Shine Bright LLCE Cycle Terminal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

![Billy Elliot the Musical: Visual Representations of Working-Class Masculinity and the All-Singing, All-Dancing Bo[D]Y](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2054/billy-elliot-the-musical-visual-representations-of-working-class-masculinity-and-the-all-singing-all-dancing-bo-d-y-1312054.webp)

Billy Elliot the Musical: Visual Representations of Working-Class Masculinity and the All-Singing, All-Dancing Bo[D]Y

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a paper published in Studies in Musical Theatre. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10354/ Published paper Rodosthenous, George (2007) Billy Elliot The Musical: visual representations of working-class masculinity and the all-singing, all-dancing bo[d]y. Studies in Musical Theatre , 1 (3). pp. 275-292. White Rose Research Online [email protected] ARTICLE NAME Billy Elliot The Musical: Visual representations of working-class masculinity and the all-singing, all-dancing bo[d]y. AUTHOR NAME GEORGE RODOSTHENOUS ABSTRACT According to Cynthia Weber, „[d]ance is commonly thought of as liberating, transformative, empowering, transgressive, and even as dangerous‟. Yet, ballet as a masculine activity, it still remains a suspect phenomenon. This paper will challenge this claim in relation to Billy Elliot the Musical and its critical reception. The transformation of the visual representation of the human body on stage (from an ephemeral existence to a timeless work of art) will be discussed and analysed vis-a-vis the text and sub-texts of Stephen Daldry's direction and Peter Darling‟s choreography. The dynamics of working-class masculinity will be contextualised within the framework of the family, the older female, the community, the self and the act of dancing itself. KEYWORDS Billy Elliot, masculinity, male dancers, dancing musicals, representations of the male AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY George Rodosthenous is Lecturer in Music Theatre at the School of Performance and Cultural Industries of the University of Leeds. -

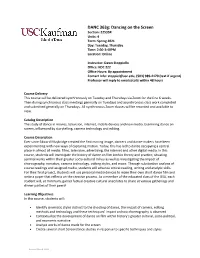

DANC 363G Syllabus S21

DANC 363g: Dancing on the Screen Section: 22535R Units: 4 Term: Spring 2021 Day: Tuesday, Thursday Time: 2:00-3:40PM Location: Online Instructor: Dawn Stoppiello Office: KDC 222 Office Hours: By appointment Contact Info: [email protected], (503) 989-4170 (text if urgent) Professor will reply to emails/calls within 48 hours Course Delivery This course will be delivered synchronously on Tuesday and Thursdays via Zoom for the first 6 weeks. Then during synchronous class meetings generally on Tuesdays and asynchronous class work completed and submitted generally on Thursdays. All synchronous Zoom classes will be recorded and available to view. Catalog Description The study of dance in movies, television, internet, mobile devices and new media. Examining dance on screen, influenced by storytelling, camera technology and editing. Course Description Ever since Edward Muybridge created the first moving image, dancers and dance-makers have been experimenting with new ways of capturing motion. Today, this has led to dance occupying a central place in almost all media: films, television, advertising, the internet and other digital media. In this course, students will investigate the history of dance on film both in theory and practice, situating seminal works within their greater socio-cultural milieu as well as investigating the impact of choreography, narrative, camera technology, editing styles, and music. Through substantive analysis of course readings and assigned media, students will advance critical reading, writing and analytic skills. For their final project, students will use personal media devices to make their own short dance film and write a paper that reflects on the creative process. -

Billy Elliot

LEVEL 3 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme Billy Elliot Melvin Burgess Chapter 6: Billy visits his friend, Michael, who is wearing his sister’s clothes and lipstick. Billy tells Michael that he wants to be a ballet dancer in London. They both realise that they are different from the other boys of their age in their town. Chapter 7: Billy starts practising for a ballet audition and gets very nervous as it gets closer. Jackie and Tony have a fight and Tony runs away. One night Billy sees his dead mother, Sarah, and feels that she wants him to dance at the audition. Chapter 8: Tony attacks a policeman’s horse and ends up in jail. Jackie and Billy go to court to fetch him and Billy misses his audition. Mrs Wilkinson gets furious and tells the Elliots what has happened. Tony can’t believe that his brother wants to be a ballet dancer. About the author Billy Elliot is originally a British film (2000) directed by Chapter 9: Michael, in a dancing skirt, and Billy, in his ballet Stephen Daldry. The screenplay was written by Lee Hall shoes, stand in the boxing ring. While Billy is showing his and then adapted as a novel by Melvin Burgess, who is a friend some ballet moves, his father enters the hall and popular and prolific writer of young adult fiction. Some of sees them. Billy jumps, spins and dances for his father, his works are Junk, Bloodtide and Doing It. who leaves the hall upset but very surprised with what he has seen. -

Drama Movies

Libraries DRAMA MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 42 DVD-5254 12 DVD-1200 70's DVD-0418 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 8 1/2 DVD-3832 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 127 Hours DVD-8008 8 Mile DVD-1639 1776 DVD-0397 9th Company DVD-1383 1900 DVD-4443 About Schmidt DVD-9630 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Accused DVD-6182 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 1 Ace in the Hole DVD-9473 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1 Across the Universe DVD-5997 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adam Bede DVD-7149 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adjustment Bureau DVD-9591 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1 Admiral DVD-7558 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 5 Adventures of Don Juan DVD-2916 25th Hour DVD-2291 Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert DVD-4365 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 Advise and Consent DVD-1514 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 Affair to Remember DVD-1201 3 Women DVD-4850 After Hours DVD-3053 35 Shots of Rum c.2 DVD-4729 c.2 Against All Odds DVD-8241 400 Blows DVD-0336 Age of Consent (Michael Powell) DVD-4779 DVD-8362 Age of Innocence DVD-6179 8/30/2019 Age of Innocence c.2 DVD-6179 c.2 All the King's Men DVD-3291 Agony and the Ecstasy DVD-3308 DVD-9634 Aguirre: The Wrath of God DVD-4816 All the Mornings of the World DVD-1274 Aladin (Bollywood) DVD-6178 All the President's Men DVD-8371 Alexander Nevsky DVD-4983 Amadeus DVD-0099 Alfie DVD-9492 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Amarcord DVD-4426 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul c.2 DVD-4725 c.2 Amazing Dr. -

Geography. a Level Preparation Pack

geography. A Level Preparation Pack Overview The Geography department looks forward to familiarise yourself with over the next few to welcoming you in September. We have months to help you make the transition to A an experienced teacher of Geography who level. will help you make the transition to the much greater demands of A level Geography and give you a lifelong love of the subject. We have collated a range of resources for you Claire Morgan Head of Geography What is Geography? The course is split into Human and Physical Geography and you will study 3 topics in each. Human Geography Global systems and Global Governance: Documentaries • Rotten (Netflix documentary) • Capitalism: A Love Story, Michael Moore (2009) Changing Places: Films • The Full Monty, Peter Cattaneo (1997) • Billy Elliot, Stephen Daldry (2000) • Brassed Off, Mark Herman (1996) • There Will Be Blood, Paul Thomas Anderson (2007) • 8 Mile, Curtis Hanson (2002) Websites • www.datashine.org.uk • https://www.gov.org.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2015 Population and the Environment: Documentaries • No Sex Please We’re Japanese – BBC Two • Megacities – BBC One • Planet Earth – David Attenborough • Our Planet – David Attenborough • Global Population Growth, Box by Box. – Hans Rosling Gapminder Films • Slumdog Millionaire, Danny Boyle (2008) Books • Guns, Germs and Steel, the Fates of Human Societies – Jared Diamond. Physical Geography Water and Carbon Cycles: Documentaries • Chasing Coral (Netflix documentary) • The Fate of Carbon, Changing Seas - Season 9, Episode 3 • The Disarming Case to Act Right Now, Climate Change – Greta Thunberg, Ted Talk. • Before the Flood – Leonardo DiCaprio • An Inconvenient Truth – Al Gore • An Inconvenient Sequel – Al Gore Book • No One Is Too Small To Make A Difference – Greta Thunberg Coastal systems and landscapes: Documentaries. -

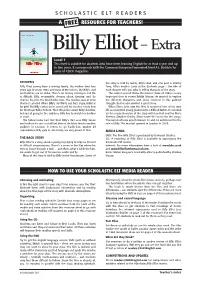

Billy Elliot– Extra

S CHOLASTIC ELT READERS A FREE RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS! Billy Elliot – Extra Level 1 This level is suitable for students who have been learning English for at least a year and up to two years. It corresponds with the Common European Framework level A1. Suitable for users of CLICK magazine. SYNOPSIS the story is told by Jackie, Billy’s dad, and one part is told by Billy Elliot comes from a mining family. His mother died two Tony, Billy’s brother. Look at the Contents page – the title of years ago. It’s now 1984, and most of the miners, like Billy’s dad each chapter tells you who is telling that part of the story. and brother, are on strike. There’s no money coming in and life The writer Lee Hall thinks the miners’ strike of 1984 is a very is difficult. Billy, meanwhile, dreams about dancing, and, by important time in recent British history. He wanted to explore chance, he joins the local ballet class. The teacher sees at once the different characters and ideas involved in this political that he’s special. When Billy’s dad finds out, he’s angry. Ballet is struggle. But he also wanted a good story. for girls! But Billy carries on in secret and his teacher enters him When Elton John saw the film, it reminded him of his own for the Royal Ballet School. Then the police arrest Billy’s brother. life as a talented young pianist with a difficult father. He worked Instead of going to the audition, Billy has to watch his brother on the musical version of the story with Lee Hall and the film’s in court. -

Teaching Diversity with Film

Teaching Diversity with Film The Illinois and United States Constitutions guarantee that all people are to be treated as equals under the law. A wide range of anti-discrimination laws protect people including specific provisions against discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, age, sex, marital status, disability, sexual orientation, military service or unfavorable discharge from military service. These laws extend protections to everyone in our increasingly diverse nation. We can be proud that our equal rights laws and acceptance of diversity stands as an example to other governments and societies. To enhance diversity discussions in classrooms and communities, here is a partial list of films that can be used as tools to generate discussions. Please note: Some have adult content. Teachers should review a selected movie before using in class. A Day Without A Mexican A Patch of Blue A Time to Kill Akeelah and the Bee Amistad Babe Beauty and the Beast Bend it like Beckham Billy Elliot Birth of a Nation Boys Don’t Cry Boyz 'N the Hood Brokeback Mountain Crash Dances With Wolves David and Lisa Do the Right Thing Fried Green Tomatoes Gandhi Ghosts of Mississippi Glory Hiroshima Maiden In the Heat of the Night Malcolm X Mississippi Burning Monsoon Wedding Munich My Left Foot Osama Patch Adams Philadelphia Pokahontas Radio Rain Man Real Women have Curves Remember the Titans Roots Save the Last Dance Schildler’s List Shrek Snow White Sophie’s Choice Spanglish The Color Purple The Gods Must Be Crazy The Hiding Place The Joy Luck Club Thumbelina To Kill a Mockingbird Transamerica West Side Story Wizard of Oz Young Frankenstein Visit the ABA for more diversity film titles http://www.abanet.org/publiced/resources/diversity_ae.html DIVERSITY MOVIE REVIEW ACTIVITY - View one of the movies on the list provided and write a brief review. -

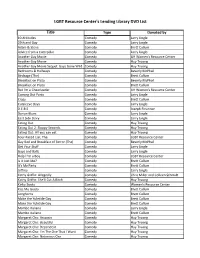

LGBT Resource Center's Lending Library DVD List

LGBT Resource Center's Lending Library DVD List Title Type Donated by 10 Attitudes Comedy Larry Lingle 29th and Gay Comedy Larry Lingle Adam & Steve Comedy Brett Cullum Advice from a Caterpillar Comedy Larry Lingle Another Gay Movie Comedy UH Women's Resource Center Another Gay Movie Comedy Huy Truong Another Gay Movie Sequel: Gays Gone Wild Comedy Huy Truong Bedrooms & Hallways Comedy Beverly McPhail Birdcage (The) Comedy Brett Cullum Breakfast on Pluto Comedy Beverly McPhail Breakfast on Pluto Comedy Brett Cullum But I'm a Cheerleader Comedy UH Women's Resource Center Coming Out Party Comedy Larry Lingle Crazy Comedy Brett Cullum Cutsleeve Boys Comedy Larry Lingle D.E.B.S Comedy Joseph Fleurinor Dorian Blues Comedy Larry Lingle East Side Story Comedy Larry Lingle Eating Out Comedy Huy Truong Eating Out 2: Sloppy Seconds Comedy Huy Truong Eating Out: All you can eat Comedy Huy Truong Four-Faced Liar, The Comedy LGBT Resource Center Gay Bed and Breakfast of Terror (The) Comedy Beverly McPhail Get Your Stuff Comedy Larry Lingle Guys and Balls Comedy Larry Lingle Help! I'm a Boy Comedy LGBT Resource Center Is it Just Me? Comedy Brett Cullum It's My Party Comedy Brett Cullum Jeffrey Comedy Larry Lingle Kathy Griffin: Allegedly Comedy Chris Miller and Colleen Schmidt Kathy Griffin: She'll Cut A Bitch Comedy Huy Truong Kinky Boots Comedy Women's Resource Center Kiss Me Guido Comedy Brett Cullum Longhorns Comedy Brett Cullum Make the Yuletide Gay Comedy Brett Cullum Make the Yuletide Gay Comedy Brett Cullum Mambo Italiano Comedy Larry Lingle -

Closed-Captioned and Subtitled Titles

Libraries CLOSED-CAPTIONED AND SUBTITLED TITLES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 DVD-1717 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0254 DVD-4640 DVD-0812 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 10th Victim DVD-5591 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 11th Hour DVD-5026 2000 and Beyond: Confronting the Microbe Menace DVD-0126 12 DVD-1200 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-0260 12 and Holding DVD-5110 DVD-1239 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 12 Monkeys DVD-3375 2012 DVD-4759 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 2012 (Blu-Ray) DVD-7622 127 Hours DVD-8008 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 1408 DVD-7675 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 1776 DVD-0397 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 180 DVD-3999 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1900 DVD-4443 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 1900 House DVD-0500 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 1940s House DVD-3463 25th Hour DVD-2291 1964 DVD-7724 27 Dresses DVD-8204 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 28 Days Later DVD-4333 1968 Young Blood VHS-4607 DVD-6187 9/1/2015 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 8 1/2 DVD-3832 3 Penny Opera DVD-3329 8 Mile DVD-1639 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 9 Souls DVD-0372 3 Women DVD-4850 9 to 5 DVD-2063 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 9.99 DVD-5662 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs 30 Days Season 1 DVD-4981 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs 30 Days Season 2 DVD-4982 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-5) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs 30 Rock Season 1 DVD-7976 9th Company DVD-1383 300 DVD-6064 A.I. -

Feature Film Blu-Rays

Feature Film Blurays BLU ABO DISC 1 About time BLU ACR Across the universe BLU AGE DISC 1 The age of Adaline BLU ALL All is lost BLU AMA DISC 1 The amazing spiderman 2 BLU AME American history X BLU AME American sniper BLU AME DISC 1 American Ultra BLU AME DISC 13 American Crime Story: The People V. O. J. Simpson BLU AMY Amy BLU ANO DISC 1 Another year BLU ANO DISC 1 Another Earth BLU ANT AntMan BLU ANY DISC 1 Any given Sunday BLU APO Apollo 13 BLU AUG August BLU AVI The aviator BLU BAD DISC 1 Bad words BLU BAG DISC 1 Baggage claim BLU BAT Batman v Superman BLU BEI Being there BLU BEL Belle BLU BIG Big fish BLU BIG Big eyes BLU BIL DISC 1 Billy Elliot BLU BIR Birdman BLU BLA Black mass BLU BLA DISC 1 Black sea BLU BLO Blood diamond BLU BLU Blue Jasmine BLU BLU Blue velvet BLU BON Bonnie and Clyde BLU BOND SPE Spectre BLU BOND SPY The spy who loved me BLU BOO The book thief BLU BOY Boyhood BLU BOY The boy next door BLU BRE The breakup BLU BRE DISC 1 Breaking the waves BLU BRI Bridget Jones's diary BLU BRI DISC 1 Bridge of spies BLU BRO Brokeback Mountain BLU BRO Brooklyn BLU BUR Burnt BLU CAF DISC 1 Cafe Society BLU CAP Captain America. The winter soldier BLU CAP Capote BLU CAP DISC 1 Captain Phillips BLU CAS Cast away BLU CAT DISC 1 Catch my soul BLU CHI Chinatown BLU CHI DISC 1 Chicago BLU CIN DISC 1 Cinderella BLU CIN DISC 1 Cinderella BLU CLO DISC 1 Closed circuit BLU COB DISC 1 The cobbler BLU CON Concussion BLU CON The confirmation BLU CRA Crash BLU CRE Creed BLU CRI DISC 1 Crimson Peak BLU DAD DISC 1 Daddy's home BLU DAL DISC 1 Dallas buyers club BLU DAN The Danish Girl BLU DAN DISC 1 Danny Collins BLU DAR Dark places BLU DEA Masterpiece mystery. -

Celebrate the Best of British Film at the May Fair Hotel

Celebrate the Best of British Film at The May Fair Hotel As part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival The May Fair Hotel Gala will premiere ‘Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool’ London, UK – 2017: For the ninth consecutive year, The May Fair Hotel will be the Official Hotel of the 61st BFI London Film Festival in partnership with American Express®. To celebrate the best of British film, the five star hotel in the heart of Mayfair will be rolling out the red carpet and offering guests and visitors bespoke, cinematic experiences throughout the 12-day festival. During this year’s Festival, The May Fair’s annual Gala event on Wednesday 11th October will be the European premiere of Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. Starring Annette Bening (American Beauty, 20th Century Women) and Jamie Bell (Billy Elliot, Jane Eyre), directed by Paul McGuigan (Sherlock, Lucky Number Slevin) and produced by Barbara Broccoli (Spectre, Skyfall) and Colin Vaines (Gangs of New York, Coriolanus), Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool is a true story of the love affair between Gloria Grahame and young aspiring actor Peter Turner. Annette Bening and Jamie Bell vividly bring to the screen the intense romance between Hollywood icon Gloria Grahame and her much younger lover. In 1981, decades after she rose to fame in Hollywood, the Academy Award-winning star of The Big Heat, In a Lonely Place and The Bad and the Beautiful, Grahame (Bening) is treading the boards in a modest theatre production when she collapses in a Lancaster hotel.