Gaps and Recaps: Exploring the Binge-Published Television Serial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORANGE IS the NEW BLACK PILOT Written By: Jenji Kohan

ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK PILOT Written by: Jenji Kohan Based on the Memoir by Piper Kerman Writer's first 5/22/12 BATHING MONTAGE: We cycle through a series of scenes with voice overs. Underneath the dialogue, one song plays throughout. Perhaps it’s ‘Tell Me Something Good,’ by Rufus and Chaka Khan or something better or cheaper or both that the music supervisor finds for us. INT. CONNECTICUT KITCHEN - DAY - 1979 A beautiful, fat, blonde baby burbles and splashes in a kitchen sink. A maternal hand pulls out the sprayer and gently showers the baby who squeals with joy. PIPER (V.O.) I’ve always loved getting clean. CUT TO: INT. TRADITIONAL BATHROOM - 1984 Five year old Piper plays in a bathtub surrounded by toys. PIPER (V.O.) Water is my friend. CUT TO: INT. GIRLY BATHROOM - 1989 Ten year old Piper lathers up and sings her heart out into a shampoo bottle. PIPER (V.O.) I love baths. I love showers. CUT TO: INT. DORM BATHROOM - 1997 Seventeen year old Piper showers with a cute guy. PIPER (V.O.) I love the smell of soaps and salts. CUT TO: INT. LOFT BATHROOM - 1999 Twenty year old Piper showers with a woman. (ALEX) ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK "Pilot" JENJI DRAFT 2. PIPER (V.O.) I love to lather. CUT TO: INT. DAY SPA - 2004 Piper sits in a jacuzzi with girlfriends. PIPER (V.O.) I love to soak. CUT TO: INT. APARTMENT - 2010 Piper in a clawfoot tub in a brownstone in Brooklyn with LARRY. PIPER (V.O.) It’s my happy place. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Calabasas City Los Angeles County California, U

CALABASAS CITY LOS ANGELES COUNTY CALIFORNIA, U. S. A. Calabasas, California Calabasas, California Calabasas is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, Calabasas es una ciudad en el condado de Los Ángeles, California, Estados located in the hills west of the San Fernando Valley and in the northwest Santa Unidos, ubicada en las colinas al oeste del valle de San Fernando y en el noroeste Monica Mountains between Woodland Hills, Agoura Hills, West Hills, Hidden de las montañas de Santa Mónica, entre Woodland Hills, Agoura Hills, West Hills, Hills, and Malibu, California. The Leonis Adobe, an adobe structure in Old Hidden Hills y Malibu, California. El Adobe Leonis, una estructura de adobe en Town Calabasas, dates from 1844 and is one of the oldest surviving buildings Old Town Calabasas, data de 1844 y es uno de los edificios más antiguos que in greater Los Angeles. The city was formally incorporated in 1991. As of the quedan en el Gran Los Ángeles. La ciudad se incorporó formalmente en 1991. A 2010 census, the city's population was 23,058, up from 20,033 at the 2000 partir del censo de 2010, la población de la ciudad era de 23.058, en census. comparación con 20.033 en el censo de 2000. Contents Contenido 1. History 1. Historia 2. Geography 2. Geografía 2.1 Communities 2.1 Comunidades 3. Demographics 3. Demografía 3.1 2010 3.1 2010 3.2 2005 3.2 2005 4. Economy 4. economía 4.1. Top employers 4.1. Mejores empleadores 4.2. Technology center 4.2. -

The West Wing Weekly 5.04: “Han” Guest: Paula Yoo

The West Wing Weekly 5.04: “Han” Guest: Paula Yoo [Frédéric Chopin – Prelude in E-minor (Op.28, No.4) excerpt] HRISHI: Here we go. JOSH: Hi guys. Wipe away those tears and listen to The West Wing Weekly. There's hope, there's always hope. [laughter] I'm Joshua Malina. HRISHI: And I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: For those of you wondering, I was playing left hand, [Hrishi laughs] and Hrishi was playing right hand. HRISHI: Today, we're talking about “Han.” It's episode 4 of season 5 of The West Wing. JOSH: This episode was written by Peter Noah. Peter Noah would later go on to many things, including being a consulting producer on, I believe, 40 episodes of Scandal. He's a great writer, and story credit for this episode goes to Peter Noah and Mark Goffman. That's Peter Noah & Mark Goffman and, A-N-D, Paula Yoo. The direction is by the always-magnificent Christopher Misiano. The episode first aired on October 22nd, 2003. HRISHI: In this episode, a North Korean pianist comes to the White House for a performance, but things get complicated when he tells the president he wants to defect. C.J.'s for it, but everyone else is pretty much against it, and the president has to weigh both arguments. Meanwhile, Will is having a hard time writing an inspiring speech about the nomination and confirmation of vice president-to-be Bob Russell. Josh is battling one congressman who plans to be a holdout vote against the nomination. Toby wants to get away from speechwriting, but every time he thinks he's out, they keep pulling him back in. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

The Representation of Latinas in Orange Is the New Black a Thesis

The Representation of Latinas in Orange Is the New Black A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University By Sarah Weatherford Millette Bachelor of Arts Furman University, 2011 Director: Ricardo F. Vivancos Pérez, Associate Professor Department of Modern and Classical Languages Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ricardo F. Vivancos Pérez, who has believed in me, encouraged me, and never stopped challenging me. I would also like to thank Dr. Lisa Rabin and Dr. Michele Back for their guidance and their time. Thank you to my family and friends for understanding my less-than-social life these past few months. Finally, I would like to thank my new husband, Nick, for accepting the fact that this has been my first love and priority in our first year of marriage. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract................................................................................................................................ iv Introduction........................................................................................................................... 1 Thesis Overview ................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter One - Gender, Sexuality, and Interethnic Relationships in the Fictional Prison .. 12 Women in the US Prison System................................................................................. -

December 2007

CAMPUS SPOTLIGHT Charlize Filbin sleeping, drooling girl at the FAC EDITOR-IN-CHIEF David Strauss But soft! Mine eyes must be whilst I need to print a paper Turn-ons: not having to get minority study groups, study buddies FEATURES EDITOR Bradley Jackson fries with your Wendy’s combo, who are just a bit too excited to be whispering unto me the most for philosophy. I would wake NEWS EDITOR Kathryn Edwards fantastic of falsehoods, for it thee, but I shall wait instead, for diet Red Bull, all-nighters, flannel study buddies, looking presentable could not be thee, O sleeping, I would sooner fail a thousand pants, headbands, side ponytails, DESIGN EDITOR Matt Hutcheson your ex-boyfriend’s sweatshirt, Motto: “(Snort), what...are you talk- drooling FAC girl, the perfect hu- philosophy papers, and endure ing to me?” PHOTO EDITOR Veronica Hansen man form beneath a tent of flan- the tempestuous gall of my Old Navy flip-flops, flexible-framed glasses, procrastination, sound- ART EDITOR Chris Friend nel and elastic waistbands. embittered TA’s than wake the proof headphones, Thine behalo’d head rests amidst supernal, drooling DeMilo half not giving a shit ASSOCIatE Sara Kanewske the ruins of your #6 Wen- supine before me. Behold, thine anymore EDITORS Stephen Short dy’s combo, sitting hair adorned in grease and PUBLICITY Sabrina Abdulla Turn-offs: at computer V2 tangles, with spectacles Erica Grundish all askew—be still my waking up beating heart! Sleep with desk Sara Nienkerk soft, my salivating lines on your WRITING staFF Mike Faerber seraphim, whilst I go face, loud typists, Kelsey Lamb swiping your ID after get a Rockstar and Ross Luippold some M&M’s. -

The Reel Latina/O Soldier in American War Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-26-2012 12:00 AM The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema Felipe Q. Quintanilla The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Rafael Montano The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Felipe Q. Quintanilla 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Quintanilla, Felipe Q., "The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 928. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/928 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REEL LATINA/O SOLDIER IN AMERICAN WAR CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Hispanic Studies The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ -

Report by Show Title

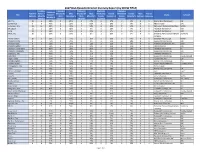

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SHOW TITLE) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined TotAl # of FemAle + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by FemAle Directed by FemAle Male FemAle Title FemAle + Studio Network Episodes Minority Male CaucasiAn % Male Minority % FemAle CaucasiAn % FemAle Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes CaucasiAn Minority CaucasiAn Minority 100, The 12 4 33% 8 67% 2 17% 2 17% 0 0% 0 0 Warner Bros Companies CW 12 Monkeys 8 6 75% 2 25% 5 63% 1 13% 0 0% 0 0 NBC Universal Syfy 13 Reasons Why 13 11 85% 2 15% 7 54% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 Paramount Pictures Corporation Netflix 24: Legacy 11 2 18% 9 82% 0 0% 2 18% 0 0% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX A.P.B. 11 4 36% 7 64% 2 18% 1 9% 1 9% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FOX Affair, The 10 1 10% 9 90% 0 0% 1 10% 0 0% 0 0 Showtime Pictures Development Showtime Company Altered Carbon 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 2 20% 0 0% 0 0 Skydance Pictures, LLC Netflix American Crime 8 6 75% 2 25% 0 0% 2 25% 4 50% 0 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC American Gods 9 2 22% 7 78% 1 11% 1 11% 0 0% 0 0 Fremantle Productions, Inc. Starz! American Gothic 13 7 54% 6 46% 3 23% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0 CBS Companies CBS American Horror Story 10 8 80% 2 20% 2 20% 5 50% 1 10% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX American Housewife 22 8 36% 13 59% 2 9% 5 23% 1 5% 1 0 Disney/ABC Companies ABC Americans, The 13 6 46% 7 54% 2 15% 3 23% 1 8% 0 0 Twentieth Century Fox FX Andi Mack 13 3 23% 10 77% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 1 Disney/ABC Companies Disney Channel Angie Tribeca 10 3 30% 7 70% 1 10% 1 10% 1 10% 0 0 Turner Films, Inc. -

ORANGE IS the NEW BLACK Season 1 Cast List SERIES

ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK Season 1 Cast List SERIES REGULARS PIPER – TAYLOR SCHILLING LARRY BLOOM – JASON BIGGS MISS CLAUDETTE PELAGE – MICHELLE HURST GALINA “RED” REZNIKOV – KATE MULGREW ALEX VAUSE – LAURA PREPON SAM HEALY – MICHAEL HARNEY RECURRING CAST NICKY NICHOLS – NATASHA LYONNE (Episodes 1 – 13) PORNSTACHE MENDEZ – PABLO SCHREIBER (Episodes 1 – 13) DAYANARA DIAZ – DASCHA POLANCO (Episodes 1 – 13) JOHN BENNETT – MATT MCGORRY (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) LORNA MORELLO – YAEL MORELLO (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13) BIG BOO – LEA DELARIA (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) TASHA “TAYSTEE” JEFFERSON – DANIELLE BROOKS (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13) JOSEPH “JOE” CAPUTO – NICK SANDOW (Episodes 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) YOGA JONES – CONSTANCE SHULMAN (Episodes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) GLORIA MENDOZA – SELENIS LEYVA (Episodes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13) S. O’NEILL – JOEL MARSH GARLAND (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13) CRAZY EYES – UZO ADUBA (Episodes 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) POUSSEY – SAMIRA WILEY (Episodes 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13) POLLY HARPER – MARIA DIZZIA (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12) JANAE WATSON – VICKY JEUDY (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) WANDA BELL – CATHERINE CURTIN (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13) LEANNE TAYLOR – EMMA MYLES (Episodes 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) NORMA – ANNIE GOLDEN (Episodes 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13) ALEIDA DIAZ – ELIZABETH RODRIGUEZ