Dark Lonerism: Self-Sabotage, Apathy, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 53, Issue 26 - Monday, May 14, 2018

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Summer 5-14-2018 Volume 53, Issue 26 - Monday, May 14, 2018 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 53, Issue 26 - Monday, May 14, 2018" (2018). The Rose Thorn Archive. 1216. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/1216 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROSE-HULMAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY • THEROSETHORN.COM • MONDAY, MAY 14, 2018 • VOLUME 53 • ISSUE 26 William Kemp, Hailey Hoover family members alike gathered in the SRC for the festivities. -

The Conflict Between Liberty of Conscience and Church Authority

Reformed Theological Seminary THE CONFLICT BETWEEN LIBERTY OF CONSCIENCE AND CHURCH AUTHORITY IN TODAY’S EVANGELICAL CHURCH An Integrated Thesis Submitted to Dr. Donald Fortson In Candidacy for the Degree Of Master of Arts By Gregory W. Perry July 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………. iii 1. The Conflict between Liberty of Conscience and Church Authority Introduction…………………………………………………………………… 1 The Power Struggle…………………………………………………………… 6 2. The Bible on Liberty of Conscience and Church Authority The Liberty of the Conscience in Its Proper Place……………………………. 14 Church Authority: The Obligation to Obedience……………………………... 30 The Scope of Church Authority………………………………………………. 40 Church Discipline: The Practical Application of Church Authority………….. 54 3. The History of Liberty of Conscience and Church Authority The Reformed Conscience……………………………………………………. 69 The Puritan Conscience………………………………………………………. 81 The Evolution of the American Conscience………………………………….. 95 4. Application for Today The State of the Church Today………………………………………………. 110 The Purpose-Driven Conscience…………………………………………….. 117 Feeding the Fear of Church Authority……………………………………….. 127 Practical Implications………………………………………………………… 139 Selected Bibliography………………………………………………………………... 153 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Reverend P.G. Mathew and the elders of Grace Valley Christian Center in Davis, California for their inspiration behind this thesis topic. The first way they inspired this thesis is through their faithful preaching of God’s Word, right administration of the sacraments, and their uncompromising resolve to exercise biblical discipline. Their godly example of faithfulness in leading their flock in the manner that the Scriptures require was the best resource in formulating these ideas. The second inspiration was particularly a set of sermons that Pastor Mathew preached on Libertinism from March 28-May 2, 2004. -

Examensuppsats På Kandidatnivå Nedskalad Truminspelning Med Ett Stort Sound

! Examensuppsats på kandidatnivå Nedskalad truminspelning med ett stort sound Om Kevin Parker och hans sätt att producera trummor Författare: Andreas Troedsson Handledare: Berk Sirman Seminarieexaminator: Thomas Von Wachenfeldt Formell kursexaminator: Thomas Florén Ämne/huvudområde: Ljud- och musikproduktion Kurskod: LP2005 Ljudproduktion, fördjupningskurs Poäng: 30 hp Examinationsdatum: 2017-01-13 Jag/vi medger publicering i fulltext (fritt tillgänglig på nätet, open access): Ja Abstract Producenten Kevin Parker har onekligen fått igenkänning för sitt trumsound. Som huvudsaklig låtskrivare och producent i rockbandet Tame Impala har han skapat sig ett ”signature sound”. Eftersom många gillar hur Parkers trummor låter har det förts långa diskussioner angående produktionsprocessen. Uppsatsen ämnade att ta reda på hur Parkers produktion sett ut och vilka ljudliga artefakter det är som utgör hans sound. Resultatet visar på en väldigt nedskalad inspelning. Ofta med ett enkelt vintage-trumkit och tre till fyra mikrofoner, dämpade skinn samt en hel del kompression och distorsion. Soundet kan beskrivas som väldigt energiskt, mycket tack vare just hård kompression och distorsion. Parkers sound känns igen även utanför Tame Impala. Trummorna upplevs i många fall som mycket mer än bara ett rytminstrument. Uppsatsen förklarar hur okonventionella produktionsprocesser kan ge upphov till originella ljudliga karaktärer, vilket i slutändan kan anses en positiv konsekvens. Keywords Kevin Parker, Tame Impala, producent, inspelning, trummor, musikanalys. Innehållsförteckning -

Psychology As Religion: the Cult of Self- Worship Pdf, Epub, Ebook

PSYCHOLOGY AS RELIGION: THE CULT OF SELF- WORSHIP PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul C. Vitz | 191 pages | 07 Mar 1995 | William B Eerdmans Publishing Co | 9780802807250 | English | Grand Rapids, United States Psychology as Religion: The Cult of Self-Worship PDF Book All is written in sand by a self in flux. Really quite profound and enlightening, shedding much light on the all-present self culture of modern life. He begins by giving the reader a brief biography on the fathers of the modern psychology movement along with some of their theories. A classic look at self-esteem and its proponents. He was a Christian and was disturbed about the growing narcissism and other issues escalating in American society as the theories of self-actualization and related "selfist" ideas gained popularity in modern counseling, public education, media and even religion. He gives the credit to our educational system for the transformation of our society into a culture of pure selfism. Please Register or Login to post new comment. Open Preview See a Problem? Welcome back. I understood the need for the first half as I read the rest of the book. Sort order. Rogers and May both went to Union Theological Seminary and broke from their Christian upbringing after traveling to Europe. Return to Book Page. Dec 11, Emily Duffey rated it really liked it. The opening chapter was dry reading but I suppose necessary as a historical backdrop. On Creativity and the Unconscious brings together Freud's important essays on the many expressions of creativity—including art, literature, love, dreams, and spirituality. -

Tales of Dread

Zlom1_2019_Sestava 1 5.4.19 8:01 Stránka 65 WINNER OF THE FABIAN DORSCH ESA ESSAY PRIZE TALES OF DREAD MARK WINDSOR ‘Tales of dread’ is a genre that has received scant attention in aesthetics. In this paper, I aim to elaborate an account of tales of dread which (1) effectively distinguishes these from horror stories, and (2) helps explain the close affinity between the two, accommodating borderline cases. I briefly consider two existing accounts of the genre – namely, those of Noël Carroll and of Cynthia Freeland – and show why they are inadequate for my purposes. I then develop my own account of tales of dread, drawing on two theoretical resources: Freud’s ‘The “Uncanny”’, and Tzvetan Todorov’s The Fantastic. In particular, I draw on Freud to help distinguish tales of dread from horror stories, and I draw on Todorov to help explain the fluidity between the genres. I argue that both horror stories and tales of dread feature apparent impossibilities which are threatening; but whereas in horror stories the existence of the monster (the apparent impossibility) is confirmed, tales of dread are sustained by the audience’s uncertainty pertaining to preternatural objects or events. Where horror monsters pose an immediate, concrete danger to the subject’s physical well-being, these preternatural objects or events pose a psychological threat to the subject’s grasp of reality. I In his book The Philosophy of Horror, Noël Carroll identifies a narrative genre that he calls ‘tales of dread’. Unlike horror stories, Carroll claims, tales of dread do not feature monstrous entities or beings, but rather a distinctive kind of preternatural event. -

Staging New Materialism, Posthumanism and the Ecocritical Crisis in Contemporary Performance

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Acting Objects: Staging New Materialism, Posthumanism and the Ecocritical Crisis in Contemporary Performance Sarah Lucie The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3828 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ACTING OBJECTS STAGING NEW MATERIALISM, POSTHUMANISM AND THE ECOCRITICAL CRISIS IN CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE by SARAH LUCIE A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre and Performance in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 SARAH LUCIE All rights reserved ii Acting Objects: Staging New Materialism, Posthumanism and the Ecocritical Crisis in Contemporary Performance by Sarah Lucie This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Theatre and Performance in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________________________________________________________________________ Date Peter Eckersall Chair of Examining Committee __________________________________________________________________________ Date Peter Eckersall Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Erika Lin Edward Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Acting Objects: Staging New Materialism, Posthumanism and the Ecocritical Crisis in Contemporary Performance by Sarah Lucie Advisor: Peter Eckersall I investigate the material relationship between human and nonhuman objects in performance, asking what their shifting relations reveal about our contemporary condition. -

Neopastoral Artifacts and the Phenomenology of Environment in American Modernist Poetics

REFUSE TO RELIC: NEOPASTORAL ARTIFACTS AND THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF ENVIRONMENT IN AMERICAN MODERNIST POETICS Douglas ii Refuse to Relic: Neopastoral Artifacts and the Phenomenology of Environment in American Modernist Poetics Thesis format: Monograph by Jeffrey Daniel Douglas, B.A., B.Ed., M.A. Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate Studies McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario, Canada © Jeffrey D. Douglas 2013 Douglas iii Abstract Building on concepts of the pastoral, the picturesque, the “vernacular ruin,” and frontierism in an American context, this thesis explores the interest in ruin and commodity- oriented refuse within rural, wilderness, and what Leo Marx in The Machine in the Garden calls “middle ground” environments. Chapter one analyzes how “nature,” as both scenery and the natural environment removed from civilization, has been conceptualized as a place where human-made objects become repurposed through the gaze of the spectator. Theories surrounding gallery and exhibition space, as well as archaeological practices related to garbage excavation, are assessed to determine how waste objects, when wrested out of context, become artifacts of cultural significance. Chapter two turns to focus on the settler experience of the frontier in order to locate a uniquely American evolution of the interest in everyday waste objects. Because the frontier wilderness in American culture can be regarded as a site of transition and malleability, it is argued that the (mis)perception of object matter within this transitional space helped to shape modernist poetics and its association with everyday objects. Chapters three and four return to the rural and the pastoral to focus on Marx’s concept of the “middle ground,” borderlands of quasi-natural space that are located “somewhere ‘between,’ yet in a transcendent relation to, the opposing forces of civilization and nature” (23). -

Enneagram-Type-2.Pdf

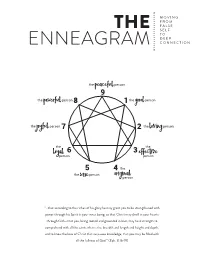

M O V I N G F R O M F A L S E THE S E L F T O D E E P ENNEAGRAM CONNECTION the PEACEFUL person 9 the POWERFUL person 8 1 the GOOD person the JOYFUL person 7 2 the LOVING person the 6 3 the LOYAL person EFFECTIVE person 5 4 the the person WISE ORIGINAL person “…that according to the riches of his glory he may grant you to be strengthened with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith—that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have strength to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with all the fullness of God.” (Eph. 3:16-19) In the early hours of April 15, 1912, on its maiden voyage from South Hampton to New York City, the Titanic sank when it collided “... THAT ACCORDING TO THE RICHES with an iceberg in the cold waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. OF HIS GLORY HE MAY GRANT Tragically, more than 1,500 people lost their lives. At the time, YOU TO BE STRENGTHENED WITH the Titanic was the largest, most well-built and luxurious ship ever POWER THROUGH HIS SPIRIT IN conceived. It was thought to be unsinkable. As one crew member YOUR INNER BEING ... TO KNOW THE reportedly said, “Not even God himself could sink this ship.” But LOVE OF CHRIST THAT SURPASSES what those aboard the Titanic didn’t know was that hidden beneath KNOWLEDGE .. -

Mário Pedrosa PRIMARY DOCUMENTS

Mário Pedrosa PRIMARY DOCUMENTS Editors Glória Ferreira and Paulo Herkenhoff Translation Stephen Berg Date 2015 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Purchase URL https://store.moma.org/books/books/mário-pedrosa-primary-documents/911- 911.html MoMA’s Primary Documents publication series is a preeminent resource for researchers and students of global art history. With each volume devoted to a particular critic, country or region outside North America or Western Europe during a delimited historical period, these anthologies offer archival sources–– such as manifestos, artists’ writings, correspondence, and criticism––in English translation, often for the first time. Newly commissioned contextual essays by experts in the field make these materials accessible to non-specialist readers, thereby providing the critical tools needed for building a geographically inclusive understanding of modern art and its histories. Some of the volumes in the Primary Documents series are now available online, free-of-charge. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art 2 \ Mário Pedrosa Primary Documents Edited by Glória Ferreira and Paulo Herkenhoff Translation by Stephen Berg The Museum of Modern Art, New York Leadership support for Mário Pedrosa: Copyright credits for certain illustrations Primary Documents was provided and texts are cited on p. 463. by The International Council of The Museum of Modern Art. Distributed by Duke University Press, Durham, N.C. (www.dukepress.edu) Library of Congress Control Number: 2015954365 This publication was made possible ISBN: 978-0-87070-911-1 with cooperation from the Fundação Roberto Marinho. Cover: Mário Pedrosa, Rio de Janeiro. c. 1958 p. 1: Mário Pedrosa in front of a sculp- Major support was provided by the ture by Frans Krajcberg at the artist’s Ministério da Cultura do Brasil. -

Philosophy for Children and Pragmatism Part I. the Uncanny History of Pragmatism

Philosophy for Children and Pragmatism Part I. The Uncanny History of Pragmatism Agora Philosophical Forum Handout by Soroush Marouzi 1. A Brief Overview of the Pragmatism-P4C Relation: - Pragmatism was born in 1867 in America - P4C as a social movement was initiated in the early 1970’s - Pragmatism, as a philosophical position, manifests itself in the educational method advocated by the proponents of the P4C movement - Hence, we shall start with an overview of pragmatism - The methodological sensitivities to explore pragmatist philosophies o Employing the intellectual biography approach to unfold the varieties of pragmatist notions 2. The Metaphysical Club: - The American pragmatists were struggling to build the ‘modern’ America after the Civil war. o A historical narrative of the club by Louis Menand (2001) - The objective of the club: Bring metaphysics down to earth; start with human experience - The Four Greats: Charles S. Peirce, William James, Oliver W. Holmes, and Chauncy Wright 2.1. Charles. S. Peirce (1839-1914): - Peirce was “the greatest American thinker ever” (Russell 1959, p 276). - Peirce invented pragmatism o Along with semiotics, mathematical logic, statistical economics, game-theoretic semantics, economics of science, propensity interpretation of probability, indeterministic metaphysics, falsification, abductive reasoning, etc. - Peirce’s works to be discussed in this workshop o On a New List of Categories (1867) o The Fixation of Belief (1877) o How to Make Our Ideas Clear (1878) 2.2. William James (1842-1910): - A charming man with a popular philosophy - He is known as the father of psychology in America. o In his Principles of Psychology (1890), he demarcated psychology from philosophy. -

Residents Cope with Uneven Temperatures Sor, Said It Should Not Be Too Much of a Wor- Ry for Those Running Because It Is Only a Mile

Eastern Illinois University The Keep January 2014 1-24-2014 Daily Eastern News: January 24, 2014 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2014_jan Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: January 24, 2014" (2014). January. 9. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2014_jan/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2014 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in January by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOURNING IN MARTIN ALL THE RIGHT NOTES Eastern fails to outscore the Eastern’s percussion group follow Tennessee-Martin Skyhawks in their passions of music. Thursday’s game. Page 3 Page 8 WWW.DAILYEASTERNNEWS.COM HE DT ailyEastErnnEws Friday, Jan. 24, 2014 “TELL THE TRUTH AND DON’T BE AFRAID” VOL. 98 | NO. 86 Inclement weather should not stop runners By Jarad Jarmon Associate News Editor | @JJarmonReporter Stripping their clothes off piece-by-piece, students will be running through the frigid temperatures expected for the Nearly Naked Mile at 10 a.m. Saturday starting in the Car- man Hall parking lot. Roughing it through 20 mile per hour winds and temperatures below freezing, 30 registered runners, with more expected to join by the time the race starts, will be stripping down to their “bathing suit area” and running a mile. There will be 3-4 stations along the trail where runners will take off specific items. For instance, at the first station, they will take off mittens, hats and scarfs they may have on. -

ARIA TOP 100 ALBUMS CHART 2007 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 100 ALBUMS CHART 2007 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 CALL ME IRRESPONSIBLE Michael Buble <P>4 WMA 9362499111 2 I'M NOT DEAD P!nk <P>8 LAF/SBME 88697075172 3 FUTURE SEX/LOVE SOUNDS Justin Timberlake <P>4 JVE/SBME 82876880622 4 ON A CLEAR NIGHT Missy Higgins <P>3 ELEV/UMA ELEVENCD70 5 THE DUTCHESS Fergie <P>3 A&M/UMA 1707562 6 DREAM DAYS AT THE HOTEL EXISTENCE Powderfinger <P>3 UMA 1735251 7 GRAND NATIONAL The John Butler Trio <P>3 JAR/MGM JBT011 8 LONG ROAD OUT OF EDEN Eagles <P>2 UMA 1749402 9 YOUNG MODERN Silverchair <P>3 ELEV/EMI ELEVENCD63 10 TIMBALAND PRESENTS: SHOCK VALUE Timbaland <P>2 INR/UMA 1726605 11 EXILE ON MAINSTREAM Matchbox Twenty <P>2 WMA 7567899698 12 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT Linkin Park <P>2 WARNER 9362444772 13 DELTA Delta Goodrem <P>2 SBM 88697193922 14 INFINITY ON HIGH Fall Out Boy <P>2 ISL/UMA 1720575 15 SNEAKY SOUND SYSTEM Sneaky Sound System <P>2 MGM WHACK04 16 EYES OPEN Snow Patrol <P>4 UMA 9853178 17 THE TRAVELING WILBURYS COLLECTION The Traveling Wilburys <P>2 RHI/WAR 8122799824 18 LIFE IN CARTOON MOTION Mika <P>2 MER/UMA 1723781 19 THE BEST DAMN THING Avril Lavigne <P>2 RCA/RCR 88697037742 20 ECHOES, SILENCE, PATIENCE & GRACE Foo Fighters <P> RCA/SBME 88697301242 21 THE SWEET ESCAPE Gwen Stefani <P>2 INR/UMA 1717390 22 THE MEMPHIS ALBUM Guy Sebastian <P> SBMG/SBM 88697196012 23 GOOD MORNING REVIVAL Good Charlotte <P> EPI/SBME 88697069352 24 EXTREME BEHAVIOR Hinder <P> UMA 9884987 25 LOOSE Nelly Furtado