Nagty-Occasional-Paper-17-Doing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

![Billy Elliot the Musical: Visual Representations of Working-Class Masculinity and the All-Singing, All-Dancing Bo[D]Y](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2054/billy-elliot-the-musical-visual-representations-of-working-class-masculinity-and-the-all-singing-all-dancing-bo-d-y-1312054.webp)

Billy Elliot the Musical: Visual Representations of Working-Class Masculinity and the All-Singing, All-Dancing Bo[D]Y

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ This is an author produced version of a paper published in Studies in Musical Theatre. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10354/ Published paper Rodosthenous, George (2007) Billy Elliot The Musical: visual representations of working-class masculinity and the all-singing, all-dancing bo[d]y. Studies in Musical Theatre , 1 (3). pp. 275-292. White Rose Research Online [email protected] ARTICLE NAME Billy Elliot The Musical: Visual representations of working-class masculinity and the all-singing, all-dancing bo[d]y. AUTHOR NAME GEORGE RODOSTHENOUS ABSTRACT According to Cynthia Weber, „[d]ance is commonly thought of as liberating, transformative, empowering, transgressive, and even as dangerous‟. Yet, ballet as a masculine activity, it still remains a suspect phenomenon. This paper will challenge this claim in relation to Billy Elliot the Musical and its critical reception. The transformation of the visual representation of the human body on stage (from an ephemeral existence to a timeless work of art) will be discussed and analysed vis-a-vis the text and sub-texts of Stephen Daldry's direction and Peter Darling‟s choreography. The dynamics of working-class masculinity will be contextualised within the framework of the family, the older female, the community, the self and the act of dancing itself. KEYWORDS Billy Elliot, masculinity, male dancers, dancing musicals, representations of the male AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY George Rodosthenous is Lecturer in Music Theatre at the School of Performance and Cultural Industries of the University of Leeds. -

DANC 363G Syllabus S21

DANC 363g: Dancing on the Screen Section: 22535R Units: 4 Term: Spring 2021 Day: Tuesday, Thursday Time: 2:00-3:40PM Location: Online Instructor: Dawn Stoppiello Office: KDC 222 Office Hours: By appointment Contact Info: [email protected], (503) 989-4170 (text if urgent) Professor will reply to emails/calls within 48 hours Course Delivery This course will be delivered synchronously on Tuesday and Thursdays via Zoom for the first 6 weeks. Then during synchronous class meetings generally on Tuesdays and asynchronous class work completed and submitted generally on Thursdays. All synchronous Zoom classes will be recorded and available to view. Catalog Description The study of dance in movies, television, internet, mobile devices and new media. Examining dance on screen, influenced by storytelling, camera technology and editing. Course Description Ever since Edward Muybridge created the first moving image, dancers and dance-makers have been experimenting with new ways of capturing motion. Today, this has led to dance occupying a central place in almost all media: films, television, advertising, the internet and other digital media. In this course, students will investigate the history of dance on film both in theory and practice, situating seminal works within their greater socio-cultural milieu as well as investigating the impact of choreography, narrative, camera technology, editing styles, and music. Through substantive analysis of course readings and assigned media, students will advance critical reading, writing and analytic skills. For their final project, students will use personal media devices to make their own short dance film and write a paper that reflects on the creative process. -

Printable Version

GOODSPEED MUSICALS AUDIENCE INSIGHTS TABLE OF CONTENTS SEPT 13 - NOV 24, 2019 THE GOODSPEED Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writers.....................................................................................................................................................................................6 Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................8 Director's Vision......................................................................................................................................................................................9 The 1984 British Miners Strike........................................................................................................................................................10 A Billy Elliot Glossary...........................................................................................................................................................................12 The Royal Ballet School.....................................................................................................................................................................14 -

Billy Elliot

LEVEL 3 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme Billy Elliot Melvin Burgess Chapter 6: Billy visits his friend, Michael, who is wearing his sister’s clothes and lipstick. Billy tells Michael that he wants to be a ballet dancer in London. They both realise that they are different from the other boys of their age in their town. Chapter 7: Billy starts practising for a ballet audition and gets very nervous as it gets closer. Jackie and Tony have a fight and Tony runs away. One night Billy sees his dead mother, Sarah, and feels that she wants him to dance at the audition. Chapter 8: Tony attacks a policeman’s horse and ends up in jail. Jackie and Billy go to court to fetch him and Billy misses his audition. Mrs Wilkinson gets furious and tells the Elliots what has happened. Tony can’t believe that his brother wants to be a ballet dancer. About the author Billy Elliot is originally a British film (2000) directed by Chapter 9: Michael, in a dancing skirt, and Billy, in his ballet Stephen Daldry. The screenplay was written by Lee Hall shoes, stand in the boxing ring. While Billy is showing his and then adapted as a novel by Melvin Burgess, who is a friend some ballet moves, his father enters the hall and popular and prolific writer of young adult fiction. Some of sees them. Billy jumps, spins and dances for his father, his works are Junk, Bloodtide and Doing It. who leaves the hall upset but very surprised with what he has seen. -

Drama Movies

Libraries DRAMA MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 42 DVD-5254 12 DVD-1200 70's DVD-0418 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 8 1/2 DVD-3832 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 127 Hours DVD-8008 8 Mile DVD-1639 1776 DVD-0397 9th Company DVD-1383 1900 DVD-4443 About Schmidt DVD-9630 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Accused DVD-6182 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 1 Ace in the Hole DVD-9473 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1 Across the Universe DVD-5997 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adam Bede DVD-7149 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adjustment Bureau DVD-9591 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1 Admiral DVD-7558 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 5 Adventures of Don Juan DVD-2916 25th Hour DVD-2291 Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert DVD-4365 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 Advise and Consent DVD-1514 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 Affair to Remember DVD-1201 3 Women DVD-4850 After Hours DVD-3053 35 Shots of Rum c.2 DVD-4729 c.2 Against All Odds DVD-8241 400 Blows DVD-0336 Age of Consent (Michael Powell) DVD-4779 DVD-8362 Age of Innocence DVD-6179 8/30/2019 Age of Innocence c.2 DVD-6179 c.2 All the King's Men DVD-3291 Agony and the Ecstasy DVD-3308 DVD-9634 Aguirre: The Wrath of God DVD-4816 All the Mornings of the World DVD-1274 Aladin (Bollywood) DVD-6178 All the President's Men DVD-8371 Alexander Nevsky DVD-4983 Amadeus DVD-0099 Alfie DVD-9492 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Amarcord DVD-4426 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul c.2 DVD-4725 c.2 Amazing Dr. -

Geography. a Level Preparation Pack

geography. A Level Preparation Pack Overview The Geography department looks forward to familiarise yourself with over the next few to welcoming you in September. We have months to help you make the transition to A an experienced teacher of Geography who level. will help you make the transition to the much greater demands of A level Geography and give you a lifelong love of the subject. We have collated a range of resources for you Claire Morgan Head of Geography What is Geography? The course is split into Human and Physical Geography and you will study 3 topics in each. Human Geography Global systems and Global Governance: Documentaries • Rotten (Netflix documentary) • Capitalism: A Love Story, Michael Moore (2009) Changing Places: Films • The Full Monty, Peter Cattaneo (1997) • Billy Elliot, Stephen Daldry (2000) • Brassed Off, Mark Herman (1996) • There Will Be Blood, Paul Thomas Anderson (2007) • 8 Mile, Curtis Hanson (2002) Websites • www.datashine.org.uk • https://www.gov.org.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2015 Population and the Environment: Documentaries • No Sex Please We’re Japanese – BBC Two • Megacities – BBC One • Planet Earth – David Attenborough • Our Planet – David Attenborough • Global Population Growth, Box by Box. – Hans Rosling Gapminder Films • Slumdog Millionaire, Danny Boyle (2008) Books • Guns, Germs and Steel, the Fates of Human Societies – Jared Diamond. Physical Geography Water and Carbon Cycles: Documentaries • Chasing Coral (Netflix documentary) • The Fate of Carbon, Changing Seas - Season 9, Episode 3 • The Disarming Case to Act Right Now, Climate Change – Greta Thunberg, Ted Talk. • Before the Flood – Leonardo DiCaprio • An Inconvenient Truth – Al Gore • An Inconvenient Sequel – Al Gore Book • No One Is Too Small To Make A Difference – Greta Thunberg Coastal systems and landscapes: Documentaries. -

Billy Elliot– Extra

S CHOLASTIC ELT READERS A FREE RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS! Billy Elliot – Extra Level 1 This level is suitable for students who have been learning English for at least a year and up to two years. It corresponds with the Common European Framework level A1. Suitable for users of CLICK magazine. SYNOPSIS the story is told by Jackie, Billy’s dad, and one part is told by Billy Elliot comes from a mining family. His mother died two Tony, Billy’s brother. Look at the Contents page – the title of years ago. It’s now 1984, and most of the miners, like Billy’s dad each chapter tells you who is telling that part of the story. and brother, are on strike. There’s no money coming in and life The writer Lee Hall thinks the miners’ strike of 1984 is a very is difficult. Billy, meanwhile, dreams about dancing, and, by important time in recent British history. He wanted to explore chance, he joins the local ballet class. The teacher sees at once the different characters and ideas involved in this political that he’s special. When Billy’s dad finds out, he’s angry. Ballet is struggle. But he also wanted a good story. for girls! But Billy carries on in secret and his teacher enters him When Elton John saw the film, it reminded him of his own for the Royal Ballet School. Then the police arrest Billy’s brother. life as a talented young pianist with a difficult father. He worked Instead of going to the audition, Billy has to watch his brother on the musical version of the story with Lee Hall and the film’s in court. -

Teaching Diversity with Film

Teaching Diversity with Film The Illinois and United States Constitutions guarantee that all people are to be treated as equals under the law. A wide range of anti-discrimination laws protect people including specific provisions against discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, ancestry, age, sex, marital status, disability, sexual orientation, military service or unfavorable discharge from military service. These laws extend protections to everyone in our increasingly diverse nation. We can be proud that our equal rights laws and acceptance of diversity stands as an example to other governments and societies. To enhance diversity discussions in classrooms and communities, here is a partial list of films that can be used as tools to generate discussions. Please note: Some have adult content. Teachers should review a selected movie before using in class. A Day Without A Mexican A Patch of Blue A Time to Kill Akeelah and the Bee Amistad Babe Beauty and the Beast Bend it like Beckham Billy Elliot Birth of a Nation Boys Don’t Cry Boyz 'N the Hood Brokeback Mountain Crash Dances With Wolves David and Lisa Do the Right Thing Fried Green Tomatoes Gandhi Ghosts of Mississippi Glory Hiroshima Maiden In the Heat of the Night Malcolm X Mississippi Burning Monsoon Wedding Munich My Left Foot Osama Patch Adams Philadelphia Pokahontas Radio Rain Man Real Women have Curves Remember the Titans Roots Save the Last Dance Schildler’s List Shrek Snow White Sophie’s Choice Spanglish The Color Purple The Gods Must Be Crazy The Hiding Place The Joy Luck Club Thumbelina To Kill a Mockingbird Transamerica West Side Story Wizard of Oz Young Frankenstein Visit the ABA for more diversity film titles http://www.abanet.org/publiced/resources/diversity_ae.html DIVERSITY MOVIE REVIEW ACTIVITY - View one of the movies on the list provided and write a brief review. -

THEATRE in ENGLAND 2012-13 UNIVERSITY of ROCHESTER Mara Ahmed

THEATRE IN ENGLAND 2012-13 UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Mara Ahmed The Master and Margarita Barbican Theatre 12/28/12 Based on Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel, this adaptation by Simon McBurney is as inventive and surprising as the book’s storyline. Satan disguised as Professor Woland visits Stalinist Russia in the 1930s. He and his violent retinue use their black magic and death prophesies to dispose of people and take over their apartments; most villainy and betrayal in the play is in fact motivated by the acquisition of apartment space. Bulgakov is satirizing the restriction of private space in Stalin’s Russia but buildings are also a metaphor for the structure of society as a whole. Rooms are demarcated by light beams, in the constantly changing set design, in order to emphasize relative boundaries and limits. The second part of the play focuses on Margarita and her lover, a writer who has just finished a novel about the complex relationship between Pontius Pilate (the Roman procurator of Judaea) and Yeshua ha-Nostri (Jesus, a wandering philosopher). Margarita calls him the Master on account of his brilliant literary chef d’oeuvre. She is devoted to him. However, the Master’s novel is ridiculed by the Soviet literati and after being denounced by a neighbor, he is taken into custody and ends up at a lunatic asylum. The parallels between his persecution and that of his principal character, Jesus, are brought into relief by constant shifts in time and place, between Moscow and Jerusalem. Margarita makes a bargain with Satan on the night of his Spring Ball, which she agrees to host, and succeeds in saving the Master. -

‚Gutes' Theater

VS PLUS Zusatzinformationen zu Medien des VS Verlags ‚Gutes’ Theater Theaterfinanzierung und Theaterangebot in Großbritannien und Deutschland im Vergleich 2011 | Erstauflage Anhang Tabellen [Text eingeben] www.viewegteubner.de www.vs -verlag.de Inhaltsverzeichnis Tab. 1: Internationale Definitionen von Kultur, Kultursektor, Kulturindustrien....................................4 Tab. 2: Kulturfinanzierung, GB, 1998/99, in ₤ Mio. und %...................................................................5 Tab. 3: Zentralstaatliche Kulturförderung in GB, 1998/99, in ₤ Mio. und %......................................... 5 Tab. 4: Anteil Kultursponsoring am BIP, D vs. GB, 1999-2007............................................................5 Tab. 5 Production categories , TMA (Beschreibung der Sparten für die Umfrage), ab 1993 ...............6 Tab. 6a: Production categories , SOLT .................................................................................................... 7 Tab. 6b: Sub genres und other production criteria , SOLT ......................................................................7 Tab. 7: Verteilung der deutschen Theater nach Träger, 1990-2005 .......................................................8 Tab. 8: Verteilung Rechtsträger und -formen der deutschen öffentlichen Theaterunternehmen............ 8 Tab. 9: Londoner Theater (SOLT-Mitgliedschaft).................................................................................9 Tab. 10: Wichtigste Londoner Theater, A-Z, Sitzplatzkapazitäten, Eigentümer/ Betreiber.................. -

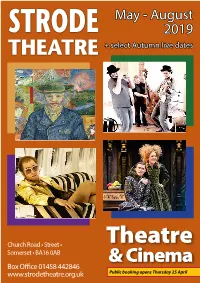

May - August 2019 + Select Autumn Live Dates

May - August 2019 + select Autumn live dates Church Road • Street • Theatre Somerset • BA16 0AB & Cinema Box Office 01458 442846 www.strodetheatre.org.uk Public booking opens Thursday 25 April Welcome to our brochure for Summer season ...with some treats from the autumn season too... WELCOME Summer is almost upon us already. Last year, the weather was so hot that - together with the World Cup - it turned out that not too many folk wanted to came out and play at the theatre or cinema! I know we were not alone -many theatres and visitor attractions really ‘took a hit’ last year. The summer before, on the other hand, we had a ‘bumper’ summer season; such is the nature of the game! Without knowing how the Look out for the Family weather is going to turn out, it is difficult to programme appropriately Friendly logo. –so we have to hedge our bets! This season, I hope you are able to enjoy something from our wide programme of films, live broadcasts and live This indicates films, shows shows. So that you can enjoy the warm evenings as well as top qulaity films, I’m very pleased that we have partnered once again with Alfred and live transmissions that Gillett Trust and now also with Clarks Village to give you yet another are appropriate for all ages Outdoor Cinema season! (see page 40) and fun for all the family. I’m also very glad to be able to tell you that we have just received a small award from Film Hub South West - a regional division of the British Film Institute (BFI) - for our British, international and independent film programme in 2018.