Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Gamma in Place of Digamma in Ancient Greek

Mnemosyne (2020) 1-22 brill.com/mnem The Use of Gamma in Place of Digamma in Ancient Greek Francesco Camagni University of Manchester, UK [email protected] Received August 2019 | Accepted March 2020 Abstract Originally, Ancient Greek employed the letter digamma ( ϝ) to represent the /w/ sound. Over time, this sound disappeared, alongside the digamma that denoted it. However, to transcribe those archaic, dialectal, or foreign words that still retained this sound, lexicographers employed other letters, whose sound was close enough to /w/. Among these, there is the letter gamma (γ), attested mostly but not only in the Lexicon of Hesychius. Given what we know about the sound of gamma, it is difficult to explain this use. The most straightforward hypothesis suggests that the scribes who copied these words misread the capital digamma (Ϝ) as gamma (Γ). Presenting new and old evidence of gamma used to denote digamma in Ancient Greek literary and documen- tary papyri, lexicography, and medieval manuscripts, this paper refutes this hypoth- esis, and demonstrates that a peculiar evolution in the pronunciation of gamma in Post-Classical Greek triggered a systematic use of this letter to denote the sound once represented by the digamma. Keywords Ancient Greek language – gamma – digamma – Greek phonetics – Hesychius – lexicography © Francesco Camagni, 2020 | doi:10.1163/1568525X-bja10018 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. from Brill.com09/30/2021 01:54:17PM via free access 2 Camagni 1 Introduction It is well known that many ancient Greek dialects preserved the /w/ sound into the historical period, contrary to Attic-Ionic and Koine Greek. -

The Greek Alphabet Sight and Sounds of the Greek Letters (Module B) the Letters and Pronunciation of the Greek Alphabet 2 Phonology (Part 2)

The Greek Alphabet Sight and Sounds of the Greek Letters (Module B) The Letters and Pronunciation of the Greek Alphabet 2 Phonology (Part 2) Lesson Two Overview 2.0 Introduction, 2-1 2.1 Ten Similar Letters, 2-2 2.2 Six Deceptive Greek Letters, 2-4 2.3 Nine Different Greek Letters, 2-8 2.4 History of the Greek Alphabet, 2-13 Study Guide, 2-20 2.0 Introduction Lesson One introduced the twenty-four letters of the Greek alphabet. Lesson Two continues to present the building blocks for learning Greek phonics by merging vowels and consonants into syllables. Furthermore, this lesson underscores the similarities and dissimilarities between the Greek and English alphabetical letters and their phonemes. Almost without exception, introductory Greek grammars launch into grammar and vocabulary without first firmly grounding a student in the Greek phonemic system. This approach is appropriate if a teacher is present. However, it is little help for those who are “going at it alone,” or a small group who are learning NTGreek without the aid of a teacher’s pronunciation. This grammar’s introductory lessons go to great lengths to present a full-orbed pronunciation of the Erasmian Greek phonemic system. Those who are new to the Greek language without an instructor’s guidance will welcome this help, and it will prepare them to read Greek and not simply to translate it into their language. The phonic sounds of the Greek language are required to be carefully learned. A saturation of these sounds may be accomplished by using the accompanying MP3 audio files. -

Ebook Download the New Testament Ebook Free Download

THE NEW TESTAMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicholas King | 655 pages | 01 Dec 2004 | Kevin Mayhew Ltd | 9781844173242 | English | Suffolk, United Kingdom The New Testament PDF Book The first translation was made by at least the 3rd century into the Sahidic dialect cop sa. Word UK Ltd. Although a number of Christians have thought that church councils determined what books were to be included in the biblical canons, a more accurate reflection of the matter is that the councils recognized or acknowledged those books that had already obtained prominence from usage among the various early Christian communities. Introduction to the New Testament, Volume 2. Main article: Canonical gospels. They contain similar accounts of the events in Jesus's life and his teaching, due to their literary interdependence. Resources for Biblical Study. Start Publishing LLC. For full treatment, see biblical literature: Conditions aiding the formation of the canon. In many respects it was merely a revision of the Old Latin. No Codex Siniaticus. A brief summary of the acts was read at and accepted by the Council of Carthage and the Council of Carthage Jehovah's Witnesses Latter Day Saint movement. See media help. Ehrman , "These scribal additions are often found in late medieval manuscripts of the New Testament, but not in the manuscripts of the earlier centuries. A text-type referred to as the " Caesarean text-type " and thought to have included witnesses such as Codex Koridethi and minuscule , can today be described neither as "Caesarean" nor as a text-type as was previously thought. For this reason, the Bohairic translation can be helpful in the reconstruction of the early Greek text of the New Testament. -

Inside This Issue: Pisces Is the Last Sign of the Zodiac

www.greekamericancare.org 847 Wheeling, IL 60090 220 N. First Street - 459 THE - 8700 GREEK-AMERICAN TIMES LOEFFLER, M. 03/05 PETRAKIS,S. 03/06 MANOLAS, E. 03/09 MARLANTIS,A. 03/15 LATSON, A. 03/15 LANZILLOTTI,G. 03/28 Inside this issue: Pisces is the last sign of the zodiac. People who are born between February 19th to Special Points of Interest / Birthdays th March 20 are said to be born Pisces. The ruling planet of Activity Happenings Pisces is Neptune. They are 25th of March ~ Greek Independence Day the most emphatic sign of the zodiac and are deeply patient 25th of March—the Annunciation and gentle. They are mostly GARCC—15-Year Anniversary generous and emotional and happen to be quite popular. Saint Patrick’s Day National Women’s History These are people who value human relationships above everything and give a lot of importance to A Special Thank you human feelings. This sign is represented by two National Women’s Month fishes that are swimming at the opposite direction. As per the ancient Greek mythology, the fishes are Volunteers Needed in reality Eros and his mother Aphrodite; who were trying to flee from the clutches of the ‘Typon’, the Life Enrichment Calendar Lord of Fire. 1 Activity happenings … Welcome all to our March issue of the Greek American Times and welcome Spring. First, we would like to share some of our February activities which were plenty and very joyful. Like every month, many of our friends paid us a visit. The Greek American The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Uprising Rehabilitation and Care Centre Women’s Auxiliary hosted a lovely Valentine’s Day Social and was a successful war of independence waged by the Greek revolutionaries between 1821 and 1832 gave us cards, balloons, delicious cake and ice-cream sundaes. -

What Scriptures Or Bible Nearest to Original Hebrew Scriptures? Anong Biblia Ang Pinaka-Malapit Sa Kasulatang Hebreo

WHAT BIBLE TO READ WHAT SCRIPTURES OR BIBLE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES? ANONG BIBLIA ANG PINAKA-MALAPIT SA KASULATANG HEBREO KING JAMES BIBLE OLD TESTAMENT IS THE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES BECAUSE THE OLD TESTAMENT WAS DIRECTLY TRANSLATED FROM HEBREW COLUMN OF ORIGENS’S HEXAPLA. KING JAMES BIBLE ALSO WAS COMPARED TO NEWLY FOUND DEAD SEA SCROLL WITH CLOSE AND VERY NEAR TRANSLATION TO THE TEXT FOUND ON DEAD SEA SCROLL ni Isagani Datu-Aca Tabilog WHAT SCRIPTURES OR BIBLE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES? KING JAMES BIBLE OLD TESTAMENT IS THE NEAREST TO ORIGINAL HEBREW SCRIPTURES BECAUSE THE OLD TESTAMENT WAS DIRECTLY TRANSLATED FROM HEBREW COLUMN OF ORIGENS’S HEXAPLA. KING JAMES BIBLE ALSO WAS COMPARED TO NEWLY FOUND DEAD SEA SCROLL WITH CLOSE AND VERY NEAR TRANSLATION TO THE TEXT FOUND ON DEAD SEA SCROLL Original King Iames Bible 1611 See the Sacred Name YAHWEH in modern Hebrew name on top of the Front Cover 1 HEXAPLA FIND THE DIFFERENCE OF DOUAI BIBLE VS. KING JAMES BIBLE Genesis 6:1-4 Genesis 17:9-14 Isaiah 53:8 Luke 4:17-19 AND MANY MORE VERSES The King James Version (KJV), commonly known as the Authorized Version (AV) or King James Bible (KJB), is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England begun in 1604 and completed in 1611. First printed by the King's Printer Robert Barker, this was the third translation into English to be approved by the English Church authorities. The first was the Great Bible commissioned in the reign of King Henry VIII, and the second was the Bishops' Bible of 1568. -

A Α B Β Γ Γ ∆ Δ E Ε Ϝ Ϝ Z Ζ H Η Θ Θ I Ι K Κ Λ Λ M Μ N Ν Ξ Ξ O O Π Π Ϙ Ϙ P Ρ

Chapter 1 _______________________________ The Greek Alphabet _____________________ 1.1 The pronunciation of Koine (koy-nay) (Common) Greek at the time of the New Testament is a matter of debate. The system given here is an adaptation of the pronunciation sometimes referred to as Erasmian, recommended by the Classical Association. 1.2 The Letters and their sounds Pronunciation Capital Small κoινη modern Greek Alpha A α a as in cat ah as in father Beta B β b as in big v as in vim Gamma (1) Γ γ g as in get "y" or "gyh" Delta ∆ δ d as in dog th as in then Epsilon (2) E ε e as in get e as in get Vau or Digamma (3) Ϝ ϝ Zeta Z ζ dz as in adze z as in zoo Eta H η ey as in grey ee as in see Theta Θ θ th as in thin th as in thin Iota (4) I ι i as in it ee as in see Kappa K κ k as in kick k as in kick Lambda Λ λ l as in let l as in let Mu M µ m as in man m as in man Nu N ν n as in no n as in no Xi Ξ ξ x as in taxi x as in taxi Omicron (5) O o o as in got or as in lord Pi Π π p as in pie p as in pie Koppa (6) Ϙ ϙ k as in kick Rho (7) P ρ r as in red r as in very Sigma (8) Σ σ or ς s as in sit s as in sit Tau T τ t as in tag t as in tag Upsilon (9) Y υ u as in put ee as in see Phi Φ φ f as in fie f as in fie Chi (10) X χ ch as in loch hu as in human Psi (11) Ψ ψ ps as in tips ps as in tips Omega (12) Ω ω o as in home or as in lord Notes : (1) Gamma : when gamma is combined with other gutturals, γγ , γκ , γξ , γχ the γ is pronounced as the "n" in sing, ink, sinks, etc. -

Greece in Modern Times (An Annotated Bibliography of Works Published in English in 22 Academic Disciplines During the Twentieth Century)

Published in: S. Constantinidis (ed.) Greece in Modern Times (An Annotated Bibliography of Works Published in English in 22 Academic Disciplines During the Twentieth Century). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press (1999), pp. 441-474. Selected Titles on Language and Linguistics Prepared by Brian D. Joseph, The Ohio State University INTRODUCTION This bibliography as a whole has as its main focus Greece of the twentieth century. As far as the Greek language and its study, i.e. the field of Greek linguistics, are concerned, however, there is nothing particularly special about the twentieth century. To be sure, the current century has witnessed a number of changes in the Greek language, mostly in the area of its lexical resources as Greek has borrowed, adapted, and absorbed large numbers first of French words and more recently of English words. However, the essential character of Modern Greek, as opposed to significantly earlier stages of the language such as the Greek of the New Testament or Ancient Greek, was formed by no later than the seventeenth century, and most likely even earlier. In surveying the literature produced over the past forty to sixty years on Modern Greek per se, therefore, one must necessarily take into account works that deal with pre-twentieth century Greek. Indeed, it can be argued that Modern Greek is closer structurally to early Post-Classical Greek than the latter is to Classical Greek. Thus some works dealing with Post-Classical Greek, especially as it illuminates the nature of the modern language — regional dialect variants included — have been selected for this bibliography, as have a few general overviews of the history of Greek from Classical or even pre-Classical times to the present. -

Notes from the Oriental Seminary

JOHNS HOPKiNS UNIVERSITY CIRCULARS Published with the approbation of the Board of Trustees VOL. XXIJ.—No. 163.1 BALTIMORE, JUNE, 1903. [PRICE, 10 CENTS. ENTERED AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER AT THE BALTIMORE, MARYLAND, POSTOFFICE. NOTES FROM THE ORIENTAL SEMINARY. EDITED BY PROFESSOR PAUL HAUPT, LL. DA~ More than twenty years ago Delitzsch delivered a lecture on BIBLE AND BABEL. the location of Paradise,0 which contained, perhaps, just as By PAUL HAUPT. much that was new and revolutionary from the traditional point of view as his recent lectures on Babel and Bible, but—the [Abstract of a paper read at the meeting of the American Oriental Society, Baltimore, April 17, 1903.] German Emperor was not present and did not command a repetition of the lecture at the Imperial Palace; nor did he deem The pessimistic philosopher who wrote the original portions of it necessary to define his faith in an open letter. Delitzsch’s the Book of Ecelesiastes, probably not long before the time of 1 says, The race does not belong to the swift, nor Ex Oriente Lux, written about five years ago for the German our Savior, the battle to the strong: everything depends on time and chance. Orient Society, did not stir up a sensation, although he pointed (EccI. 9, 11). If my distinguished friend, Professor Friedrich out there just as plainly I that the Old Testament contained a Delitzsch, of Berlin, had not delivered (Jan. 13, 1902) his lecture great deal derived from Babylonian sources.—Everything depends on Babel and Bible2 in the presence of the German Emperor, on time and chance. -

The Alphabets of the Bible: Greek

130 The Testimony, April 2004 lessons can be based on things relating to the Likewise there are great rocks along the way physical world. where we may find shade from the heat of the Our life in this age is a journey through a sun, and springs of water welling up to the sur- spiritual wilderness while we set our vision face where we may rest awhile to be refreshed. ahead, looking for “the city which has founda- So it is on the spiritual level that we can benefit tions, whose builder and maker is God” (Heb. from attending Bible classes and other ecclesial 11:10, NKJV; cf. 13:14). meetings, as well as being a help to others who The scorching rays of the sun that we experi- are travelling with us. ence in this spiritual desert are the tribulations However, our journey through the wilderness and difficulties that test our faith and help us to does have its perils, particularly if we do not develop characters pleasing to our heavenly Fa- keep up with our brethren and sisters but allow ther (Mt. 13:5,6,20,21; Lk. 8:13). If we fail to tap ourselves to become spiritual stragglers. The into the water of life that is provided we will be spiritual counterpart of Amalek is the power of spiritually unfruitful. That water is available sin that lies in wait to trap the unwary traveller daily in the form of the Word of God, and we and at the same time seeks to steal away the neglect it at our peril. -

Free Sampler

ISSN: 2059-4674 Journal of Greek Archaeology Volume 5 2020 FREE SAMPLER Archaeopress JOURNAL OF GREEK ARCHAEOLOGY An international journal publishing contributions in English and specialising in synthetic articles and in long reviews. Work from Greek scholars is particularly welcome. The scope of the journal is Greek archaeology both in the Aegean and throughout the wider Greek- inhabited world, from earliest Prehistory to the Modern Era. Thus included are contributions not just from traditional periods such as Greek Prehistory and the Classical Greek to Hellenistic eras, but also from Roman through Byzantine, Crusader and Ottoman Greece and into the Early Modern period. Contributions covering the Archaeology of the Greeks overseas beyond the Aegean are welcome, likewise from Prehistory into the Modern World. Greek Archaeology, for the purposes of the JGA, includes the Archaeology of the Hellenistic World, Roman Greece, Byzantine Archaeology, Frankish and Ottoman Archaeology, and the Postmedieval Archaeology of Greece and of the Greek Diaspora. The journal appears annually and incorporates original articles, research reviews and book reviews. Articles are intended to be of interest to a broad cross-section of archaeologists, art historians and historians concerned with Greece and the development of Greek societies, and can be up to 10,000 words long. They are syntheses with bibliography of recent work on a particular aspect of Greek archaeology; or summaries with bibliography of recent work in a particular geographical region; or articles which cross national or other boundaries in their subject matter; or articles which are likely to be of interest to a broad range of archaeologists and other researchers for their theoretical or methodological aspects. -

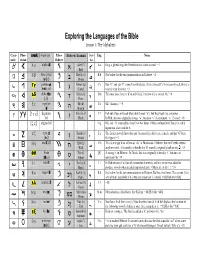

Exploring the Languages of the Bible Lesson 1: the Alphabets

Exploring the Languages of the Bible Lesson 1: The Alphabets Cana- Phoe- Greek []=Erasmian Paleo- Hebrew/Aramaic Syr- Eng. Notes anite nician Hebrew iac A Α α alpha (ăăăă) Alef ( ) A a Orig. a glottal stop, the Greeks turned it into a vowel. =1 א ˆ Bull א B Β β Beta [vīta] Bet (b, v) B b See below for the two pronunciations in Hebrew. =2 ב ˈ House ב ([vvvv [b) Γ γΓ γ gamma (gggghhhh, Gimel (g) C c Our ‘G’ and our ‘C’ come from this letter (G is a voiced C). In modern Greek, this is a ג Camel ˉ voiced velar fricative. =3 ג ([C yyy,y ngngng [g, ng D ∆ δ∆ δ delta (thththth is Dalet (d) D d This may have been a ‘d’ in old Greek, but now it is a voiced ‘th.’ =4 ד ˌ Door ד ([d] E Ε ε e-psilon He (h) E e Gk: ‘skinny e.’ =5 ה ˍ Breath ה (ĕĕĕĕ) .FU [̥ ] digamma Vav (w, v) F f Fell out of use in Greek (they didn’t need ‘w’), but they kept it as a number ו Hook ˎ In Heb, this was originally always ‘w’, but now ‘v’ if consonant, ‘w’ if vowel. =6 ו (w) [ ] stigma (st) G g OK, our ‘G’ may really come from this letter. Often confused with Fau, it is really sigma-tau, also used for 6. .z Ζ ζ zeta (zzzz Zayin (z) Z z The Latins moved this to the end, because they didn’t use it much, and put ‘G’ here ז Sword ˏ Go figure! =7 ז ([dz] H Η η eta (īīīī [ā]) Ḫet ( ḫ) H h This is stronger than a German ‘ch’ in Phoenician / Hebrew, but the Greeks needed ח Wall another vowel. -

The Western Question in Greece and Turkey

THE WESTERN QUESTION IN GREECE AND TURKEY A STUDY IN THE CONTACT OF CIVILISATIONS BY ARNOLD J. TOYNBEE ‘For we are also His offspring’ CONSTABLE AND COMPANY LTD LONDON · BOMBAY · SYDNEY 1922 TO THE PRESIDENT AND FACULTY OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE FOR GIRLS AT CONSTANTINOPLE THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR AND HIS WIFE IN GRATITUDE FOR THEIR HOSPITALITY AND IN ADMIRATION OF THEIR NEUTRAL-MINDEDNESS IN CIRCUMSTANCES IN WHICH NEUTRALITY IS ‘HARD AND RARE’ PREFACE THIS book is an attempt to place certain recent events in the Near and Middle East in their historical setting, and to illustrate from them several new features of more enduring importance than the events themselves. It is not a discussion of what the peace-settlement in the East ought to be, for the possibility of imposing a cut-and-dried scheme, if it ever really existed, was destroyed by the landing of the Greek troops at Smyrna in May 1919. At any rate, from that moment the situation resolved itself into a conflict of forces beyond control; the Treaty of Sèvres was still-born; and subsequent conferences and agreements, however imposing, have had and are likely to have no more than a partial and temporary effect. On the other hand, there have been real changes in the attitude of the Western public towards their Governments’ Eastern policies, which have produced corresponding changes in those policies themselves; and the Greeks and Turks have appeared in unfamiliar roles. The Greeks have shown the same unfitness as the Turks for governing a mixed population. The Turks, in their turn, have become exponents of the political nationalism of the West.