On-Demand Grocery Disruption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Response: Just Eat Takeaway.Com N. V

NON- CONFIDENTIAL JUST EAT TAKEAWAY.COM Submission to the CMA in response to its request for views on its Provisional Findings in relation to the Amazon/Deliveroo merger inquiry 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1. In line with the Notice of provisional findings made under Rule 11.3 of the Competition and Markets Authority ("CMA") Rules of Procedure published on the CMA website, Just Eat Takeaway.com N.V. ("JETA") submits its views on the provisional findings of the CMA dated 16 April 2020 (the "Provisional Findings") regarding the anticipated acquisition by Amazon.com BV Investment Holding LLC, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Amazon.com, Inc. ("Amazon") of certain rights and minority shareholding of Roofoods Ltd ("Deliveroo") (the "Transaction"). 2. In the Provisional Findings, the CMA has concluded that the Transaction would not be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition ("SLC") in either the market for online restaurant platforms or the market for online convenience groceries ("OCG")1 on the basis that, as a result of the Coronavirus ("COVID-19") crisis, Deliveroo is likely to exit the market unless it receives the additional funding available through the Transaction. The CMA has also provisionally found that no less anti-competitive investors were available. 3. JETA considers that this is an unprecedented decision by the CMA and questions whether it is appropriate in the current market circumstances. In its Phase 1 Decision, dated 11 December 20192, the CMA found that the Transaction gives rise to a realistic prospect of an SLC as a result of horizontal effects in the supply of food platforms and OCG in the UK. -

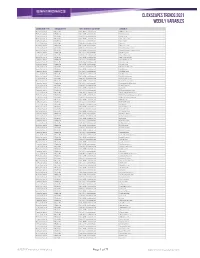

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Mckinsey on Finance

McKinsey on Finance Perspectives on Corporate Finance and Strategy Number 59, Summer 2016 2 5 11 Bracing for a new era of The ‘tech bubble’ puzzle How a tech unicorn lower investment returns creates value 17 22 Mergers in the oil ‘ We’ve realized a ten-year patch: Lessons from strategy goal in one year’ past downturns McKinsey on Finance is a Editorial Board: David Copyright © 2016 McKinsey & quarterly publication written by Cogman, Ryan Davies, Marc Company. All rights reserved. corporate-finance experts Goedhart, Chip Hughes, and practitioners at McKinsey Eduardo Kneese, Tim Koller, This publication is not intended & Company. This publication Dan Lovallo, Werner Rehm, to be used as the basis offers readers insights into Dennis Swinford, Marc-Daniel for trading in the shares of any value-creating strategies and Thielen, Robert Uhlaner company or for undertaking the translation of those any other complex or strategies into company Editor: Dennis Swinford significant financial transaction performance. without consulting appropriate Art Direction and Design: professional advisers. This and archived issues of Cary Shoda McKinsey on Finance are No part of this publication Managing Editors: Michael T. available online at McKinsey may be copied or redistributed Borruso, Venetia Simcock .com, where selected articles in any form without the prior written consent of McKinsey & are also available in audio Editorial Production: Company. format. A series of McKinsey Runa Arora, Elizabeth Brown, on Finance podcasts is Heather Byer, Torea Frey, available on iTunes. Heather Hanselman, Katya Petriwsky, John C. Sanchez, Editorial Contact: Dana Sand, Sneha Vats McKinsey_on_Finance@ McKinsey.com Circulation: Diane Black To request permission to Cover photo republish an article, send an © Cozyta/Getty Images email to Quarterly_Reprints@ McKinsey.com. -

Online Transportation Price War: Indonesian Style

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Klaipeda University Open Journal Systems SAKTI HENDRA PRAMUDYA ONLINE TRANSPORTATION PRICE WAR: INDONESIAN STYLE ONLINE TRANSPORTATION PRICE WAR: INDONESIAN STYLE Sakti Hendra Pramudya1 Universitas Bina Nusantara (Indonesia), University of Pécs (Hungary) ABStrAct thanks to the brilliant innovation of the expanding online transportation companies, the Indonesian people are able to obtain an affor- dable means of transportation. this three major ride-sharing companies (Go-Jek, Grab, and Uber) provide services which not only limited to transportation service but also providing services for food delivery, courier service, and even shopping assistance by utili- zing gigantic armada of motorbikes and cars which owned by their ‘driver partners’. these companies are competing to gain market share by implementing the same strategy which is offering the lowest price. this paper would discuss the Indonesian online trans- portation price war by using price comparison analysis between three companies. the analysis revealed that Uber was the winner of the price war, however, their ‘lowest price strategy’ would lead to their downfall not only in Indonesia but in all of South East Asia. KEYWOrDS: online transportation companies, price war, Indonesia. JEL cODES: D40, O18, O33 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15181/rfds.v29i3.2000 Introduction the idea of ride-hailing was unfamiliar to Indonesian people. Before the inception (and followed by the large adoption) of smartphone applications in Indonesia, the market of transportation service was to- tally different. the majority of middle to high income Indonesian urban dwellers at that time was using the conventional taxi as their second option of transportation after their personal car or motorbike. -

Just Eat/Hungryhouse Appendices and Glossary to the Final Report

Anticipated acquisition by Just Eat of Hungryhouse Appendices and glossary Appendix A: Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Appendix B: Delivery Hero and Hungryhouse group structure and financial performance Appendix C: Documentary evidence relating to the counterfactual Appendix D: Dimensions of competition Appendix E: The economics of multi-sided platforms Appendix F: Econometric analysis Glossary Appendix A: Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Terms of reference 1. On 19 May 2017, the CMA referred the anticipated acquisition by Just Eat plc of Hungryhouse Holdings Limited for an in-depth phase 2 inquiry. 1. In exercise of its duty under section 33(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (the Act) the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) believes that it is or may be the case that: (a) arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation, in that: (i) enterprises carried on by, or under the control of, Just Eat plc will cease to be distinct from enterprises carried on by, or under the control of, Hungryhouse Holdings Limited; and (ii) the condition specified in section 23(2)(b) of the Act is satisfied; and (b) the creation of that situation may be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition within a market or markets in the United Kingdom for goods or services, including in the supply of online takeaway ordering aggregation platforms. 2. Therefore, in exercise of its duty under section 33(1) of the Act, the CMA hereby makes -

Meituan 美團 (The “Company”) Is Pleased to Announce the Audited Consolidated Results of the Company for the Year Ended December 31, 2020

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. (A company controlled through weighted voting rights and incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock code: 3690) ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE RESULTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The Board of Directors (the “Board”) of Meituan 美團 (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the audited consolidated results of the Company for the year ended December 31, 2020. These results have been audited by the Auditor in accordance with International Standards on Auditing, and have also been reviewed by the Audit Committee. In this announcement, “we,” “us” or “our” refers to the Company. KEY HIGHLIGHTS Financial Summary Unaudited Three Months Ended December 31, 2020 December 31, 2019 As a As a percentage percentage Year-over- Amount of revenues Amount of revenues year change (RMB in thousands, except for percentages) Revenues 37,917,504 100.0% 28,158,253 100.0% 34.7% Operating (loss)/profit (2,852,696) (7.5%) 1,423,860 5.1% (300.3%) (Loss)/profit for the period (2,244,292) (5.9%) 1,460,285 5.2% (253.7%) Non-IFRS Measures: Adjusted EBITDA (589,128) (1.6%) 2,178,650 7.7% (127.0%) Adjusted net (loss)/profit (1,436,520) (3.8%) 2,270,219 8.1% (163.3%) Year Ended December 31, 2020 -

Southeast Asia New Economy

July 29, 2020 Strategy Focus Southeast Asia New Economy Understanding ASEAN's Super Apps • Grab and Gojek started as ride hailing companies and have expanded to food and parcel delivery, e-wallet and other daily services, solidifying their "Super App" status in ASEAN. • Bloomberg reported in April 2019 that both companies had joined the "decacorn" ranks, valuing Grab at US$14bn and Gojek at US$10bn. • Both Grab and Gojek have stated their intentions to list by 2023/24. Building on our June 14, 2020 ASEAN Who’s Who report, we take a closer look at Grab and Gojek, two prominent Southeast Asian app providers that achieved Super App status. Practicality vs. time spent: The ASEAN population spends 7-10 hours online daily (Global Web Index as of 3Q19), of which 80% is on social media and video streaming sites. While ride hailing services command relatively low usage hours, the provision of a reliable alternative to ASEAN's (except for Singapore's) underdeveloped public transport has made both "must own" apps. Based on June 2020 App Annie data, 29% and 27% of the ASEAN population had downloaded the Grab and Gojek apps, respectively. Merchant acquisition moving to center stage: A price war and exorbitant incentives/ subsidies characterized customer acquisition strategies until Grab acquired Uber’s Southeast Asian operations in March 2018. We now see broader ride hailing pricing discipline. Grab and Gojek have turned to merchant acquisition as their focus shifts to online food delivery business (and beyond). ASEAN TAMs for ride hailing of US$25bn and online food delivery of US$20bn by 2025E: Our sector models focus on ASEAN’s middle 40% household income segment, which we see as the target audience for both businesses. -

Amazing Takeaway Experience

DELIVERY HERO FACT SHEET On a mission to create an amazing In May 2011, CEO Niklas Östberg co-founded Delivery Hero with takeaway the mission to provide an inspirational, personalized and experience simple way of ordering food. $ KEY 弛吐ſ NUMBERS Based in Berlin, Delivery Hero is the leading global online food ordering and VARIETY DIVERSITY INVESTMENTS delivery marketplace. We Delivery Hero operates online To date over €1.4 billion has been employ 6,000+ staff plus marketplaces for food order- +6000 staff from invested into Delivery Hero. The ing and also operates its own company’s largest shareholders thousands of employed food delivery primarily in 50+ +60 nationalities are Naspers, Insight Venture Part- riders across 40+ countries, high-density urban areas around ners, Luxor Capital Group (each of with 35 number one market the world, which allows Delivery is employed in them represented in the superviso- positions. We maintain Hero to include offerings from Berlin HQ alone ry board), and Rocket Internet (no the largest food network in curated restaurants that do not board seat). the world with more than offer food delivery themselves. 150.000 restaurant partners. In 2016 we processed +170 million orders. In May 2017 BUSINESS MODEL we processed +1m order Search 1 on a single day for the first benefit, among other, from time. CUSTOMERS • an inspirational selection of restaurants and dishes • a great takeaway experience driven by easy usage, short HOUSE OF Order 2 delivery times and plenty of individual order options BRANDS Since 2011, Delivery Hero benefit, among others, from grew significantly through RESTAURANTS • access to a large customer a combination of organic base growth and acquisitions. -

Data Challenges in an Acquisition Based World

07 June 2018 Data Challenges in an acquisition based world (or how to click a Data Lake together with AWS) Daniel Manzke CTO Restaurant Vertical @ Delivery Hero © 2018, Amazon Web Services, Inc. or its affiliates. All rights reserved. How do you tackle the challenges of reporting and data quality in a company with a model of local and centralized entities? We will talk about the evolution of Data in Delivery Hero from Data Warehouse to a Data Lake oriented Architecture and will show you how you can click your own Data Lake together with the help of AWS. © 2018, Amazon Web Services, Inc. or its affiliates. All rights reserved. We are an Online Food Ordering and Delivery Marketplace History 2008 Niklas started OnlinePizza in Sweden 2010 Lieferheld launched 2011 HungryHouse joins 2012 OnlinePizza Norden joins 2014 PedidosYa, pizza.de and Baedaltong joins 2015 Talabat, Yemeksepti and Foodora joins 2016 foodpanda joins IPO, M&A, ... Hyper-Local 2016 Customer Experience - Data USER ● The RightRESTAURANT Food 3 Receive Cook Order ○ Search, Recommendations, 4 2 Vouchers, Premium Placements Customer Order 1 Search ● OrderReceived Placement (TBU) ○ Time to Order ○ Estimated Delivery Time ○ Payment Method Deliver 5 ● After Order 6 ○ Reviews, Ratings, Complaints Customer Order Eat ○ Where is myReceived food? (TBU) ○ Reorder Rate “Understand the whole cycle” Order delivery - Data USER RESTAURANT Receive Cook ● Availability Order 3 4 ○ Online, Open, Busy,2 ... Search Customer Order ● 1Cooking Received (TBU) ○ Preparation Time ○ Items Unavailable ● Delivery Deliver 5 ○ Driving Time ○ Driver Shifts6 ○ Delivered?!Eat Customer Order Received (TBU) RESTAURANT “Tons of Data to collect” DRIVER We are an Online Food Ordering and Delivery Marketplace USER RESTAURANT Receive Cook Order 3 4 2 Search Customer Order 1 Received (TBU) Deliver 5 6 Eat Customer Order Received (TBU) RESTAURANT DRIVER KPIs, Reporting, .. -

At the Global Food Safety Conference 2018

+17TH EDITION GFSC 1,200 DELEGATES 2018 CONTENT in numbers 86% +80% 53 of delegates rank this event plan to join us better than other countries The Global Food Safety Conference � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4 Mike Taylor, Former FDA Deputy Commissioner � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 16 5 again in 2019 comparable events Programme at a Glance � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5 Xiaoqun He, Deputy Director General of Registration DAYS Department, CNCA � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 16 of sessions, Michel Leporati, Executive Secretary, ACHIPIA meetings and DAY 1: TUESDAY 6TH MARCH 2018 events (Agencia Chilena para la Calidad e Inocuidad Alimentaria) � � � 17 PRE-CONFERENCE SESSION: Dr. Stephen Ostroff, Deputy Commissioner, Office of Foods GFSI & YOU & Veterinary Medicine, U.S. Food & Drug Administration, FDA � � � � 17 Katsuki Kishi, General Manager, Quality Management Depart- Jason Feeney, CEO, FSA � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 17 ment, ÆON Retail Co., Ltd. � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 Bill Jolly, Chief Assurance Strategy Officer, New Zealand 8 8 3 4 3rd Andy Ransom, CEO, Rentokil Initial � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 Ministry for Primary Industries � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 17 65 36 Special Tech Discovery GFSI award iteration Peter Freedman, Managing Director, The Consumer Speakers Exhibitors -

Food Delivery Platforms: Will They Eat the Restaurant Industry's Lunch?

Food Delivery Platforms: Will they eat the restaurant industry’s lunch? On-demand food delivery platforms have exploded in popularity across both the emerging and developed world. For those restaurant businesses which successfully cater to at-home consumers, delivery has the potential to be a highly valuable source of incremental revenues, albeit typically at a lower margin. Over the longer term, the concentration of customer demand through the dominant ordering platforms raises concerns over the bargaining power of these platforms, their singular control of customer data, and even their potential for vertical integration. Nonetheless, we believe that restaurant businesses have no choice but to embrace this high-growth channel whilst working towards the ideal long-term solution of in-house digital ordering capabilities. Contents Introduction: the rise of food delivery platforms ........................................................................... 2 Opportunities for Chained Restaurant Companies ........................................................................ 6 Threats to Restaurant Operators .................................................................................................... 8 A suggested playbook for QSR businesses ................................................................................... 10 The Arisaig Approach .................................................................................................................... 13 Disclaimer .................................................................................................................................... -

Delivery Hero Geschäftsbericht 2020

ALWAYS DELIVERING AN AMAZING EXPERIENCE ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ALWAYS DELIVERING CONTENT AN AMAZING COMPANY 3 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT 85 At a Glance 3 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 86 EXPERIENCE Our Values 5 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Letter from the CEO 6 Other Comprehensive Income 87 Management and Team 8 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 88 Report of the Supervisory Board 9 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 90 Corporate Governance 14 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 91 Non-financial Report for the Group 35 Responsibility Statement 153 Investor Relations 49 Independent Auditorʼs Report 154 Limited Assurance Report of the Independent Auditor 161 COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT 52 FURTHER INFORMATION 163 Group Profile 53 Economic Report 56 GRI Content Index 164 Risk and Opportunity Report 67 Financial Calendar 2021 169 Outlook 79 Imprint 169 Supplementary Management Report to the Disclaimer and further Notices 170 Separate Financial Statements 81 Other Disclosures 84 Use our interactive table of contents. You will be taken directly to the relevant page. DELIVERY HERO AT A GLANCE ORDERS 2020: GMV 1,304.1 2020: MILLION EUR MILLION 12,360.9 BACK 2019: 2019: +96 % 666.0 +66 % 7,435.4 FORWARD PREVIOUS PAGE SEARCH TOTAL SEGMENT ADJ. EBITDA/GMV HOME REVENUE IN % 2020: EUR MILLION 2,836.2 −8 −6 −4 −2 0 2020: 2019: −4.6 +95 % 2019: −5.8 1,455.7 +1.2 PP EUROPE Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Montenegro, +51 % Norway,