Volume XXIV:2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hƒ›R's Blindness and the Pledging of Ó›Inn's

Hƒ›r’s Blindness and the Pledging of Ó›inn’s Eye: A Study of the Symbolic Value of the Eyes of Hƒ›r, Ó›inn and fiórr Annette Lassen The Arnamagnæan Institute, University of Copenhagen The idea of studying the symbolic value of eyes and blindness derives from my desire to reach an understanding of Hƒ›r’s mythological role. It goes without saying that in Old Norse literature a person’s physiognomy reveals his characteristics. It is, therefore, a priori not improbable that Hƒ›r’s blindness may reveal something about his mythological role. His blindness is, of course, not the only instance in the Eddas where eyes or blindness seem significant. The supreme god of the Old Norse pantheon, Ó›inn, is one-eyed, and fiórr is described as having particularly sharp eyes. Accordingly, I shall also devote attention in my paper to Ó›inn’s one-eyedness and fiórr’s sharp gaze. As far as I know, there exist a couple of studies of eyes in Old Norse literature by Riti Kroesen and Edith Marold. In their articles we find a great deal of useful examples of how eyes are used as a token of royalty and strength. Considering this symbolic value, it is clear that blindness cannot be, simply, a physical handicap. In the same way as emphasizing eyes connotes superiority 220 11th International Saga Conference 221 and strength, blindness may connote inferiority and weakness. When the eye symbolizes a person’s strength, blinding connotes the symbolic and literal removal of that strength. A medieval king suffering from a physical handicap could be a rex inutilis. -

Heimskringla III.Pdf

SNORRI STURLUSON HEIMSKRINGLA VOLUME III The printing of this book is made possible by a gift to the University of Cambridge in memory of Dorothea Coke, Skjæret, 1951 Snorri SturluSon HE iMSKrinGlA V oluME iii MAG nÚS ÓlÁFSSon to MAGnÚS ErlinGSSon translated by AliSon FinlAY and AntHonY FAulKES ViKinG SoCiEtY For NORTHErn rESEArCH uniVErSitY CollEGE lonDon 2015 © VIKING SOCIETY 2015 ISBN: 978-0-903521-93-2 The cover illustration is of a scene from the Battle of Stamford Bridge in the Life of St Edward the Confessor in Cambridge University Library MS Ee.3.59 fol. 32v. Haraldr Sigurðarson is the central figure in a red tunic wielding a large battle-axe. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ vii Sources ............................................................................................. xi This Translation ............................................................................. xiv BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES ............................................ xvi HEIMSKRINGLA III ............................................................................ 1 Magnúss saga ins góða ..................................................................... 3 Haralds saga Sigurðarsonar ............................................................ 41 Óláfs saga kyrra ............................................................................ 123 Magnúss saga berfœtts .................................................................. 127 -

Poetry and Society: Aspects of Shona, Old English and Old Norse Literature

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Poetry and Society: Aspects of Shona, Old English and Old Norse Literature Hazel Carter School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 4 One of the most interesting and stimulating the themes, and especially in the use made of developments of recent years in African studies certain poetic techniques common to both. has been the discovery and rescue of the tradi- Compare, for instance, the following extracts, tional poetry of the Shona peoples, as reported the first from the clan praises of the Zebra 1 in a previous issue of this journal. In particular, (Tembo), the second from Beowulf, the great to anyone acquainted with Old English (Anglo- Old English epic, composed probably in the Saxon) poetry, the reading of the Shona poetry seventh century. The Zebra praises are com- strikes familiar chords, notably in the case of plimentary and the description of the dragon the nheternbo and madetembedzo praise poetry. from Beowulf quite the reverse, but the expres- The resemblances are not so much in the sion and handling of the imagery is strikingly content of the poetry as in the treatment of similar: Zvaitwa, Chivara, It has been done, Striped One, Njunta yerenje. Hornless beast of the desert. Heko.ni vaTemho, Thanks, honoured Tembo, Mashongera, Adorned One, Chinakira-matondo, Bush-beautifier, yakashonga mikonde Savakadzu decked with bead-girdles like women, Mhuka inoti, kana yomhanya Beast which, when it runs amid the mumalombo, rocks, Kuatsika, unoona mwoto kuti cheru And steps on them, you see fire drawn cfreru.2 forth. -

GIANTS and GIANTESSES a Study in Norse Mythology and Belief by Lotte Motz - Hunter College, N.Y

GIANTS AND GIANTESSES A study in Norse mythology and belief by Lotte Motz - Hunter College, N.Y. The family of giants plays apart of great importance in North Germanic mythology, as this is presented in the 'Eddas'. The phy sical environment as weIl as the race of gods and men owe their existence ultimately to the giants, for the world was shaped from a giant's body and the gods, who in turn created men, had de scended from the mighty creatures. The energy and efforts of the ruling gods center on their battles with trolls and giants; yet even so the world will ultimately perish through the giants' kindling of a deadly blaze. In the narratives which are concerned with human heroes trolls and giants enter, shape, and direct, more than other superhuman forces, the life of the protagonist. The mountains, rivers, or valleys of Iceland and Scandinavia are often designated with a giant's name, and royal houses, famous heroes, as weIl as leading families among the Icelandic settlers trace their origin to a giant or a giantess. The significance of the race of giants further is affirmed by the recor ding and the presence of several hundred giant-names in the Ice landic texts. It is not surprising that students of Germanic mythology and religion have probed the nature of the superhuman family. Thus giants were considered to be the representatives of untamed na ture1, the forces of sterility and death, the destructive powers of 1. Wolfgang Golther, Handbuch der germanischen Mythologie, Leipzig 1895, quoted by R.Broderius, The Giant in Germanic Tradition, Diss. -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE. -

HAMLET's MILL.Pdf

Hamlet's Mill An essay on myth and the frame of time GIORGIO de SANTILLANA Professor of the History and Philosophy of Science M.l.T. and HERTHA von DECHEND apl. Professor fur Geschichte der Naturivissenschaften ]. W. Goethe-Universitat Frankfurt Preface ASthe senior, if least deserving, of the authors, I shall open the narrative. Over many years I have searched for the point where myth and science join. It was clear to me for a long time that the origins of science had their deep roots in a particular myth, that of invariance. The Greeks, as early as the 7th century B.C., spoke of the quest of their first sages as the Problem of the One and the Many, sometimes describing the wild fecundity of nature as the way in which the Many could be deduced from the One, sometimes seeing the Many as unsubstantial variations being played on the One. The oracular sayings of Heraclitus the Obscure do nothing but illustrate with shimmering paradoxes the illusory quality of "things" in flux as they were wrung from the central intuition of unity. Before him Anaximander had announced, also oracularly, that the cause of things being born and perishing is their mutual injustice to each other in the order of time, "as is meet," he said, for they are bound to atone forever for their mutual injustice. This was enough to make of Anaximander the acknowledged father of physical science, for the accent is on the real "Many." But it was true science after a fashion. Soon after, Pythagoras taught, no less oracularly, that "things are numbers." Thus mathematics was born. -

The Hostages of the Northmen: from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages

Part IV: Legal Rights It has previously been mentioned how hostages as rituals during peace processes – which in the sources may be described with an ambivalence, or ambiguity – and how people could be used as social capital in different conflicts. It is therefore important to understand how the persons who became hostages were vauled and how their new collective – the new household – responded to its new members and what was crucial for his or her status and participation in the new setting. All this may be related to the legal rights and special privileges, such as the right to wear coat of arms, weapons, or other status symbols. Personal rights could be regu- lated by agreements: oral, written, or even implied. Rights could also be related to the nature of the agreement itself, what kind of peace process the hostage occurred in and the type of hostage. But being a hostage also meant that a person was subjected to restric- tions on freedom and mobility. What did such situations meant for the hostage-taking party? What were their privileges and obli- gations? To answer these questions, a point of departure will be Kosto’s definition of hostages in continental and Mediterranean cultures around during the period 400–1400, when hostages were a form of security for the behaviour of other people. Hostages and law The hostage had its special role in legal contexts that could be related to the discussion in the introduction of the relationship between religion and law. The views on this subject are divided How to cite this book chapter: Olsson, S. -

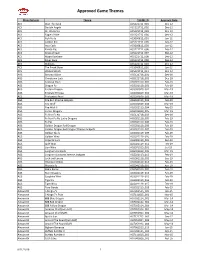

Approved Game Themes

Approved Game Themes Manufacturer Theme THEME ID Approval Date ACS Bust The Bank ACS121712_001 Dec-12 ACS Double Angels ACS121712_002 Dec-12 ACS Dr. Watts Up ACS121712_003 Dec-12 ACS Eagle's Pride ACS121712_004 Dec-12 ACS Fish Party ACS060812_001 Jun-12 ACS Golden Koi ACS121712_005 Dec-12 ACS Inca Cash ACS060812_003 Jun-12 ACS Karate Pig ACS121712_006 Dec-12 ACS Kings of Cash ACS121712_007 Dec-12 ACS Magic Rainbow ACS121712_008 Dec-12 ACS Silver Fang ACS121712_009 Dec-12 ACS Stallions ACS121712_010 Dec-12 ACS The Freak Show ACS060812_002 Jun-12 ACS Wicked Witch ACS121712_011 Dec-12 AGS Bonanza Blast AGS121718_001 Dec-18 AGS Chinatown Luck AGS121718_002 Dec-18 AGS Colossal Stars AGS021119_001 Feb-19 AGS Dragon Fa AGS021119_002 Feb-19 AGS Eastern Dragon AGS031819_001 Mar-19 AGS Emerald Princess AGS031819_002 Mar-19 AGS Enchanted Pearl AGS031819_003 Mar-19 AGS Fire Bull Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_003 Feb-19 AGS Fire Wolf AGS031819_004 Mar-19 AGS Fire Wolf II AGS021119_004 Feb-19 AGS Forest Dragons AGS031819_005 Mar-19 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu AGS121718_003 Dec-18 AGS Fu Nan Fu Nu Lucky Dragons AGS021119_005 Feb-19 AGS Fu Pig AGS021119_006 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon AGS021119_008 Feb-19 AGS Golden Dragon Red Dragon Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_007 Feb-19 AGS Golden Skulls AGS021119_009 Feb-19 AGS Golden Wins AGS021119_010 Feb-19 AGS Imperial Luck AGS091119_001 Sep-19 AGS Jade Wins AGS021119_011 Feb-19 AGS Lion Wins AGS071019_001 Jul-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots AGS031819_006 Mar-19 AGS Longhorn Jackpots Xtreme Jackpots AGS021119_012 Feb-19 AGS Luck -

Viking Tales in 14 Signatures of 4 Pages

The Baby The queen looked at him and smiled and remembered her dream and thought: "That great tree! Can it be this little baby of mine?" 10 The Baby water. The king dipped his hand into it and sprinkled the baby, saying: "I own this baby for my son. He shall be called Harald. My naming gift to him is ten pounds of gold." Then the woman carried the baby back to the queen's room. This is a copy of a Project Gutenberg eBook. It is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Prepared for printing by Meredith Jensen, May 2017. Please visit me at Pobblelane.com for information on binding your own books. Project Gutenberg Transcriber's Note: Minor Picture 2: "I own this baby for my son. He shall be called typographical errors have been corrected without Harald" note. In the Pronouncing Index the up tack “My lord owns him for his son," she said. diacritical mark over a vowel is represented by "And no wonder! He is perfect in every limb." [+a], [+e], [+i] and [+o]. 9 The Baby Some time after that a serving-woman came into the feast hall where King Halfdan was. She carried a little white bundle in her arms. "My lord," she said, "a little son is just born to you." "Ha!" cried the king, and he jumped up from the high seat and hastened forward until he stood before the woman. -

A Case-Study of the German Archaeologist Herbert Jankuhn (1905-1990)

Science and Service in the National Socialist State: A Case-Study of the German Archaeologist Herbert Jankuhn (1905-1990) by Monika Elisabeth Steinel UCL This thesis is submitted for examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) January 2009 DECLARATION I, Monika Elisabeth Steinel, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. January 2009 2 ABSTRACT The thesis investigates the relationship between archaeology, politics and ideology through a case-study of the prominent German archaeologist Herbert Jankuhn (1905- 1990). It addresses the following questions: what role do archaeological scholars assume in a totalitarian state’s organisational structures, and what may motivate them to do so? To what extent and how are archaeologists and their scientific work influenced by the political and ideological context in which they perform, and do they play a role in generating and/or perpetuating ideologies? The thesis investigates the nature and extent of Jankuhn's practical involvement in National Socialist hierarchical structures, and offers a thematically structured analysis of Jankuhn's archaeological writings that juxtaposes the work produced during and after the National Socialist period. It investigates selected components of Herbert Jankuhn's research interests and methodological approaches, examines his representations of Germanic/German pre- and protohistory and explores his adapting interpretations of the early medieval site of Haithabu in northern Germany. The dissertation demonstrates that a scholar’s adaptation to political and ideological circumstances is not necessarily straightforward or absolute. As a member of the Schutzstaffel, Jankuhn actively advanced National Socialist ideological preconceptions and military aims. -

Co-Operation Between the Viking Rus' and the Turkic Nomads of The

Csete Katona Co-operation between the Viking Rus’ and the Turkic nomads of the steppe in the ninth-eleventh centuries MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest May 2018 CEU eTD Collection Co-operation between the Viking Rus’ and the Turkic nomads of the steppe in the ninth-eleventh centuries by Csete Katona (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2018 Co-operation between the Viking Rus’ and the Turkic nomads of the steppe in the ninth-eleventh centuries by Csete Katona (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2018 Co-operation between the Viking Rus’ and the Turkic nomads of the steppe in the ninth-eleventh centuries by Csete Katona (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Supervisor CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2018 I, the undersigned, Csete Katona, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. -

Grímnismál: Acriticaledition

GRÍMNISMÁL: A CRITICAL EDITION Vittorio Mattioli A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2017 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/12219 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence Grímnismál: A Critical Edition Vittorio Mattioli This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 12.11.2017 i 1. Candidate’s declarations: I Vittorio Mattioli, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 72500 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2014 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in September, 2014; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2014 and 2017. Date signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date signature of supervisors 3.