You're an Orphan When Science Fiction Raises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress Report #1

Welcome to the first progress report for the 2021 World Fantasy Convention! We are pressing on, in times of Covid, and continuing to plan a wonderful in person convention in Montréal, Canada. We have a stunning guest list and a superlative team for both planning and the creation of the gathering not to be missed. We will be at the Hôtel Bonaventure, an iconic landmark in the city. The hotel is located in the heart of downtown and just outside the Old Port of Montréal. It is near major roads, right across the street from Gare Centrale, the Montréal train station, and is directly connected to two Metro stations, making it easily accessible for both motorists and public transport users. We will be able to enjoy a lavish 2.5 acres of gardens with streams inhabited by ducks and fish as well as a year-round outdoor heated pool. Our committee is busy excitedly planning a convention that will surpass your every expectation. Our theme will be YA fantasy. The field of young adult fantasy has grown from being popular to becoming a dominant category of 21st century literature, bringing millions of new readers to hundreds of new authors. We are working on a diverse program that will explore this genre that celebrates fantasy fiction in all of its forms: epic, dark, paranormal, urban, and other varieties. We invite members to share what they enjoy, what they have learned, what they have written themselves, and what they hope to see coming in the field of young adult fantasy fiction. We look forward to seeing you all in Montréal! Diane Lacey Chair Diversity Statement The committee for the 2021 World Fantasy Convention is unconditionally devoted to promoting diversity within our convention. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

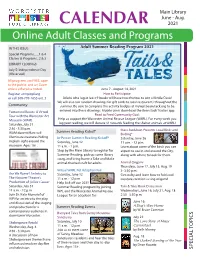

Online Adult Classes and Programs

Main Library June - Aug. CALENDAR 2021 Online Adult Classes and Programs IN THIS ISSUE: Adult Summer Reading Program 2021 Special Programs.......1 & 4 Classes & Programs...2 & 3 LIBRARY CLOSINGS: July 5: Independence Day (Observed) All programs are FREE, open to the public, and on Zoom unless otherwise noted. June 7 - August 14, 2021 Register at mywpl.org How to Participate: or call 508-799-1655 ext. 3 Adults who log at least 9 books will have two chances to win a Kindle Oasis! We will also run random drawings for gift cards to local restaurants throughout the Community summer. Be sure to complete the activity badges at mywpl.beanstack.org to be Fantastical Beasts: A Virtual entered into these drawings. Mobile users download the Beanstack Tracker app. Tour with the Worcester Art Read to Feed Community Goal: Museum (WAM) Help us support the Worcester Animal Rescue League (WARL). For every week you Saturday, July 31 log your reading, we will donate $1 towards feeding the shelter animals at WARL! 2:30 - 3:30 p.m. Summer Reading Kickoff Mass Audubon Presents Local Birds and WAM docent Marc will Birding* illuminate creatures hiding In-Person Summer Reading Kickoff* Saturday, June 26 in plain sight around the Saturday, June 12 11 a.m. - 12 p.m. museum. Ages 16+. 11 a.m. - 1 p.m. Learn about some of the birds you can Stop by the Main Library to register for expect to see in and around the City, Summer Reading, pick up some library along with where to look for them. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

TITLE AUTHOR SUBJECTS Adult Fiction Book Discussion Kits

Adult Fiction Book Discussion Kits Book Discussion Kits are designed for book clubs and other groups to read and discuss the same book. The kits include multiple copies of the book and a discussion guide. Some kits include Large Print copies (noted below in the subject area). Additional Large Print, CDbooks or DVDs may be added upon request, if available. The kit is checked out to one group member who is responsible for all the materials. Book Discussion Kits can be reserved in advance by calling the Adult Services Department, 314-994-3300 ext 2030. Kits may be picked up at any SLCL location, and should be returned inside the branch during normal business hours. To check out a kit, you’ll need a valid SLCL card. Kits are checked out for up to 8 weeks, and may not be renewed. Up to two kits may be checked out at one time to an individual. Customers will not receive a phone call or email when the kit is ready for pick up, so please note the pickup date requested. To search within this list when viewing it on a computer, press the Ctrl and F keys simultaneously, then type your search term (author, title, or subject) into the search box and press Enter. Use the arrow keys next to the search box to navigate to the matches. For a full plot summary, please click on the title, which links to the library catalog. New Book Discussion Kits are in bold red font, updated 11/19. TITLE AUTHOR SUBJECTS 1984 George Orwell science fiction/dystopias/totalitarianism Accident Chris Pavone suspense/spies/assassins/publishing/manuscripts/Large Print historical/women -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Ray Bradbury Has Inspired Generations of Readers to Dream, BUBONICON FRIEND AMONG Think and Create," the Statement Said

ASFACTS 2012 JULY “S UMMER RAINS , S TUPID DRAINS ” I SSUE ROGERS & D ENNING HOSTING PRE -CON PARTY Patricia Rogers and Scott Denning will uphold a local fannish tradition when they host the Bubonicon 44 Pre-Con Party 7:30-10:30 pm Thursday, August 23, at their home in Bernalillo – located at 909 Highway 313. The easiest way to reach the house is north on I-25 to exit 242 east (Rio Rancho’s backdoor and the road to Cuba). At Highway 313, turn right to head north. Look Martian Chronicles and Something Wicked This Way for the Country Store, the John Deere sign and Mile Comes , died June 5 after a lengthy illness. He was 91 Marker 9. Their house is on the west side of the road, with years old. plenty of parking on the shoulder. Bradbury "died peacefully [in the] night, in Los An- In addition to socializing, attendees can help assem- geles, after a lengthy illness," his publisher, Harper- ble the membership packets, and check out the 2012 con t Collins, said in a written statement. -shirt with artwork by Ursula Vernon. Bradbury's books and 600 short stories predicted a Please bring snacks and drinks to share, plus plates, variety of things, including the emergence of ATMs and napkins, cups and some ice. As with any hosted party, live broadcasts of fugitive car chases. please help keep the house clean and in good shape! "In a career spanning more than 70 years, Ray Bradbury has inspired generations of readers to dream, BUBONICON FRIEND AMONG think and create," the statement said. -

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW SFR INTERVIEWS $I-25 Jmy Poumelle ALIEN THOUGHTS Reject up to 10? of the Completed Mss

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW SFR INTERVIEWS $i-25 Jmy Poumelle ALIEN THOUGHTS reject up to 10? of the completed mss. he has contracted for. This is an expensive NOTE FROM W. G. BLISS luxury. Because it is unlikely that any 'JUST HEARD RATHER BELATEDLY THAT AN editor or publisher is going to casually OLD FRIEND AND CORRESPONDENT, RICHARD throw away thousands of dollars in advance S. SHAVER, DIED ON THE 5tt OF NOVEMBER money; rejecting a manuscript under penalty AT THE AGE OF 68. OUTSIDE OF A LARGE of losing or tying up a bundle of cash is LITERARY LEGACY (PALMER HAS KEPT I RE¬ not a happy thing to do. Editors don't MEMBER LEMURIA IN PRINT), HIS MOST IM¬ last long if they have that habit, and pub¬ PORTANT WORK WAS WITH ROCK IMAGES.' lishers who do it or allow it too often end up in bankrupcy court. Because—let's face it: how often will a publisher actually be paid back his ad¬ You probably noticed, as you flipped vance money even if the manuscript is later through this issue before settling down to Not all publishers are ogres... sold to another publisher with perhaps low¬ read this section: no heavy cover, and no And not all writers are saints. er editorial standards who pays less money advertising. even if the later sale is discovered? The So why no cover and ads? It has come to my attention (I get let¬ publisher of the first part is faced with ters, I get phone calls) that some major having to probably sue an author who prob- The cover first: I didn't think the hardcover and pocketbook publishers are now ablt hasn't the money to give back in any cover for SFR 15 would cost as much as it inserting into their contracts with authors event, having spent the second publisher's did. -

Speculative Fiction Studies

Speculative Fiction Studies “The forceps of our mind are clumsy forceps, and crush the truth a little in taking hold of it.” - H.G. Wells Course Description: Speculative Fiction Studies explores and illuminates a genre apart from, and in some ways broader than, the traditional canon of literary fiction. The goal of this course is to explore in what sense the act of “speculation” is central to all literature, but particularly crucial to this genre, which encompasses what we recognize today as fantasy and science fiction as well as alternative histories and futures, utopias and dystopias. Students will explore the evolution of this lively, diverse genre, and consider how its themes and tropes act as allegories for the problems of the human condition. The course will focus on a variety of short- and long-form readings, with class discussion, individual and group projects, analytical writing, speculative writing, and finally research writing as the avenues of assessment. Students will also be presented with scholarship and literary theory in the field of speculative fiction, the better to understand the deep philosophical, literary, and cultural implications of this genre. INSTRUCTOR: • Tracy Townsend • A115C, on campus from 9:30-4:30 A through D days and by appointment. • 630.907.5954 • [email protected] Meeting Days, Time and Room(s) 9:00-9:55 A, C, D (A116) 1:20-2:15 A, C, D (A116) Text(s) / Materials: You will be expected to bring your current readings (critical essays, short stories, and novellas), whether in paper or .pdf form, to class, and your copies of our core texts as we read and discuss them. -

The Novelist As Engineer

The Novelist as Engineer A thesis on credible engineering components of fiction novels (supplemented by an “engineering” fiction novel) by D R Stevens for the Masters Degree in Engineering (Hons) 2007 University of Western Sydney Dedication This thesis is dedicated to Professor Steven Riley who inspired the writing of the thesis in the first place and provided encouragement when motivation waned. Acknowledgement I acknowledge the assistance of Professor Steven Riley, Professor of Research, School of Engineering, University of Western Sydney. I also acknowledge Professor Leon Cantrell who gave significant and important advice particularly on the development of the supplementary novel, (called by the new genre name En-Fi) the title of which is “Amber Reins Fall”. Thanks also go to Dr Stephen Treloar, CEO of Cumberland Industries Limited, where I am the Director of Marketing and Social Enterprises. His contribution is through the scarce resource of time the company allowed me to formulate this thesis. Finally the thesis is dedicated in no small part to Caroline Shindlair who helped tremendously with the typing and construction of the actual documentation. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, is original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. (Signature) Table of Contents Abbreviations Page ................................................................................................ -

1. Hello Jo, Welcome to Fantasy Planet and Thanks a Lot for Doing the Interview

1. Hello Jo, welcome to Fantasy Planet and thanks a lot for doing the interview. I read “Among Others” in a sitting. It was like travelling in a different dimension: I used to overlook Science-fiction in favour of Fantasy and as a result now I have an infinite list of scifi books to read! I empathized with Mori so much, when I was a teenager I used to be exactly like her and this was so touching for me, it was like reading my own secret diary! At this point, I'd like to ask you: how much is there of the Jo Walton teenager in Mori? Lots. With this book I mythologised a part of my own life. 2. In “Among Others” the power of books is enormous: books allow you to meet other people, they can comfort or keep company with you (Mori starts to express interest for her father, for her grandpa, for her first love just thanks to books). Now is this the real magic to you? Are books the real amulets? In real life, magic only works inside your head. So yes, the transformative power of books is real, because they reach into your head and change you. 3. “Among Others” is classified as fantasy or self-knowledge but, above all, it is an amazing novel. Is it delivering the basic concept that amazing books are essential for human development? There are people who seem to grow up just fine without books. But then there are the rest of us. One of the things I didn't realise before I published Among Others is how many people would identify with that aspect of the character. -

Page 1 CATALOG SECTION -1 a B C D E F G H I J K L M N O

CATALOG SECTION -1 ABCD EFG H I JKLMN OPQR STU 0 VWX Y Z 9 1 www.lendingelibrary.tripod.com SECTION -2 TITLES PAGE NO. (EBOOKS) HARRY POTTER 1-6 (EBOOKS) THE COMPLETE CONSPIRACY - 89 EBOOKS 3 BEGINNER DRAWING EBOOKS 3 EBOOKS FOR MAKING CASH 12 HYPNOSIS EBOOKS 15,000+EBOOKS+AUTOMATION 20 ENGLISH-LEARNING EBOOKS 22 EBOOKS ON JOBS RESUMES INTERVIEWS 24 ISLAMIC EBOOKS BY FISABILILLAH PUBLICATIONS 32 FOREX EBOOKS COLLECTION 43 UML AND MDA EBOOKS AND SEVERAL TUTORIALS 32 MUST HAVE HACKERS EBOOKS 49 HEALTH EBOOKS - INC SEX - SMOKING - SKIN – HAIR 57 COOKING E-BOOKS 70 SEXUAL E-BOOKS 82 NEW EBOOKS WITH RESALE 98 DOT NET EBOOKS 126_ORACLE_BOOKS(GREATEST_COLLECTION) 181 EBOOKS ON HEALTH,PERSONAL FINANCE,NUTRITION EDUCATION, ETC A BATCH OF PHYSICS EBOOKS (MECHANICS, QUANTUM, CHEMISTRY, THERMODYNAMICS,), PROBLEMS AND FORMULAS A COLLECTION OF 155 BUSINESS EBOOKS 2 www.lendingelibrary.tripod.com A FEW ENCYCLOPEDIAS A_COLLECTION_OF_FITNESS,_WEIGHTLIFTING,_STRETCHING_EBOOKS ADOBE CS2 EBOOKS ALEISTER CROWLEY RARE COLLECTION AMAZING_PALMISTRY_SECRETS ANNE RICE ARIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE A-Z NON-FICTION BIOTECNOLOGIE EBOOKS PACK2 BIOTECNOLOGIE EBOOKS PACK7 BOOKS[MATHCAD,ANSYS,SOLIDEDGE] BOOKS-MATHS BOTANY EBOOKS CHESS EBOOKS CHESS PROBLEMS & STUDIES BY SUPERKASP CHILDCARE CIRCUITS COMICS COLLECTIONS VOL-1,2,3,4 CISCO REFERENCE SUITE COMICS-ADVENTURES OF TINTIN-THE COMPLETE COLLECTON OF TINTIN- EBOOKS COMPLETE HOME - HOW TO GUIDES 158IN1 (AIO) - EBOOK PDF - DO IT YOURSELF GUIDES COMPTIA A+ CERTIFICATION EBOOKS COMPUTER EBOOKS CD 3 www.lendingelibrary.tripod.com