In the Newbolt Report (1921) and in the Bullock Report (1974)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolverhampton City Council OPEN INFORMATION ITEM

Agenda Item No: 14 Wolverhampton City Council OPEN INFORMATION ITEM Committee / Panel PLANNING COMMITTEE Date 31-OCT-2006 Originating Service Group(s) REGENERATION AND ENVIRONMENT Contact Officer(s)/ STEPHEN ALEXANDER (Head of Development Control) Telephone Number(s) (01902) 555610 Title/Subject Matter APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER OFFICER DELEGATION, WITHDRAWN, ETC. The attached Schedule comprises planning and other application that have been determined by authorised officers under delegated powers given by Committee, those applications that have been determined following previous resolutions of Planning Committee, or have been withdrawn by the applicant, or determined in other ways, as details. Each application is accompanied by the name of the planning officer dealing with it in case you need to contact them. The Case Officers and their telephone numbers are Wolverhampton (01902): Major applications Minor/Other Applications Stephen Alexander 555610 (Head of DC) Alan Murphy 555623 (Acting Assistant Head of DC) Ian Holiday 555630 (Senior Planning Officer) Alan Gough 555648 (Senior Planning Officer - Commercial) Mizzy Marshall 551133 Martyn Gregory 551125 (Planning Officer) (Senior Planning Officer - Residential) Ken Harrop (Planning Officer) 555649 Ragbir Sahota (Planning Officer) 555616 Mark Elliot (Planning Officer) 555632 Jenny Davies (Planning Officer) 555608 Tracey Homfray (Planning Officer) 555641 Mindy Cheema (Planning Officer) 551360 Rob Hussey (Planning Officer) 551130 Nussarat Malik (Planning Officer) 551132 Philip Walker (Planning -

Sir Henry Newbolt 1862-1938 ©Wiltshire OPC Project/Linda

Sir Henry Newbolt 1862-1938 Sir Henry Newbolt was born In Bilston, Staffordshire on 6th June 1862, the son of Rev. Henry Francis & Emily Newbolt. He was just four years old when his father died. At the age of 10 Henry was sent to a boarding school in Lincolnshire, from where he won a scholarship to Clifton College. He later went to Corpus Christi College, Oxford and began a legal career, practising at the Chancery Bar from 1887 to 1889. He was a lawyer, novelist, and playwright and wrote many poems. His most famous work was Vitai Lampada. He was employed by the Government during WWI to serve on the War Propaganda Bureau to encourage the public to support the war. He subsequently became Controller of Telecommunications at the Foreign Office. His poems about the war include "The War Films", printed on the leader page of The Times on 14 October 1916, which seeks to temper the shock effect on cinema audiences of footage of the Battle of the Somme. He also wrote a paper in 1921 for the government, which established the foundation for modern English studies and professionalised the forms of teaching English literature. Sir Henry Newbolt lived for many years at Netherhampton House with his wife Margaret. His granddaughter Jill Furse married Rex Whistler’s brother Laurence. He was knighted in 1915. Newbolt died at his home in Campden Hill, Kensington, London, on 19 April 1938, aged 75. A blue plaque there commemorates his residency. He is buried in the churchyard of St Mary's church on an island in the lake on the Orchardleigh Estate of the Duckworth family in Somerset. -

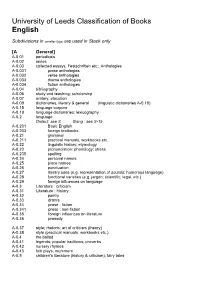

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies -

LUCRETIUS -- the Nature of Things Trans

REDUX EDITION* LUCRETIUS The Nature of Things Translated and with Notes by A. E. STALLINGS Introduction by RICHARD JENKYNS PENGUIN BOOKS * See the release notes for details LINE NUMBERING: The lines of the poem are numbered by tens, with the exception of line II.1021 which was marked instead of line II.1020 (unclear whether intended or by error) and the lines I.690 and I.1100 which were skipped altogether. The line numbering follows the 1947 Latin edition of Cyril Bailey and not this English translation (confusing but helpful when referencing other translations/commentaries). As stated in the "Note on the Text and Translation", the author joined together and restructured lines for the needs of this translation. Consequently, the number of actual lines between adjacent multiples of ten (or "decades") are often a couple of lines less or more than the ten of the referenced Latin edition. As far as line references in the notes are concerned, they are with maybe a few exceptions in alignment with the numbering of their closest multiple of ten. MISSING SECTIONS: As mentioned in the "Note on the Text and Translation", missing sections (or "lacunae") of which there are a few, are denoted with three dots and/or an explanation enclosed in square brackets. LINE STRUCTURE: The structure of the translation is rhymed couplets, meaning that you'll mostly (though not exclusively) have consecutive pairs of rhymed lines throughout the entire poem. The poem itself is broken up with occasional standard line breaks, as one would expect, but also with a more peculiar feature that might best be described as indented line breaks. -

Response to Request for Information

[NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED] Response to Request for Information Reference FOI 101587 Date 16 October 2015 Licensed Venues Request: Under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) we would like to request contact information for all Licensed Venues within your local authority. We would like an electronic copy only of this information, and would like the following included: Venue Name Address Owner name Landlord name Phone number Following reasonable enquiries, it has been established that the Council does not hold some of the above information. Consequently, we are unable to provide some of the information relating to the above, as per Section 1(1)(a) of the Act: "Any person making a request for information to a public authority is entitled to be informed in writing by the public authority whether it holds information of the description specified in the request". Additionl Description PLH Premises Address Post Code Bradmore Post Office & News Ravi Saini 17 Broad Lane WV3 9BN Sunridge News Ltd Sunridge News Ltd 34 Birchwood Road WV4 5UH Spice King Awlad Hussain 394 Penn Road WV4 4DF Sharma News Rajeev Kumar Sharma 130 Lime Street WV3 0EX Cosmo Midlands Investment Limited Unit B8 Bentley Bridge WV11 1UJ Heath Town Club Kirandeep Kaur Grewal Woden Road WV10 0AU Whetstone Green Convience Store Vinoshanth Alphonse Jayakumar 4a Whetstone Green WV10 9EZ Sing-Fellows Sing-fellows (Wton) Ltd 55-57 Lichfield Street WV1 1EQ 42/46 Mander Sq, Mander Discount UK PoundWorld Retail Limited Centre WV1 3NH Mr Sizzle Mr M A Smith, Mr SF Smith & Miss S L Smith -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 07 March 2016 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Dibble, Jeremy (2015) 'War, impression, sound, and memory : British music and the First World War.', German Historical Institute London bulletin., 37 (1). pp. 43-56. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.ghil.ac.uk/publications/bulletin/bulletin371.html Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk German Historical Institute London BULLETIN ISSN 0269-8552 Jeremy C. Dibble: War, Impression, Sound, and Memory: British Music and the First World War German Historical Institute London Bulletin, Vol 37, No. 1 (May 2015), pp43-56 WAR, IMPRESSION, SOUND, AND MEMORY: BRITISH MUSIC AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR JEREMY C. D IBBLE The First World War had a profound effect upon British music. -

1 General Manuscripts – by Location Location Content Date Oversize 1.001 Scott, Sir Walter

General Manuscripts – By Location Location Content Date Place of Creation Oversize Scott, Sir Walter A.L.S. to Alexander Balfour, a contemporary [s.d.] [s.l.] 1.001 (1771-1832) writer of novels and verse. Thanks Balfour for his praise and hoped that he would have Author been able to forward a new copy of a book of verse. With note explaining the provenance of the letter. Oversize ? Last will and testament in Latin. (Mutilated 1580 [Hungary?] 1.002 with severe loss of text.) Oversize Uhrfundeind, Ch. One certificate on parchment authenticating 1719 Dresden, [Germany] 1.003 Johann George the qualifications of a gardener; with the Dubel decorative armorial of Alessandro VII Chigi; hand water-coloured. Oversize Fraser, John Series of affidavits relating to the bankruptcy 1799 London 1.004 Merchant of of John Fraser, merchant, a property holder in Lower Canada the city of Quebec. Includes documents pertaining to William Henry Crowder, and Stephen Newman Oversize Sherbrooke Gold Declaration of Trust; Articles of Agreement 1866 New York 1.005 Mining between the Proprietors and Joint Association Stockholders; includes names of stockholders, number of shares owned by each and the amount they are to be paid. Oversize Arundell, Indenture for a transfer of lands between 1668 or 1678 England 1 1.006 Richard, Lord Arundell of Trevise and John Call. With a transcription in MS. Oversize Grand River Copy of list of subscribers with number of 1834 Upper Canada 1.007 Navigation shares bought and names of directors, Major Company Winniett, president; Samuel Street, William Richardson, Absolum Shade, W. Hamilton Merritt, and Six Nations of Indians. -

Religious Faith and Fear in Late Victorian Women's Poetry Sharon Lee George

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2011 The Pursuit of Divinity: Religious Faith and Fear in Late Victorian Women's Poetry Sharon Lee George Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation George, S. (2011). The urP suit of Divinity: Religious Faith and Fear in Late Victorian Women's Poetry (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/575 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PURSUIT OF DIVINITY: RELIGIOUS FAITH AND FEAR IN LATE VICTORIAN WOMEN‘S POETRY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Sharon L. George May 2011 Copyright by Sharon L. George 2011 THE PURSUIT OF DIVINITY: RELIGIOUS FAITH AND FEAR IN LATE VICTORIAN WOMEN‘S POETRY By Sharon L. George Approved April 1, 2011 ______________________________ ______________________________ Daniel P. Watkins, Ph.D. Laura Engel, Ph.D. Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) ______________________________ Kathy Glass, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) ______________________________ ______________________________ Cristopher M. Duncan, Ph.D. Magali Cornier Michael, Ph.D Dean, McAnulty College and Chair, Department of English Graduate School of Liberal Arts Professor of English iii ABSTRACT THE PURSUIT OF DIVINITY: RELIGIOUS FAITH AND FEAR IN LATE VICTORIAN WOMEN‘S POETRY By Sharon L. -

Negotiating Femininity As Spectacle Within the Victorian Cultural Sphere

CRACKED MIRRORS AND PETRIFYING VISION: NEGOTIATING FEMININITY AS SPECTACLE WITHIN THE VICTORIAN CULTURAL SPHERE by LUCINDA IRESON A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham November 2013 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Taking as it basis the longstanding alignment of men with an active, eroticised gaze and women with visual spectacle within Western culture, this thesis demonstrates the prevalence of this model during the Victorian era, adopting an interdisciplinary approach so as to convey the varied means by which the gendering of vision was propagated and encouraged. Chapter One provides an overview of gender and visual politics in the Victorian age, subsequently analysing a selection of texts that highlight this gendered dichotomy of vision. Chapter Two focuses on the theoretical and developmental underpinnings of this dichotomy, drawing upon both Freudian and object relations theory. Chapters Three and Four centre on women’s poetic responses to this imbalance, beginning by discussing texts that convey awareness and discontent before moving on to examine more complex portrayals of psychological trauma. -

Edward Lisle Strutt a Portrait

PETER FOSTER Edward Lisle Strutt A Portrait Lt Col Edward Lisle Strutt’s portrait as president of the Alpine Club. nflexible in opinion, outspoken and totally unmoved by the changing ‘Itimes through which he lived’1, ‘a complex and difficult man, certain of his own opinions… pompous and arrogant;’2 ‘he is remembered not for his climbing or his absorbing journals but for his virulent antipathies.’3 This is a short selection from numerous similar epithets applied to Lt Col Edward Lisle Strutt (1874-1948), ‘Bill’ to his friends, editor of the Alpine Journal from 1927 to 1937 and president of the Club from 1935 to 1937. 1. W Unsworth, Everest, 3rd ed, London, Bâton Wicks, 2000, p72. 2. W Davis, Into the Silence, London, Bodley Head, 2011, p379. 3. S Goodwin, ‘The Alpine Journal: A Century and a Half of Mountaineering History’, Himalayan Journal 60, 1. 189 512j The Alpine Journal 2019_Inside.indd 189 27/09/2019 10:57 190 T HE A LPINE J OURN A L 2 0 1 9 Strutt on Everest in 1922, sitting on Charles Bruce’s left. ‘It may possibly be,’ Bruce said of Strutt, ‘that we are a little too young for him.’ Strutt’s mother made sure he was At St Moritz in 1904. ‘Life for a raised a Catholic, despite his father, member of the leisured upper class who died in an industrial accident in Edwardian England remained when Strutt was three, insisting most agreeable.’ on him being raised an Anglican. In the years between the wars the Alpine Club lost the leadership of the alpine world and Strutt’s reactionary views, expressed intemperately in the pages of the Journal, contributed to the decline in the Club’s prestige. -

House and Home in Late Victorian Women's Poetry

HOUSE AND HOME IN LATE VICTORIAN WOMEN'S POETRY BEING A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D IN THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL BY KATHARINE MARGARET MCGOWRAN BA(HONS), MA SEPTEMBER 1999 We flatter ourselves with fancied freedom. We are the slaves of every house that belongs to us. Invisible chains bind us to every chair and table. No sooner have we got rid of them than we begin to long for bonds afresh. (Mary E. Coleridge, Non Sequitur, 1907: 108) Contents Preface 1 1. The Social and Literary Context 4 2. `Echoes... queries... reactions... afterthoughts: Nostalgia and Homesickness 29 3. The Haunted House: Rossetti, Nesbit, Marriott Watson 53 86 4. The House of Poetry: Mary E. Coleridge 5. The House of Art: Mary E. Coleridge 112 6. At the Cross-Roads: Amy Levy 140 7. The Empty House: Charlotte Mew 166 References and bibliography 188 1 Preface Any consideration of the theme of `house and home' leads into discussion on three different levels of discourse. First of all, houseshave biographical and historical significance; they are, after all, real places in which real lives are lived. Secondly, home is an ideologically loaded noun, a bastion of value which is inextricably entwined with the notion of the pure woman. Thirdly, in literature, houses are metaphorical places. This thesis is primarily a study of those metaphorical places. It explores representationsof `house' and `home' in late Victorian women's poetry. However, it also takes account of the biographical, historical and ideological significance of the house, looking at factors which may have helped to shape each poet's representationsof `house and home'. -

The Travelling Companion

The Travelling Companion Programme The Travelling Companion Opera in Four Acts by Charles Villiers Stanford Portrait by William Orpen, Trinity College Cambridge Portrait by William Orpen, after a story by Hans Christian Andersen libretto by Henry Newbolt First performance: David Lewis Theatre, Liverpool 30 April 1925 First performance of this production: Lewes Town Hall 21 November 2018 then at Devonshire Park Theatre, Eastbourne; Cadogan Hall, London; Saffron Hall, Saffron Walden (the final performance will be recorded live for release by SOMM, the first recording of any of Stanford’s nine operas) Production supported by The Stanford Society, John Lewis and Partners, The Behrens Foundation, Lewes Town Council www.newsussexopera.org NSO 1978—2018 “One of the UK’s most enterprising small opera Fidelio companies, New Sussex Opera constantly surprises Venus and Adonis Boris Godunov with its ambition and the quality of its fully staged The Fairy Queen Opera Now September 2018 –Autumn highlights Peter Grimes productions.” The Queen of Spades NSO presents Stanford’s The Travelling important as we use a variety of venues and The Threepenny Opera Companion, a rare opportunity to hear would like to keep you in touch with our news. Il trittico a fascinating work which has not had a Opera is the most expensive of art forms Andrea Chénier professional production for over eighty and for forty years NSO has survived Benvenuto Cellini years. We welcome our new conductor without subsidy. If you like what we do, and Aida Toby Purser and director Paul Higgins. would like to see more of it, please help us A Masked Ball We warmly thank John Covell and the The Flying Dutchman achieve even more.