Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belize National Sustainable Development Report

UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report Belize National Sustainable Development Report Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development, Belize United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (UNDESA) United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ____________________________________ INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS – www.idcbz.net Page | 1 UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Acronyms Acknowledgements 1.0. Belize Context……………………………………………………………………………………5 1.1 Geographical Location………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Climate………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.3 Hydrology……………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.4 Population…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.5 Political Context……………………………………………………………………………...7 1.6 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………...7 2.0 Background and Approach………………………………………………………………………….7 3.0 Policy and Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development………………………………8 3.1 National Level………………………………………………………………………………..8 3.2 Multi-Lateral Agreements…………………………………………………………………...9 4.0 Progress to Date in Sustainable Development…………………………………………………..10 5.0 Challenges to Sustainable Development…………………………………………………………23 5.1 Environmental and Social Vulnerabilities………………………………………………..23 5.2 Natural Disasters…………………………………………………………………………...23 5.3 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………….23 5.4 Economic Vulnerability…………………………………………………………………….24 5.5 Policy and Institutional Challenges……………………………………………………….24 6.0 Opportunities for Sustainable Development……………………………………………………..26 -

The Song of Kriol: a Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize

The Song of Kriol: A Grammar of the Kriol Language of Belize Ken Decker THE SONG OF KRIOL: A GRAMMAR OF THE KRIOL LANGUAGE OF BELIZE Ken Decker SIL International DIS DA FI WI LANGWIJ Belize Kriol Project This is a publication of the Belize Kriol Project, the language and literacy arm of the National Kriol Council No part of this publication may be altered, and no part may be reproduced in any form without the express permission of the author or of the Belize Kriol Project, with the exception of brief excerpts in articles or reviews or for educational purposes. Please send any comments to: Ken Decker SIL International 7500 West Camp Wisdom Rd. Dallas, TX 75236 e-mail: [email protected] or Belize Kriol Project P.O. Box 2120 Belize City, Belize c/o e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Copies of this and other publications of the Belize Kriol Project may be obtained through the publisher or the Bible Society Bookstore 33 Central American Blvd. Belize City, Belize e-mail: [email protected] © Belize Kriol Project 2005 ISBN # 978-976-95215-2-0 First Published 2005 2nd Edition 2009 Electronic Edition 2013 CONTENTS 1. LANGUAGE IN BELIZE ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 AN INTRODUCTION TO LANGUAGE ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 DEFINING BELIZE KRIOL AND BELIZE CREOLE ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 -

Supplementary – March 5 2020

BELIZE No. HR35/1/12 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Thursday, 5 th March 2020 10:00 AM * * * S U P P L E M E N T A R Y (1) ORDERS OF THE DAY 6. Papers. No. HR247/1/12 The Nineteenth Annual Report of the Ombudsman of Belize for the Year Ending 2019. No. HR248/1/12 Ministry of Works – Corozal to Sarteneja Road Upgrading Contract No. 183. No. HR249/1/12 Ministry of Works – Sixth Road (Coastal Highway Upgrading) Project Lots 1 and 2 Consultancy Services for Engineering Supervision Phase 2 (Two) Construction and Post Construction Services Contract No. 202. No. HR250/1/12 Ministry of Works – Sixth Road (Coastal Highway Upgrading) Project Lot 1 (One) (La Democracia to Soldier Creek Bridge) Contract No. 203. No. HR251/1/12 Ministry of Works – Sixth Road (Coastal Highway Upgrading) Project Lot 2 (Two) (Soldier Creek Bridge to Coastal Highway/ Hummingbird Highway Junction) Contract No. 204. No. HR252/1/12 Ministry of Works – Caracol Road Upgrading Project Lot1a (Santa Elena To Tripartite Junction and Georgeville to Tripartite Junction) Contract No. 205. No. HR253/1/12 Ministry of Works – Caracol Road Upgrading Project Lot1b (Tripartite Junction to Blancaneaux Lodge Line) Contract No. 206. 2 12. Introduction of Bills. 1. General Revenue Appropriation (2020/2021) Bill, 2020. Bill for an Act to appropriate certain sums of money for the use of the Public Service of Belize for the financial year ending March 31, 2021. 2. Government Contracts (Validation) Bill, 2020. Bill for an Act to validate the omission by the Minister to lay government contracts on the table of both Houses of the National Assembly for examination by each House of the National Assembly, in accordance with section 19(6) of Finance and Audit (Reform) Act, Chapter 15 of the Substantive Laws of Belize, Revised Edition 2011; and to provide for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. -

Belize City in 1 Day 63

CONTENTS List of Maps vi 1 THE BEST OF BELIZE 1 The Best Purely Belizean The Best Destinations for Experiences 1 Families 11 The Best of Natural Belize 4 The Best Luxury Hotels & Resorts 12 The Best Diving & Snorkeling 5 The Best Moderately Priced The Best Nondiving Adventures 6 Hotels 13 The Best Day Hikes & Nature The Best Budget Hotels 14 Walks 7 The Best Restaurants 15 The Best Bird-Watching 8 The Best After-Dark Fun 17 The Best Mayan Ruins 9 The Best Websites About Belize 17 The Best Views 10 2 BELIZE IN DEPTH 19 Belize Today 19 Art & Architecture 26 SPEAKING OF TONGUES 20 Belize in Books, Film & Music 27 Looking Back at Belize 21 Belizean Food & Drink 29 The Lay of the Land 24 3 PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO BELIZE 34 When to Go 34 Specialized Travel Resources 47 BELIZE CALENDAR OF EVENTS 35 Sustainable Tourism 48 Entry Requirements 37 SUSTAINABLE PROPERTIES IN BELIZE 49 Getting There & Getting Around 38 GENERAL RESOURCES FOR GREEN TRAVEL 50 CAR-RENTALCOPYRIGHTED TIPS 41 MATERIAL 51 Money & Costs 42 Staying Connected PLANNING A BELIZE WEDDING 52 Health 44 Tips on Accommodations 53 Safety 46 002_9780470887707-ftoc.indd2_9780470887707-ftoc.indd iiiiii 111/16/101/16/10 66:14:14 PPMM 4 SUGGESTED BELIZE ITINERARIES 54 The Regions in Brief 54 Belize for Families 60 Belize in 1 Week 57 Mayan Ruins Highlights 62 Belize in 2 Weeks 58 Belize City in 1 Day 63 5 THE ACTIVE VACATION PLANNER 65 Organized Adventure Trips 65 Tips on Health, Safety & Etiquette Activities A to Z 68 in the Wilderness 79 Belize’s Top Parks & Bioreserves 75 Ecologically Oriented -

Itinerary & Program

Overview Explore Belize in Central America in all of its natural beauty while embarking on incredible tropical adventures. Over nine days, this tour will explore beautiful rainforests, Mayan ruins and archeology, and islands of this tropical paradise. Some highlights include an amazing tour of the Actun Tunichil Muknal (“Cave of the Crystal Maiden”), also known at ATM cave; snorkeling the second largest barrier reef in the world, the critically endangered Mesoamerican Barrier Reef, at the tropical paradise of South Water Caye; touring Xunantunich Mayan ruin (“Sculpture of Lady”); and enjoying a boat ride on the New River to the remote Mayan village of Lamanai. Throughout this tour, we’ll have the expertise of Luis Godoy from Belize Nature Travel, a native Mayan and one of Belize’s premier licensed guides, to lead us on some amazing excursions and share in Belize’s heritage. We’ll also stay at locally owned hotels and resorts and dine at local restaurants so we can truly experience the warm and welcoming culture of Belize. UWSP Adventure Tours leaders Sue and Don Kissinger are ready to return to Belize to share the many experiences and adventures they’ve had in this beautiful country over the years. If you ask Sue if this is the perfect adventure travel opportunity for you she’ll say, “If you have an adventurous spirit, YOU BETTER BELIZE IT!” Tour Leaders Sue and Don Kissinger Sue and Don have travelled extensively throughout the United States, Canada, Central America, Africa and Europe. They met 36 years ago as UW-Stevens Point students on an international trip and just celebrated their 34th wedding anniversary. -

Private Lands Conservation in Belize

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Books, Reports, and Studies Resources, Energy, and the Environment 2004 Private Lands Conservation in Belize Joan Marsan University of Colorado Boulder. Natural Resources Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/books_reports_studies Part of the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons, Environmental Law Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Estates and Trusts Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Legislation Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Property Law and Real Estate Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Citation Information Joan Marsan, Private Lands Conservation In Belize (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch. of Law 2004). JOAN MARSAN, PRIVATE LANDS CONSERVATION IN BELIZE (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch. of Law 2004). Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. AVAILABLE ONLINE ====================; • •~ ~ ...... ~ ~ ~ .~ PRIVATE LANDS CONSERVATION IN .~ BELIZE •_. -~ • ~ .. A Country Report by the Natural Resources Law Center, ...... University of Colorado School of Law ~ 4 .~ September 2004 ~ Sponsored by The Nature Conservancy Primary Author: Joan Marsan, NRLC Research Assistant KGA [email protected] 576 • M37 2004 Private Lands -

General Assembly Distr

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/WG.6/5/BLZ/1 18 February 2009 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Fifth session Geneva, 4-15 May 2009 NATIONAL REPORT SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH PARAGRAPH 15 (A) OF THE ANNEX TO HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL RESOLUTION 5/1 * Belize _________________________ * The present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.09- A/HRC/WG.6/5/BLZ/1 Page 2 I. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY 1. Belize is firmly committed to the protection and promotion of human rights as evidenced by its Constitution, domestic legislation, adherence to international treaties and existing national agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). 2. Belizean culture, democratic history and legal tradition has infused in Belizean society and government a deep respect for those fundamental human rights articulated in Part II of the Belize Constitution. Such fundamental freedoms as the right to assembly, the right to free speech and the right to due process are vigilantly guarded by Belizeans themselves. 3. As a developing country Belize views development as inextricably bound to the fulfilment of human rights making the right to development a fundamental right itself as asserted by the Declaration on the Right to Development. Thus, the Government of Belize has consistently adopted a human rights based approach in development planning, social services and general policy formulation and execution. 4. Belize’s national report for the Universal Periodic Review has been prepared in accordance with the General Guidelines for the Preparation of Information under the Universal Periodic Review, decision 6/102, as circulated adopted by the Human Rights Council on 27 September 2007. -

The Place of Ata in Belizean Kriol

Encoding Contrast, Inviting Disapproval: The Place of Ata in Belizean Kriol WILLIAM SALMON University of Minnesota, Duluth1 1 Introduction This paper investigates the semantics and pragmatics of the discourse marker ata in Belizean Kriol, as seen in (1). I show that ata is an adversative discourse marker similar to the Spanish discourse marker si, as described in Schwenter (1999, 2002), and that the two share much in terms of syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. This is interesting, as there seems to be no English counterpart to the Kriol ata or Spanish si. (1) A: Wai yu nak yu sista?2 B: Ata da shee nak me fos! [KID] A: Why did you hit your sister? B: (But) it was she who hit me first!3 In terms of ata, I argue that it is used to convey an emphatic contrast with the immediately preceding discourse and that this contrast is a conventional implicature of the type described in Grice (1975). In addition, it is frequently used in conveying negative attitudes toward the preceding discourse. I argue that this is not a conventional aspect of ata’s meaning but that it is instead calculated in context via Gricean pragmatic reasoning as a conversational implicature. Finally, I suggest a diachronic origin for ata in the Kriol focus marker da. This present account of ata, then, covers significantly different ground than the account given in Salmon (to appear). In the next section, which follows from Salmon (to appear), I provide a brief background on the Kriol language as well as a discussion of where and how the data used in this paper were collected. -

LIST of REMITTANCE SERVICE PROVIDERS Belize Chamber Of

LIST OF REMITTANCE SERVICE PROVIDERS Name of Remittance Service Providers Addresses Belize Chamber of Commerce and Industry Belize Chamber of Commerce and Industry 4792 Coney Drive, Belize City Agents Amrapurs Belize Corozal Road, Orange Walk Town BJET's Financial Services Limited 94 Commerce Street, Dangriga Town, Stann Creek District, Belize Business Box Ecumenical Drive, Dangriga Town Caribbean Spa Services Placencia Village, Stann Creek District, Belize Casa Café 46 Forest Drive, Belmopan City, Cayo District Charlton's Cable 9 George Price Street, Punta Gorda Town, Toledo District Charlton's Cable Bella Vista, Toledo District Diversified Life Solutions 39 Albert Street West, Belize City Doony’s 57 Albert Street, Belize City Doony's Instant Loan Ltd. 8 Park Street South, Corozal District Ecabucks 15 Corner George and Orange Street, Belize City Ecabucks (X-treme Geeks, San Pedro) Corner Pescador Drive and Caribena Street, San Pedro Town, Ambergris Caye EMJ's Jewelry Placencia Village, Stann Creek District, Belize Escalante's Service Station Co. Ltd. Savannah Road, Independence Village Havana Pharmacy 22 Havana Street, Dangriga Town Hotel Coastal Bay Pescador Drive, San Pedro Town i Signature Designs 42 George Price Highway, Santa Elena Town, Cayo District Joyful Inn 49 Main Middle Street, Punta Gorda Town Landy's And Sons 141 Belize Corozal Road, Orange Walk Town Low's Supermarket Mile 8 ½ Philip Goldson Highway, Ladyville Village, Belize District Mahung’s Corner North/Main Streets, Punta Gorda Town Medical Health Supplies Pharmacy 1 Street South, Corozal Town Misericordia De Dios 27 Guadalupe Street, Orange Walk Town Paz Villas Pescador Drive, San Pedro Town Pomona Service Center Ltd. -

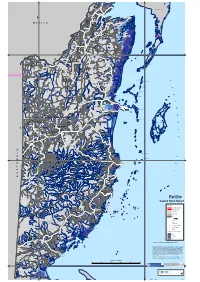

Coastal Flood Hazard M E X I C O G U a T E M A

!( Santa Elena !( Consejo Chan Chen !( M E X I C O Estero !( Paraiso !( San Antonio !( !(Santa Rita !( Xcanluum !( Patchakan Altamira San Andres!( !( !. !( Laguna!( Tacistal !( Corozal Xaibe !( Carolina !( Ranchito Yo Chen Calcutta!( Sarteneja !( !( San Joaquin!( !( !( Cristo Rey San Maximo !( San Pedro !(Aventura Concepcion Copper Bank!( Louisville !( !( !( San Fransisco !( Saltillo San Narciso !( !( !( Libertad Pueblo Nuevo !( !( M E X I C O San Roman !( Chunox !( Estrella Santa Clara !( Benque Viejo San Victor San Jose Nuevo !( !( !( Santa Cruz Hill Bank Douglas !( !( !( !( San Juan Buena Vista !( Progresso !( Caledonia !( Little Belize !( San Pablo !( Fireburn !( !( !( San Roman San Luis San Jose San Estevan !( C O R O Z A L !( San Antonio !( San Lorenzo !( Santa Cruz !( Trial Farm Yo Creek !( Orange Walk Town!. San Jose Palmar !( San Lazaro !( !( !( Chan Pine Ridge Tower Hill Trinidad!( !(Carmelita !( !(Santa Martha August Pine Ridge !( Guinea Grass Edenthal !( !( Quatros Leguas !. !( Shipyard San Pedro !( Neuendorf Neustadt !( Bomba !( !( !( Tres Leguas !( !( Dos Bocas Blue Creek !( Rosita !( Nag o Ban k !( Maskall Reinland !( San Felipe !( !( Gangrejo Caye Fire Burn Rhaburn Ridge St. Anns!( !( !( Corozalito Backlanding La Milpa Chicago !( !( !( Santana Crooked Tree !( !( Lucky Strike C !( Cowhead Caye Caulker !( !( !( Creek Indian Church Rockstone Pond Caye Caulker San Carlos !( Biscayne !( Caye Chapel A !( Gardenia !( Boston May Pen O R A N G E W A L K !( Long Caye !( Davis/ Grace Bank !( Sand Hill R Flowers Bank Maxboro !( !( !( Hill Bank!( Lemonal Hicks Caye !( Isabella Bank Gentleville Sylvester !( !( Los Lagos !( !( I !( Burrel Boom St. George's Caye Gallon Jug !( Bermudian Landing !( !( Scotland Halfmoon !( Fresh Pond Lord's Bank Ladyville !( !( Double Head Cabbage !( !(Chan Chich !( Ramon's Village !( Vista Del Mar !( !(Willows Bank Rancho Dolores St. -

Belize BELIZE

Belize BELIZE In 2012, Belize made a moderate advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. The Government enacted a new Trafficking in Persons law, which increases the penalties for offenders to up to 12 years’ imprisonment if the victim is a child. The Government also enacted the Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children Act, which provides all children under the age of 18 with protections from such criminal offenses. The Government, in collaboration with UNICEF, released the results of the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), quantifying, among other social indicators, the prevalence of child labor within the country. It continues to implement the National Child Labor Policy and programs such as Building Opportunities for Our Social Transformation (BOOST) that focus on poverty alleviation and promote education. Despite these advancements, Belize has not formally adopted a list of hazardous occupations, and labor inspectors still lack the resources to enforce child labor laws adequately. Children in Belize continue to engage in the worst forms of child labor, including in dangerous activities within the agricultural sector and commercial sexual exploitation. Children in Belize are also victims of commercial sexual Statistics on Working Children and Education exploitation and forced prostitution.(3, 5, 10) Limited Children Age Percent evidence suggests that some poor families, in an effort to cover schooling and basic living expenses, push their daughters to Working 5-14 yrs. Unavailable provide sexual favors in exchange for gifts and money.(5) Child sex tourism is also a problem in Belize. Children are trafficked Attending School 5-14 yrs. Unavailable into the country for sexual exploitation.(3, 5, 10-12) Combining Work and School 7-14 yrs. -

Orthography Development for Creole Languages Decker, Ken

University of Groningen Orthography Development for Creole Languages Decker, Ken IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2014 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Decker, K. (2014). Orthography Development for Creole Languages. [S.n.]. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 01-10-2021 ORTHOGRAPHY DEVELOPMENT FOR CREOLE LANGUAGES KENDALL DON DECKER The work in this thesis has been carried out under the auspices of SIL International® in collaboration with the National Kriol Council of Belize.