Copyright by Miriam Rafia Murtuza 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Indian Englishman

AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN MEMOIRS OF JACK GIBSON IN INDIA 1937–1969 Edited by Brij Sharma Copyright © 2008 Jack Gibson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means—whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law. ISBN: 978-1-4357-3461-6 Book available at http://www.lulu.com/content/2872821 CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 To The Doon School 5 Bandarpunch-Gangotri-Badrinath 17 Gulmarg to the Kumbh Mela 39 Kulu and Lahul 49 Kathiawar and the South 65 War in Europe 81 Swat-Chitral-Gilgit 93 Wartime in India 101 Joining the R.I.N.V.R. 113 Afloat and Ashore 121 Kitchener College 133 Back to the Doon School 143 Nineteen-Fortyseven 153 Trekking 163 From School to Services Academy 175 Early Days at Clement Town 187 My Last Year at the J.S.W. 205 Back Again to the Doon School 223 Attempt on ‘Black Peak’ 239 vi An Indian Englishman To Mayo College 251 A Headmaster’s Year 265 Growth of Mayo College 273 The Baspa Valley 289 A Half-Century 299 A Crowded Programme 309 Chini 325 East and West 339 The Year of the Dragon 357 I Buy a Farm-House 367 Uncertainties 377 My Last Year at Mayo College 385 Appendix 409 PREFACE ohn Travers Mends (Jack) Gibson was born on March 3, 1908 and J died on October 23, 1994. -

Tragic Orphans: Indians in Malaysia

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj, Tunku. Looking Back: The Historic Years of Malaya and Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Pustaka Antara, 1977. ———. Viewpoints. Kuala Lumpur: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia), 1978. Abdul Rashid Moten. “Modernization and the Process of Globalization: The Muslim Experience and Responses”. In Islam in Southeast Asia: Political, Social and Strategic Challenges for the 21st Century, edited by K.S. Nathan and Mohammad Hashim Kamali. Singapore: Institute for Southeast Asian Studies, 2005. Abraham, Collin. “Manipulation and Management of Racial and Ethnic Groups in Colonial Malaysia: A Case Study of Ideological Domination and Control”. In Ethnicity and Ethnic Relations in Malaysia, edited by Raymond L.M. Lee. Illinois: Northern Illinois University, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, 1986. ———. The Naked Social Order: The Roots of Racial Polarisation in Malaysia. Subang Jaya: Pelanduk, 2004 (1997). ———. “The Finest Hour”: The Malaysian-MCP Peace Accord in Perspective. Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, 2006. Abu Talib Ahmad. “The Malay Community and Memory of the Japanese Occupation”. In War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore, edited by Patricia Lim Pui Huen and Diana Wong. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2000. ———. The Malay Muslims, Islam and the Rising Sun: 1941–1945. Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS, 2003. Ackerman, Susan E. and Raymond L.M. Lee. Heaven in Transition: Innovation and Ethnic Identity in Malaysia. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1988. Aeria, Andrew. “Skewed Economic Development and Inequality: The New Economic Policy in Sarawak”. In The New Economic Policy in Malaysia: Affirmative Action, Ethnic Inequalities and Social Justice, edited by Edmund Terence Gomez and Johan Saravanamuttu. -

An Examination of Regional Views on South Asian Co-Operation with Special Reference to Development and Security Perspectives in India and Shri Lanka

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Northi Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Chapter-Ii Historical Background of Public Schools

C H APTER -II HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF PUBLIC SCHOOLS 2.0 INTRODUCTORY REMARKS The purpose of this chapter is to give an account of historical back ground of Public Schools, both in England and in India. It is essential to know the origin and development of Public Schools in England, as Public Schools in India had been transplanted from England. 2.1 ORIGIN OF THE TERM PUBLIC SCHOOL The term 'Public School' finds its roots in ancient times. In ancient time kings and bishops used to run the schools for the poor. No fee was charged. All used to live together. It was a union of 'classes'. The expenses were met by public exchequer. Thus the name was given to these schools as Public Schools. 2.2 ESTABLISHMENT OF FIRST PUBLIC SCHOOLS William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester established 'Saint Marie College' at Winchester in 1382. This foundation made a crucial departure from previous practice and thus, has a great historical importance. All the previous schools had been ancillary to other establishments; they Kod been established as parts of cathedrals, collegiate churches, monasteries, chantries, hospitals or university colleges. The significance of this college is its independent nature. 17 Its historian, A.F. Leach says "Thus for the first time a school was established as a sovereign and independent corporation, existing by and for itself, self-centered and self-governed."^ The foundation of Winchester College is considered to be the origin of the English Public School because of three conditions: 1. Pupils were to be accepted from anywhere in England (though certain countries had priority). -

The Malay Language 'Pantun' of Melaka Chetti Indians in Malaysia

International Journal of Comparative Literature & Translation Studies ISSN: 2202-9451 www.ijclts.aiac.org.au The Malay Language ‘Pantun’ of Melaka Chetti Indians in Malaysia: Malay Worldview, Lived Experiences and Hybrid Identity Airil Haimi Mohd Adnan*, Indrani Arunasalam Sathasivam Pillay Academy of Language Studies,, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Perak Branch, Seri Iskandar Campus, 32610 State of Perak, Malaysia Corresponding Author: Airil Haimi Mohd Adnan, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history The Melaka Chetti Indians are a small community of ‘peranakan’ (Malay meaning ‘locally born’) Received: January 26, 2020 people in Malaysia. The Melaka Chettis are descendants of traders from the Indian subcontinent Accepted: March 21, 2020 who married local women, mostly during the time of the Melaka Malay Empire from the 1400s Published: April 30, 2020 to 1500s. The Melaka Chettis adopted the local lingua franca ‘bahasa Melayu’ or Malay as Volume: 8 Issue: 2 their first language together with the ‘adat’ (Malay meaning ‘customs’) of the Malay people, their traditional mannerisms and also their literary prowess. Not only did the Melaka Chettis successfully adopted the literary traditions of the Malay people, they also adapted these arts Conflicts of interest: None forms to become part of their own unique hybrid identities based on their worldviews and lived Funding: This empirical research proj- experiences within the Malay Peninsula or more famously known as the Golden Chersonese / ect was made possible by the -

Magazine 7 Mar 2016

The Development & Alumni Relations Office Newsletter MAY 2016 Dear fellow Doscos, teachers are actively engaged in we were all beneficiaries of a unique campus life. educational experience at Doon and we I feel honoured and privileged to have Ÿ Starting new programs like Summer wanted the legacy to continue for served as a Governor of The Doon at Doon, and the teacher training future generations. I have four boys and School. During this time I have also with the Institute of Education none of them did or will attend Doon, carried the responsibility of leading (IOE). so the legacy is not a personal one. the newly founded Development Ÿ Upgrading the quality of college Committee, which plays the role of counselling and placements. Like many of you I had the good raising funds to support the enticing Ÿ And last, but perhaps most fortune of being involved in some new initiatives that Dr Peter importantly, upgrading the physical world class educational institutions as a McLaughlin, Headmaster, and facilities in the houses, developing a student, as a parent, and as a trustee. Mr Gautam Thapar, Chairman of the long term estate plan, and I don't believe I am exaggerating when BOG, have started. completing the Art School. I say that Doon stands up there with the best of them. Arguably, if one I’m pleased to report that, due to the No doubt there are several other key judges a school by whether it inspires support of Old boys and friends of the needs, still unmet, that are worthy of its students to make a difference in the Doon family, we have raised Rs 36.18 your support. -

Development Plan

The Doon School Development Plan Maintaining our pre-eminence May 2012 The Doon School The Mall Dehradun 248001 Uttaranchal India Tel: +91-135-2526-400 Fax: +91-135-275-7275 The Doon School Development Plan: Maintaining our pre-eminence, May 2012 Copyright © 2012 by The Doon School This report is being communicated to the recipient on a confidential basis and does not carry any right of publication or disclosure to any third party. By accepting delivery of this report, the recipient undertakes not to reproduce or distribute this report in whole or in part, nor to disclose any of its contents, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the express prior written consent from The Doon School. Cover Photo: © Amit Pasricha The Doon School Development Plan Maintaining our pre-eminence May 2012 From its very inception and opening in 1935, The Doon School was clearly an Indian school, developing “… boys to serve a free and democratic India”, as articulated by Arthur Foot, the School’s first headmaster. Each aspect of the School was designed to prepare leaders who would build and serve a great nation. The Doon School Development Plan 2 Maintaining our pre-eminence: The Doon School Development Plan From its very inception and opening in 1935, The Doon School was clearly an Indian school, developing “…boys to serve a free and democratic India,” as articulated by Arthur Foot, the School’s first headmaster. Each aspect of the School was designed to prepare leaders who would build and serve a great nation. Boys from every background, caste, race, creed, and religion proudly sang the national anthem before it was adopted by a free India; boys and teachers were taught to value service before self; and secularism, discipline, and equality characterised the School’s playgrounds, houses, and classrooms long before these values reached other schools or the nation. -

Wolverhampton City Council OPEN INFORMATION ITEM

Agenda Item No: 14 Wolverhampton City Council OPEN INFORMATION ITEM Committee / Panel PLANNING COMMITTEE Date 31-OCT-2006 Originating Service Group(s) REGENERATION AND ENVIRONMENT Contact Officer(s)/ STEPHEN ALEXANDER (Head of Development Control) Telephone Number(s) (01902) 555610 Title/Subject Matter APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER OFFICER DELEGATION, WITHDRAWN, ETC. The attached Schedule comprises planning and other application that have been determined by authorised officers under delegated powers given by Committee, those applications that have been determined following previous resolutions of Planning Committee, or have been withdrawn by the applicant, or determined in other ways, as details. Each application is accompanied by the name of the planning officer dealing with it in case you need to contact them. The Case Officers and their telephone numbers are Wolverhampton (01902): Major applications Minor/Other Applications Stephen Alexander 555610 (Head of DC) Alan Murphy 555623 (Acting Assistant Head of DC) Ian Holiday 555630 (Senior Planning Officer) Alan Gough 555648 (Senior Planning Officer - Commercial) Mizzy Marshall 551133 Martyn Gregory 551125 (Planning Officer) (Senior Planning Officer - Residential) Ken Harrop (Planning Officer) 555649 Ragbir Sahota (Planning Officer) 555616 Mark Elliot (Planning Officer) 555632 Jenny Davies (Planning Officer) 555608 Tracey Homfray (Planning Officer) 555641 Mindy Cheema (Planning Officer) 551360 Rob Hussey (Planning Officer) 551130 Nussarat Malik (Planning Officer) 551132 Philip Walker (Planning -

The Doon School Weekly Saturday, August 16|Issue No

ESTABLıSHED ın 1936 The Doon School Weekly Saturday, August 16|Issue No. 2379 Regulars Interview Week Gone By Poetry 2 3 3 4 DISCOVERY WEEK AT CERN Preetam Mohan reports on the visit to CERN which took place during the holidays On the 15th of June, a group of nine boys escorted by Dr Ashish Dean left for Geneva, Switzerland to experience life in one of the finest institutions in the world in its field - European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN). It was a most exciting prospect as School had organized a program of such magnitude for the first time, and it was supported by the fact that all of us had an interest in the field of work explored at CERN. The five-day internship program kicked off at 0800 hours on the 16th of June, with us meeting some of the topmost authorities at CERN. The highlight was meeting the Director General, Dr Rolf Dieter Heuer himself. The ‘showcases of CERN’, the Microcosm and the Globe provided us a preview of what we might be staring at for the next five days. It, befittingly, related to the modern day applications and we were drawn into the origin and the thoughts that revolved around such discoveries. The day was organized in a way to expose us to what CERN’s aim is: exploring Fundamental questions such as ‘where do we come from?’ and ‘what are we made of?’ These gave the internship the intellectual gravitas that it deserved. After visiting the computing centre we learnt that India has two centers on the CERN radar and we were happy to know that so many countries had pooled in resources to further the cause of science through CERN. -

Sir Henry Newbolt 1862-1938 ©Wiltshire OPC Project/Linda

Sir Henry Newbolt 1862-1938 Sir Henry Newbolt was born In Bilston, Staffordshire on 6th June 1862, the son of Rev. Henry Francis & Emily Newbolt. He was just four years old when his father died. At the age of 10 Henry was sent to a boarding school in Lincolnshire, from where he won a scholarship to Clifton College. He later went to Corpus Christi College, Oxford and began a legal career, practising at the Chancery Bar from 1887 to 1889. He was a lawyer, novelist, and playwright and wrote many poems. His most famous work was Vitai Lampada. He was employed by the Government during WWI to serve on the War Propaganda Bureau to encourage the public to support the war. He subsequently became Controller of Telecommunications at the Foreign Office. His poems about the war include "The War Films", printed on the leader page of The Times on 14 October 1916, which seeks to temper the shock effect on cinema audiences of footage of the Battle of the Somme. He also wrote a paper in 1921 for the government, which established the foundation for modern English studies and professionalised the forms of teaching English literature. Sir Henry Newbolt lived for many years at Netherhampton House with his wife Margaret. His granddaughter Jill Furse married Rex Whistler’s brother Laurence. He was knighted in 1915. Newbolt died at his home in Campden Hill, Kensington, London, on 19 April 1938, aged 75. A blue plaque there commemorates his residency. He is buried in the churchyard of St Mary's church on an island in the lake on the Orchardleigh Estate of the Duckworth family in Somerset. -

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

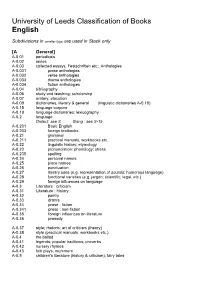

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies -

LUCRETIUS -- the Nature of Things Trans

REDUX EDITION* LUCRETIUS The Nature of Things Translated and with Notes by A. E. STALLINGS Introduction by RICHARD JENKYNS PENGUIN BOOKS * See the release notes for details LINE NUMBERING: The lines of the poem are numbered by tens, with the exception of line II.1021 which was marked instead of line II.1020 (unclear whether intended or by error) and the lines I.690 and I.1100 which were skipped altogether. The line numbering follows the 1947 Latin edition of Cyril Bailey and not this English translation (confusing but helpful when referencing other translations/commentaries). As stated in the "Note on the Text and Translation", the author joined together and restructured lines for the needs of this translation. Consequently, the number of actual lines between adjacent multiples of ten (or "decades") are often a couple of lines less or more than the ten of the referenced Latin edition. As far as line references in the notes are concerned, they are with maybe a few exceptions in alignment with the numbering of their closest multiple of ten. MISSING SECTIONS: As mentioned in the "Note on the Text and Translation", missing sections (or "lacunae") of which there are a few, are denoted with three dots and/or an explanation enclosed in square brackets. LINE STRUCTURE: The structure of the translation is rhymed couplets, meaning that you'll mostly (though not exclusively) have consecutive pairs of rhymed lines throughout the entire poem. The poem itself is broken up with occasional standard line breaks, as one would expect, but also with a more peculiar feature that might best be described as indented line breaks.