Sir William Bruce: 'The Chief Introducer of Architecture in This Country'1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notices of the King's Master. Weights of Scotland, With

III. NOTICEE KING'TH F SO S MASTER. WEIGHT F SCOTLANDO S , WITH WRIT THEIF SO R APPOINTMENTS . MYLNEREVS E . R TH . Y B ., M.A., B.C.L. OXON. The King's Master Wright was a personage of less importance than the King's Master Mason or the King's Master of Work. Still, the history of his office resembles in many respects that of the two last- named officials, and we find him and his assistants mentioned from tim e earl timo th et yn ei record f Scotlando s e numbeTh . f wrighto r s in the royal employment seems to have varied considerably, according to e variouth s exigencie e Crownth f d theso s an ; e wrights could readily turn their hands to boat-building, the construction of instruments for military warfare, or the internal fittings of the Eoyal Palace. Some notices of the wrights and carpenters employed by the Kings of Scotlandin early times maybe Exchequerfoune th n di Rolls. Thus 129n ,i 0 Alexander Carpentere th , s wor,hi receiver k fo execute y spa Stirlinn di g Castle by the King's command. In 1361 Malcolm, the Wright, receives £10 fro e fermemth f Aberdeeno s d thian ,s payhien repeates i t laten di r years. Between the years 1362 and 1370 Sir William Dishington acted as Master of Work to the Church of St Monan's in Fife, and received from Kine Th g . alsOd of £613 . o pair 7s Kinm fo d, su ge Davith . II d carpenter's wor t thika s 137churcn I , 7. -

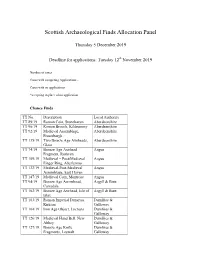

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel Thursday 5 December 2019 Deadline for applications: Tuesday 12th November 2019 Number of cases – Cases with competing Applications - Cases with no applications – *accepting in place of no application Chance Finds TT No. Description Local Authority TT 89/19 Roman Coin, Stonehaven Aberdeenshire TT 90/19 Roman Brooch, Kildrummy Aberdeenshire TT 92/19 Medieval Assemblage, Aberdeenshire Fraserburgh TT 135/19 Two Bronze Age Axeheads, Aberdeenshire Glass TT 74/19 Bronze Age Axehead Angus Fragment, Ruthven TT 109/19 Medieval – Post-Medieval Angus Finger Ring, Aberlemno TT 132/19 Medieval-Post-Medieval Angus Assemblage, East Haven TT 147/19 Medieval Coin, Montrose Angus TT 94/19 Bronze Age Arrowhead, Argyll & Bute Carradale TT 102/19 Bronze Age Axehead, Isle of Argyll & Bute Islay TT 103/19 Roman Imperial Denarius, Dumfries & Kirkton Galloway TT 104/19 Iron Age Object, Lochans Dumfries & Galloway TT 126/19 Medieval Hand Bell, New Dumfries & Abbey Galloway TT 127/19 Bronze Age Knife Dumfries & Fragments, Leswalt Galloway TT 146/19 Iron Age/Roman Brooch, Falkirk Stenhousemuir TT 79/19 Medieval Mount, Newburgh Fife TT 81/19 Late Bronze Age Socketed Fife Gouge, Aberdour TT 99/19 Early Medieval Coin, Fife Lindores TT 100/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Fife St Andrews TT 101/19 Late Medieval/Post-Medieval Fife Seal Matrix, St Andrews TT 111/19 Iron Age Button and Loop Fife Fastener, Kingsbarns TT 128/19 Bronze Age Spearhead Fife Fragment, Lindores TT 112/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Highland Muir of Ord TT -

Site Selection Document: Summary of the Scientific Case for Site Selection

West Coast of the Outer Hebrides Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) No. UK9020319 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Scotland Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed in preparation for possible formal Scotland consultation. 30/06/15 Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Updated with minor amendments to address Marine comments from Marine Scotland Science in Scotland preparation for the SPA stakeholder workshop. 23/02/16 Emma Philip Version 4 Revised format, using West Coast of Outer MPA Hebrides as a template, to address comments Project received at the SPA stakeholder workshop. Steering Emma Philip Group 07/04/16 Version 5 Text updated to reflect proposed level of detail for Marine final versions. Scotland Emma Philip 18/04/16 Version 6 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Glen Tyler & Emma Philip 19/06/16 Version 7 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 20/6/16 Version 8 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 9 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 2. Site summary ..................................................................................................... 2 3. Bird survey information .................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines ................................. 7 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................ 13 6. Information on qualifying species ................................................................. -

Building Stones of Edinburgh's South Side

The route Building Stones of Edinburgh’s South Side This tour takes the form of a circular walk from George Square northwards along George IV Bridge to the High Street of the Old Town, returning by South Bridge and Building Stones Chambers Street and Nicolson Street. Most of the itinerary High Court 32 lies within the Edinburgh World Heritage Site. 25 33 26 31 of Edinburgh’s 27 28 The recommended route along pavements is shown in red 29 24 30 34 on the diagram overleaf. Edinburgh traffic can be very busy, 21 so TAKE CARE; cross where possible at traffic light controlled 22 South Side 23 crossings. Public toilets are located in Nicolson Square 20 19 near start and end of walk. The walk begins at NE corner of Crown Office George Square (Route Map locality 1). 18 17 16 35 14 36 Further Reading 13 15 McMillan, A A, Gillanders, R J and Fairhurst, J A. 1999 National Museum of Scotland Building Stones of Edinburgh. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh Geological Society. 12 11 Lothian & Borders GeoConservation leaflets including Telfer Wall Calton Hill, and Craigleith Quarry (http://www. 9 8 Central 7 Finish Mosque edinburghgeolsoc.org/r_download.html) 10 38 37 Quartermile, formerly 6 CHAP the Royal Infirmary of Acknowledgements. 1 EL Edinburgh S T Text: Andrew McMillan and Richard Gillanders with Start . 5 contributions from David McAdam and Alex Stark. 4 2 3 LACE CLEUCH P Map adapted with permission from The Buildings of BUC Scotland: Edinburgh (Pevsner Architectural Guides, Yale University Press), by J. Gifford, C. McWilliam and D. -

2000 Jaargang 99

Robert Hook Hollandd ean : Dutch influenc architecturs hi n eo e Alison Stoesser-Johnston The use of these publications by English architects and arti- Introductie)!! sans and the design of Wollaton Hall were not based on any Dutch classicism was a recent arrival in England when first-hand personal impressio f classicisno Italymn i . Thid ha s Robert Hooke made his first architectural designs in the late emergence th waio t r fo t f Inigeo o Jone s architectsa visis Hi . t 1660s. 'e constructioPrioth o t r f Hugo n h May's Eltham to Italy in 1613-'14 in the entourage of Thomas Howard, 2nd Lodg 1663-'64n i e e firsth , t exampl f Dutceo h classicisn mi Earl of Arundel, his close interest in Roman antiquities and England, classical elements straight from Italy and via Flan- intimate knowledge of Palladio's drawings are most ders had been used in English architecture for nearly a hund- dramatically exemplifie Banquetins hi n di g Hous f 1619-22eo . red years. Initially these had been mainly of a decorative na- Not only, however, has Jones here used Palladian "vocabulary" ture but vvith the construction of Inigo Jones' Banqueting 7 but hè has combined it with the application of Scamozzian House (1619-'21) there was a dramatic change in the way orders, the Composite being superimposed on the lonic. This classicism was adapted to English architecture. Jones drew combination of Palladian elements with Scamozzian also on the examples of Palladio and Scamozzi in his architecture influence beginninge th d f Dutcso h classicism.8 Jones' design using both Palladio's treatise, / quattro libri, personal know- was not only a major innovation in England but it also inspired ledge of his architecture and, in the case of Scamozzi, per- Jaco n Campe s va bfirs hi tn i narchitectura l commission i n sonal contact e applieH . -

An Old Family; Or, the Setons of Scotland and America

[U AN OLD FAMILY OR The Setons of Scotland and America BY MONSIGNOR SETON (MEMBER OF THE NEW YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY) NEW YORK BRENTANOS 1899 Copyright, 1899, by ROBERT SETON, D. D. TO A DEAR AND HONORED KINSMAN Sir BRUCE-MAXWELL SETON of Abercorn, Baronet THIS RECORD OF SCOTTISH ANCESTORS AND AMERICAN COUSINS IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR Preface. The glories of our blood and state Are shadows, not substantial things. —Shirley. Gibbon says in his Autobiography: "A lively desire of knowing and recording our ancestors so generally prevails that it must depend on the influence of some common principle in the minds of men"; and I am strongly persuaded that a long line of distinguished and patriotic forefathers usually engenders a poiseful self-respect which is neither pride nor arrogance, nor a bit of medievalism, nor a superstition of dead ages. It is founded on the words of Scripture : Take care of a good name ; for this shall continue with thee more than a thousand treasures precious and great (Ecclesiasticus xli. 15). There is no civilized people, whether living under republi- can or monarchical institutions, but has some kind of aristoc- racy. It may take the form of birth, ot intellect, or of wealth; but it is there. Of these manifestations of inequality among men, the noblest is that of Mind, the most romantic that of Blood, the meanest that of Money. Therefore, while a man may have a decent regard for his lineage, he should avoid what- ever implies a contempt for others not so well born. -

Landscape Design and the Work of Sir William Bruce and Alexander Edward', Architectural Heritage, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer A Prospect on Antiquity and Britannia on Edge: Landscape Design and the Work of Sir William Bruce and Alexander Edward Citation for published version: Lowrey, J 2012, 'A Prospect on Antiquity and Britannia on Edge: Landscape Design and the Work of Sir William Bruce and Alexander Edward', Architectural Heritage, vol. 23, pp. 57-74. https://doi.org/10.3366/arch.2012.0033 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/arch.2012.0033 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Architectural Heritage Publisher Rights Statement: © The Architectural Heritage Society. Lowrey, J. (2013). A Prospect on Antiquity and Britannia on Edge: Landscape Design and the Work of Sir William Bruce and Alexander Edward. Architectural Heritage General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 John Lowrey A Prospect on Antiquity and Britannia on Edge: Landscape Design and the Work of Sir William Bruce and Alexander Edward This paper considers the main characteristics of the Scottish formal landscape, as established by Sir William Bruce. -

![The Mylne Family [Microform] : Master Masons, Architects, Engineers, Their Professional Career, 1481-1876](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0899/the-mylne-family-microform-master-masons-architects-engineers-their-professional-career-1481-1876-1410899.webp)

The Mylne Family [Microform] : Master Masons, Architects, Engineers, Their Professional Career, 1481-1876

THE MYLNE FAMILY. MASTER MASONS, ARCHITECTS, ENGINEERS THEIR PROFESSIONAL CAREER 1481-1876. PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION BY ROBERT W. MYLNE, C.E., F.R.S., F.S.A., F.G.S., F.S.A Scot PEL, INST. BRIT. ARCH LONDON 187 JOHN MYLNE, MASTER MASON ANDMASTER OF THE LODGE OF SCONE. {area 1640—45.) Jfyotn an original drawing in tliepossession of W. F. Watson, Esq., Edinburgh. C%*l*\ fA^ CONTENTS. PREFACE. " REPRINT FROM ARTICLEIN DICTIONARYOF ARCHITECTURE.^' 1876. REGISTER 07 ABMB—LTONOFFICE—SCOTLAND,1672. BEPBIKT FBOH '-' HISTOBT OF THKLODGE OF EDINBURGH," 1873. CONTRACT BT THE MASTER MASONS OF THE LODGE OF SCONE AND PERTH, 1658. APPENDIX. EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF DUNDEE, 1567—1604. CONTRACT WITH GEORGE THOMSON AND JOHN MTLNE, MASONS, TO MAKE ADDITIONS TO LORD BANNTAYNE'S HOUSE AT NEWTTLE. NEAR DUNDEE, 1589. — EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF EDINBURGH, 1616 17. CONTRACT BETWIXT JOHN MTLNE,AND LORD SCONE TO BUILD A CHURCH AT FALKLAND,1620. EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF DUNDEE AND ABERDEEN, 1622—27. EXTRACT FROM THE CHAMBEBLAIn'b ACCOUNTS OF THE EABL OF PERTH, 1629. GRANT TOJOHN MTLNEOF THE OFFICE OF PRINCIPAL MASTER MASON TO THEKING,1631. EXTRACTS FBOM THE BUBGH BOOKS OF KIBCALDT AND DUNDEE, 1643—51. GRANT TO JOHN MTLNE, TOUNGER, KING'S PRINCIPAL MASTER MASON> OF THE OFFICE OF CAPTAIN AND MASTER OF PIONEERS AND PRINCIPAL MASTER GUNNER OF ALLSCOTLAND,1646. CONTRACT WITHJOHN MTLNEAND GEORGE 2ND EABL 09 PANMUBE TO BUILDPANMURE HOUSE, ADJACENT TO THE ANCIENT MANSION AT BOWBCHIN, NEAR DUNDEE, 1666. BOTAL WARRANT CONCERNING THE FINISHING OF THE PALACE OF HOLTROOD, 21 FEBRUARY,1676. -

The Design of the English Domestic Library in the Seventeenth Century: Readers and Their Book Rooms

The Design of the English Domestic Library in the Seventeenth Century: Readers and Their Book Rooms Lucy Gwynn Abstract The seventeenth century saw the increase in size of book collec- tions in private hands. Domestic library collections were becoming more visible as important adjuncts to the lives of their socially and culturally engaged owners. This article explores the ways in which the practical and intellectual problems of storing books were ad- dressed in the English home, through inventories and buildings accounts as well as contemporary literature. The changes in library furniture design over the course of the century are traced, together with the emergence of formal organizing systems such as catalogues and subject classification. Finally, the adoption of a different stylistic approach is examined. From Renaissance paintings of scholar saints like Jerome and Augustine to modern cinema’s portrayals of wizards and academics, the image of the private library has remained surprisingly consistent. The rooms belonging to Gandalf, Dumbledore, and John Dee (in Shekhar Kapur’s Elizabeth: the Golden Age), cluttered as they are with scientific instruments, taxidermy, and tottering piles of books, are striking in their resemblance to the humanist models represented by Carpaccio and Antonello da Messina. Bonnie Mak and Dora Thornton have demonstrated that the libraries of Renaissance Italy were as deliberately and artificially designed as their cinematic copies (Mak, 2002; Thornton, 1998). The books themselves be- came representative of their contents through their display, and the pres- ence of trompe l’oeil effects exaggerated the use of the study as a “theatri- cal space for self-exhibition” (Mak, 2002, p. -

Panel Carved with the Arms of Mary of Guise

PMSA NRP: Work Record Ref: EDIN0721 03-Jun-11 © PMSA RAC Panel Carved with the Arms of Mary of Guise 773 Carver: Unknown Town or Village Parish Local Govt District County Edinburgh Edinburgh NPA The City of Edinburgh Council Lothian Area in town: Old Town Road: Palace of Holyroodhouse Location: North-west end, between 1st floor windows, of Palace of Holyroodhouse A to Z Ref: OS Ref: Postcode: Previously at: Setting: On building SubType: Public access with entrance fee Commissioned by: Year of Installation: 1906 Details: Design Category: Animal Category: Architectural Category: Commemorative Category: Heraldic Category: Sculptural Class Type: Coat of Arms SubType: Define in freetext of Mary of Guise Subject Non Figurative SubType: Full Length Part(s) of work Material(s) Dimensions > Whole Stone Work is: Extant Listing Status: I Custodian/Owner: Royal Household Condition Report Overall Condition: Good Risk Assessment: No Known Risk Surface Character: Comment No damage Vandalism: Comment None Inscriptions: At base of panel (raised letters): M. R Signatures: None Physical Panel carved in high relief. An eagle with a crown around its neck stands in profile (facing S.) holding a Description: diamond-shaped shield in its left foot. The shield is quartered with a small shield at its centre. Behind the eagle are lilies and below are the initials M. R flanked by fleurs de lis Person or event Mary of Guise commemorated: History of Commission : Exhibitions: Related Works: Legal Precedents: References: J. Gifford, C. McWilliam, D. Walker and C. Wilson, -

ANON-KU2U-GFJG-5 Supporting Info Name Nicolas Lopez Email [email protected] Response

Customer Ref: 01234 Response Ref: ANON-KU2U-GFJG-5 Supporting Info Name Nicolas Lopez Email [email protected] Response Type Developer / Landowner On behalf of: Defence Infrastructure Organisation Choice 1 A We want to connect our places, parks and green spaces together as part of a city-wide, regional, and national green network. We want new development to connect to, and deliver this network. Do you agree with this? - Select support / don't support Short Response Not Answered Explanation Choice 1 B We want to change our policy to require all development (including change of use) to include green and blue infrastructure. Do you agree with this? - Support / Object Short Response No Explanation The DIO is concerned about the requirement for changes of use to incorporate new blue and green infrastructure. As the Council will be aware, the Redford Barracks site incorporates a number of listed buildings that may be retained and converted to residential accommodation as part of a wider scheme to redevelop the site. It would be challenging to retro-fit new blue/green infrastructure for these buildings and in terms of drainage it would be much less invasive to continue to rely upon existing systems. This policy would also be incompatible with the conversion of buildings with constrained curtilages which have little or no space to install features like swales or rain gardens. These issues will be further compounded for buildings that are listed or within conservation areas where the retro-fitting of blue/green infrastructure on the building itself, such as a green roof, would not be feasible or indeed desirable from a built heritage perspective. -

2017 ELAFN Soc Transactions Vol XXXI

TRANSACTIONS OF THE EAST LOTHIAN ANTIQUARIAN AND FIELD NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY VOL. XXXI 2017 TRANSACTIONS OF THE EAST LOTHIAN ANTIQUARIAN AND FIELD NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY THIRTY-FIRST VOLUME 2017 ISSN 0140 1637 HADDINGTON DESIGNED BY DAWSON CREATIVE (www.dawsoncreative.co.uk) AND PRINTED BY EAST LOTHIAN COUNCIL PRINT UNIT FOR MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY i THE EDITOR OF THE TRANSACTIONS Chris Tabraham ([email protected]) welcomes contributions for the next Transactions (VOL XXXII) Front cover illustration: Pencaitland Kirk from the north-east, drawn by Alexander Archer, December 1848. The building is a fine example of a medieval kirk remodelled for Reformed worship following the passing of the Act of Reformation in 1560. (Courtesy of RCAHMS.) Back cover illustration: Bust of Robert Brown of Markle (1756 - 1831), the noted authority on agricultural subjects, and famed for serving as conductor (editor) of The Farmer’s Magazine from its inception in January 1800 to December 1812. The bust is in the collection of David Ritchie, Robert Brown’s great-great-grandson. (Photo: David Henrie.) Further information about the society can be found on the website: http://eastlothianantiquarians.org.uk/ ii CONTENTS AN ICONIC MONUMENT REVISITED: THE GOBLIN HA’ IN YESTER CASTLE by KATHY FAIRWEATHER, BILL NIMMO & PETER RAMAGE 1 THE TOWER HOUSE AS HOME: ELPHINSTONE TOWER: A CASE STUDY by Dr ALLAN RUTHERFORD 22 ALTARS OUT: PULPITS IN!: THE FIRST POST-REFORMATION KIRKS IN EAST LOTHIAN PART ONE: NEW BROOMS by BILL DODD 44 CLARET, COUNCILLORS AND CORRUPTION: THE HADDINGTON ELECTION OF 1753 by ERIC GLENDINNING 64 AN AUTHORITY ON AGRICULTURAL SUBJECTS: ROBERT BROWN OF MARKLE, 1756-1831 by JOY DODD 82 FATHER AND SON: TWO GENERATIONS OF BAIRDS AT NEWBYTH by DAVID K.