerting us to this opportunity.” trusting that transcendence is Georgetown universities. In addition to hamton University, will moderate. There is Best-selling author Daniel possible, if not imminent.” (For holding four honorary doctorates, he was no cost for the event, but pre-registration Silva called “The Night Archer The Reporter’s review of the awarded the Statesman of the Year Medal is required and can be made at the Feder- and Other Stories” “an extraor- book, see page 4.) by the Washington Institute for Near East ation website, www.jfgb.org. -

Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: the Musical Katherine B

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 "Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The Musical Katherine B. Marcus Reker Scripps College Recommended Citation Marcus Reker, Katherine B., ""Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The usicalM " (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 876. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/876 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CAN WE DO A HAPPY MUSICAL NEXT TIME?”: NAVIGATING BRECHTIAN TRADITION AND SATIRICAL COMEDY THROUGH HOPE’S EYES IN URINETOWN: THE MUSICAL BY KATHERINE MARCUS REKER “Nothing is more revolting than when an actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing.” – Bertolt Brecht SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS GIOVANNI ORTEGA ARTHUR HOROWITZ THOMAS LEABHART RONNIE BROSTERMAN APRIL 22, 2016 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the support of the entire Faculty, Staff, and Community of the Pomona College Department of Theatre and Dance. Thank you to Art, Sherry, Betty, Janet, Gio, Tom, Carolyn, and Joyce for teaching and supporting me throughout this process and my time at Scripps College. Thank you, Art, for convincing me to minor and eventually major in this beautiful subject after taking my first theatre class with you my second year here. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Khurram Shahzad

Contact Khurram Shahzad Mobile : 0321-5231894 Assistant Professor (NUML) e-mail : Citizenship: Pakistani Date of birth : 4th January, 1980 [email protected] [email protected] Research fellowship from the University of North Texas, USA Address H. No. 105/20-C, Awan Street, Shalley Valley, Rawalpindi, Pakistan Profile University teacher with 16 years of experience teaching 18-30 year olds in classroom setting of up to 40 students. An organized professional with proven teaching, guidance and counseling skills. Possess a strong track record in improving test scores and teaching effectively. Ability to be a team player and resolve problems and conflicts professionally. Skilled at communicating complex information in a simple and entertaining manner. Looking to contribute my knowledge and skills in the university that offers a genuine opportunity for career progression. Education 2013 – 2018 (March) Ph D in English (linguistics) from International Islamic University Thesis Title Analyzing English Language Teaching And Testing Praxis In Developing Discourse Competence In Essay Writing 2009 -- 2011 MS / M Phil (linguistics) from International Islamic University Thesis Title 2001-- 2003 Masters in English language & literature from National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad Jan, 2004 – Dec, 2004 B. Ed from National University of Modern Languages August 2000-- 2000 December Diploma in English Language from National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad 1998- 2000 Bachelor’s degree from the Govt. Gordon College, Rawalpindi 1996- -

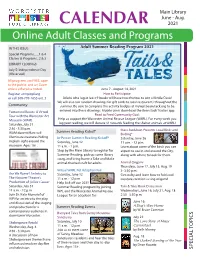

Online Adult Classes and Programs

Main Library June - Aug. CALENDAR 2021 Online Adult Classes and Programs IN THIS ISSUE: Adult Summer Reading Program 2021 Special Programs.......1 & 4 Classes & Programs...2 & 3 LIBRARY CLOSINGS: July 5: Independence Day (Observed) All programs are FREE, open to the public, and on Zoom unless otherwise noted. June 7 - August 14, 2021 Register at mywpl.org How to Participate: or call 508-799-1655 ext. 3 Adults who log at least 9 books will have two chances to win a Kindle Oasis! We will also run random drawings for gift cards to local restaurants throughout the Community summer. Be sure to complete the activity badges at mywpl.beanstack.org to be Fantastical Beasts: A Virtual entered into these drawings. Mobile users download the Beanstack Tracker app. Tour with the Worcester Art Read to Feed Community Goal: Museum (WAM) Help us support the Worcester Animal Rescue League (WARL). For every week you Saturday, July 31 log your reading, we will donate $1 towards feeding the shelter animals at WARL! 2:30 - 3:30 p.m. Summer Reading Kickoff Mass Audubon Presents Local Birds and WAM docent Marc will Birding* illuminate creatures hiding In-Person Summer Reading Kickoff* Saturday, June 26 in plain sight around the Saturday, June 12 11 a.m. - 12 p.m. museum. Ages 16+. 11 a.m. - 1 p.m. Learn about some of the birds you can Stop by the Main Library to register for expect to see in and around the City, Summer Reading, pick up some library along with where to look for them. -

Daniyal Mueenuddin's in Other Rooms, Other Wonders Reviewed

Pakistaniaat: A Journal of Pakistan Studies Vol. 2, No. 1 (2010) Daniyal Mueenuddin’s In Other Rooms, Other Wonders Reviewed by Sohomjit Ray In Other Rooms, Other Wonders. Daniyal Mueenuddin. New York: W. W. Norton, 2009. 247 pages. ISBN: 978-0-393-06800-9. Should Daniyal Mueenuddin’s debut collection of short stories, In Other Rooms, Other Wonders (2009) be considered a part of Pakistani literature, or should it be considered a part of the American literary landscape, already so enriched by the writers of South Asian diaspora? Salman Rushdie’s inclusion of the first story in the collection (“Nawabdin Electrician”) in the anthology entitled “Best American Short Stories 2008” by no means settles the question, but provides a useful frame in which to discuss it. The consideration of the question of nationality with regards to literature (it is fully debatable whether such a thing can be said to exist, although that debate is well beyond the scope of this review), of course, generates another very pertinent one: is the question important at all? In response to the latter ques- tion, one needs only to look at the reviews of the book published in a few of the renowned American newspapers to realize that the question is important, and also why. Dalia Sofer notes in her review of the book in The New York Times that “women in these stories often use sex to prey on the men, and they do so with aban- don at best and rage at worst — in this patriarchal, hierarchical society, it is their sharpest weapon” and that “the women are not alone in their scheming. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

A Linguistic Critique of Pakistani-American Fiction

CULTURAL AND IDEOLOGICAL REPRESENTATIONS THROUGH PAKISTANIZATION OF ENGLISH: A LINGUISTIC CRITIQUE OF PAKISTANI-AMERICAN FICTION By Supervisor Muhammad Sheeraz Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan 47-FLL/PHDENG/F10 Assistant Professor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English To DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD April 2014 ii iii iv To my Ama & Abba (who dream and pray; I live) v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I owe special gratitude to my teacher and research supervisor, Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan. His spirit of adventure in research, the originality of his ideas in regard to analysis, and the substance of his intellect in teaching have guided, inspired and helped me throughout this project. Special thanks are due to Dr. Kira Hall for having mentored my research works since 2008, particularly for her guidance during my research at Colorado University at Boulder. I express my deepest appreciation to Mr. Raza Ali Hasan, the warmth of whose company made my stay in Boulder very productive and a memorable one. I would also like to thank Dr. Munawar Iqbal Ahmad Gondal, Chairman Department of English, and Dean FLL, IIUI, for his persistent support all these years. I am very grateful to my honorable teachers Dr. Raja Naseem Akhter and Dr. Ayaz Afsar, and colleague friends Mr. Shahbaz Malik, Mr. Muhammad Hussain, Mr. Muhammad Ali, and Mr. Rizwan Aftab. I am thankful to my friends Dr. Abdul Aziz Sahir, Dr. Abdullah Jan Abid, Mr. Muhammad Awais Bin Wasi, Mr. Muhammad Ilyas Chishti, Mr. Shahid Abbas and Mr. -

Politics in Fictional Entertainment: an Empirical Classification of Movies and TV Series

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OPUS Augsburg International Journal of Communication 9(2015), 1563–1587 1932–8036/20150005 Politics in Fictional Entertainment: An Empirical Classification of Movies and TV Series CHRISTIANE EILDERS CORDULA NITSCH University of Duesseldorf, Germany This article presents conceptual considerations on the classification of TV series and movies according to their political references and introduces an empirical approach for measuring the constituent features. We argue that political representations in fiction vary along two dimensions: political intensity and degree of realism. These dimensions encompass four indicators relating to characters, places, themes, and time. The indicators were coded for a sample of 98 TV series and 114 movies. Cluster analyses showed four clusters of TV series and six clusters of movies. Nonpolitical fiction, thrillers, and fantasy were central types in both TV series and movies. Movies, however, stand out through a greater diversity and a focus on the past that is reflected in three additional types. Based on the identification of different types of movies and TV series, three directions for theory building are suggested. Keywords: fictional entertainment, TV series, movies, classification, political intensity, degree of realism As the lines between information and entertainment become increasingly blurred, scholarly attention is not only directed to entertainment features in information programs but extends to information in entertainment programs. The latter especially regards the pictures of reality that are constructed in the respective programs. Attention is directed to both the identification of such pictures and the assessment of their possible effects. -

How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-17-2017 2:00 PM Terrorism, Islamization, and Human Rights: How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World Shazia Sadaf The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Julia Emberley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Shazia Sadaf 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons Recommended Citation Sadaf, Shazia, "Terrorism, Islamization, and Human Rights: How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5055. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5055 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Terrorism, Islamization, and Human Rights: How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World Abstract The start of the twenty-first century has witnessed a simultaneous rise of three areas of scholarly interest: 9/11 literature, human rights discourse, and War on Terror studies. The resulting intersections between literature and human rights, foregrounded by an overarching narrative of terror, have led to a new area of interdisciplinary enquiry broadly classed under human rights literature, at the point of the convergence of which lies the idea of human empathy. -

Motown the Musical

LINKS 2017/2018 LINKS 2017/2018 INTRODUCTION Hancher Links is a guide for University of Iowa faculty and staff, highlighting connections between Hancher performances and college courses. You’ll see themes listed with each show that may be relevant to a variety of classes across disciplines. There are a number of ways to integrate Hancher into your class: • Assign performances and public education programs as enrichment activities for students • Set up a class visit or workshops with artists or Hancher staff • Develop a student service learning course or unit around a Hancher project • Hancher can provide readings, videos, and other resources to contextualize an artist or performance A number of faculty members have students purchase Hancher tickets as part of their course materials similar to a required textbook. If you are interested in holding a block of tickets for purchase by the students in your class, contact the Hancher Box Office at (319) 335-1160 or 800-HANCHER. Ask for Leslie or Elizabeth to reserve tickets. Prices and other ticketing information can be found on our website at hancher.uiowa.edu or by contacting the box office. Please feel free to contact me to explore the possibility of bringing an artist to your class or if you have ideas about how you or your department can partner with Hancher. Thanks! Micah Ariel James Education Manager Hancher | The University of Iowa [email protected] (319) 335-0009 hancher.uiowa.edu 2 LINKS 2017/2018 HANCHER ARTIST RESIDENCIES Hancher is committed to connecting artists with audiences beyond the stage. Hancher residencies bring artists to campus, into the community, and across the state.