Affective Timelines Towards the Primary-Process Emotions Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Saw 3 1080P Dual

Saw 3 1080p dual click here to download Saw III UnRated English Movie p 6CH & p Saw III full movie hindi p dual audio download Quality: p | p Bluray. Saw III UnRated English Movie p 6CH & p BluRay-Direct Links. Download Saw part 3 full movie on ExtraMovies Genre: Crime | Horror | Exciting. Saw III () Saw III P TORRENT Saw III P TORRENT Saw III [DVDRip] [Spanish] [Ac3 ] [Dual Spa-Eng], Gigabyte, 3, 1. Download Saw III p p Movie Download hd popcorns, Direct download p p high quality movies just in single click from HDPopcorns. Jeff is an anguished man, who grieves and misses his young son that was killed by a driver in a car accident. He has become obsessed for. saw dual audio p movies free Download Link . 2 saw 2 mkv dual audio full movie free download, Keyword 3 saw 2 mkv dual audio full movie free. Our Site. IMDB: / MPA: R. Language: English. Available in: p I p. Download Saw 3 Full HD Movie p Free High Quality with Single Click High Speed Downloading Platform. Saw III () BRRip p Latino/Ingles Nuevas y macabras aventuras Richard La Cigueña () BRRIP HD p Dual Latino / Ingles. Horror · Jigsaw kidnaps a doctor named to keep him alive while he watches his new apprentice Videos. Saw III -- Trailer for the third installment in this horror film series. Saw III 27 Oct Descargar Saw 3 HD p Latino – Nuevas y macabras aventuras del siniestro Jigsaw, Audio: Español Latino e Inglés Sub (Dual). Saw III () UnRated p BluRay English mb | Language ; The Gravedancers p UnRated BRRip Dual Audio by. -

Jigsaw: Torture Porn Rebooted? Steve Jones After a Seven-Year Hiatus

Originally published in: Bacon, S. (ed.) Horror: A Companion. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2019. This version © Steve Jones 2018 Jigsaw: Torture Porn Rebooted? Steve Jones After a seven-year hiatus, ‘just when you thought it was safe to go back to the cinema for Halloween’ (Croot 2017), the Saw franchise returned. Critics overwhelming disapproved of franchise’s reinvigoration, and much of that dissention centred around a label that is synonymous with Saw: ‘torture porn’. Numerous critics pegged the original Saw (2004) as torture porn’s prototype (see Lidz 2009, Canberra Times 2008). Accordingly, critics such as Lee (2017) characterised Jigsaw’s release as heralding an unwelcome ‘torture porn comeback’. This chapter will investigate the legitimacy of this concern in order to determine what ‘torture porn’ is and means in the Jigsaw era. ‘Torture porn’ originates in press discourse. The term was coined by David Edelstein (2006), but its implied meanings were entrenched by its proliferation within journalistic film criticism (for a detailed discussion of the label’s development and its implied meanings, see Jones 2013). On examining the films brought together within the press discourse, it becomes apparent that ‘torture porn’ is applied to narratives made after 2003 that centralise abduction, imprisonment, and torture. These films focus on protagonists’ fear and/or pain, encoding the latter in a manner that seeks to ‘inspire trepidation, tension, or revulsion for the audience’ (Jones 2013, 8). The press discourse was not principally designed to delineate a subgenre however. Rather, it allowed critics to disparage popular horror movies. Torture porn films – according to their detractors – are comprised of violence without sufficient narrative or character development (see McCartney 2007, Slotek 2009). -

Darrenmcfarlane(2018CV)

Darren McFarlane 34 Riddell Parade Profile Elsternwick, VIC 3185 M 0412 948 183 From a PhD in Polymer Chemistry to working on TVC’s, Australian and US features, [email protected] Australian Drama, and to then being approached by Leigh Whannell and James Wan to produce a short film version of their feature script, “Saw” - a highly experienced production person with a great breadth of credits, enthusiasm for challenges, strong work ethic, a positive ‘can do’ attitude and a sense of humour. Features Line Producer - “High Ground”, High Ground Pictures - 2018 Directed by Stephen Johnson. Produced by David Jowsey, Greer Simpkin & Maggie Miles. Line Producer - “Brothers’ Nest”, Jason Byrne Productions - 2017 Directed by Clayton Jacobson. Produced by Jason Byrne. Production Manager - “Guilty”, ABC Co Production - 2017 Directed by Matthew Sleet. Produced by Maggie Miles. Construction Co-ordinator - “The Moon and the Sun”, Lightstream Films - 2014 Produced by Paul Currie and Bill Mechanic. Production Assistant - “Charlotte’s Web”, Paramount Pictures - 2005 Directed by Gary Winick and produced by Jordan Kerner. Additional AD - “The Extra”, Ruby Entertainment - 2005 Directed by Kev Carlin and produced by Stephen Luby and Mark Ruse. Additional AD - “Three Dollars”, Arenafilm - 2005 Directed by Rob Connolly and produced by John Maynard. Dance Club/Rave Scene Producer - “One Perfect Day”, Lightstream Films - 2004 Directed by Paul Currie and produced by Charles Morton. TV Series Producer - “Seconds”, Head Space Entertainment - 2019 Director Tony Rogers, Writer Jaime Brown (6 x 60 min episodes) - In Development. Production Manager - “Superwog”, ABC/Princess Pictures - 2018 Produced by Paul Walton & Amanda Reedy (6 x 30 min episodes). -

Nouveautés Mai 2021

NOUVEAUTÉS MAI 2021 "Titre" © production "Titre" © production "Titre" © production "Titre" © production "Titre" © production "Titre" © production "Sankara n'est pas mort" © Les Films du Bilboquet ; " Jumbo" © Insolence Prod.; " Bad education" © Automatik ; " The secret garden " © STX Films ; " Mine 9 " © Autumn Bailey Entertainement ; " Waiting for the barbarians " © Iervolino Entertainment 1 Berlin in naher Zukunft: Nach einem wirtschaftlichen und gesellschaftlichen FILMS Zusammenbruch regiert auf den Straßen der Stadt die Gesetzlosigkeit. Die zwei Freunde Tan und Javid sind abtrünnige Geächtete auf der Suche nach dem D’ACTION Mann, der ihre Familien getötet hat. Bei einer Schießerei in einem Kebap-Laden töten Tan und Eagle eye = Eagle eye : ausser Javid versehentlich die Eltern der jungen Studentin Eliana und sind fortan Ziel einer Vendetta. Die Kontrolle beiden Freunde haben keine Ahnung was ihnen bevorsteht, bis sie eines Tages ein mysteriöses Eagle eye = Eagle eye : ausser Kontrolle Drehbuch finden, in dem ihre eigene Geschichte Jerry and Rachel are two strangers thrown together erzählt wird. Es ist das Drehbuch zu einem Film by a mysterious phone call from a woman they have namens „Schneeflöckchen“. Egal was Tan und never met. Threatening their lives and family, she Javid machen, alles passiert genau so, wie es pushes Jerry and Rachel into a series of geschrieben steht. Und so versuchen sie increasingly dangerous situations, using the verzweifelt, aus der Handlung auszubrechen, die sie technology of everyday life to track and control their auf einen katastrophalen Höhepunkt bringt. every move. 1 DVD vidéo (ca 116 min.) Cote: ACT KOLs 1 DVD (ca 113 min.) Cote: ACT CARe Breaking surface = Breaking Mine 9 surface : tödliche Tiefe written and dir. -

UNIVERSAL PICTURES Presents a BLUMHOUSE/GOALPOST

UNIVERSAL PICTURES Presents A BLUMHOUSE/GOALPOST Production In Association with NERVOUS TICK PRODUCTIONS ELISABETH MOSS ALDIS HODGE STORM REID HARRIET DYER MICHAEL DORMAN and OLIVER JACKSON-COHEN Executive Producers LEIGH WHANNEL COUPER SAMUELSON BEATRIZ SEQUEIRA JEANETTE VOLTURNO ROSEMARY BLIGHT BEN GRANT Produced by JASON BLUM, p.g.a. KYLIE DU FRESNE, p.g.a. Screenplay and Screen Story by LEIGH WHANNELL Directed by LEIGH WHANNELL The Invisible Man_Production Information 2 PRODUCTION INFORMATION What you can’t see can hurt you. Emmy Award winner ELISABETH MOSS (Us, Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale) stars in a terrifying modern tale of obsession inspired by Universal’s classic Monster character. Trapped in a violent, controlling relationship with a wealthy and brilliant scientist, Cecilia Kass (Moss) escapes in the dead of night and disappears into hiding, aided by her sister Emily (HARRIET DYER, NBC’s The InBetween), their childhood friend James (ALDIS HODGE, Straight Outta Compton) and his teenage daughter Sydney (STORM REID, HBO’s Euphoria). But when Cecilia’s abusive ex, Adrian (OLIVER JACKSON-COHEN, Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House), commits suicide and leaves her a generous portion of his vast fortune, Cecilia suspects his death was a hoax. As a series of eerie coincidences turn lethal, threatening the lives of those she loves, Cecilia’s sanity begins to unravel as she desperately tries to prove that she is being hunted by someone nobody can see. JASON BLUM produces The Invisible Man for Blumhouse Productions. The Invisible Man is written, directed and executive produced by LEIGH WHANNELL, one of the original conceivers of the Saw franchise who most recently directed Upgrade and Insidious: Chapter 3. -

VICE Studios and Screen Australia Present in Association with Film Victoria and Create NSW a Blue-Tongue Films and Pariah Production

VICE Studios and Screen Australia present In association with Film Victoria and Create NSW A Blue-Tongue Films and Pariah Production Written and Directed by Mirrah Foulkes Starring Mia Wasikowska and Damon Herriman Produced by Michele Bennett, Nash Edgerton and Danny Gabai Run Time: 105 Minutes Press Contact Samuel Goldwyn Films [email protected] SYNOPSES Short Synopsis In the anarchic town of Seaside, nowhere near the sea, puppeteers Judy and Punch are trying to resurrect their marionette show. The show is a hit due to Judy's superior puppeteering, but Punch's driving ambition and penchant for whisky lead to an inevitable tragedy that Judy must avenge. Long Synopsis In the anarchic town of Seaside, nowhere near the sea, puppeteers Judy and Punch are trying to resurrect their marionette show. The show is a hit due to Judy's superior puppeteering, but Punch's driving ambition and penchant for whisky lead to an inevitable tragedy that Judy must avenge. In a visceral and dynamic live-action reinterpretation of the famous 16th century puppet show, writer director MIRRAH FOULKES turns the traditional story of Punch and Judy on its head and brings to life a fierce, darkly comic and epic female-driven revenge story, starring MIA WASIKOWSKA and DAMON HERRIMAN. 2 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT JUDY AND PUNCH is a dark, absurd fable treading a line between fairy-tale, fantasy and gritty realism, all of which work together to establish a unique tone while upsetting viewer expectations. When Vice Studios’ Eddy Moretti and Danny Gabai approached me with the idea of making a live action, feminist revenge film about Punch and Judy, they encouraged me to let my imagination go wild and take the story wherever I felt it needed to go. -

Guide Des Personnes Et Des Films Concourant Pour Les César 2019 Ce Guide Recense Les Personnes Et Les Films Concourant Pour Les César 2019

Académie des Arts et Techniques du Cinéma GUIDE FILMS CÉSAR 2019 GUIDE DES PERSONNES ET DES FILMS CONCOURANT POUR LES CÉSAR 2019 Ce guide recense les personnes et les films concourant pour les César 2019. Toutes les informations contenues dans ce guide sont compilées à partir des documents édités par les dispositifs grand public de référencement cinéma, les sociétés de production, et le CNC. Elles n’ont comme seul objet que de faciliter le vote des membres de l’Académie. L’APC fait ses meilleurs efforts pour en vérifier l’exactitude, mais ne pourra en aucun cas être tenue responsable des éventuelles informations inexactes contenues dans ce guide. www.academie-cinema.org [email protected] SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE FICHES DE PRÉSENTATION DES FILMS CONCOURANT POUR LE CÉSAR DU MEILLEUR FILM ET POUR LES AUTRES CATÉGORIES DE CÉSAR (comprenant pour chaque film la liste des personnes y ayant collaboré et concourant à ce titre pour les César attribués à des personnes) p. 3 à 118 FICHES DE PRÉSENTATION DES FILMS d’expression originale française ET DE PRODUCTION FRANÇAISE MINORITAIRE CONCOURANT POUR LE CÉSAR DU MEILLEUR FILM ÉTRANGER (comprenant pour chaque film la liste des personnes y ayant collaboré et concourant à ce titre pour les César attribués à des personnes) p. 119 à 124 LISTE DES FILMS CONCOURANT POUR LE CÉSAR DU MEILLEUR FILM ÉTRANGER p. 125 à 139 FICHES DE PRÉSENTATION DES FILMS CONCOURANT POUR LE CÉSAR DU MEILLEUR Film d’ANIMATION POUR LE LONG MÉTRAGE ET POUR LE COURT MÉTRAGE p. 141 à 149 FICHES DE PRÉSENTATION DES FILMS CONCOURANT POUR LE CÉSAR DU MEILLEUR FILM DE COURT MÉTRAGE p. -

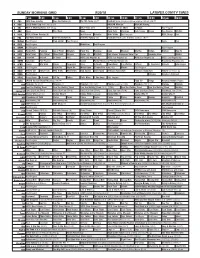

Sunday Morning Grid 9/30/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/30/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Miami Dolphins at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC 2018 Ryder Cup Final Day. (3) (N) NASCAR Monster NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Vacation Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Detroit Lions at Dallas Cowboys. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Kitchen How To 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Rick Steves’ European Travel Tips Concrete River Mathis 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

The Problem of Saw Torture Porn | Horror Films | Irony

32 SAW ARTICLE 11/4/09 8:53 PM Page 32 The Problem of Saw: “Torture Porn” and the Conservatism of Contemporary Horror Films by Christopher Sharrett he Saw films initiated in 2003 by a woman shoved into a pit of syringes; a Lewton, Terence Fisher, William Castle, and James Wan and Leigh Whannell rep- woman decapitated by shotgun blasts) to the Roger Corman, among others. The Sixties T resent the most lucrative horror fran- near-total exclusion of context, aside from saw the emergence of the horror genre as chise of the new century, and, with Eli outright absurd ruminations about the vil- subversive form, an impulse well chronicled Roth’s two Hostel films (released in 2006 lain’s motivations. The consequences of vio- by Robin Wood in his pivotal, much- and 2007), figure as the most prominent lence for the individual and society, for all anthologized essay, “An Introduction to the examples of a reactionary tendency of the the bogus moralizing of these films, is American Horror Film.” Hitchcock’s Psycho genre as it descends into what is popularly nowhere in evidence. Indeed, if Saw is an (1960) and The Birds (1963), Polanski’s known as “torture porn,” a form alarming indicator, the lessons about screen violence Rosemary’s Baby (1968), and George in its diminishing of the genre, and its disre- taught by Penn, Peckinpah, Aldrich, Siegel, Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) gard of the psychological content and social Scorsese, or master horror directors such as established the genre as keenly critical of criticism of the horror middle-class life and all film at its height (al- its supporting institu- though Saw and its tions, particularly the sequels try mightily to The latest fashion in fear or politically patriarchal nuclear fami- mask their intellectual toxic mortality tales? Make your choice. -

CYBORG MIND What Brain–Computer And

CYBORG MIND What Brain‒Computer and Mind‒Cyberspace Interfaces Mean for Cyberneuroethics CYBORG MIND Edited by Calum MacKellar Offers a valuable contribution to a conversation that promises to only grow in relevance and importance in the years ahead. Matthew James, St Mary’s University, London ith the development of new direct interfaces between the human brain and comput- Wer systems, the time has come for an in-depth ethical examination of the way these neuronal interfaces may support an interaction between the mind and cyberspace. In so doing, this book does not hesitate to blend disciplines including neurobiology, philosophy, anthropology and politics. It also invites society, as a whole, to seek a path in the use of these interfaces enabling humanity to prosper while avoiding the relevant risks. As such, the volume is the fi rst extensive study in cyberneuroethics, a subject matter which is certain to have a signifi cant impact in the twenty-fi rst century and beyond. Calum MacKellar is Director of Research of the Scottish Council on Human Bioethics, Ed- MACKELLAR inburgh, and Visiting Lecturer of Bioethics at St. Mary’s University, London. His past books EDITED BY What include (as co-editor) The Ethics of the New Eugenics (Berghahn Books, 2014). Brain‒Computer and Mind‒Cyberspace Interfaces Mean for Cyberneuroethics MEDICAL ANTHROPOLOGY EDITED BY CALUM MACKELLAR berghahn N E W Y O R K • O X F O R D Cover image by www.berghahnbooks.com Alexey Kuzin © 123RF.COM Cyborg Mind This open access edition has been made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license thanks to the support of Knowledge Unlatched. -

ABOUT the PRODUCTION One Day Spectrevision Producer Josh Waller Found Himself Chatting with His Niece When the Subject of Cooties Came Up

COOTIES LOGLINE When a chicken nugget virus transforms grade school kids into blood-thirsty savages, oddball teachers trapped inside the building band together to flee the playground carnage. SYNOPSIS Struggling writer Clint Hadson (ELIJAH WOOD) turns up for his first day on the job as a substitute teacher at Ft. Chicken Elementary expecting to find a stress-free gig that allows plenty of time to finish his haunted boat thriller Keel Them All. It gets even better when Clint discovers his adorable former classmate Lucy McCormick (ALISON PILL) teaches at the school, as does her snarky jock boyfriend Wade Johnson (RAINN WILSON). The bad news: unbeknownst to Clint, one of his students ate a contaminated chicken nugget at the local fast food franchise. Her face covered in sores, “Patient Zero” scratches classroom bullies and within minutes, the entire playground has turned into a bloodbath as zombie-like child killers rip every adult they can find from limb to limb. Once the kids turn off the power and dismember Vice-Principal Simms (IAN BRENNAN), Clint, Lucy and Wade band together with goofy art instructor Tracy Simmons (JACK MCBRAYER), mildly schizophrenic science nerd Doug (LEIGH WHANNELL) and right wing disciplinarian Rebekkah Halverson (NASIM PEDRAD) to figure out a survival plan. Unable to call for help because of the school's no-cellphones policy, the embattled faculty members fight their way through a herd of vicious child tormenters and make their getaway with a little help from a pharmaceutically-altered crossing guard (JORGÉ GARCIA). By nightfall, they learn the rest of their small Illinois town has also been terrorized by infected children.