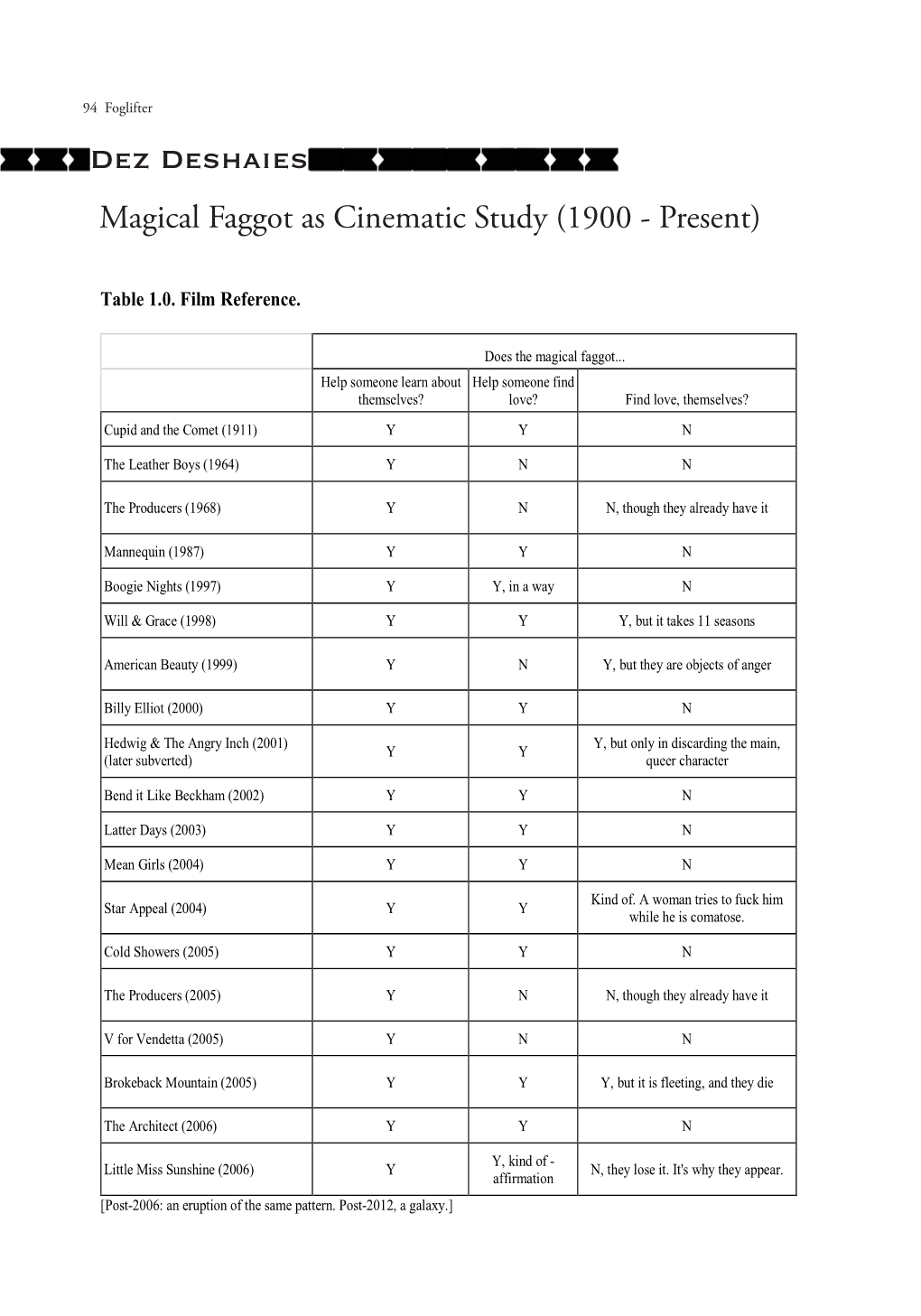

Magical Faggot As Cinematic Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1St February 2020 Resource Pack

Brought to you by 31st January - 1st february 2020 resource pack Kindly supported by: The Shoresh Charitable Trust Brought to you by TRANSFORMING THE LANDSCAPE OF MENTAL HEALTH A panel discussion Tuesday 28 January, 7.30PM, JW3 London Join Jami, The Mental Health Service for our Community, together with JW3 for a panel discussion to mark The Mental Health Awareness Shabbat. The panel will focus on how collaboration between organisations in our community can help improve our mental health and how we can best work together to achieve this, before opening up the discussion to a Q&A from the audience to our panel of experts: • Laurie Rackind, Chief Executive of Jami • Dr Ellie Cannon, NHS GP, author and Mail on Sunday doctor • Rabbi Miriam Berger, Finchley Reform Synagogue • Laurence Field, Director of Gateways at JW3 • Panel to be chaired by Adam Dawson, Barrister and Chair of Jami’s Board of Trustees To out more, or to book tickets please Brought to you by visit jamiuk.org/mhas Registered Charity 1003345. A Company Limited by Guarantee 2618170. 1 Brought to you by contents 2 Welcome by Laurie Rackind, Jami Chief Executive 3 About Jami 4 Why mark the Mental Health Awareness Shabbat? 5 LETTER FROM A JAMI SERVICE USER 8 Key Facts on Mental Health 9 NHS 5 Ways to Wellbeing 10 What can you do? 11 suggested programmes 13 Fundraising for MHFA Training 14 Suggestions for individuals 15 Guidelines for sharing lived experience 16 Youth materials & IDEAS 47 young professionals 50 sermons 60 Yoga, Pilates, Mindfulness and Mental Health 62 Useful Resources List 2 Brought to you by Welcome Dear Friends, Thank you for supporting The Mental Health Awareness Shabbat and for helping to raise awareness and promote conversations around mental health and mental illness in the Jewish Community. -

Family in Films

Travail de maturité – ANGLAIS Sujet no 13 Family in Films “All happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Anna Karenina, Leon Tolstoy. Whether dysfunctional, separated by exile, torn apart by history, laden with secrecy, crazy, loving, caring, smothering - and even perhaps happy, family is an endless source of investigation about human relations and social groups. In this research paper, you will be able to question Leon Tolstoy’s statement and explore how films envision new and older forms of families. Some examples of films relevant to this research paper: Festen (Thomas Vintenterberg, 1998) Parasite (Bong Joon-ho, 2019) L’Heure d’été (Olivier Assayas, 2008) Family Romance, LLC (Werner Herzog, 2019) Un conte de Noël (Arnaud Desplechin, Crooklyn (Spike Lee, 1994) 2008) Sorry, We Missed You (Ken Loach, 2019) La Fête de famille (Cédric Kahn, 2019) I, Daniel Blake ( Ken Loach, 2016) After the Storm (海よりもまだ深く, Umi yori Jungle Fever (Spike Lee, 1991) mo mada fukaku, Hirokazu Rodinný Film (Family Film, Olmo Omerzu, Kore-eda, 2016) 2015) Nobody Knows (誰も知らない, Dare mo So Long My Son (地久天长, Di jiu tian chang shiranai, Hirokazu Kore-eda, Wang Xiaoshuai, 2019) 2004) Still Life (三峡好人, Sānxiá hǎorén, Jia Like Father, Like Son (そして父になる, Zhangke, 2006) Soshite chichi ni naru, Hirokazu Amreeka (Cherien Dabis, 2009) Kore-eda, 2013) Tokyo Sonata (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2008) Our Little Sister (海街diary, Umimachi American Beauty (Sam Mendes, 1999) Diary, Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2015) The Royal Tenenbaums (Wes Anderson, Still Walking -

Scorpions Wolf Parade Lady Gaga

Music.Gear.Style. No.31 August 2010 Scorpions Sonus Faber Wolf Parade Sneak Peek The Lady GaGa Beer Snob Returns A Private Session with A&E’s Lynn Hoffman Mellencam Toronto’s Costello Hockey Museum Maiden B&W 805D BestCoast Si m 75 0 More Gear! Wavves More Music! Stereotypes Sound City Audio Classics Shelley’s Stereo Audio Vision S F Daytona Beach, FL 32114 Denville, NJ 07834 Vestal, NY 13850 Hi Fi Center San Francisco, CA 94109 386-253-7093 973-627-0083 607-766-3501 Woodland Hills, CA 91367 415-641-1118 818-716-8500 Sound Components The Sound Concept Home Theater Concepts Audio FX Coral Gables, FL 33146 Bedford Hills, NY 10507 Morton, IL 61550 DSS- Dynamic Sacramento, CA 95825 305-665-4299 914-244-0900 309-266-6640 Sound Systems 916-929-2100 Carlsbad, CA 92088 Audio Advisors Sound Image Audio and Global Sight & Sound 760-723-2535 Media Enviroments West Palm Beach, FL 33409 Video Design Group Sussex, WI 53089 San Rafael, CA 94901 561-478-3100 Carrollton, TX 75006 262-820-0600 L & M Home Entertainment 415-456-1681 972-503-4434 Tempe, AZ 85285 Independence Audio Freeman’s Stereo 480-403-0011 Pro Home Systems Independence, MO 64055 Advanced Home Charlotte, NC 28216 Oakland, CA 94609 816-252-9782 Theater Systems 704-398-1822 Joseph Cali Systems Design 510-653-4300 3800 Watts. Plano, TX 75075 Santa Monica, CA 90404 Definitive Audio 972-516-1849 Hi Fi Buys 310-453-3297 Overture Bellevue, WA 98005 Nashville, TN 37211 Winnington, DE 19803 360 lbs. -

Quiet and Melancholy. This MUSIC Plays Over All of the Opening Scenes

We begin with MUSIC -- quiet and melancholy. This MUSIC plays over all of the opening scenes: EXTREME CLOSE UP The silent, slo-mo image of a Miss America being crowned. She cries and hugs the runners-up as she has the tiara pinned on her head. Then -- carrying her bouquet -- she strolls down the runway, waving and blowing kisses. INT. REC ROOM - DAY A six year old girl sits watching the show intently. This is OLIVE. She is big for her age and slightly plump. She has frizzy brown hair and wears black-rimmed glasses. She studies the show very earnestly. Then, using a remote, she FREEZES the image. Absently, she holds up one hand and mimics the waving style of the Miss America. She REWINDS the tape, and starts all over again. Again, Miss America hears her name announced, and once again breaks down in tears -- overwhelmed and triumphant. RICHARD (V.O.) There’s two kinds of people in this world: Winners...and Losers. INT. CLASSROOM - DAY RICHARD (45) stands in front of a white-board in a community college classroom. He wears khaki shorts, a golf shirt, sneakers. His peppy, upbeat demeanor just barely masks a seething sense of insecurity and frustration. There are eleven students in a room that could easily fit fifty. RICHARD If there’s one thing you take away from the nine weeks we’ve spent here together, it should be this: Winners and Losers. What’s the difference? 2. Richard turns with a pointer and enumerates his points, which are listed on the white board. -

Oscars and America 2011

AMERICA AND THE MOVIES WHAT THE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINEES FOR BEST PICTURE TELL US ABOUT OURSELVES I am glad to be here, and honored. I spent some time with Ben this summer in the exotic venues of Oxford and Cambridge, but it was on the bus ride between the two where we got to share our visions and see the similarities between the two. I am excited about what is happening here at Arizona State and look forward to seeing what comes of your efforts. I’m sure you realize the opportunity you have. And it is an opportunity to study, as Karl Barth once put it, the two Bibles. One, and in many ways the most important one is the Holy Scripture, which tells us clearly of the great story of Creation, Fall, Redemption and Consummation, the story by which all stories are measured for their truth, goodness and beauty. But the second, the book of Nature, rounds out that story, and is important, too, in its own way. Nature in its broadest sense includes everything human and finite. Among so much else, it gives us the record of humanity’s attempts to understand the reality in which God has placed us, whether that humanity understands the biblical story or not. And that is why we study the great novels, short stories and films of humankind: to see how humanity understands itself and to compare that understanding to the reality we find proclaimed in the Bible. Without those stories, we would have to go through the experiences of fallen humanity to be able to sympathize with them, and we don’t want to have to do that, unless we have a screw loose somewhere in our brain. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Lewisville ISD 2017 Support Staff Summer Conference

Lewisville ISD 2017 Support Staff Summer Conference Friday, July 14 #lisdlearns 7:45 a.m. – 8:00 a.m. Registration & Packet Pick-Up 8:00 a.m. – 8:10 a.m. Welcome 8:20 a.m. – 9:35 a.m. Session 1 9:45 a.m. – 11:00 a.m. Long Session 1 & 2 Session 2 11:00 a.m. – 11:35 a.m. Lunch & Door Prizes! 11:45 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. Session 3 1:10 p.m. – 2:25 p.m. Long Session 3 & 4 Session 4 2:25 p.m. – 2:30 p.m. Turn in Survey for Credit NOTES: * You must attend all day to receive credit. * If a session is full, you will need to find another session to attend. * You will receive a sticker for each session you attend. Place each sticker on your survey. * At the end of each session, fill out what you learned and that you will use moving forward on your notes sheet. * Turn in your finished survey to your last presenter before leaving the conference. Long Sessions: 2 hours 30 min Title Movie Inspired Title Handout Room # Battling Behavioral Issues The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Page 8 Library Google Drive & Docs DRIVING miss Google Page 6 E212- Cart G207- Cart Google Forms Lights, Camera, Action with Google Forms Page 7 E209- Cart Munis - Morning Only Show me the MONEY Page 7 E238-LAB NEW! Multi - Generations in the Back to the Future Page 6 F205 Workplace - Afternoon only NEW! True Colors Inside Out Page 4 F211 Short Sessions: 1 hour 15 min Title Movie Inspired Title Handout Room # NEW! Strategies for Student Success Subt itles are my Language Lifeline Page 5 E203 NEW! Hook kids into learning Pirates of the Classroom Page 5 E214 NEW! Keeping -

1 STANFORD FALL 2012 COURSE INFO/SYLLABUS: Thatʼs A

STANFORD FALL 2012 COURSE INFO/SYLLABUS: Thatʼs a Great Idea for a Movie: The Making of a Strong Screenplay Required Texts: 1. Robert McKee Story: Substance, Structure, Principles 2. Lajos Egri The Art of Dramatic Writing 3.Linda Seger Making a Good Script Great 4. Michael Arndt Little Miss Sunshine Shooting Script 5. David Small Imogeneʼs Antlers 6. Annie Proux, Larry McMurty, Diana Ossana Brokeback Mountain: Story to Screenplay 7.Screenwriting software. Final Draft is considered the standard in screenwriting software, but retails for $150 or more. Celtx is an open-source program that is free and recommended. It can be found online at versiontracker.com. Note: Other materials will include a combination of online resources and uploaded reading, such as scripts. The films assigned for viewing are available on demand at either Amazon.com or Netflix. Note on the required texts: I will select excerpts from each text. You will not be required to read the above texts in anything close to their entirety (with the exception of the scripts and short stories). They are, however, a good foundation for your screenwriting instruction library and will be useful to you as you continue your journey beyond our ten weeks. Supplemental Reading: Each week, Iʼll provide additional reading or viewing related to the topic at hand. These selections are totally optional, and only in case youʼve finished the assignments and have the time or desire to explore further. 1 Syllabus In Brief: Week One: Screenplays & Ice Breakers: Introductions (10/01-10/07) Lajos Egri on Premise: The Art of Dramatic Writing pgs. -

![Billy Elliot the Musical: Visual Representations of Working-Class Masculinity and the All-Singing, All-Dancing Bo[D]Y](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2054/billy-elliot-the-musical-visual-representations-of-working-class-masculinity-and-the-all-singing-all-dancing-bo-d-y-1312054.webp)

Billy Elliot the Musical: Visual Representations of Working-Class Masculinity and the All-Singing, All-Dancing Bo[D]Y

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a paper published in Studies in Musical Theatre. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10354/ Published paper Rodosthenous, George (2007) Billy Elliot The Musical: visual representations of working-class masculinity and the all-singing, all-dancing bo[d]y. Studies in Musical Theatre , 1 (3). pp. 275-292. White Rose Research Online [email protected] ARTICLE NAME Billy Elliot The Musical: Visual representations of working-class masculinity and the all-singing, all-dancing bo[d]y. AUTHOR NAME GEORGE RODOSTHENOUS ABSTRACT According to Cynthia Weber, „[d]ance is commonly thought of as liberating, transformative, empowering, transgressive, and even as dangerous‟. Yet, ballet as a masculine activity, it still remains a suspect phenomenon. This paper will challenge this claim in relation to Billy Elliot the Musical and its critical reception. The transformation of the visual representation of the human body on stage (from an ephemeral existence to a timeless work of art) will be discussed and analysed vis-a-vis the text and sub-texts of Stephen Daldry's direction and Peter Darling‟s choreography. The dynamics of working-class masculinity will be contextualised within the framework of the family, the older female, the community, the self and the act of dancing itself. KEYWORDS Billy Elliot, masculinity, male dancers, dancing musicals, representations of the male AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY George Rodosthenous is Lecturer in Music Theatre at the School of Performance and Cultural Industries of the University of Leeds. -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

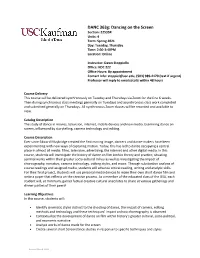

DANC 363G Syllabus S21

DANC 363g: Dancing on the Screen Section: 22535R Units: 4 Term: Spring 2021 Day: Tuesday, Thursday Time: 2:00-3:40PM Location: Online Instructor: Dawn Stoppiello Office: KDC 222 Office Hours: By appointment Contact Info: [email protected], (503) 989-4170 (text if urgent) Professor will reply to emails/calls within 48 hours Course Delivery This course will be delivered synchronously on Tuesday and Thursdays via Zoom for the first 6 weeks. Then during synchronous class meetings generally on Tuesdays and asynchronous class work completed and submitted generally on Thursdays. All synchronous Zoom classes will be recorded and available to view. Catalog Description The study of dance in movies, television, internet, mobile devices and new media. Examining dance on screen, influenced by storytelling, camera technology and editing. Course Description Ever since Edward Muybridge created the first moving image, dancers and dance-makers have been experimenting with new ways of capturing motion. Today, this has led to dance occupying a central place in almost all media: films, television, advertising, the internet and other digital media. In this course, students will investigate the history of dance on film both in theory and practice, situating seminal works within their greater socio-cultural milieu as well as investigating the impact of choreography, narrative, camera technology, editing styles, and music. Through substantive analysis of course readings and assigned media, students will advance critical reading, writing and analytic skills. For their final project, students will use personal media devices to make their own short dance film and write a paper that reflects on the creative process. -

Group Forms to Study High Tech for School Lating a Technology Plan

CASS CITY n‘QONICLE VOLUME 86,NUMBER 9 CASS CITY, MICHIGAN .- . - WED 4TY CENTS 12 PAGES PLUS ONE SUPPLEMENT I Group forms to study high tech for school lating a technology plan. by Brian D. Bell A WIDE VARIETY An entire set of encyclope- Staff Writer The committee and its pur- dias with text, photos and Psehave the Support of the A *OUp Of more than 2o &e thing be committe synthesized music could be Tuscola County area resi- cm City School Board. determine is what Stored On a Single disc, and dents are gearing up to take a the district’s computer accessing the information critical look at the state of UPGRADES NEEDED n@sae,and whetherthose would requireonly a few key technology in Cass City needs Ne being met, accord- strokes, he continued- The schools and how to improve Committee Chahlan ing to ~~hfiTownsend, encyclopedia could be Up- it. George Bushon& computer committee member and di- dated for about $100 allnu- Membersof theCassCity teacher at the City rector of Regional Educa- Educational Technology middle and high schools, tiond Media Center In addition, networking Planning Committee met for provided the PUP with in- Many schools in the United allows different computers thefirst&neThws&yinthe sight into the poor state Of states have first- and set- t0 COmmUniCak With each A MARLETTE WOMAN was injured Monday morning when her car struck a Cass City figh School li- the schOO1s’computer Pro- ond-grade students working Other Via telephone no mat- brary. gram. with computers on a daily ter where they ate in the parked pickup truck near the intersection of M-53 and Shabbona Road.