Free Sampler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REMOTE SENSING a Bibliography of Cultural Resource Studies

REMOTE SENSING A Bibliography of Cultural Resource Studies Supplement No. 0 REMOTE SENSING Aerial Anthropological Perspectives: A Bibliography of Remote Sensing in Cultural Resource Studies Thomas R. Lyons Robert K. Hitchcock Wirth H. Wills Supplement No. 3 to Remote Sensing: A Handbook for Archeologists and Cultural Resource Managers Series Editor: Thomas R. Lyons Cultural Resources Management National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 1980 Acknowledgments This bibliography on remote sensing in cultural Numerous individuals have aided us. We es resource studies has been compiled over a period pecially wish to acknowledge the aid of Rosemary of about five years of research at the Remote Sen Ames, Marita Brooks, Galen Brown, Dwight Dra- sing Division, Southwest Cultural Resources Cen ger, James Ebert, George Gumerman, James ter, National Park Service. We have been aided Judge, Stephanie Klausner, Robert Lister, Joan by numerous government agencies in the course Mathien, Stanley Morain and Gretchen Obenauf. of this work, including the Department of the In Douglas Scovill, Chief Anthropologist of the Na terior, National Park Service, the U.S. Geological tional Park Service has also encouraged and sup Survey EROS Program, and the National Aero ported us in the pursuit of new research directions. nautics and Space Administration (NASA). Fi Christina Allen aided immeasurably in the com nancial support has been provided by these pilation of this bibliography, not only in procuring agencies as well as by the National Geographic references (especially those dealing with under Society (Grant No. 1177). The Department of An water remote sensing), but also in proofreading the thropology, University of New Mexico, and the entire manuscript. -

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The eighth-century revolution Version 1.0 December 2005 Ian Morris Stanford University Abstract: Through most of the 20th century classicists saw the 8th century BC as a period of major changes, which they characterized as “revolutionary,” but in the 1990s critics proposed more gradualist interpretations. In this paper I argue that while 30 years of fieldwork and new analyses inevitably require us to modify the framework established by Snodgrass in the 1970s (a profound social and economic depression in the Aegean c. 1100-800 BC; major population growth in the 8th century; social and cultural transformations that established the parameters of classical society), it nevertheless remains the most convincing interpretation of the evidence, and that the idea of an 8th-century revolution remains useful © Ian Morris. [email protected] 1 THE EIGHTH-CENTURY REVOLUTION Ian Morris Introduction In the eighth century BC the communities of central Aegean Greece (see figure 1) and their colonies overseas laid the foundations of the economic, social, and cultural framework that constrained and enabled Greek achievements for the next five hundred years. Rapid population growth promoted warfare, trade, and political centralization all around the Mediterranean. In most regions, the outcome was a concentration of power in the hands of kings, but Aegean Greeks created a new form of identity, the equal male citizen, living freely within a small polis. This vision of the good society was intensely contested throughout the late eighth century, but by the end of the archaic period it had defeated all rival models in the central Aegean, and was spreading through other Greek communities. -

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia (8th – 6th centuries BCE) An honors thesis for the Department of Classics Olivia E. Hayden Tufts University, 2013 Abstract: Although ancient Greeks were traversing the western Mediterranean as early as the Mycenaean Period, the end of the “Dark Age” saw a surge of Greek colonial activity throughout the Mediterranean. Contemporary cities of the Greek homeland were in the process of growing from small, irregularly planned settlements into organized urban spaces. By contrast, the colonies founded overseas in the 8th and 6th centuries BCE lacked any pre-existing structures or spatial organization, allowing the inhabitants to closely approximate their conceptual ideals. For this reason the Greek colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia, known for their extensive use of gridded urban planning, exemplified the overarching trajectory of urban planning in this period. Over the course of the 8th to 6th centuries BCE the Greek cities in Sicily and Magna Graecia developed many common features, including the zoning of domestic, religious, and political space and the implementation of a gridded street plan in the domestic sector. Each city, however, had its own peculiarities and experimental design elements. I will argue that the interplay between standardization and idiosyncrasy in each city developed as a result of vying for recognition within this tight-knit network of affluent Sicilian and South Italian cities. This competition both stimulated the widespread adoption of popular ideas and encouraged the continuous initiation of new trends. ii Table of Contents: Abstract. …………………….………………………………………………………………….... ii Table of Contents …………………………………….………………………………….…….... iii 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………..……….. 1 2. -

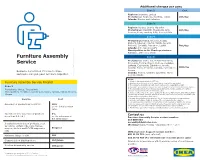

Assembly Leaflet AES ACS

Additional charges per zone Υπηρεσία Zone 2 Cost Regions: Ioannina, Larissa συναρμολόγησης επίπλων Prefectures: Magnesia, Karditsa, Trikala 20€/day Islands: Rhodes and Salamina Zone 3 Regions: Achaea, Chania, Heraklion Prefectures: Chalkidiki, Thesprotia, Arta, 40€/day Preveza, Pieria, Imathia, Pella, Serres, Kilkis Zone 4 Prefectures: Drama, Grevena, Kozani, Kastoria, Rhodope, Kavala, Xanthi, Boeotia, Phthiotis, Corinthia, Rethymno, Lasithi 70€/day © Islands: Argo-Saronic Gulf's Inter IKEA Systems B.V. 2018 B.V. Inter IKEA Systems Municipalities in the Chania prefecture: Kantanos, Selino and Sfakia Furniture Assembly Zone 5 Prefectures: Corfu, Ilia, Aetolia-Acarnania, Service Evrytania, Florina, Phocis, Euboea, Cyclades, Lefkada, Cephalonia, Zakynthos, Argolis, Arcadia, Evros, Messinia, Laconia, Dodecanese, 100€/day Because sometimes it’s nice to have Lesbos Islands: Thasos, Cythera, Sporades, North someone else put your furniture together. Aegean islands Notes: 1. All above listed prices include VAT 24%. Furniture Assembly Service Pricelist 2. Furniture must be located to the space where they will be assembled. 3. The charge for an additional visit, due to customer’s responsibility, is 25€. Zone 1 4. Consumer is not obliged to pay if the notice of payment is not received (receipt-invoice). Prefectures: Attica, Thessaloniki 5. The assembly charge for products purchased from the As-Is Department or with a discount is calculated based on their initial value. Municipalities: Heraklion, Ioannina, Komotini, Larissa, Patras, Rhodes, 6. Disassembly service in the store, applies for the stores IKEA Airport, IKEA Kifissos, IKEA Chania Thessaloniki and IKEA Ioannina. Maximum waiting time is 2 hours. Service is available until 2 hours before closing time of the store. -

SALES MANUAL 2021 2 2 Dear Colleagues and Friends

SALES MANUAL 2021 2 2 Dear Colleagues and Friends, I welcome you to a year which is fundamentally different to any for private events and masterclasses with Michelin-starred chefs. other we have previously encountered and collaborated on. The The Clumsies, the third best bar in the world, inspired with their landscape of our profession in tourism has changed drastically energy and an unparalleled cocktail experience at the Cove. BXR through the course of the Covid-19 pandemic and continues to London, gave an edge to our fitness programmes, with retreats evolve. Nevertheless, we successfully weathered summer 2020 as including strengthening sessions, boxing, cardiovascular workouts one of a finite number of places in the world to welcome guests in and yoga at a great level of personal training. Beyond the retreats, a globally unsettled environment. I personally see this achievement BXR visiting trainers provided top-level fitness throughout the as a result of constructive brainstorming, singular preparation and season. Furthermore, our collaborations with Land Rover and the ability to skillfully embrace challenges. The team’s unwavering Technohull, have given our guests the opportunity to explore the energy and ambition to establish the Cove as a safe haven during a stunning mountains and seascape of Crete with unparalleled privacy pandemic in the modern era became a reality. and style. Moving forward we look to our assets and embellish these by dynamically developing our offering of a magical holiday in a truly However, the most important element of our accomplishments and safe place. First and foremost, the adherence and utter belief in future endeavours is found on the last page of the manual. -

Early Mycenaean Arkadia: Space and Place(S) of an Inland and Mountainous Region

Early Mycenaean Arkadia: Space and Place(s) of an Inland and Mountainous Region Eleni Salavoura1 Abstract: The concept of space is an abstract and sometimes a conventional term, but places – where people dwell, (inter)act and gain experiences – contribute decisively to the formation of the main characteristics and the identity of its residents. Arkadia, in the heart of the Peloponnese, is a landlocked country with small valleys and basins surrounded by high mountains, which, according to the ancient literature, offered to its inhabitants a hard and laborious life. Its rough terrain made Arkadia always a less attractive area for archaeological investigation. However, due to its position in the centre of the Peloponnese, Arkadia is an inevitable passage for anyone moving along or across the peninsula. The long life of small and medium-sized agrarian communities undoubtedly owes more to their foundation at crossroads connecting the inland with the Peloponnesian coast, than to their potential for economic growth based on the resources of the land. However, sites such as Analipsis, on its east-southeastern borders, the cemetery at Palaiokastro and the ash altar on Mount Lykaion, both in the southwest part of Arkadia, indicate that the area had a Bronze Age past, and raise many new questions. In this paper, I discuss the role of Arkadia in early Mycenaean times based on settlement patterns and excavation data, and I investigate the relation of these inland communities with high-ranking central places. In other words, this is an attempt to set place(s) into space, supporting the idea that the central region of the Peloponnese was a separated, but not isolated part of it, comprising regions that are also diversified among themselves. -

ANASTASIOS GEORGOTAS “Archaeological Tourism in Greece

UNIVERSITY OF THE PELOPONNESE ANASTASIOS GEORGOTAS (R.N. 1012201502004) DIPLOMA THESIS: “Archaeological tourism in Greece: an analysis of quantitative data, determining factors and prospects” SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: - Assoc. Prof. Nikos Zacharias - Dr. Aphrodite Kamara EXAMINATION COMMITTEE: - Assoc. Prof. Nikolaos Zacharias - Dr. Aphrodite Kamara - Dr. Nikolaos Platis ΚΑΛΑΜΑΤΑ, MARCH 2017 Abstract . For many decades now, Greece has invested a lot in tourism which can undoubtedly be considered the country’s most valuable asset and “heavy industry”. The country is gifted with a rich and diverse history, represented by a variety of cultural heritage sites which create an ideal setting for this particular type of tourism. Moreover, the variations in Greece’s landscape, cultural tradition and agricultural activity favor the development and promotion of most types of alternative types of tourism, such as agro-tourism, religious, sports and medicinal tourism. However, according to quantitative data from the Hellenic Statistical Authority, despite the large number of visitors recorded in state-run cultural heritage sites every year, the distribution pattern of visitors presents large variations per prefecture. A careful examination of this data shows that tourist flows tend to concentrate in certain prefectures, while others enjoy little to no visitor preference. The main factors behind this phenomenon include the number and importance of cultural heritage sites and the state of local and national infrastructure, which determines the accessibility of sites. An effective analysis of these deficiencies is vital in order to determine solutions in order to encourage the flow of visitors to the more “neglected” areas. The present thesis attempts an in-depth analysis of cultural tourism in Greece and the factors affecting it. -

Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1989 Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848 Leopold G. Glueckert Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Glueckert, Leopold G., "Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848" (1989). Dissertations. 2639. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2639 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert BETWEEN TWO AMNESTIES: FORMER POLITICAL PRISONERS AND EXILES IN THE ROMAN REVOLUTION OF 1848 by Leopold G. Glueckert, O.Carm. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert 1989 © All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with any paper which has been under way for so long, many people have shared in this work and deserve thanks. Above all, I would like to thank my director, Dr. Anthony Cardoza, and the members of my committee, Dr. Walter Gray and Fr. Richard Costigan. Their patience and encourage ment have been every bit as important to me as their good advice and professionalism. -

Science in Archaeology: a Review Author(S): Patrick E

Science in Archaeology: A Review Author(s): Patrick E. McGovern, Thomas L. Sever, J. Wilson Myers, Eleanor Emlen Myers, Bruce Bevan, Naomi F. Miller, S. Bottema, Hitomi Hongo, Richard H. Meadow, Peter Ian Kuniholm, S. G. E. Bowman, M. N. Leese, R. E. M. Hedges, Frederick R. Matson, Ian C. Freestone, Sarah J. Vaughan, Julian Henderson, Pamela B. Vandiver, Charles S. Tumosa, Curt W. Beck, Patricia Smith, A. M. Child, A. M. Pollard, Ingolf Thuesen, Catherine Sease Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 99, No. 1 (Jan., 1995), pp. 79-142 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/506880 Accessed: 16/07/2009 14:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aia. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

December 2010

International I F L A Preservation PP AA CC o A Newsletter of the IFLA Core Activity N . 52 News on Preservation and Conservation December 2010 Tourism and Preservation: Some Challenges INTERNATIONAL PRESERVATION Tourism and Preservation: No 52 NEWS December 2010 Some Challenges ISSN 0890 - 4960 International Preservation News is a publication of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Core 6 Activity on Preservation and Conservation (PAC) The Economy of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Conservation that reports on the preservation Valéry Patin activities and events that support efforts to preserve materials in the world’s libraries and archives. 12 IFLA-PAC Bibliothèque nationale de France Risks Generated by Tourism in an Environment Quai François-Mauriac with Cultural Heritage Assets 75706 Paris cedex 13 France Miloš Drdácký and Tomáš Drdácký Director: Christiane Baryla 18 Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 70 Fax: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 80 Cultural Heritage and Tourism: E-mail: [email protected] A Complex Management Combination Editor / Translator Flore Izart The Example of Mauritania Tel: ++ 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 71 Jean-Marie Arnoult E-mail: fl [email protected] Spanish Translator: Solange Hernandez Layout and printing: STIPA, Montreuil 24 PAC Newsletter is published free of charge three times a year. Orders, address changes and all The Challenge of Exhibiting Dead Sea Scrolls: other inquiries should be sent to the Regional Story of the BnF Exhibition on Qumrân Manuscripts Centre that covers your area. 3 See