The Pacific: 1945 HISTORYHIT.COM 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Ships and Submarines of the United States Navy

AIRCRAFT CARRIER DDG 1000 AMPHIBIOUS Multi-Purpose Aircraft Carrier (Nuclear-Propulsion) THE U.S. NAvy’s next-GENERATION MULTI-MISSION DESTROYER Amphibious Assault Ship Gerald R. Ford Class CVN Tarawa Class LHA Gerald R. Ford CVN-78 USS Peleliu LHA-5 John F. Kennedy CVN-79 Enterprise CVN-80 Nimitz Class CVN Wasp Class LHD USS Wasp LHD-1 USS Bataan LHD-5 USS Nimitz CVN-68 USS Abraham Lincoln CVN-72 USS Harry S. Truman CVN-75 USS Essex LHD-2 USS Bonhomme Richard LHD-6 USS Dwight D. Eisenhower CVN-69 USS George Washington CVN-73 USS Ronald Reagan CVN-76 USS Kearsarge LHD-3 USS Iwo Jima LHD-7 USS Carl Vinson CVN-70 USS John C. Stennis CVN-74 USS George H.W. Bush CVN-77 USS Boxer LHD-4 USS Makin Island LHD-8 USS Theodore Roosevelt CVN-71 SUBMARINE Submarine (Nuclear-Powered) America Class LHA America LHA-6 SURFACE COMBATANT Los Angeles Class SSN Tripoli LHA-7 USS Bremerton SSN-698 USS Pittsburgh SSN-720 USS Albany SSN-753 USS Santa Fe SSN-763 Guided Missile Cruiser USS Jacksonville SSN-699 USS Chicago SSN-721 USS Topeka SSN-754 USS Boise SSN-764 USS Dallas SSN-700 USS Key West SSN-722 USS Scranton SSN-756 USS Montpelier SSN-765 USS La Jolla SSN-701 USS Oklahoma City SSN-723 USS Alexandria SSN-757 USS Charlotte SSN-766 Ticonderoga Class CG USS City of Corpus Christi SSN-705 USS Louisville SSN-724 USS Asheville SSN-758 USS Hampton SSN-767 USS Albuquerque SSN-706 USS Helena SSN-725 USS Jefferson City SSN-759 USS Hartford SSN-768 USS Bunker Hill CG-52 USS Princeton CG-59 USS Gettysburg CG-64 USS Lake Erie CG-70 USS San Francisco SSN-711 USS Newport News SSN-750 USS Annapolis SSN-760 USS Toledo SSN-769 USS Mobile Bay CG-53 USS Normandy CG-60 USS Chosin CG-65 USS Cape St. -

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of An

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with WESLEY S. TODD Fighter Pilot, Marine Corps, World War II. 1997 OH 337 1 OH 337 Todd, Wesley S b. (1921) Oral History Interview, 1997. User Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 90 min.), analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 90 min.), analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder) Abstract: Wesley Todd, a Wauwatosa, Wisconsin native, discusses his service as a Marine Corps fighter pilot in the Pacific during World War II. A student at the Citadel Military Academy (Charleston, South Carolina) when the war began, Todd talks of learning to fly through the Hawthorne Flying Service, his freshman orientation course, cadet training, and joining the Navy V5 program during his junior year. He mentions regional tensions, being considered a “Yankee,” and not being allowed to eat one night after a showing of “Gone With the Wind.” He received pre-flight instruction in Iowa City (Iowa), primary training at Glenview, advanced flying in Corpus Christi (Texas), and his commission as a Marine Corps second lieutenant. Volunteering to fly fighter aircraft, he learned to fly F4U Corsairs in the Mojave Desert. He speaks briefly of his first assignment to a torpedo-bomber squadron in Jacksonville, Florida. Joining the USS Essex, he comments on flying strikes against the Tokarizawa and Koisumi airfields near Tokyo, providing air cover for the landing at Iwo Jima, and covering the landing at Okinawa. He details the Okinawa campaign and tells of dropping important messages on the USS El Dorado during the struggle for Iwo Jima. -

Segunda Guerra Mundial 63 Fatos E Curiosidades Sobre a Guerra Mais Sangrenta Da História 1ª Edição

2 LIVROS EM 1 + Coleção Segunda Guerra Mundial 63 Fatos e Curiosidades Sobre a Guerra Mais Sangrenta da História 1ª edição Coleção: Histórias de Guerra A Ler+ Digital uma editora focada em produzir conteúdo de qualidade para leitores curiosos e amantes de boas histórias. Acreditamos que o acesso ao conhecimento pode libertar a mente humana e potencializar suas ações, visando evoluir continuamente. As obras criadas pela editora Ler+ Digital tem como objetivo nutrir mentes curiosas, dispostas a aprender e compartilhar histórias interessantes e de grande valor. Ler mais é fundamental, Ler+ Digital é a sua melhor escolha. 1. O Sobrevivente Dos Ataques Nucleares De Hiroshima E Nagasaki Tsutomu Yamaguchi, sobrevivente dos dois ataques nucleares de Hiroshima e Nagasaki O japonês Tsutomu Yamaguchi, pode ser considerado muito azado ou muito sortudo. Muito azarado porque ele esteve presente nas cidades de Hiroshima e Nagasaki, no dia em que elas foram atingidas por bombas atômicas. Muito sortudo porque conseguiu sobreviver aos dois eventos. Yamaguchi era residente de Nagasaki, mas estava em viagem de negócios por Hiroshima, e ficaria por lá durante todo o verão de 1945. Na manhã do dia 6 de agosto, ele estava próximo ao cais da cidade trabalhando enquanto ouvia notícias sobre a guerra e o avanço inimigo. Quando o relógio marcou 8:15 da manhã, a bomba atômica Little Boy foi detonada, causando a primeira explosão nuclear durante confronto da história, devastando a cidade e ceifando mais de 100 mil vidas, quase instantaneamente. Yamaguchi estava próximo ao local da explosão e sentiu o calor e o impacto da explosão, sofrendo graves lesões internas, tímpanos estourados, queimaduras por todo lado esquerdo do corpo, além de perder uma parte da visão. -

NHK Spring Report 2011

NHK Spring Report 2011 NHK Spring Report 2011 Society·Environment·Finance April 2010 — March 2011 For a resilient society through a wide-range of innovation across Society·Environment·Finance a diversity of fields April 2010 — March 2011 We, the people of NHK Spring, follow our Corporate Philosophy, in the spirit of our Corporate Slogan: Corporate Slogan NHK Spring— Progress. Determination. Working for you. Corporate Philosophy Building a better world To contribute to an affluent society through by building innovative products an attractive corporate identity by applying innovative ideas and practices, based on a global perspective, that bring about corporate growth. Contact: Public Relations Group, Corporate Planning Department NHK SPRING CO., LTD. 3-10 Fukuura, Kanazawa-ku, Yokohama, 236-0004, Japan TEL. +81-45-786-7513 FAX. +81-45-786-7598 URL http://www.nhkspg.co.jp/index_e.html Email: [email protected] KK201110-10-1T NHK Spring Report 2011 NHK Spring Report 2011 Society·Environment·Finance April 2010 — March 2011 For a resilient society through a wide-range of innovation across Society·Environment·Finance a diversity of fields April 2010 — March 2011 We, the people of NHK Spring, follow our Corporate Philosophy, in the spirit of our Corporate Slogan: Corporate Slogan NHK Spring— Progress. Determination. Working for you. Corporate Philosophy Building a better world To contribute to an affluent society through by building innovative products an attractive corporate identity by applying innovative ideas and practices, based on a global perspective, that bring about corporate growth. Contact: Public Relations Group, Corporate Planning Department NHK SPRING CO., LTD. 3-10 Fukuura, Kanazawa-ku, Yokohama, 236-0004, Japan TEL. -

Tsutomu Yamaguchi

ILMUIMAN.NET: Koleksi Cerita, Novel, & Cerpen Terbaik Mini Biografi (16+). 2018 (c) ilmuiman.net. All rights reserved. Berdiri sejak 2007, ilmuiman.net tempat berbagi kebahagiaan & kebaikan.. Seru. Ergonomis, mudah, & enak dibaca. Karya kita semua. Terima kasih & salam. *** Tsutomu Yamaguchi Bom Atom Nggak Terima Satu... Bismillahirrahmanirrahiim... Tanpa niatan mengagung-agungkan perang, atau mengagungkan siapapun, Sekedar berbagi satu kisah kecil, unik menurut penulis. Semoga, memberi inspirasi bagi kita semua untuk senantiasa optimis dan bersyukur, mensyukuri kehidupan ini... Di balik bom atom di Hiroshima dan Nagasaki,.. ada banyak kisah anak manusia. Kisah besar, ataupun kecil. Ini salah satu di antaranya... ... Ada nggak sih, orang yang udah kena bom (atom) di Hiroshima, terus nggak meninggal, malah terus pergi ke Nagasaki, dan kena bom atom lagi di sana? Ada ternyata! Menurut pendapat umum di Jepang, yang seperti itu (kena bom atom 2x) ada 69 orang. Atau ada yang bilang 165. Tapi, yang beneran diakui pemerintah (secara resmi) sebagai korban yang kena dua-duanya, itu cuma satu. Namanya: Tsutomu Yamaguchi! Aslinya, Tsutomu Yamaguchi itu penduduk Nagasaki. Alkisah, di hari pemboman Hiroshima, dia itu diminta oleh perusahaan tempat dia kerja (yaitu Mitsubishi Heavy Industries) untuk spj ke Hiroshima. Begitu nyampe Hiroshima, bum! Bom atom menghajar Hiroshima jam 8:15 pagi, 6 Agustus 1945. Dia terdampak dan terluka cukup parah. Cacat seumur idup boleh dibilang. Cuma nekat, besoknya tetep pulang ke Nagasaki, dan bahkan masih dalam keadaan kopyor, 9 Agustus dia masuk kerja. Oleh boss-nya, dia sempat dikatai gila saat menceritakan, bahwa Hiroshima.. satu kota penuh, dihancurkan hanya oleh bom sebiji. "Iya, sih. Dikau kena bom sekutu di Hiroshima, kite maklum. -

Closingin.Pdf

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead. -

Nuclear Thermal Propulsion Risk Communication

Nuclear Thermal Propulsion Risk Communication NETS 2015 February 25 Predecisional: For Planning Purposes Only www.nasa.gov NTR Full Scale Development (FSD) Risks conse- Risk ID Risk Definition likelihood quence 5 Radical irrational public & political 1 5 4 L FEAR toward space nuclear systems Regulatory Process becomes too I 2 variable variable cumbersome and affect schedule K 4 6 10 4 1 Security requirement drive 3 5 2 E development COST too high L CFM LH2 zero-boil-off, QD & no 4 5 4 leakage technology for FSD I 3 2 Nuclear Fuel Element technology not H 5 5 1 O ready for FSD Changing ground test requirements O 6 3 4 8 7 due to respond to peoples fears D 2 3 7 Turbopump FSD schedule 4 2 Autonomous Vehicle System 8 Management technology not ready 1 2 9 5 1 for prototype flight Deep-Space Spacecraft System 9 technology (radiation protection) not 3 1 ready for FSD 1 2 3 4 5 . NCPS FSD schedule is longer than 4 CONSEQUENCES 10 years and political winds start/stop 4 4 progress A notional 5X5 Risk Matrix for Nuclear Thermal Rocket Full Scale Development 2 A Vision for NASA’s Future … President John F. Kennedy … • First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth…. • Secondly, an additional 23 million dollars, together with 7 million dollars already available, will accelerate development of the Rover nuclear Excerpt from the 'Special Message to the rocket. -

Reminiscences of Vice Admiral Andrew Mcburney Jackson, Jr. US

INDEX to Series of Interviews with Vice Admiral Andrew McBurney JACKSON, Jr. U. S. Navy (Retired) ADEN: p. 274-5; AEC (Atomic Energy Commission): Jackson to AEC (Military Application Division), p. 154-5; works with Admirals Hooper and Withington, p. 157; setting up Sandia base, p. 158-9; defense of AEC budget before Congressional Committees, p. 162-3; p. 170-1; discussion of clearances at AEC p. 165-6; p. 167-8; AIR GROUP 8: Jackson ordered (1943) to re-form air group p. 93; duty on INTREPID, p. 96; component parts in Norfolk area, p. 96-7; Air Group 5 substituted for Air Group 8 - Marshall Islands operation, p. 103 ff; Air Group 8 put aboard BUNKER HILL when INTREPID goes home for repairs, p. 105; ANDERSON, Admiral George: p. 313 p. 315; p. 321; ARAB-ISRAELI HOSTILITY: p. 298-9; ARAMCO: p. 279-80; ATOM BOMB: an exercise with aircraft carrier, p. 182-3; AUSTIN, VADM Bernard (Count): President of the Naval War College (1961), p. 299-300; BAHREIN: p. 253-4; p. 280; p. 282-4; BALL, The Hon. George: U. S. Representative to the United Nations, p. 377; BATON ROUGE, La.: family home of Adm. Jackson, p. 2-4; BETHPAGE, N.Y.: location of Grumman plant on Long Island - see entries under BuAir; BOGAN, VADM Gerald F.: succeeds Adm. Montgomery as skipper of BUNKER HILL, p. 118; BuAIR: Jackson ordered to Bureau (June 1941) to fighter desk (Class Desk A), p. 70 ff; plane types, p. 73-4 ff; his great desire to go with Fleet after Pearl Harbor, p. -

World at War and the Fires Between War Again?

World at War and the Fires Between War Again? The Rhodes Colossus.© The Granger Collection / Universal Images Group / ImageQuest 2016 These days there are very few colonies in the traditional sense. But it wasn't that long ago that colonialism was very common around the world. How do you think your life would be different if this were still the case? If World War II hadn’t occurred, this might be a reality. As you've already learned, in the late 19th century, European nations competed with one another to grab the largest and richest regions of the globe to gain wealth and power. The imperialists swept over Asia and Africa, with Italy and France taking control of large parts of North Africa. Imperialism pitted European countries against each other as potential competitors or threats. Germany was a late participant in the imperial game, so it pursued colonies with a single-minded intensity. To further its imperial goals, Germany also began to build up its military in order to defend its colonies and itself against other European nations. German militarization alarmed other European nations, which then began to build up their militaries, too. Defensive alliances among nations were forged. These complex interdependencies were one factor that led to World War I. What Led to WWII?—Text Version Review the map description and the descriptions of the makeup of the world at the start of World War II (WWII). Map Description: There is a map of the world. There are a number of countries shaded four different colors: dark green, light green, blue, and gray. -

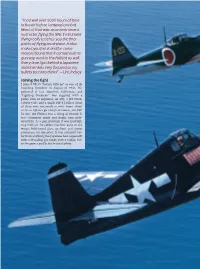

I Had Well Over 1000 Hours of Time in the Air Before I

“I had well over 1,000 hours of time in the air before I entered combat. Most of that was as an instrument instructor fl ying the SNJ. Instrument fl ying really teaches you the fi ner points of fl ying an airplane. It also makes you focus and for some reason I found that it carried over to gunnery work in the Hellcat as well. Every time I got behind a Japanese airplane I was very focused as my bullets tore into them!” —Lin Lindsay Joining the fi ght I joined VF-19 “Satan’s Kittens” as one of its founding members in August of 1943. We gathered at Los Alamitos, California, and “Fighting Nineteen” was supplied with a paltry sum of airplanes; an SNJ, a JF2 Duck, a Piper Cub, and a single F6F-3 Hellcat. Most of them were not much to write home about as far as fi ghters go except of course, the F6F. To me, the Hellcat was a thing of beauty. It was Grumman made and damn near inde- structible! As a gun platform it was hard hit- ting with six .50 caliber machine guns in the wings, bulletproof glass up front and armor protection for the pilot. It was certainly bet- ter than anything the Japanese had, especially with self-sealing gas tanks, better radios, bet- ter fi repower and better trained pilots. 24 fl ightjournal.com Bad Kitty.indd 24 5/10/13 11:51 AM Bad KittyVF-19 “Satan’s Kittens” Chew Up the Enemy BY ELVIN “LIN” LINDSAY, LT. -

World War II

World War II 1. What position did George Marshall hold during World War II? A. Commanding General of the Pacific B. Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army C. Army Field Marshall of Bataan D. Supreme Officer of European Operations 2. Which of the following best explains why President Harry S. Truman decided to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II? A. He wanted the war to last as long as possible. B. He wanted to wait for the USSR to join the war. C. He wanted Germany to surrender unconditionally. D. He wanted to avoid an American invasion of Japan. 3. What impact did the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor have on World War II? A. Italy surrendered and united with the Allies. B. The Pacific Charter was organized against Japan. C. Japan surrendered to the Allies the following day. D. It pulled the United States into World War II. 4. The picture above is an iconic image from World War II and symbolizes which of the following? A. the women who ferried supplies into combat areas during the war B. the millions of women who joined the workforce in heavy industry C. the important work done by Red Cross nurses during World War II D. the women who joined the armed forces in combat roles Battle of the Bulge The Battle of the Bulge, initially known as the Ardennes Offensive, began on December 16, 1944. Hitler believed that the coalition between Britain, France, and the United States in the western region of Europe was not very powerful and that a major defeat by the Germans would break up the Allied forces. -

World War II 1931 - 1945

World War II 1931 - 1945 The Treaty of Versailles • Germany lost land to surrounding nations • War reparations – Allies collect $ to pay back war debts to US – Germany pays $57 trillion (modern day equivalent) – Germans are bankrupt, embarrassed, guilt ridden, and angry. The Rise of Dictators The legacy of World War I and the effects of the Great Depression led to mass unemployment, inflation, and the threat of communism in Europe. These factors caused widespread political unrest. The Rise of Dictators Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler preached that became known as . Mussolini became prime minister of Italy in 1922 and soon established a dictatorship. Hitler and his Nazi Party won control of the German government in 1933 and quickly overthrew the nation’s constitution. The Rise of Dictators By 1929, Joseph Stalin was dictator of the Soviet Union, which he turned into a totalitarian state. Stalin took brutal measures to control and modernize industry and agriculture. Stalin had four million people killed or imprisoned on false charges of disloyalty to the state. The Spanish Civil War The Spanish Civil War offered an opportunity to test the new German military tactics and the strategy of Die Totale Krieg (The Total War). Japanese Aggression General Hideki Tōjō was the Prime Minister of Japan from 1941 to 1944. In 1931, military leaders urged the to invade Manchuria, a province in northern China that is rich in natural resources. Italian Aggression In 1935, ordered the invasion of Ethiopia. Italian troops roared in with machine guns, tanks, airplanes, and chemical weapons quickly overwhelming the poorly equipped Ethiopian army and killing thousands of civilians.