“Me”: the Nature of Conceit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inferiority Complex

www.bsmi.org INFERIORITY COMPLEX Prevention in Children and Relief from It in Adults Timothy Lin, Ph.D. Everyone starts life with some feelings of inferiority. Subsequent success or failure is determined by the ability to adjust the inferiority feeling to the demands of life. Normal development requires the recognition of one’s limitations and capacities in order to achieve a profitable balance in emotional maturity. The inferiority complex is different from the inferior feeling of which the former is the master but the latter can become a servant to the individual. As a master, the complex may cause a person to have ultimate failure and maladjustment; as a servant, the feeling may produce success in achieving valuable goals in life. No one succeeds without some inferior feeling and almost everyone who fails does so because of an inferiority complex. We will see the serious nature of an inferiority complex by considering the nature, the manifestations, and the cure. Nature The nature of the inferiority complex includes definition, distinction from the superiority complex, and causes. Inferiority complex may be defined as: An abnormal or pathological state which, due to the tendency of the complex to draw unrelated ideas into itself, leads the individual to depreciate himself, to become unduly sensitive, to be too eager for praise and flattery, and to adopt a derogatory attitude toward others.1 This definition is the basis of the following discussion. How to Distinguish from a Superiority Complex: The genuine superiority complex is not superficial conceit but the consciousness of superiority developed from the feeling of personal cleverness, ability superior to their peers, and easy accomplishment of difficult tasks. -

THE INFLATED SELF the INFLATED SELF Human Illusions and the Biblical Call to Hope

THE INFLATED SELF THE INFLATED SELF Human Illusions and the Biblical Call to Hope DAVID G. MYERS The Seabury Press * New York 1981 The Seabury Press 815 Second Avenue New York, N.Y. 10017 Copyright © 1980 by David G. Myers All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, storedin a retrieval system, or transmitted, in anyform or by anymeans, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of The Seabury Press. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalogingin Publication Data Myers, David G The inflated self. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Good and evil. 2. Beliefand doubt. 3. Hope. I. Title. BJ1401.M86 24r.3 80-16427 ISBN: 0-8I64-2326-I Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following publishers for per mission to use the materials listed: American Psychological Association for a chart excerpted from "Meta- Analysis of Psychotherapy Outcome Studies," by Mary Lee Smith and Gene V. Glass which appeared in volume 32 of the American Psychologist. Faber and Faber Ltd for excerpts from "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" and "The Hollow Men" in Collected Poems 1909-1962 byT. S. Eliot. Harcourt BraceJovanovich, Inc. for excerptsfrom "The LoveSongof J. AlfredPrufrock" in Collected Poems 1909-1962 byT. S. Eliot, and for excerpts from the "The Hollow Men" in Collected Poems 1909- 1962 by T. S. Eliot, copyright 1936by Harcourt BraceJovanovich, Inc.; copyright 1963, 1964 by T. S. Eliot. Three Rivers PoetryJournal for the poem "The Healers" by Jack Ridl. To my parents Kenneth Gordon Myers Luella Nelson Myers Lord, I have given up my pride and turned away from my arrogance. -

Dunning–Kruger Effect - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Dunning–Kruger effect - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunning–Kruger_effect Dunning–Kruger effect From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias in which unskilled individuals suffer from illusory superiority, mistakenly rating their ability much higher than average. This bias is attributed to a metacognitive inability of the unskilled to recognize their mistakes.[1] Actual competence may weaken self-confidence, as competent individuals may falsely assume that others have an equivalent understanding. David Dunning and Justin Kruger of Cornell University conclude, "the miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others".[2] Contents 1 Proposal 2 Supporting studies 3 Awards 4 Historical references 5 See also 6 References Proposal The phenomenon was first tested in a series of experiments published in 1999 by David Dunning and Justin Kruger of the Department of Psychology, Cornell University.[2][3] They noted earlier studies suggesting that ignorance of standards of performance is behind a great deal of incompetence. This pattern was seen in studies of skills as diverse as reading comprehension, operating a motor vehicle, and playing chess or tennis. Dunning and Kruger proposed that, for a given skill, incompetent people will: 1. tend to overestimate their own level of skill; 2. fail to recognize genuine skill in others; 3. fail to recognize the extremity of their inadequacy; 4. recognize and acknowledge their own previous lack of skill, if they are exposed to training for that skill. Dunning has since drawn an analogy ("the anosognosia of everyday life")[1][4] with a condition in which a person who suffers a physical disability because of brain injury seems unaware of or denies the existence of the disability, even for dramatic impairments such as blindness or paralysis. -

Psychodynamics of Narcissism—A Psychological Approach

Psychodynamics of Narcissism—A Psychological Approach Roohi Research Scholar in English Dept of HSS, Andhra University College of Engineering Andhra University Visakhapatnam India Abstract: Loving yourself is not a sin, but being obsessed with one‟s own happiness and letting others to suffer is „Narcissism‟. This disease is unique as the one who is suffering from narcissism may not realize that he is a „Narcissist‟ and in some cases a narcissist fails to cure his disease as he refuses to understand the suffering caused by him to others. A narcissist is dangerous to himself and the society. He can be cured if he discovers of what he is suffering with and realizes that only he can heal himself .i.e. „Narcissists are the cure to their own poison‟. Keywords: Character disorder, ego-strengthening, Ego State Therapy, false self, hypnosis, hypnotic age progression, narcissism, personality Introduction: The word „Narcissism‟ originated from Greek mythology, where the handsome young king „Narcissus‟ fell in love with his own image reflected in a pool of water. Narcissism is a strange disease, it is visible to others but veiled to the deceased, a person suffering from narcissism is a threat to himself and the society. It is a psychological problem which needs attention and prevention. Except in the sense of primary narcissism or healthy self-love, narcissism is usually www.ijellh.com 156 considered as a problem in a person's or group's relationships with self and others. Narcissism is not the same as egocentrism. According to K.W. Campbell and J.D Foster in an article published in PA: Psychology Press. -

Diversion Tactics

Diversion Tactics U N D E R S T A N D I N G M A L A D A P T I V E B E H A V I O R S I N R E L A T I O N S H I P S Toxic people often engage in maladaptive behaviors in relationships that ultimately exploit, demean and hurt their intimate partners, family members and friends. They use a plethora of diversionary tactics that distort the reality of their victims and deflect responsibility. Abusive people may employ these tactics to an excessive extent in an effort to escape accountability for their actions. Here are 20 diversionary tactics toxic people use to silence and degrade you. 1 Diversion Tactics G A S L I G H T I N G Gaslighting is a manipulative tactic that can be described in different variations three words: “That didn’t happen,” “You imagined it,” and “Are you crazy?” Gaslighting is perhaps one of the most insidious manipulative tactics out there because it works to distort and erode your sense of reality; it eats away at your ability to trust yourself and inevitably disables you from feeling justified in calling out abuse and mistreatment. When someone gaslights you, you may be prone to gaslighting yourself as a way to reconcile the cognitive dissonance that might arise. Two conflicting beliefs battle it out: is this person right or can I trust what I experienced? A manipulative person will convince you that the former is an inevitable truth while the latter is a sign of dysfunction on your end. -

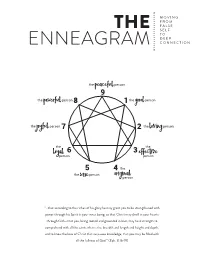

Enneagram-Type-2.Pdf

M O V I N G F R O M F A L S E THE S E L F T O D E E P ENNEAGRAM CONNECTION the PEACEFUL person 9 the POWERFUL person 8 1 the GOOD person the JOYFUL person 7 2 the LOVING person the 6 3 the LOYAL person EFFECTIVE person 5 4 the the person WISE ORIGINAL person “…that according to the riches of his glory he may grant you to be strengthened with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith—that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have strength to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with all the fullness of God.” (Eph. 3:16-19) In the early hours of April 15, 1912, on its maiden voyage from South Hampton to New York City, the Titanic sank when it collided “... THAT ACCORDING TO THE RICHES with an iceberg in the cold waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. OF HIS GLORY HE MAY GRANT Tragically, more than 1,500 people lost their lives. At the time, YOU TO BE STRENGTHENED WITH the Titanic was the largest, most well-built and luxurious ship ever POWER THROUGH HIS SPIRIT IN conceived. It was thought to be unsinkable. As one crew member YOUR INNER BEING ... TO KNOW THE reportedly said, “Not even God himself could sink this ship.” But LOVE OF CHRIST THAT SURPASSES what those aboard the Titanic didn’t know was that hidden beneath KNOWLEDGE .. -

PERSONALITY CHALLENGES and the IMPACT on CHILD CUSTODY DISPUTES Mark Lovinger, Ph.D., MSCP Melissa Seagro LISW-S

4/6/21 PERSONALITY CHALLENGES AND THE IMPACT ON CHILD CUSTODY DISPUTES Mark Lovinger, Ph.D., MSCP Melissa Seagro LISW-S ASSOCIATION OF FAMILY AND CONCILIATION COURTS OHIO CHAPTER ANNUAL CONFERENCE APRIL 7, 2021 1 SESSION OVERVIEW • Overview of the three clusters of personality disorders, their similarities, which clusters are typically observed in high contentious child custody cases • Identify five personality disorders typically seen in contentious child custody cases and how these disturbances can impact litigant’s ability to negotiate parenting plans • Analyze strategies that can be used to engage litigants who portray traits/features of a personality disturbance 2 1 4/6/21 Disclaimer • Attending this seminar shall not be construed as permission to diagnose personality disorders. • Should you believe someone has a personality disorder, it is best to keep it to yourself and not disclose your thoughts directly to the individual. 3 The Basics • Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Ed. defines a personality traits as “…enduring patters of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and oneself that are exhibited in a wide range of social and personal contexts.” (pg. 647) • Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Ed. defines a personality disorder as “…an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment.” (pg. 645) There are a total of 10 personality disorders. • Personality traits that are inflexible, maladaptive, significant functional impairment/subjective stress, cannot be better accounted for as a medical diagnosis (ex. -

The “Hero Syndrome”

The Hero Syndrome 1 THE “HERO SYNDROME” Sergeant Ben D. Cross Arkansas State Police School of Law Enforcement Supervision Session XLIII November 1, 2014 The Hero Syndrome 2 INTRODUCTION Hero, a word we all associate with accolades of praise upon an individual who has done a selfless or exemplary act. A word defined by dictionary standards as: A person noted for feats of courage or nobility of purpose, especially one who has risked or sacrificed his or her life. (The American Heritage College Dictionary, Third Edition) Syndrome, a word we usually associate with a negative connotation, almost as if it were a contagious disease. A word defined by dictionary standards as: A group of symptoms that collectively indicate or characterize a disease or another abnormal condition. A complex of symptoms indicating the existence of an undesirable condition or quality. A distinctive or characteristic pattern of behavior. (The American Heritage College Dictionary, Third Edition) The pairing of these two words to describe a condition known in the main stream media as “The Hero Syndrome” brings rise to a variety of pre-conceived notions as to the origins, facts, myths, and ultimately, the reality of what this disorder encompasses. This paper will delve into the history, current trends, investigative practices, (or lack thereof), and the detriment to the law enforcement profession when occurrences of this nature come to light. I hope to also bring stark awareness to law enforcement managers who “look the other way” and do not readily and aggressively deal with this problem head on. BACKGROUND The so called Hero Syndrome is not actually a syndrome at all. -

We Value Humility) Pastor Dave Lomas, Reality San Francisco

Sermon Transcript from October 16th, 2016 God Is God and I’m Not (We Value Humility) Pastor Dave Lomas, Reality San Francisco We are in a series now on our vision statement. So, we're in a vision and values series that we started last week. Here's the vision of our church. If you are new to our church, if you've not been to Welcome to Reality or if you have been a part of this church but don't know it yet, here it is. Our vision statement, it's on our website and we communicate this all sorts of ways when we do events. It's like the grid that we see everything through as a church. Here it is. The first part of this has been our vision from the very beginning, since before the church was even started. This was the vision. Then, we added the second part of it just a couple years into the church. It's this: "We are a community following Jesus, seeking renewal in our city." A community following Jesus, seeking renewal in our city. I love that. I love the simplicity of it. I also think it's very profound as well. I hope that you would commit it to memory. A few years ago, we wanted to know what it would feel like in the culture of our church, in our lives, like felt experience or collective experience of what it would feel like to live into this vision. What would it be if that's the vision? We say that. -

December 15, 2008 Perspectives in Theory

December 15, 2008 Perspectives in Theory: Anthology of Theorists affecting the Educational World Editors: Misty M. Bicking, Brian Collins, Laura Fernett, Barbara Taylor, Kathleen Sutton Shepherd University Table Of Contents Abstract_______________________________________________________________________4 Alfred Adler ___________________________________________________________________5 Melissa Bartlett Mary Ainsworth _______________________________________________________________17 Misty Bicking Alois Alzheimer _______________________________________________________________30 Maura Bird Albert Bandura ________________________________________________________________45 Lauren Boyer James A. Banks________________________________________________________________59 Adel D. Broadwater Vladimir Bekhterev_____________________________________________________________72 Thomas Cochrane Benjamin Bloom_______________________________________________________________86 Brian Collins John Bowlby and Attachment Theory ______________________________________________98 Colin Curry Louis Braille: Research_________________________________________________________111 Justin Everhart Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model___________________________________________124 Kristin Ezzell Jerome Bruner________________________________________________________________138 Laura Beth Fernett Noam Chomsky Stubborn Without________________________________________________149 Jamin Gibson Auguste Comte _______________________________________________________________162 Heather Manning -

Validation of Adlerian Inferiority (Compin) and Superiority (Sucomp) Complex Shortened Scales

CIVITAS, 2017, 7(2), 13-35 www.civitas.rs Đorđe Čekrlija1 doi: 10.5937/Civitas1701013C Dijana Đurić2 UDC 159.923 Biljana Mirković3 316.37 Original scientifc paper Received: 30.05.2017. Accepted: 25.07.2017. VALIDATION OF ADLERIAN INFERIORITY (COMPIN) AND SUPERIORITY (SUCOMP) COMPLEX SHORTENED SCALES Abstract: Te main purpose of this study is to examine the inferiority and superiority complex scales, and develop their shortened versions. For this purpose two studies were conducted. In the frst study, 395 stu- dents (62% female) were tested, and the inferiority (COMPIN, 40 items) and superiority complex (SUCOMP, 38 items) scales were analyzed. Te examination of their psychometric properties indicated satisfactory psychometric features. Based on the values of communality, item-total correlation and scale principal component saturation, ten items were chosen for shortened scales. Te exploratory factor analysis of the shor- tened scales clearly identifed two factors that represent inferiority and superiority complex. In the second study, the sample consisted of 187 students (53% female). A confrmative factor analysis was carried out. Te structural model consists of two correlated, identifable dimensions and adequate ft indicators. Overall results sugest that the Adlerian con- cepts are adequately operationalized in COMPIN and SUCOPM scales. Tese scales can be valuable research tools in psychological research. Furthermore, shortened COMPIN-10 and SUCOMP-10 scales seem to be useful tools for measuring the inferiority and superiority complex. 1 Filozofski fakultet, Univerzitet u Banjoj Luci, [email protected] 2 ZFMR Dr Miroslav Zotović , Banja Luka 3 Filozofski fakultet, Univerzitet u Banjoj Luci Tis is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Narcissism and the American Dream in Arthur Miller's

Narcissism and the American Dream in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman Narcissism och den amerikanska drömmen i Arthur Millers en handelsresandes död. Fredrik Artan Faculty of Arts and Education Subject: English Points:15.0 Supervisor: Magnus Ullén Examiner: Anna Swärdh 2014-06-18 Serial number Abstract This essay focuses on the theme of the American Dream in relation to narcissism in Miller’s Death of a salesman. The purpose is to demonstrate that a close reading of the main protagonist, Willy Loman, suggests that his notion of success in relation to the American Dream can be regarded as narcissistic. This essay will examine this by first observing how Willy´s notion of success is represented in the play, then look at how his understanding of it can be viewed from a narcissistic standpoint. The results I have found in my analysis show that there is a connection between Willy’s understanding of success and his narcissistic behavior. He displays traits such as grandiosity, arrogance, need of specialness and denial of emotions. His relationship with other characters reveals his lack of empathy, manipulation and exploitation of others as well as his need of superiority and fear of inferiority. The conclusion is that Willy and his notion of success could be considered as narcissistic. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 The American Dream .............................................................................................................................................