Negation, Doubling and Identity in Roman Polanski's the Tenant and Max Frisch's Stiller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Information About Poland - Climate

CONTENTS: 1. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT POLAND - CLIMATE .................................................3 - GEOGRAPHY ...........................................4 - BRIEF HISTORY ........................................4 - MAJOR CITIES .........................................5 - FAMOUS PEOPLE .....................................6 2. USEFUL INFORMATION - LANGUAGE ...........................................11 - NATIONAL HOLIDAYS ............................14 - CURRENCY ............................................15 - AVERAGE COSTS ...................................15 - TRADITIONAL CUISINE............................16 - BEFORE YOUR COMING – CHECK-LIST ...17 3. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT RADOM - HISTORY OF RADOM .............................18 - EVENTS .................................................19 - GETTING TO RADOM FROM WARSAW ..21 - PUBLIC TRANSPORT in RADOM .............21 - MUST SEE PLACES .................................22 - WHERE TO GO… ...................................25 - WHERE TO EAT… ..................................25 - WHERE TO PARTY… ..............................26 4. EVERYDAY THINGS - LAW ......................................................27 - IMPORTANT CONTACT INFORMATION ...27 - ACCOMMODATION ...............................27 - HOTELS - HALLS OF RESIDENCE - YOUTH HOSTELS - HELP .....................................................28 - EMERGENCY CALLS - EMERGENCY CONTACT: - POLICE OFFICES - HOSPITALS - CHEMISTRIES - EXCHANGE OFFICES - POST OFFICES - SHOPPING ...........................................29 5. -

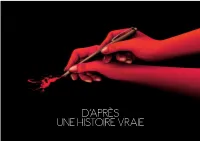

D-Apres-Une-Histoire-Vraie-Dossier-De

WASSIM BÉJI PRÉSENTE EMMANUELLE EVA SEIGNER GREEN UN FILM DE ROMAN POLANSKI SCÉNARIO OLIVIER ASSAYAS ET ROMAN POLANSKI D’APRÈS LE ROMAN DE DELPHINE DE VIGAN, ÉDITIONS JEAN-CLAUDE LATTÈS MUSIQUE ALEXANDRE DESPLAT DISTRIBUTION DURÉE : 1H40 PRESSE MARS FILMS ANDRÉ-PAUL RICCI ET TONY ARNOUX ER 66, RUE DE MIROMESNIL SORTIE LE 1 NOVEMBRE 6, PLACE DE LA MADELEINE 75008 PARIS 75008 PARIS TÉL. : 01 56 43 67 20 TÉL. : 01 49 53 04 20 [email protected] PHOTOS ET DOSSIER DE PRESSE TÉLÉCHARGEABLES SUR WWW.MARSFILMS.COM [email protected] SYNOPSIS Delphine est l’auteur d’un roman intime et consacré à sa mère devenu best-seller. Déjà éreintée par les sollicitations multiples et fragilisée par le souvenir, Delphine est bientôt tourmentée par des lettres anonymes l’accusant d’avoir livré sa famille en pâture au public. La romancière est en panne, tétanisée à l’idée de devoir se remettre à écrire. Son chemin croise alors celui de Elle. La jeune femme est séduisante, intelligente, intuitive. Elle comprend Delphine mieux que personne. Delphine s’attache à Elle, se confie, s’abandonne. Alors qu’Elle s’installe à demeure chez la romancière, leur amitié prend une tournure inquiétante. Est-elle venue combler un vide ou lui voler sa vie ? ENTRETIEN AVEC ROMAN POLANSKI D’APRÈS UNE HISTOIRE VRAIE est tiré du roman de Delphine Était-ce la seule raison ? Le livre de Delphine de Vigan Pensiez-vous déjà au couple formé par Emmanuelle Seigner de Vigan. Qu’est-ce qui vous a attiré dans ce récit ? contient beaucoup de vos thèmes de prédilection : ce et Eva Green pour les interpréter ? jeu de miroirs entre réalité et fiction qui anime les deux Je n’avais lu aucun des livres de Delphine de Vigan. -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

National Film Registry Titles Listed by Release Date

National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year Title Released Inducted Newark Athlete 1891 2010 Blacksmith Scene 1893 1995 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894-1895 2003 Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 2015 The Kiss 1896 1999 Rip Van Winkle 1896 1995 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 2012 Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 2002 President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 2000 The Great Train Robbery 1903 1990 Life of an American Fireman 1903 2016 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 1998 Interior New York Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street 1905 2017 Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 2015 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 2005 A Trip Down Market Street 1906 2010 A Corner in Wheat 1909 1994 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 2004 Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 2003 Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 2005 White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 2008 Little Nemo 1911 2009 The Cry of the Children 1912 2011 A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 2011 From the Manger to the Cross 1912 1998 The Land Beyond the Sunset 1912 2000 Musketeers of Pig Alley 1912 2016 Bert Williams Lime Kiln Club Field Day 1913 2014 The Evidence of the Film 1913 2001 Matrimony’s Speed Limit 1913 2003 Preservation of the Sign Language 1913 2010 Traffic in Souls 1913 2006 The Bargain 1914 2010 The Exploits of Elaine 1914 1994 Gertie The Dinosaur 1914 1991 In the Land of the Head Hunters 1914 1999 Mabel’s Blunder 1914 2009 1 National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year -

Discurso E(M) Imagem Sobre O Feminino: O Sujeito Nas Telas

JONATHAN RAPHAEL BERTASSI DA SILVA DISCURSO E(M) IMAGEM SOBRE O FEMININO: O SUJEITO NAS TELAS Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da USP, como parte das exigências para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências, Área: Psicologia. Orientadora: Profª Drª Lucília Maria Sousa Romão Ribeirão Preto 2012 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Silva, Jonathan Raphael Bertassi da Discurso e(m) imagem sobre o feminino: o sujeito nas telas. Ribeirão Preto, 2010. 220 p. : il. ; 30 cm Dissertação de Mestrado, apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto/USP. Área de concentração: Psicologia. Orientador: Romão, Lucília Maria Sousa. 1. Análise do Discurso. 2. Cinema. 3. Feminino. 4. Sexualidade. 5. Imaginário. FOLHA DE APROVAÇÃO Nome: SILVA, Jonathan Raphael Bertassi da Título: Discurso e(m) imagem sobre o feminino: o sujeito nas telas Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da USP, como parte das exigências para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências, Área: Psicologia. Aprovado em: __________/__________/ __________ Banca Examinadora Prof. Dr._________________________________________________________________ Instituição:______________________________Assinatura:________________________ Prof. Dr._________________________________________________________________ Instituição:______________________________Assinatura:________________________ -

Transnationalism, Displacement and Identitarian Crisis in Roman Polanski‟S the Ghost Writer

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Universidad de Zaragoza Exiled From the Absolute: Transnationalism, Displacement and Identitarian Crisis in Roman Polanski‟s The Ghost Writer Andrés Bartolomé Leal Master thesis supervised by: Prof. Celestino Deleyto Alcalá Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Dpto. De Filología Inglesa y Alemana Universidad de Zaragoza November 2012 Contents | Introduction: Exiled from the Absolute | 2 Story telling and Cinematic Visuality | 9 From National to Transnational Cinema | 13 The Transnational Cinema of Roman Polanski | 20 Roman Polanski: An author on the Move | 22 The Ghost Writer | 30 Production | 30 International Relations and National Sovereignties | 31 Political Exile, Nostalgia and Entrapment | 35 An Outsider‟s Perspective: Voyeurism and Fragmentation | 43 Of Havens and Prisons: Visual Style and Spatial Inscription | 53 Conclusion | 67 Works Cited | 71 Films Cited | 75 1 Introduction: Exiled from the Absolute. The aim of this paper is to analyze Roman Polanski‟s film The Ghost Writer (2010) from a „transnational‟ perspective, that is, as a text that, while considering the idea of nation and its borders as paramount elements of our times and identities, focuses on the anxiety and unease that it means for humans to be inevitably subjected to their sovereignty. To do so, I shall, first, introduce the socio-political and cultural changes that have affected our perception of the absoluteness of the frontier, that “elusive line, visible and invisible, physical, metaphorical, amoral and moral” (Rushdie 2002: 78) that limits our existences and identities, and its slippery ontology. Secondly, I shall reflect on the reasons why cinema has as a whole become such a powerful symbol and channel for all the changes that define our post-modern times, and, more precisely, on how transnational cinema‟s contestation of national limitations suits the human experience of the last century so well. -

Clockwork Gente Di Cinema Collana Diretta Da Augusto Sainati

Clockwork gente di cinema Collana diretta da Augusto Sainati Comitato scientifico Sandro Bernardi, Italo Moscati, Ranieri Polese 1.1. ClaudioClaudio Carabba,Carabba, GiovanniGiovanni M.M. RossiRossi (a(a curacura di),di), LaLa vocevoce didi dentro.dentro. IlIl cinemacinema didi ToniToni ServilloServillo,, 2012,2012, pp.pp. 126,126, ill.ill. 2.2. DanieleDaniele Dottorini,Dottorini, FilmareFilmare dall’abisso.dall’abisso. SulSul cinemacinema didi JamesJames CameronCameron,, 2013,2013, pp.pp. 132,132, ill.ill. 3.3. GabrieleGabriele Rizza,Rizza, ChiaraChiara TognolottiTognolotti (a(a curacura di),di), IlIl grandegrande incantatore.incantatore. IlIl cinemacinema didi TerryTerry GilliamGilliam,, 2013,2013, pp.pp. 128,128, ill.ill. 4.4. MarcoMarco Luceri,Luceri, LuigiLuigi NepiNepi (a(a curacura di),di), L’uomoL’uomo deidei sogni.sogni. IlIl cinemacinema didi GiuseppeGiuseppe TornatoreTornatore,, 2014,2014, pp.pp. 128,128, ill.ill. 5.5. LuciaLucia DiDi Girolamo,Girolamo, PerPer amoreamore ee perper gioco.gioco. SulSul cinemacinema didi PedroPedro AlmoAlmo-- dovardovar,, 2015,2015, pp.pp. 160,160, ill.ill. 6.6. EdoardoEdoardo BecattiniBecattini (a(a curacura di),di), CuoreCuore didi tenebra.tenebra. IlIl cinemacinema didi DarioDario ArgentoArgento,, 2015,2015, pp.pp. 128,128, ill.ill. 7.7. IveliseIvelise Perniola,Perniola, GilloGillo PontecorvoPontecorvo oo deldel cinemacinema necessarionecessario,, 2016,2016, pp.pp. 136,136, ill.ill. 8.8. DanielaDaniela BrogiBrogi (a(a curacura di),di), LaLa donnadonna visibile.visibile. IlIl cinemacinema didi StefaniaStefania SandrelliSandrelli,, 2016,2016, pp.pp. 144,144, ill.ill. 9.9. GiovanniGiovanni M.M. Rossi,Rossi, MarcoMarco VanelliVanelli (a(a curacura di),di), PianiPiani didi luce.luce. LaLa cinecine-- matografiamatografia didi VittorioVittorio StoraroStoraro,, 2017,2017, pp.pp. 126,126, ill.ill. -

Oliver Twist in Roman Polanski’S Film “Oliver Twist”

AN ANALYSIS OF INFERIORITY FEELING FACED BY OLIVER TWIST IN ROMAN POLANSKI’S FILM “OLIVER TWIST” THESIS BY: WINAROH ANDANI 07360072 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MUHAMMADIYAH MALANG 2012 i AN ANALYSIS OF INFERIORITY FEELING FACED BY OLIVER TWIST IN ROMAN POLANSKI’S FILM “OLIVER TWIST” THESIS This thesis is submitted to meet one of the requirements to achieve Sarjana Degree in English Education BY: WINAROH ANDANI 07360072 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MUHAMMADIYAH MALANG OCTOBER 2012 ii This thesis written by Winaroh Andani was approved on October 24th, 2012. By: Advisor I, Advisor II, Rina Wahyu Setyaningrum, M. Ed. Dian Inayati, M. Ed. iii This thesis was defended in front of the examiners of the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education of University of Muhammadiyah Malang and accepted as one of the requirements to achieve Sarjana Degree in English Education on October 24th, 2012 Approved by: Faculty of Teacher Training and Education University of Muhammadiyah Malang Dean, Dr. M. Syaifuddin, M. M Examiners: Signatures: 1. Dra. Erly wahyuni, M.Si 1. ………………………. 2. Rahmawati Khadijah Maro, S. Pd, M. PEd 2. ………………………. 3. Rina Wahyu Setyaningrum, M. Ed. 3. ………………………. 4. Dian Inayati, M. Ed. 4. …………………….... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Alhamdulillah, all praise be to Allah SWT, the Merciful and Charitable. Because of the guidance, blessing and affection, the writer can finish this thesis. The writer would like to express her deepest gratitude to Rina Wahyuni Setyaningrum, M. Ed, her first advisor and Dian Inayati, M. Ed, her second advisor, for their suggestions, valuable guidance and advice during the consultation period, and their comments and corrections during the completion of this thesis. -

Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood

FRAMING FEMININITY AS INSANITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF MENTAL ILLNESS IN WOMEN IN POST-CLASSICAL HOLLYWOOD Kelly Kretschmar, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Harry M. Benshoff, Major Professor Sandra Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Debra Mollen, Committee Member Ben Levin, Program Coordinator Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kretschmar, Kelly, Framing Femininity as Insanity: Representations of Mental Illness in Women in Post-Classical Hollywood. Master of Arts (Radio, Television, and Film), May 2007, 94 pp., references, 69 titles. From the socially conservative 1950s to the permissive 1970s, this project explores the ways in which insanity in women has been linked to their femininity and the expression or repression of their sexuality. An analysis of films from Hollywood’s post-classical period (The Three Faces of Eve (1957), Lizzie (1957), Lilith (1964), Repulsion (1965), Images (1972) and 3 Women (1977)) demonstrates the societal tendency to label a woman’s behavior as mad when it does not fit within the patriarchal mold of how a woman should behave. In addition to discussing the social changes and diagnostic trends in the mental health profession that define “appropriate” female behavior, each chapter also traces how the decline of the studio system and rise of the individual filmmaker impacted the films’ ideologies with regard to mental illness and femininity. Copyright 2007 by Kelly Kretschmar ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................ 5 Women and Mental Illness in Classical Hollywood ............................... -

Filmmuseum Im Münchner Stadtmuseum · St.-Jakobs-Platz 1 · 80331 München · Tel 089/233 96450 Donnerstag, 7

Donnerstag, 31. August 2017 19.00 Internationale Koshu saho Tōkyō kembutsu Seite 3 Stummfilmtage (Wie man sich in Tokio benimmt) JP 1926 | Kaname Mori | 57 min | OmeU | \ Masako Ohta La chute de la maison Usher (Der Untergang des Hauses Usher) FR 1928 | Jean Epstein | 62 min | OmU | \ Joachim Bärenz 2 Stefan Drößler Freitag, 1. September 2017 18.30 Internationale Peau de pêche (Pfirsichhaut) Seite 3 Stummfilmtage FR 1929 | Jean Benoît-Lévy, Marie Epstein | 89 min | OmU | \ Richard Siedhoff 21.00 Internationale The Goat (Der Sündenbock) Seite 4 Stummfilmtage USA 1921 | Buster Keaton, Malcolm St. Clair | 20 min | OF The Informer (Die Nacht nach dem Verrat) GB 1929 | Arthur Robison | 83 min | OF | \ Joachim Bärenz Samstag, 2. September 2017 18.30 Internationale Die kleine Veronika Seite 4 Stummfilmtage AT 1930 | Robert Land | 82 min | \ Joachim Bärenz 21.00 Internationale Frankenstein Seite 4 Stummfilmtage USA 1910 | J. Searle Dawley | 16 min | OF Branding Broadway USA 1918 | William S. Hart | 59 min | OF | \ Richard Siedhoff Sonntag, 3. September 2017 18.30 Internationale Zhi Guo Yuan (Romanze eines Obsthändlers) Seite 4 Stummfilmtage China 1922 | Shichuan Zhang | 22 min | OmU Hříchy lásky (Sünden der Liebe) CS 1929 | Karel Lamač | 73 min | OmU | \ Richard Siedhoff 21.00 Internationale Alice's Egg Plant (Alices Hühnerfarm) Seite 5 Stummfilmtage USA 1925 | Walt Disney | 9 min | OF Der Adjutant des Zaren DE 1929 | Vladimir Strijewskij | 98 min | dän.OmU | \ Günter A. Buchwald Dienstag, 5. September 2017 18.30 Internationale The American Venus – Trailer Seite 5 Stummfilmtage USA 1926 | Frank Tuttle | 2 min | OF A Woman of the World (Eine Frau von Welt) USA 1925 | Malcolm St. -

Verleihkatalog Download

VERLEIHKATALOG / LOAN PRINTS 2017 SORTIERT NACH TITEL / ASSORTED BY TITLE 08/15 - ERSTER TEIL (NULL ACHT FÜNFZEHN) Paul May BRD 1954 95 min OV / – 35 mm 08/15 - ZWEITER TEIL (NULL ACHT FÜNFZEHN) Paul May BRD 1955 110 min OV / – 35 mm 1. APRIL 2000 Wolfgang Liebeneiner AT 1952 105 min OV / – 35 mm 1789 Ariane Mnouchkine FR 1974 150 min OV / d 35 mm 1ER FESTIVAL EUROPÉENNE DE JAZZ Harold Cousins FR 1957 18 min OV / – 35 mm 2046 Wong Kar-Wai HK 2004 129 min OV / df 35 mm 8 1/2 WOMEN Peter Greenaway UK 1999 118 min OV / df 35 mm A Jan Lenica BRD 1965 10 min D / – 35 mm A BEAUTIFUL MIND Ron Howard US 2001 135 min OV / df 35 mm À BOUT DE SOUFFLE Jean-Luc Godard FR 1960 90 min OV / d 35 mm A BRIEF HISTORY OF TIME Errol Morris UK 1991 91 min OV / d 35 mm A CHAIRY TALE Norman McLaren CA 1957 12 min OV / – 35 mm A DANGEROUS METHOD David Cronenberg UK/DE/CA/C 2011 99 min OV / df 35 mm A DOLL'S HOUSE Joseph Losey UK/FR 1973 106 min OV / df 35 mm A KING IN NEW YORK Charles Chaplin UK 1957 110 min OV / – 35 mm A LIFE LESS ORDINARY Danny Boyle US/UK 1997 103 min OV / df 35 mm À NOUS LA LIBERTÉ René Clair FR 1931 104 min OV / d 35 mm A PRAIRIE HOME COMPANION / ROBERT ALTMAN’S LAST RADIO SHOW Robert Altman US 2006 105 min OV / df 35 mm Kinemathek Le Bon Film | Theaterstr. -

Film Fiction | Yanvar, №5 1

Film Fiction | Yanvar, №5 1 Film Fiction | Yanvar, №5 2 FİLM FİCTİON Fevral, №6 №6 “Film Fiction”ın 6-cı – fevral sayı artıq ixtiyarınızdadır. Bu say digərlərinə nisbətən Film Fiction daha həcmlidir. Bunu özünüz də görəcəksiniz. Bu sayda bir az fərqliliklər 2012 / Fevral №6 etdik. Yeni rubrikalara aid məqalələrlə tanış olacaqsınız. Bəzi məqamlarda bir az Üz qabığındakı sima: Benisio Del Toro qısaltmalara yol verdik. Filmlər haqqında məqalələri daha da çoxaltdıq. Hər dəfə daha çox filmlərlə sizə tanış etməyə çalışacağıq. Hər dəfə olduğu kimi bu sayımız da bir kino REDAKTOR: Şahin Xəlil adamına həsr olunur. Jurnalın fevral DİZAYN: Ferat buraxılışı Azərbaycan kino və teatrının ən YAZARLAR: Ferat, Şahin Xəlil böyük aktyorlarından biri olan Əliabbas Məcid Məcidov, Mətləb Muxtarov, Pərvanə Qədirovun əziz xatirəsinə həsr olunur. Mirzoyeva TƏRTİBAT: Ferat KORREKTOR: Lalə Mikayıl e-mail: [email protected] facebook səhifəsi: facebook.com/fiction.magazine facebook.com/filmoqrafiya İnformasiya dəstəyi: twitter hesabı: twitter.com/filmfiction Jurnaldakı məqalələrdən istifadə edərkən müəllif hüquqlarını qorumaq mütləqdir. Hər bir yazıya görə müəllif məsuliyyət daşıyır. Film Fiction © 2011-2012 Film Fiction | Yanvar, №5 3 Bu sayımızda Səhifə 4 / Rejissor: Roman Polanski Səhifə 55 / Universal Studios Müəllif: Ferat Müəllif: Məcid Məcidov Səhifə 8 / Aktyor: Benicio Del Toro Səhifə 56/ Təqvim Müəllif: Şahin Xəlil Hazırladı: Şahin Xəlil Səhifə 10 / Aktrisa: Julia Roberts Səhifə 57 / Film: 3-İron Müəllif: Pərvanə Mirzoyeva Müəllif: Ferat Səhifə 14 / TOP