City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue... Memoir Pieces by Oscar Firschein, Andy Grose Sandra Park

summer 2020 THE JOURNAL OF THE MASTER OF LIBERAL ARTS PROGRAM AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY in this issue... Memoir Pieces by Oscar Firschein, Andy Grose Sandra Park Poems by Amy McPhie Allebest, Sally Lindsay Honey, Prabhu Palani Essays by Michael Breger, Pete Dailey, Louisa Gillett, Christopher McBride, Mark A. Vander Ploeg, Astrid J. Smith PUBLISHING NOTES This publication features the works of students and alumni of the Master of Liberal Arts Program at Stanford University. Original Design Editors Suzanne West Candy Carter Teri Hessel Layout of Current Issue Jennifer Swanton Brown Jayne Pearce, Marketing, Master of Liberal Arts Program Reviewers Stanford Candy Carter Teri Hessel Carol Pearce Jennifer Swanton Brown Faculty Advisor Dr. Linda Paulson Rights and Permissions Copyrights for material included in this publication belong to their creators. In “The Female Hero and Cultural Conflict in Simin Daneshvar's Savushun,” the photograph is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons Wikiadabiat. In “Dark Arcady,” the photograph entitled “Sleeping Soldier” by Ernest Brooks is courtesy of the National Library of Scotland. In “Sestina,” the painting “Apollo and Daphne,” by John William Waterhouse (1908) is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. In “Liberating Mr Darcy,” the illustrations are from Pemberley.com at Wikimedia Commons. In “Towards a Musical Modernity,” the photograph is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. In “Prospero as Prince,” the engraving by Henry Fuseli (1797) is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, with credit to the Gertrude and Thomas Jefferson Mumford Collection, gift of Dorothy Quick Mayer, 1942. The remaining photos and illustrations are sourced from iStock. summer 2020 THE JOURNAL OF THE MASTER OF LIBERAL ARTS PROGRAM AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY in this issue.. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Volume 53, Issue 26 - Monday, May 14, 2018

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Summer 5-14-2018 Volume 53, Issue 26 - Monday, May 14, 2018 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 53, Issue 26 - Monday, May 14, 2018" (2018). The Rose Thorn Archive. 1216. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/1216 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROSE-HULMAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY • THEROSETHORN.COM • MONDAY, MAY 14, 2018 • VOLUME 53 • ISSUE 26 William Kemp, Hailey Hoover family members alike gathered in the SRC for the festivities. -

Jamal Rostami

CURRICULUM VITAE JAFAR KHADEMI HAMIDI, Ph.D. Mining Eng. Dept., Faculty of Engineering Phone: +98 21-82884364 Tarbiat Modares University Fax: +98 21-82884324 Jalal Ale Ahmad Highway, Nasr Bridge Email: [email protected] P.O. Box: 14115-143, Tehran, Iran http://www.modares.ac.ir/~jafarkhademi SUMMARY OF EXPERIENCE Jafar Khademi Hamidi received his PhD degree in Mining Engineering from Amirkabir University of Technology (Tehran Polytechnic) in January 2011 with dissertation entitled "A model for hard rock TBM performance prediction". As a PhD student in Tehran Polytechnic, he was a recipient of several competitive awards that include honored and top-rank recognition student, selected young researcher, sabbatical opportunity and INEF awards. He worked as a consultant in the area of underground construction, mechanical excavation, geotechnical investigations, construction bid preparation, tunneling in difficult ground conditions and longwall coal mine design between 2006 and 2013. He has started faculty job at Tarbiat Modares University (TMU) from spring 2012. Currently, as an Assistant Professor of Mining Engineering and founder of Mechanized Excavation Laboratory in TMU, he is to pursue basic and applied researches in the field of mechanical mining and excavation. RESEARCH INTEREST Underground mining (geotechnical engineering, design and planning, risk analysis) Mechanical mining and excavation (rock drillability/cuttability/boreability, design and fabrication of rock cuttability index tests, rock abrasion and tool wear) GIS -

Googoosh and Diasporic Nostalgia for the Pahlavi Modern

Popular Music (2017) Volume 36/2. © Cambridge University Press 2017, pp. 157–177 doi:10.1017/S0261143017000113 Iran’s daughter and mother Iran: Googoosh and diasporic nostalgia for the Pahlavi modern FARZANEH HEMMASI University of Toronto Faculty of Music, 80 Queen's Park, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C5, Canada E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article examines Googoosh, the reigning diva of Persian popular music, through an evaluation of diasporic Iranian discourse and artistic productions linking the vocalist to a feminized nation, its ‘victimisation’ in the revolution, and an attendant ‘nostalgia for the modern’ (Özyürek 2006) of pre-revolutionary Iran. Following analyses of diasporic media that project national drama and desire onto her persona, I then demonstrate how, since her departure from Iran in 2000, Googoosh has embraced her national metaphorization and produced new works that build on historical tropes link- ing nation, the erotic, and motherhood while capitalising on the nostalgia that surrounds her. A well-preserved blonde in her late fifties wearing a silvery-blue, décolletage-revealing dress looks deeply into the camera lens. A synthesised string section swells in the back- ground. Her carefully groomed brows furrow with pained emotion, her outstretched arms convey an exhausted supplication, and her voice almost breaks as she sings: Do not forget me I know that I am ruined You are hearing my cries IamIran,IamIran1 Since the 1979 establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iranian law has dictated that all women within the country’s borders must be veiled; women must also refrain from singing in public except under circumscribed conditions. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected]; -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Print to Air.Indd

[ABCDE] VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 F ro m P rin t to Air INSIDE TWP Launches The Format Special A Quiet Storm WTWP Clock Assignment: of Applause 8 9 13 Listen 20 November 21, 2006 © 2006 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program A Word about From Print to Air Lesson: The news media has the Individuals and U.S. media concerns are currently caught responsibility to provide citizens up with the latest means of communication — iPods, with information. The articles podcasts, MySpace and Facebook. Activities in this guide and activities in this guide assist focus on an early means of media communication — radio. students in answering the following Streaming, podcasting and satellite technology have kept questions. In what ways does radio a viable medium in contemporary society. providing news through print, broadcast and the Internet help The news peg for this guide is the establishment of citizens to be self-governing, better WTWP radio station by The Washington Post Company informed and engaged in the issues and Bonneville International. We include a wide array and events of their communities? of other stations and media that are engaged in utilizing In what ways is radio an important First Amendment guarantees of a free press. Radio is also means of conveying information to an important means of conveying information to citizens individuals in countries around the in widespread areas of the world. In the pages of The world? Washington Post we learn of the latest developments in technology, media personalities and the significance of radio Level: Mid to high in transmitting information and serving different audiences. -

Mário Pedrosa PRIMARY DOCUMENTS

Mário Pedrosa PRIMARY DOCUMENTS Editors Glória Ferreira and Paulo Herkenhoff Translation Stephen Berg Date 2015 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Purchase URL https://store.moma.org/books/books/mário-pedrosa-primary-documents/911- 911.html MoMA’s Primary Documents publication series is a preeminent resource for researchers and students of global art history. With each volume devoted to a particular critic, country or region outside North America or Western Europe during a delimited historical period, these anthologies offer archival sources–– such as manifestos, artists’ writings, correspondence, and criticism––in English translation, often for the first time. Newly commissioned contextual essays by experts in the field make these materials accessible to non-specialist readers, thereby providing the critical tools needed for building a geographically inclusive understanding of modern art and its histories. Some of the volumes in the Primary Documents series are now available online, free-of-charge. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art 2 \ Mário Pedrosa Primary Documents Edited by Glória Ferreira and Paulo Herkenhoff Translation by Stephen Berg The Museum of Modern Art, New York Leadership support for Mário Pedrosa: Copyright credits for certain illustrations Primary Documents was provided and texts are cited on p. 463. by The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art. Distributed by Duke University Press, Durham, N.C. (www.dukepress.edu) Library of Congress Control Number: 2015954365 This publication was made possible ISBN: 978-0-87070-911-1 with cooperation from the Fundação Roberto Marinho. Cover: Mário Pedrosa, Rio de Janeiro. c. 1958 p. 1: Mário Pedrosa in front of a sculp- Major support was provided by the ture by Frans Krajcberg at the artist’s Ministério da Cultura do Brasil. -

Cinematic Modernity Cosmopolitan Imaginaries in Twentieth Century Iran

Cinematic Modernity Cosmopolitan Imaginaries in Twentieth Century Iran by Golbarg Rekabtalaei A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Golbarg Rekabtalaei 2015 Cinematic Modernity Cosmopolitan Imaginaries in Twentieth Century Iran Golbarg Rekabtalaei Doctor of Philosophy Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2015 Abstract Cinematic Modernity explores the ―genesis amnesia‖ that informs the conventional scholarly accounts of Iranian cinema history. Critiquing a ―homogeneous historical time,‖ this dissertation investigates cinematic temporality autonomous from (and in relation to) political and social temporalities in modern Iran. Grounding the emergence of cinema in Iran within a previously neglected cosmopolitan urban social formation, it demonstrates how the intermingling of diverse Russian, Georgian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, French and British communities in interwar Tehran, facilitated the formation of a cosmopolitan cinematic culture in the early twentieth century. In the 1930s, such globally-informed and aspiring citizens took part in the making of a cinema that was simultaneously cosmopolitan and Persian-national, i.e. cosmo-national. This dissertation explains how in the late 1940s, after a decade long hiatus in Iranian feature-film productions—when cinemas were dominated by Russian, British, and German films—Iranian filmmakers and critics actualised their aspirations for a sovereign national cinema in the form a sustained commercial industry; this cinema staged the moral compromises of everyday life and negotiation of conflicting allegiances to families and social networks in a rapidly changing Iran—albeit in entertaining forms. While critiqued for ―imitating‖ European commercial films, this cinema—known as ―Film-Farsi‖ (Persian-Language)–was highly ii informed by lived experiences of Iranians and international commercial motion pictures. -

Abstracts Electronic Edition

Societas Iranologica Europaea Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the State Hermitage Museum Russian Academy of Sciences Abstracts Electronic Edition Saint-Petersburg 2015 http://ecis8.orientalstudies.ru/ Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts CONTENTS 1. Abstracts alphabeticized by author(s) 3 A 3 B 12 C 20 D 26 E 28 F 30 G 33 H 40 I 45 J 48 K 50 L 64 M 68 N 84 O 87 P 89 R 95 S 103 T 115 V 120 W 125 Y 126 Z 130 2. Descriptions of special panels 134 3. Grouping according to timeframe, field, geographical region and special panels 138 Old Iranian 138 Middle Iranian 139 Classical Middle Ages 141 Pre-modern and Modern Periods 144 Contemporary Studies 146 Special panels 147 4. List of participants of the conference 150 2 Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts Javad Abbasi Saint-Petersburg from the Perspective of Iranian Itineraries in 19th century Iran and Russia had critical and challenging relations in 19th century, well known by war, occupation and interfere from Russian side. Meantime 19th century was the era of Iranian’s involvement in European modernism and their curiosity for exploring new world. Consequently many Iranians, as official agents or explorers, traveled to Europe and Russia, including San Petersburg. Writing their itineraries, these travelers left behind a wealthy literature about their observations and considerations. San Petersburg, as the capital city of Russian Empire and also as a desirable station for travelers, was one of the most important destination for these itinerary writers. The focus of present paper is on the descriptions of these travelers about the features of San Petersburg in a comparative perspective. -

Read the Introduction

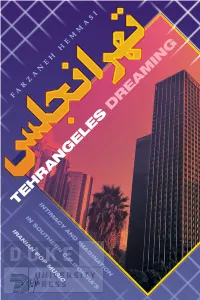

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try.