Victoria & Abdul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr Saba Mahmood Bashir Assistant Professor Department of English

Dr Saba Mahmood Bashir Assistant Professor Department of English Jamia Millia Islamia New Delhi – 110025 [email protected] (primary) [email protected] (secondary) 9810046185 (Mobile) Specialisation/Research Interests Indian Writing in English Indian Literatures in English Translation Translation/Translation Studies Film/Urdu Poetry Courses Taught/ Teaching Indian Literature in Translation Literatures of India Dalit Literature Diploma in Translation Certificate in Translation Proficiency British Poetry Popular Literature and Culture Postcolonial Literature Review Writing Language and Communication Skills Indian Writings in English Filming Fiction Creative Writing Publications Books 1. Women of Prey, a translation of Saadat Hasan Manto’s Shikari Auratien, published by Speaking Tiger, October 2019. (ISBN No. 978-93-8923-132-8) Originally published in 1955 as Shikari Auratein, Women of Prey is a hugely entertaining and forgotten classic containing raunchy, hilarious short stories and profiles that show a completely different side of Manto. 2. Gulzar’s Aandhi: Insights into the Film, an analytical book on the film by the same name, published by HarperCollins India, February 2019. (ISBN No. 978-93-5302-508-3) At one level, Gulzar's Aandhi (1975) is a story of estranged love between two headstrong and individualistic personalities; at another, it is a tongue-in-cheek comment on the political scenario of the country. Through a close textual analysis of the film, this book examines in detail its stellar cast, the language and dialogues, and the evergreen songs which had a major role in making the film a commercial success. 3. Tehreer Munshi Premchand Ki Godaan Nirmala and other stories, screenplays by Gulzar, a work of translation from Hindustani into English, published by Roli Books, May 2016. -

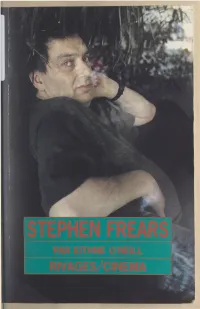

Stephen Frears Par Eithne O'neill

STEPHEN FREARS PAR EITHNE O'NEILL Collection dirigée par Francis Bordat RIVAGES Du même auteur: Lubitsch ou la satire romanesque, en collaboration avec Jean-Loup Bourget, Stock, 1987; rééd. Flammarion, coll. «Champs Contre-Champs », 1990. Crédits photographiques : British Film Institute (pages 15, 17, 26, 28, 29, 35, 37, 39, 41, 43, 77, 79, 81, 84, 87, 90, 92, 103 haut, 105, 109, 135), archives Cahiers du cinéma (couverture, pages 47, 50, 101, 129), collection Michel Ciment (pages 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21, 23, 25, 31, 44, 45, 52, 55, 57, 58, 59, 60, 62, 64, 65, 66, 67, 69, 70, 71, 72, 97, 99, 102, 103 bas, 104, 106, 107, 108 bas, 111, 116, 126, 128, 131, 134, 136, 137, 164, 166, 167, 178, 182, 184, 187, 190, 191, 199, 204, 208, 209, 211), ITC Entertainment (pages 82, 83), Neville Smith (pages 108 haut, 143). © Éditions Payot & Rivages, 1994 106, bd Saint-Germain 75006 PARIS ISBN: 2 - 86930 - 844 - 2 ISSN: 0298 - 0088 A Joëlle Pour leur aide et leur collaboration, je tiens à remercier les personnes suivantes: Neville Smith, romancier, scénariste, acteur et musicien ; Hanif Kureishi, qui m'a autorisée à reproduire son «Intro- duction à My Beautiful Laundrette » ; Christian Bourgois, qui m'a autorisée à reproduire le texte de Hanif Kureishi dans sa traduction française; Patrick O'Byrne, sans qui ce livre n'aurait pas pu être écrit; Reinbert Tabbert; Michael Dwyer, critique de cinéma, The Irish Times ; Michel Ciment ; Hubert Niogret ; Jon Keeble (ITC), qui a organisé pour moi une projection de Bloody Kids ; Maria Stuff, independent film resear- cher, Londres ; Kathleen Norrie ; Maeve Murphy ; Kate Lenehan; Jacques Bover; et Neville Smith, qui a bien voulu me prêter les photos prises par lui. -

Multiculturalism and Creative British South Asian Films Denise Tsang1,A

2017 3rd Annual International Conference on Modern Education and Social Science (MESS 2017) ISBN: 978-1-60595-450-9 Multiculturalism and Creative British South Asian Films Denise Tsang1,a,* and Dahlia Zawawi2,b 1Henley Business School, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, UK 2Department of Management and Marketing, Universiti Putra Malaysia,Serdang, Malaysia [email protected], [email protected] *Corresponding author Keywords: Multiculturalism, Creativity, Competitiveness, British South Asian Films Abstract. Globalization has enabled countries such as the UK to attain multiculturalism; however, there is no investigation in relation to the advantages of multiculturalism at the film industry level. Multiculturalism is related to the Commonwealth immigration after the Second World War period. The introduction of new cultures into the UK has enabled the growth and development of successful global industries such as the British Urban Music and British Asian Film, which have prospered over time and have now become mainstream export-led industries. Why is cultural diversity significant towards the generation of competitive advantages within the British South Asian film sector? We will explore the country specific advantage of multiculturalism in the UK and their impact on creativity of screenwriters that has contributed to successful films in the industry. Introduction Multiculturalism has been defined by Libretti as a ‘careful attention to and respect for a diversity of cultural perspectives’ [1]. Berry explained the concept in terms of the maintenance of cultural heritage and the relationships sought among cultural groups as shown in the following figure [2]. Figure 1 shows that if a society enables individuals from cultural minority groups to maintain their cultural uniqueness while establishing relationships with the core cultural groups, multiculturalism is achieved. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in the Young Victoria (2009)

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in The Young Victoria (2009) Julia Kinzler (Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany) Abstract This article explores the ambivalent re-imagination of Queen Victoria in Jean-Marc Vallée’s The Young Victoria (2009). Due to the almost obsessive current interest in Victorian sexuality and gender roles that still seem to frame contemporary debates, this article interrogates the ambiguous depiction of gender relations in this most recent portrayal of Victoria, especially as constructed through the visual imagery of actual artworks incorporated into the film. In its self-conscious (mis)representation of Victorian (royal) history, this essay argues, The Young Victoria addresses the problems and implications of discussing the film as a royal biopic within the generic conventions of heritage cinema. Keywords: biopic, film, gender, genre, iconography, neo-Victorianism, Queen Victoria, royalty, Jean-Marc Vallée. ***** In her influential monograph Victoriana, Cora Kaplan describes the huge popularity of neo-Victorian texts and the “fascination with things Victorian” as a “British postwar vogue which shows no signs of exhaustion” (Kaplan 2007: 2). Yet, from this “rich afterlife of Victorianism” cinematic representations of the eponymous monarch are strangely absent (Johnston and Waters 2008: 8). The recovery of Queen Victoria on film in John Madden’s visualisation of the delicate John-Brown-episode in the Queen’s later life in Mrs Brown (1997) coincided with the academic revival of interest in the monarch reflected by Margaret Homans and Adrienne Munich in Remaking Queen Victoria (1997). Academia and the film industry brought the Queen back to “the centre of Victorian cultures around the globe”, where Homans and Munich believe “she always was” (Homans and Munich 1997: 1). -

Crimeindelhi.Pdf

CRIME IN DELHI 2018 as against 2,23,077 in 2017. The yardstick of crime per lakh of population is generally used worldwide to compare The social churning is quite evident in the crime scene of the crime rate. Total IPC crime per lakh of population was 1289 capital. The Delhi Police has been closely monitoring the ever- crimes during the year 2018, in comparison to 1244 such changing modus operandi being adopted by criminals and crimes during last year. adapting itself to meet these new challenges head-on. The year 2018 saw a heavy thrust on modernization coupled with unrelenting efforts to curb crime. Here too, there was a heavy TOTAL IPC CRIME mix of the state-of-the-art technology with basic policing. The (per lakh of population) police maintained a delicate balance between the two and this 1500 was evident in the major heinous cases worked out this year. 1243.90 1289.36 Along with modern investigative techniques, traditional beat- 1200 1137.21 level inputs played a major role in tackling crime and also in 900 its prevention and detection. 600 Some of the important factors impacting crime in Delhi are 300 the size and heterogeneous nature of its population; disparities in income; unemployment/ under employment, consumerism/ 0 materialism and socio-economic imbalances; unplanned 2016 2017 2018 urbanization with a substantial population living in jhuggi- jhopri/kachchi colonies and a nagging lack of civic amenities therein; proximity in location of colonies of the affluent and the under-privileged; impact of the mass media and the umpteen TOTAL IPC advertisements which sell a life-style that many want but cannot afford; a fast-paced life that breeds a general proclivity 250000 223077 236476 towards impatience; intolerance and high-handedness; urban 199107 anonymity and slack family control; easy accessibility/means 200000 of escape to criminal elements from across the borders/extended 150000 hinterland in the NCR region etc. -

Cheri-Dossier-De-Presse-Francais.Pdf

Bill Kenwright présente Michelle Pfeiffer Rupert Friend Kathy Bates Durée : 1h30 - Format : Scope - Son : SRD SORTIE LE 8 AVRIL 2009 DISTRIBUTION PRESSE Pathé Distribution Jérôme Jouneaux, Isabelle Duvoisin & Matthieu Rey 2 rue Lamennais 10, rue d’Aumale 75008 Paris 75009 Paris Tél. : 01 71 72 30 00 Tél. : 01 53 20 01 20 Dossier de presse et photos téléchargeables sur : www.pathedistribution.com SYNOPSIS Dans le Paris du début du XXème siècle, Léa de Lonval finit une carrière heureuse de courtisane aisée en s’autorisant une liaison avec le fils d’une ancienne consoeur et rivale, le jeune Fred Peloux, surnommé Chéri. Six ans passent au cours desquels Chéri a beaucoup appris de la belle Léa, aussi Madame Peloux décrète-t-elle qu’il est grand temps de songer à l’avenir de son fils et au sien propre... Il faut absolument marier Chéri à la jeune Edmée, fille unique de la riche Marie-Laure. Alors que le moment fatidique approche, Léa et Chéri tentent de se résoudre à cette séparation imminente tout en s’apercevant qu’ils sont beaucoup plus attachés l’un à l’autre qu’ils ne voulaient bien l’admettre. LES COURTISANES Surnommées les “grandes horizontales”, les courtisanes étaient de biens. Elles ne pouvaient monnayer que leur personnalité très en vogue dans le Paris de la fin du XIXe siècle. et leur beauté et les plus perspicaces d’entre elles savaient que leur prestige ne survivrait pas à leurs charmes. Célèbres à travers le monde pour leur beauté, leur esprit, leur conversation et leur savoir-faire, ces demi-mondaines étaient Parmi les courtisanes les plus en vue de l’époque, il y eut au centre de la vie sociale et politique de Paris, divertissant les Apollonie Sabatier, qui accueillit dans son salon des hommes les plus puissants des arts, de la noblesse et de l’État intellectuels tels que Baudelaire et Flaubert, Marie Duplessis tout en restant isolées de la société dans leur monde clos. -

Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442

English 252: Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442-07-387-1551 61/63 Cartwright Gardens London, UK WC1H 9EL [*Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 28 *1:00 p.m. Beauties and Beasts. Retold by Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate). Adapted by Tim Supple. Dir Melly Still. Design by Melly Still and Anna Fleischle. Lighting by Chris Davey. Composer and Music Director, Chris Davey. Sound design by Matt McKenzie. Cast: Justin Avoth, Michelle Bonnard, Jake Harders, Rhiannon Harper- Rafferty, Jack Tarlton, Jason Thorpe, Kelly Williams. Hampstead Theatre *7.30 p.m. Little Women: The Musical (2005). Dir. Nicola Samer. Musical Director Sarah Latto. Produced by Samuel Julyan. Book by Peter Layton. Music and Lyrics by Lionel Siegal. Design: Natalie Moggridge. Lighting: Mark Summers. Choreography Abigail Rosser. Music Arranger: Steve Edis. Dialect Coach: Maeve Diamond. Costume supervisor: Tori Jennings. Based on the book by Louisa May Alcott (1868). Cast: Charlotte Newton John (Jo March), Nicola Delaney (Marmee, Mrs. March), Claire Chambers (Meg), Laura Hope London (Beth), Caroline Rodgers (Amy), Anton Tweedale (Laurie [Teddy] Laurence), Liam Redican (Professor Bhaer), Glenn Lloyd (Seamus & Publisher’s Assistant), Jane Quinn (Miss Crocker), Myra Sands (Aunt March), Tom Feary-Campbell (John Brooke & Publisher). The Lost Theatre (Wandsworth, South London) Thursday December 29 *3:00 p.m. Ariel Dorfman. Death and the Maiden (1990). Dir. Peter McKintosh. Produced by Creative Management & Lyndi Adler. Cast: Thandie Newton (Paulina Salas), Tom Goodman-Hill (her husband Geraldo), Anthony Calf (the doctor who tortured her). [Dorfman is a Chilean playwright who writes about torture under General Pinochet and its aftermath. -

Victoria, Koningin

Victoria, koningin Julia Baird ictoria Vkoningin Een intieme biografie van de vrouw die een wereldrijk regeerde Nieuw Amsterdam Vertaling Chiel van Soelen en Pieter van der Veen Oorspronkelijke titel Victoria the Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire. Penguin Random House LLC, New York © 2016 Julia Baird Kaarten en stamboom © 2016 David Lindroth, Inc. © 2017 Nederlandse vertaling: Chiel van Soelen en Pieter van der Veen/ Nieuw Amsterdam Voor de herkomst van het beeldmateriaal, zie de illustratieverantwoording vanaf blz. 753 Alle rechten voorbehouden Tekstredactie Marianne Tieleman Register Ansfried Scheifes Omslagontwerp Bureau Beck Omslagbeeld: Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Victoria (1842, detail)/Bridgeman Images. Auteursportret Alex Ellinghausen nur 681 isbn 978 90 468 2179 4 www.nieuwamsterdam.nl Voor Poppy en Sam, mijn betoverende kinderen [Koningin Victoria] behoorde tot geen enkele denkbare categorie van vorsten of vrouwen, zij vertoonde geen gelijkenis met een aristocratische Engelse dame, niet met een rijke Engelse middenklassevrouw, noch met een typische prinses van een Duits hof (...). Ze regeerde langer dan de andere drie koninginnen samen. Tijdens haar leven kon ze nooit worden verward met iemand anders, en dat zal ook in de geschiedenis zo zijn. Uit- drukkingen als ‘mensen zoals koningin Victoria’ of ‘dat soort vrouw’ konden voor haar niet worden gebruikt (...). Meer dan zestig jaar lang was ze gewoon ‘de konin- gin’, zonder voor- of achtervoegsel.1 Arthur PONSONBY We kijken allemaal of we al tekenen van -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860- 1901 Charles Vincent Reed, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Richard Price Department of History ABSTRACT: The dissertation explores the development of global identities in the nineteenth-century British Empire through one particular device of colonial rule – the royal tour. Colonial officials and administrators sought to encourage loyalty and obedience on part of Queen Victoria’s subjects around the world through imperial spectacle and personal interaction with the queen’s children and grandchildren. The royal tour, I argue, created cultural spaces that both settlers of European descent and colonial people of color used to claim the rights and responsibilities of imperial citizenship. The dissertation, then, examines how the royal tours were imagined and used by different historical actors in Britain, southern Africa, New Zealand, and South Asia. My work builds on a growing historical literature about “imperial networks” and the cultures of empire. In particular, it aims to understand the British world as a complex field of cultural encounters, exchanges, and borrowings rather than a collection of unitary paths between Great Britain and its colonies. ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860-1901 by Charles Vincent Reed Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Advisory Committee: Professor Richard Price, Chair Professor Paul Landau Professor Dane Kennedy Professor Julie Greene Professor Ralph Bauer © Copyright by Charles Vincent Reed 2010 DEDICATION To Jude ii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS Writing a dissertation is both a profoundly collective project and an intensely individual one. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

PIERS HAMPTON Visual Effects Producer/Supervisor

PIERS HAMPTON Visual Effects Producer/Supervisor FILMS DIRECTOR STUDIO/PRODUCTION “THE PARTY” SALLY POTTER ADVENTURE PICTURES On-Set Supervisor Alice Dawson, Karl Liegis “HOW TO TALK TO GIRLS AT JOHN CAMERON MITCHELL SEE-SAW FILMS PARTIES” HANWAY FILMS On-Set Supervisor “THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY” MATT BROWN EDWARD R. PRESSMAN FILM VFX Supervisor/VFX Producer Matt Brown, Ed Pressman “BITTER HARVEST” GEORGE MENDELUK DEVIL’S HARVEST PRODUCTION Additional VFX Super / Chad Baranger, Jaye Gazeley VFX Unit Director (Re-shoots) “DAWN” ROMED WYDER DSCHOINT VENTSCHR FILMPRODUKTION VFX Supervisor/Producer Samir, Romed Wyder “BHOPAL” RAVI KUMAR RISING STAR VFX Supervisor/Producer Ravi Walia Prime Focus – Sole Vendor “VAMPIRE ACADEMY” MARK WATERS THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY Sr. VFX Producer Deepak Nayar Prime Focus - Sole Vendor “LEGENDARY” ERIC STYLES CHINA FILM GROUP VFX Producer Matthew Kuipers, Xiaodong Liu “THE CRISTMAS CANDLE” JOHN STEPHENSON PINEWOOD FILMS VFX Supervisor Tom Newman Prime Focus – Sole Vendor “THE WEE MAN” RAY BURDIS CARNABY INTERNATIONAL VFX Producer Mike Loveday Prime Focus - Sole Vendor “STORAGE 24” JOHANNES ROBERTS UNIVERSAL PICTURES Sr. VFX Producer Noel Clark Prime Focus - Sole Vendor “OUTPOST 2: BLACK SUN” STEVE BARKER MATADOR Exec Supervisor – Prime Focus Nigel Thomas “THE NUTCRACKER IN 3D” ANDREY KONCHALOVSKIY VNESHECONOMBANK VFX Producer / Creature Effects Andrey Konchalovskiy, Paul Lowin Producer / Adtl VFX Supervisor “TAMARA DREWE” STEPHEN FREARS RUBY FILMS VFX Producer / Set Supervision Alison Owen, Tracey Seaward Bluff Hampton – Sole Vendor “SCOTT PILGRIM VS. THE WORLD” EDGAR WRIGHT UNIVERSAL PICTURES VFX Producer – Bluff Hampton Eric Gitter, Nira Park “THE ARBOR” CLIO BARNARD ARTANGEL MEDIA VFX Producer Tracy O’Riordan Bluff Hampton – Sole Vendor “NINE” ROB MARSHALL THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY VFX Producer John DeLuca, Rob Marshall Bluff Hampton – Sole Vendor Piers Hampton -Continued- “THE DEATHS OF IAN STONE” DARIO PIANA LIONSGATE VFX Producer – Bluff Hampton Brian J.