Fraser Wilkins Interviewer: William W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963 Middle East First Supplement A UPA Collection from Cover: Map of the Middle East. Illustration courtesy of the Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook. National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring The John F. Kennedy National Security Files, 1961–1963 Middle East First Supplement Microfilmed from the Holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Guide by Dan Elasky A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road ● Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. Middle East, First supplement [microform] / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. –– (National security files) “Microfilmed from the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts.” Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Dan Elasky, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. Middle East, First supplement. ISBN 1-55655-925-9 1. Middle East––Politics and government––1945–1979––Sources. 2. United States–– Foreign relations––Middle East. 3. Middle East––Foreign relations––United States. 4. John F. Kennedy Library––Archives. I. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of the John F. Kennedy national security files, 1961–1963. Middle East, First supplement. II. Series. DS63.1 956.04––dc22 2007061516 Copyright © 2007 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier -

Us Military Assistance to Saudi Arabia, 1942-1964

DANCE OF SWORDS: U.S. MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO SAUDI ARABIA, 1942-1964 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce R. Nardulli, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn _______________________ Adviser Professor David Stebenne History Graduate Program UMI Number: 3081949 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081949 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The United States and Saudi Arabia have a long and complex history of security relations. These relations evolved under conditions in which both countries understood and valued the need for cooperation, but also were aware of its limits and the dangers of too close a partnership. U.S. security dealings with Saudi Arabia are an extreme, perhaps unique, case of how security ties unfolded under conditions in which sensitivities to those ties were always a central —oftentimes dominating—consideration. This was especially true in the most delicate area of military assistance. Distinct patterns of behavior by the two countries emerged as a result, patterns that continue to this day. This dissertation examines the first twenty years of the U.S.-Saudi military assistance relationship. It seeks to identify the principal factors responsible for how and why the military assistance process evolved as it did, focusing on the objectives and constraints of both U.S. -

The Gordian Knot: American and British Policy Concerning the Cyprus Issue: 1952-1974

THE GORDIAN KNOT: AMERICAN AND BRITISH POLICY CONCERNING THE CYPRUS ISSUE: 1952-1974 Michael M. Carver A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2006 Committee: Dr. Douglas J. Forsyth, Advisor Dr. Gary R. Hess ii ABSTRACT Douglas J. Forsyth, Advisor This study examines the role of both the United States and Great Britain during a series of crises that plagued Cyprus from the mid 1950s until the 1974 invasion by Turkey that led to the takeover of approximately one-third of the island and its partition. Initially an ancient Greek colony, Cyprus was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th century, which allowed the native peoples to take part in the island’s governance. But the idea of Cyprus’ reunification with the Greek mainland, known as enosis, remained a significant tenet to most Greek-Cypriots. The movement to make enosis a reality gained strength following the island’s occupation in 1878 by Great Britain. Cyprus was integrated into the British imperialist agenda until the end of the Second World War when American and Soviet hegemony supplanted European colonialism. Beginning in 1955, Cyprus became a battleground between British officials and terrorists of the pro-enosis EOKA group until 1959 when the independence of Cyprus was negotiated between Britain and the governments of Greece and Turkey. The United States remained largely absent during this period, but during the 1960s and 1970s came to play an increasingly assertive role whenever intercommunal fighting between the Greek and Turkish-Cypriot populations threatened to spill over into Greece and Turkey, and endanger the southeastern flank of NATO. -

BOMBS EXPLODE in US EMF, A'ssy--U~ I~ E;-; Xec~ H.~~: Bo~ Rd

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives 2-5-1964 Kabul Times (February 5, 1964, vol. 2, no. 283) Bakhtar News Agency Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bakhtar News Agency, "Kabul Times (February 5, 1964, vol. 2, no. 283)" (1964). Kabul Times. 545. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes/545 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Newspaper Archives at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kabul Times by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - , .. ~ "- I -. ..... ,. 'y , ,. '. ... - '"" ~ - " : • ., -FEBR"UARY, 4, 1964 '. ,- I TIMES " PAGE 4 .<i THE WEATHER -- .}., --, '. Afghanistiin, West German Firms Sign o' YESTERDAY M~x -12°C. Home News In ~I\Iinimum - . ~ ~tws Sl'ALt-S ': - ". EVE~" O·C. ;:'5ar,e,n~w;· Kh~ber-- o CYPRUS )~ ~ Sun sets today at 5- ~9 p.m Resfaumt ... ... ContJ~-acts ·....O~ Mahipar Power Project , >, ),e:u -Sh3;li Pu(~ iYue' lHoSque «(;Ontd. from oage It~ . i Brief ..,~ Sun rises tomorrow at &-:35 a,m. tn~:J .'- t ' •, "'-T Tomorrow's OutlOOk' ':1 lif:.nai ClclJ; ?':>mir qroeill.l 0: lr;e gO\ ernmen I. , r 5 KABUL, Feb 4.-The Pashtani .~-=- SHghtly cloudv . , " Tur :Ish officials last ;..::.D.lght I '. .~h"t Tejarat1 -Bank held a reception -ForecaSt by Air Aothuiity , ,rre<!'eli Turkey W6'fJd be '- I • lD honour of two ViSiting ~. ( ,10; \;lIe of }andm~ ,,~ -least 20.000 -- last mght m the \'OL II, NO 283 --- ·ncr. -

The Foreign Service Journal, September 1943

9L AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE VOL. 20, NO. 9 JOURNAL SEPTEMBER, 1943 . Jt * - - L ' 's-:' t*Z American to the core, I. W. Harper whiskey has been winning gold medals at international expositions for many generations. Unexcelled taste and quality are the reasons . cost is never consulted in making this superb whiskey. It’s one of the best reasons why world sales of American whiskies top those of all whiskies made elsewhere. Bernheim Distilling Company, Inc., Louisville, Kentucky, U. S. A. THERE ARE NO FINER WHISKIES THAN AMERICAN WHISKIES This rallying cry is appearing in I.W. HARPER Schenley advertising throughout Latin America. THE GOLD MEDAL WHISKEY CONTENTS SEPTEMBER, J94.'5 AMERICAN EASTERN Cover Picture: Seagulls over the Alaskan coast. TRADING & SHIPPING C0.,S.A.E. The Alaska Highway 449 Alexandria and Suez (Egypt) By John Randolph Branches or Agents in: Martinique—photos 453 Alexandria Jaffa By George D. Lamont Cairo Jerusalem Port Said Haifa Suez Beirut Preparedness for Peace 454 Port Sudan Iskanderon By Donald D. Edgar Khartoum Damascus Djibouti Ankara New Caledonia 456 Addis Ababa Izmir By Captain Aleck Richards Jedda Istanbul Nicosia Codthaab. Greenland—photos 458 By John B. Ocheltree AMERICAN IRAQI SHIPPING CO., LTD. Allied Military Currency 459 (Only American-Owned Shipping Firm in Persian Gulf) Claims by the Foreign Service for War Losses —continued 560 Basrah and Baghdad (Iraq) Editor’s Column 462 Branches or Agents in: News from the Department 463 Baghdad Bandar Abbas By Jane Wilson Basrah Teheran Khorramshahr Bahrein Bandar Shahpour Ras Tannurah News from the Field 466 Abadan Koweit Bushire Mosul Promo lions 468 Service Glimpses 469 The Bookshelf 474 Francis C. -

Coercive State, Resisting Society, Political and Economic Development in Iran Mehrdad Vahabi

Coercive state, resisting society, political and economic development in Iran Mehrdad Vahabi To cite this version: Mehrdad Vahabi. Coercive state, resisting society, political and economic development in Iran. 2017. hal-01583595 HAL Id: hal-01583595 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01583595 Preprint submitted on 7 Sep 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. .......................... Centre d'économie de l'Université Paris Nord CEPN CNRS UMR n° 7234 Document de travail du CEPN N°2017-17 Axe principal : Santé Société et Migrations Axe secondaire : Macroéconomie Appliquée Finance et Mondialisation Coercive state, resisting society, political and economic development in Iran Mehrdad Vahabi, CEPN, UMR-CNRS 7234, Université Paris 13, Sorbonne Paris Cité [email protected] September 2017 Abstract: In my studies, I have explored the political economy of Iran and particularly the relationship between the state and socio-economic development in this country. The importance of the oil revenue in economic development of contemporary Iran has been underlined since the early seventies and a vast literature on the rentier state and authoritarian modernization has scrutinized the specificities of the political and economic natural resource ‘curse’ in Iran. -

Ambassador Wells Stabler

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR WELLS STABLER Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 28, 1991 Copyright 1998 A ST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Boston Massachusetts" Raised in the U.S. and abroad Harvard University Entered Foreign Service State Department - Inter American Affairs 19,1-19,3 Ecuadoran desk officer .elson Rockefeller involvement A/is South American strongholds Sumner 0ells 1ordell Hull 0artime 2black lists2 Post-0ar Programs 1ommittee - Assistant Secretary 19,, Political vs. economic discussions Secretary of State Stettinius Policy for post-3ar Europe and Asia 4erusalem - 5ice 1onsul 19,,-19,8 7etting there 0artime 4erusalem Environment 4e3s and Arabs 2truce2 8ing David Hotel e/plosion and aftermath 1onsulate jurisdiction 5isit to Emir Abdullah 1onsul 7eneral Pinkerton Anglo-American 1ommittee of In9uiry Operations and duties Terrorism British Arab sympathies OSS advisor 1 U.7A Partition Resolution British 3ithdra3al - 19,8 1onsulate guard detachment State unresponsive to needs 1onsul 7eneral Tom 0asson killed Political reporting ;ionists U.S. recognition of Israel Partition Plan - 19,7 Arab-Israel 3ar in 4erusalem 1onsular casualties 1ount Bernadotte - U. Mediator Amman 4ordan - American Representative - 1hargé d'Affaires 19,8-19,9 8ing Abdullah Sir Alec 8irkbride U.S. recognition of 4ordan 2Hashemite 8ingdom of 4ordan2 4ordan-British relations U. Trustee 1ouncil - U.S. Representative 1950 InternationaliAation of -

The Foreign Service Journal, March 1942

qL AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE VOL. 19, NO. 3 JOURNAL MARCH, 1942 *» SUPER Performance for the SUPER Cruiser Lycoming leadership in building engines for Free literature on request for SO to 175 h.p. hori¬ zontally opposed or 220 to 300 h.p. radial engines. America’s training planes is important to Write Dept. J32. Specify which literature desired. civilian as well as military aviation. In the Piper Super Cruiser the 100 h.p. Lycoming horizontally opposed engine provides depend¬ able performance for pilot training, instru¬ ment instruction and Civil Air Patrol flying. CONTENTS MARCH, 1942 Cover Picture: Conning Tower of a Dutch Warship in the Pacific Ocean. (See page 173) The Netherlands East Indies at War By Dr. H. van Houten 125 A good neighbour... Rio Conference of Foreign Ministers—Photos.... 130 Selected Questions from the Third General For¬ and a good mixer! eign Service Examination of 1941 131 Townsend Harris Helped Open Japan to Trade.. 135 The Air Training Plan of the British Common¬ Si senor! For BACARDI is not only an wealth outstanding example of Pan-American By an Officer of the R.C.A.F 136 solidarity in the realm of good taste, Mural Paintings at the Mexican Embassy in but the most congenial and versatile Washington—Photos 140 of all the great liquors of the world. Editors’ Column Amendment of Civil Service Retirement Act 142 It mixes readily and superbly with all fine ingredients, from the sparkling News from the Department By Jane Wilson 143 simplicity of a highball to the compli¬ Organization of the Department of State 145 cated art of a Coronation Cocktail.. -

Interview with Ambassador Fraser Wilkins

Library of Congress Interview with Ambassador Fraser Wilkins The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR FRASER WILKINS Interviewed by: Peter Jessup Initial Interview Date: July 21, 1988 Copyright 2010 ADST [Note: Ambassador Wilkins died in January 1989, before having an opportunity to edit this transcript. The Oral History Program has made light changes in the transcription regarding punctuation and has filled in some names.] Q: I was saying that you graduated from Yale in the class of '31, and then you entered business, and you were in Kentucky for a while, weren't yoFrankfurt Distilleries and so forth? What prompted you to get into the Foreign Service? Were there any particular influences at New Haven, or among classmates that led you into that field? And did any of them follow you in? WILKINS: There's a little prologue to the last part of your statement. I was born in Omaha, Nebraska, on the hot day of August 31, 1908. Rather different than the muggy days of Washington in 198almost 80 years ago. It was the custom in Omaha, in those days, for young boys of middle class families to go east to college. Actually, to go east to prep school, and then to college. In accordance with this custom I went to The Hill School in 1922, having previously lived in Chicago from 1910. My father moved back to Omaha, having been a vice president of Cudahy Packing Company. Mr. Cudahy had moved to Chicago in 1910, and between 1917 and 1922 Interview with Ambassador Fraser Wilkins http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib001666 Library of Congress moved back to Omaha because he didn't like the Stockyards in Chicago. -

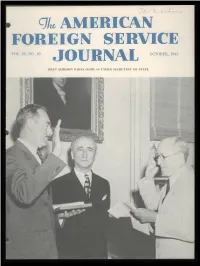

The Foreign Service Journal, October 1945

J/4 ~ ~7)w 9.L AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE VOL. 22, NO. 10 JOURNAL OCTOBER, 1945 DEAN ACHESON TAKES OATH AS UNDER SECRETARY OF STATE Sra/e/u/ ?yJc/oioiv/ef/qp/neiif . For the part that the American Foreign sonal use, to those peoples among whom Service has played in expanding the de¬ you temporarily reside. And we are proud mand for American products abroad, every to serve a group such as yours. American exporter offers sincere thanks. Gentlemen: a toast! May you never The makers of Three Feathers Whiskey run short of Three Feathers, that very are no exception. special American whiskey, long a favorite We appreciate not only your official here at home! activities, so important in planning and THREE FEATHERS DISTRIBUTORS, Inc. obtaining distribution. We are also grateful Empire State Bldg. THREE FEATHERS for the example you have set, by your per¬ New York THE AMERICAN WHISKEY PAR EXCELLENCE CONTENTS Cover Picture: The Honorable Dean Acheson was sworn in as Under Secretary of State on August 27, 1945, by BARR SERVICE F.S.O. James McKenna, Special Assistant to the Director of Office of Public Affairs, in the pres¬ Thirty Years of Continuous Service to ence of Secretary Byrnes. Exporters and Importers The Berlin Conference 7 By George V. Alien • Vindication of John S. Service 12 By Garnett D. Horner International Public Relations- The Spearhead of Diplomacy.... 15 SHIPPING AGENTS By Francis Russell Statement of Ownership, Management, Circula¬ FOREIGN FREIGHT FORWARDERS tion, etc 16 FREIGHT AND CUSTOM HOUSE Statistical Survey of the Foreign Service, Part I... -

White House Special Files Box 20 Folder 8

Richard Nixon Presidential Library White House Special Files Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date Document Type Document Description 20 8 N.D. Report Staffing Status Report for the Navy. 1 pg. 20 8 N.D. Report Staffing Status Report for the Air Force. 1 pg. 20 8 01/14/1969 Memo Copy of memo from John Ehrlichman to Bob Haldeman RE: Providing the Secret Service with the authorized list of those with White House passes and EOB passes. 1 pg. 20 8 01/14/1969 Letter Copy of letter from John Ehrlichman to Agent Al Wong RE: List of those who will be officing in the White House. 1 pg. 20 8 01/08/1969 Memo Memo from Ken Cole to John Ehrlichman RE: Bill Hopkins concern over proper arrangements for White House access for staff after the Inauguration. 1 pg. 20 8 N.D. Report White House Transition Procedures. 12 pgs. Tuesday, October 06, 2009 Page 1 of 9 Box Number Folder Number Document Date Document Type Document Description 20 8 N.D. Report White House Transition Procedures Appendix A. 8 pgs. 20 8 N.D. Report White House Transition Procedures Appendix B. 4 pgs. 20 8 N.D. Report White House Transition Procedures Appendix C. 1 pg. 20 8 N.D. Other Document Job description, pay grade and background profile for Dean Rusk, Secretary of State. 1 pg. 20 8 N.D. Other Document Pay grade and background profile for Harry W. Shlaudeman, Special Assistant. 1 pg. 20 8 N.D. Other Document Pay grade and background profile for Ernest K. -

THE MIDDLE Eash NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961-1963

THE JOHN F. KENNEDY NATIONAL SECURITY FILES THE MIDDLE EASh NATIONAL SECURITY FILES, 1961-1963 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of The John F. Kennedy National Security Files General Editor George C. Herring THE MIDDLE EAST National Security Files, 1961-1963 Microfilmed from the holdings of The John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Blair Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The John F. Kennedy national security files. The Middle East [microform]: national security files, 1961-1963. microfilm reels "Microfilmed from the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Massachusetts; project coordinator, Robert E. Lester." Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick. ISBN 1-55655-013-8 (microfilm) ISBN 1-55655-014-6 (printed guide) 1. Middle East-Politics and government-1945-1979-Sources. 2. Middle East-Foreign relations-United States-Sources. 3. United States-Foreign relations-Middle East-Sources. I. Lester, Robert. II. Hydrick, Blair. III. John F. Kennedy Library. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) [DS63.1.J65 1991] 327.73056-dc20 91-14019 CIP Copyright © 1987 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-014-6. TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction—The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: "Country Files," 1961-1963 v Introduction—The John F. Kennedy National Security Files: Middle East, 1961-1963 ix Scope and Content Note xiii Source Note xv Editorial Note xv Security Classifications xvii Key to Names xix Initialism List xxv Reel Index Reel 1 Afghanistan 1 Cyprus 12 India 17 Reel 2 India conl 24 Iran 29 Israel 49 Reels Israel cont 50 Saudi Arabia 73 United Arab Republic 79 Yemen 85 Author Index 87 Subject Index 91 GENERAL INTRODUCTION The John F.