Multisectoral Value Chain Analysis 'Connecting Central America'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sugar Reduction: Report on Progress Between 2015 and 2019

Sugar reduction Report on progress between 2015 and 2019 October 2020 Sugar reduction: report on progress between 2015 and 2019 About Public Health England Public Health England exists to protect and improve the nation’s health and wellbeing and reduce health inequalities. We do this through world-leading science, research, knowledge and intelligence, advocacy, partnerships and the delivery of specialist public health services. We are an executive agency of the Department of Health and Social Care, and a distinct delivery organisation with operational autonomy. We provide government, local government, the NHS, Parliament, industry and the public with evidence-based professional, scientific and delivery expertise and support. Public Health England Wellington House 133-155 Waterloo Road London SE1 8UG Tel: 020 7654 8000 www.gov.uk/phe Twitter: @PHE_uk Facebook: www.facebook.com/PublicHealthEngland Prepared by: Nick Coyle, Emma Little, Sarah Williamson, Sakhi Dodhia, Victoria Targett, Samantha Montel, Paul Niblett, Adele Mildon, Kate Hutchinson, Gabrielle Owtram, Dr Alison Tedstone, and others at PHE For queries relating to this document, please contact: [email protected] © Crown copyright 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence, visit OGL. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Published April 2021 PHE -

European Fruit Juice Association

17-18 October 2018 The must attend event for fruit juice executives www.juicesummit.org AIJN European Fruit Juice Association 2018 Liquid Fruit Market Report AIJN2018_Cover.indd 3 02/08/2018 13:49 AIJN2018_Contents.indd 2 02/08/2018 13:28 Contents COUNTRY PROFILES Austria ........................................................................... 18 Belgium ......................................................................... 19 Bulgaria ......................................................................... 28 Croatia ........................................................................... 28 Cyprus ........................................................................... 28 Czech Republic ................................................................ 30 5 Introduction: Denmark ........................................................................ 30 AIJN President José Jordão Estonia .......................................................................... 30 Finland .......................................................................... 32 6 The Fruit Juice Industry: France ........................................................................... 20 Germany ........................................................................ 21 Overall Fruit Juice and Nectars Consumption Greece ........................................................................... 32 Hungary ......................................................................... 32 7 European Industry Trends and Segmentation Ireland .......................................................................... -

Cultural Innovation: Triumph of a Better Ideology’ Look to Anthropology for Inspiration

QUARTER 1 JANUARY 2012 NEW THINKING, DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES Cultural innovation: triumph of a better ideology Douglas Holt and Douglas Cameron NEVER WASTE A GOOD CRISIS Sir Terry Leahy QUARTER 1 QUARTER 2012 JANUARY ACCOUNTABILITY IS NOT ENOUGH Rory Sutherland THROUGH THE GLASS CEILING Janet Hull 1 cover.indd 1 28/11/2011 19:34:31 Market Leader_Experienica.HR.pdf 1 11/11/2011 13:05 Editorial Keeping brands healthy i rEcEntly attended a lecture on the applications of neuroscience to marketing. All the data marketers will ever need, it was claimed, can now be obtained from ‘neurometrics’ – via MRI scanning, EEG measurement and eye-tracking devices. I listened to the lengthening list of uses with mounting disquiet and an article formed in my mind entitled ‘Caution: neuroscience may be dangerous to the health of your brand’. The lead article in this issue provides the explanation of why the skills required for brand building live in a parallel universe. Douglas Holt and Douglas Cameron in ‘Cultural innovation: triumph of a better ideology’ look to anthropology for inspiration. It is commonplace to say that brands live in the mind (as opposed to the factory). But where they really live is in culture, in society’s norms, values, codes and practices. And while yes, neuroscience and anthropology can exist together, the danger is in what we qualitative researchers call ‘physics envy’ (the need to elevate market research to the level of the pure sciences). Put access to the brain – the human version of the Rosetta Stone – together with lots of gadgetry that measures things and before you know it, the new and intriguing drives out the old but essential. -

Thirst for Innovation

QUENCH YOUR THIRST FOR INNOVATION In a market like this, you need to operate at peak performance. Beverage processors need every advantage they can get. Today, your biggest opportunity lies in innovation. At the Worldwide Food Expo, you’ll see how new technologies can address today’s hot topics — from trends and ingredients to food safety, sustainability and how to “green” your operations and packaging. This is the one event that encompasses the entire dairy, food and beverage production process from beginning to end. So go ahead, quench your thirst and better your bottomline. WHERE THE DAIRY AND FOOD INDUSTRY COME TOGETHER OCTOBER 28–31, 2009 CHICAGO, ILLINOIS McCORMICK PLACE WWW.WORLDWIDEFOOD.COM MOVING AT THE SPEED OF INNOVATION REGISTER TODAY! USE PRIORITY CODE ASD08 Soft Drinks Internationa l – October 2009 ConTEnTS 1 news Europe 4 Africa 6 Middle East 8 The leading English language magazine published in Europe, devoted exclusively to the Asia Pacific 10 manufacture, distribution and marketing of soft drinks, fruit juices and bottled water. Americas 12 Ingredients 14 features Juices & Juice Drinks 18 Energy & Sports 20 Drinks With Attitude 26 The energy drinks caTegory conTinues Waters & Water Plus Drinks 22 To grow and boosTed by The inTroduc - Carbonates 23 Tion of innovaTion such as The energy shoT. Rob Walker gives his analysis. Building A Green Employment Brand 36 Packaging 46 User Friendly Fortification RecruiTing and reTaining like-minded Environment 48 employees can pay dividends, reporTs 28 MargueriTe GranaT. People On-Trend, producT innovaTion has 50 been made easier, according To Events 51 Glanbia NuTriTionals. Sincerity 38 Jo Jacobius Takes a look aT boTTled Bubbling Up 53 waTer producers who Truly Take Meeting The Challenge 30 environmenTal and susTainabiliTy Choosing The righT sweeTener sysTem issues To hearT. -

Offer and Price Products Buy One Get One Free Doritos All Varieties 150G, Doritos Dip All Varieties 300G, Volvic Touch of Fruit

Offer and Price Products Doritos All Varieties 150g, Doritos Dip All Varieties 300g, Volvic Touch of Fruit Strawberry 1.5l, Volvic Touch of Fruit Lemon & Lime 1.5l, Volvic Touch of Summer Fruits 1.5l, Cadbury Dairy Milk Oreo 120g, Cadbury Dairy Milk 110g, Cadbury Dairy Milk Wholenut 120g, Cadbury Dairy Milk Fruit & Nut 120g, Cadbury Dairy Milk Buy One Get One Free Caramel 120g, Cadbury Darkmilk 85g, Starburst Original 210g, Skittles Fruits 196g, Skittles Fruits Giants 170g, Skittles Giant Sours Pouch 170g, Skittles Fruits White Pouch 196g, Haribo Starmix 190g Haribo Tangfastics 190g, Haribo Giant Strawbs 190g, Haribo Super Mix 190g, Maoam Strips 170g Kelllogg’s Cornflakes 450g, Kellogg’s Coco Pops 375g, Kellogg’s Kellogg's and Pringles 2 for £4 Crunchy Nut 375g, Kellogg’s Rice Krispies 375g, Kellogg’s Krave 375g, Pringles All Varieties 200g Lucozade Zero Sugar Tropical 500ml, Lucozade Zero Pink Lucozade 2 for £2 Lemonade 500ml, Lucozade Revive Lemon & Lime 380ml, Lucozade Revive Orange & Passion Fruit 380ml Buxton 2 for £2 Buxton 75cl Mars Duo 78.8g, Snickers Duo 83.4g, Twix Xtra 75g, Twix White Xtra 75g, Snickers Crisp Trio 60g, Twix Salted Caramel Xtra 75g, Mars Duo 2 for £1.50 Bounty Triple 85g, Maltesers Big Bag 58.5g, Galaxy Milk Little Bit More 75g, Snickers Creamy Peanut Butter Trio 54.9g McCoy's, Hula Hoops, Discos, Wheat McCoy’s All Varieties 45-47.5g, Hula Hoops Big Hoops All Varieties Crunchies, Skips and Nik Naks 2 for 50g, Discos Salt & Vinegar 56g, Wheat Crunchies Crispy Bacon 50g, £1.50 Skips Prawn Cocktail 40g, Nik Naks -

Simei 2009 Informative Dossier on the Beer Industry

THE FIRST 10 NATIONAL BEER MARKETS SIMEI 2009 Rank Nation Population Beer production % Per head INFORMATIVE DOSSIER (Million (million hl) Variations 2008 inhabitants) 2000 2008 ON THE BEER INDUSTRY 1 CHINA 1.339 220 410 +76,5 32 litres/year 2 USA 302 233 232 -0.3 83 litres/year 2008 World Production and Consumption 3 URSS 141 55 114 +107,7 81 litres/year 4 BRAZIL 191 83 106 +29 57 litres/year Again in 2008, despite the general financial and economic crisis the world beer markets managed to record an upward trend. 5 GERMANY 82 110 103 -8,3 111 litres/year According to the data published in the latest Barth Report, world consumption and production of beer in 2008 totalled 1.816 6 MEXICO 105 58 82 +42 60 litres/year million hectolitres, showing a 1.6% increase on the previous year, lower though than average growth rates (approx. 3% per 7 JAPAN 128 71 61 -13,9 52 litres/year annum) of the recent past. Consumption did however slow down on some important markets, particularly in the last three 8 UNITED KINGDOM 60 55 50 -10,5 88 litres/year months of the year. World consumption per head settled at 27 litres/per year. 9 POLOND 38 24 36 +48,3 93 litres/year 10 SPAIN 45 26 33 +26,5 84 litres/year The world consumption of beer recorded a better trend than other alcoholic drinks, in view of certain decisive advantages: Top 10 2.431 935 1.227 +31,2 50 litres/year - beer is the least alcoholic drink and as such creates less “alarmism” with consumers and authorities Other markets 4.299 445 589 +32,4 14 litres/year - beer is the alcoholic drink that -

Drinks Industry Sustainability Index - Trends Report 2020

Drinks Industry Sustainability Index - Trends Report 2020 1 The Drinks Industry Sustainability Index – Trends Report 2020 Contents Foreword 4 Work with NGOs which challenge the company to do better 20 Welcome 6 Innovate and use eco-design tools 21 Retailers will keep challenging suppliers Executive summary 7 on packaging 23 Push to increase the availability of rPET 24 Strategy and culture 9 Consider switching from glass to cans 24 Leading insights – 2020 Action points 9 Work with retailers on zero plastic store trials 25 Collaboration is key: across industry and supply chains 10 Waste 26 Set challenging targets which include Leading insights - 2020 Action points: 27 the supply chain 11 Waste can be energy 27 Employees want action and agency 12 Waste as animal feed can help feed people 27 Empower employees to support Waste can create brand stories 28 sustainability goals 13 Waste partners can help find effective solutions 28 Investors are driving a more Adopt a circular approach for by-products sustainable industry 14 and waste materials 30 Think sustainability across brand Audit stock and invest in inventory management 31 and be driven by peers 14 There is increased pressure to re-distribute 31 Work to support the farmers in your supply chain 15 Water 32 Leading insights - 2020 Action points: 33 Packaging 16 Water is a strategic priority 33 Leading insights - 2020 Action points: 17 Set clear, challenging targets and use Openly address consumer concerns about established reporting 34 plastic and packaging 17 Certification is setting new -

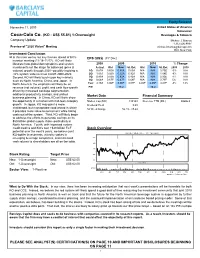

Please See Analyst(S) Certification(S) on Page 10 and Important Disclosures Beginning on Page 11 1

Equity Research November 11, 2009 United States of America Consumer Coca-Cola Co. (KO - US$ 55.81) 1-Overweight Beverages & Tobacco Company Update Michael J. Branca 1.212.526.4887 Preview of "2020 Vision" Meeting [email protected] BCI, New York Investment Conclusion In this note we lay out key themes ahead of KO's EPS (US$) (FY Dec) investor meeting (11/16-11/17). KO will likely illustrate how global demographics and system 2008 2009 2010 % Change investments set the stage for balanced (price & Actual Old New St. Est. Old New St. Est. 2009 2010 volume) growth through 2020--possibly implying a 1Q 0.67A 0.65A 0.65A 0.65A N/A N/A 0.75E -3% N/A ~6% system wide revenue CAGR 2008-2020. 2Q 1.01A 0.92A 0.92A 0.92A N/A N/A 1.04E -9% N/A Second, KO will likely touch upon key markets 3Q 0.83A 0.82A 0.82A 0.82A N/A N/A 0.90E -1% N/A such as North America, China, and Japan. In 4Q 0.64A 0.67E 0.67E 0.68E N/A N/A 0.73E 5% N/A North America, the emphasis will likely be on Year 3.15A 3.06E 3.06E 3.07E 3.45E 3.45E 3.42E -3% 13% revenue (not volume), profit, and cash flow growth P/E 18.2 16.2 driven by increased package segmentation, additional productivity savings, and unified Market Data Financial Summary business planning. In China, KO will likely show the opportunity in a market with mid-teen category Market Cap (Mil.) 130149 Revenue TTM (Mil.) 30606.0 growth. -

The Oc&C Grocer Index 2015

THE OC&C GROCER INDEX 2015 FORAGING FOR NOC&C’s aEnnual reWview of the U K’Gs top 150 Rfood and Osoft drinkW producers TH Reproduced with permission from oc&c top 150 index 2015 28 | The Grocer | 19 September 2015 Get the full story at thegrocer.co.uk Get the full story at thegrocer.co.uk 19 September 2015 | The Grocer | 29 IN ASSOCIATION WITH Which way is growth? Alec Mattinson Sales and profit growth has slumped, the latest OC&C Index for The Grocer reveals, but own label is finding its way more successfully through a changed landscape than the brands onventional wisdom says own-label goods are the unglamorous, low-rent cousins of the all-singing, all-dancing Cand all-conquering consumer brands. Yet the recent disruption to UK grocery has affected suppliers and retailers in myriad ways, and one of the most significant is that the rules around unbranded players have been rewritten. We are now living in the era of own label. Own-brand suppliers are growing over three times faster than branded suppliers, largely because the sector has been better able to navigate around the roadblock of the price war and collapsing traditional supermarket sales. That collapse is partly responsible for The OC&C Grocer Index 2015 painting a downbeat picture, where the woes of the supermarkets are splashed all over the canvas. The annual rate of revenue growth across the Top 150 dipped to 2.9% – well below the long-term aver- age growth rate of 4.2% and a big drop from last year’s 5.8% growth. -

Innocent Good All Round Report 2019

2019 edition innocent drinks the good times innocent is bottling up some goodness drinks people and culture growth company sustainability giving back spills all B Corp nutrition We’re on a mission to become good all round and this newspaper shares our progress in 2019. Cont pg 2 good stuff stuff we’re stuff for you Much like our drinks, we’re making better Good stuff you can stuffing this newspaper full There are always things we can do to get involved. of good stuff. do better. So we've put that in too. 2 introduction B Corp finance sustainability nutrition giving back people and culture people and the planet, and setting a a little note from our chief squeezer more balanced measure of business success. contents has brought rapid change to both businesses and individuals. Our purpose, As part of the B Corp movement, we vision and values now seem more relevant commit to transparent and measurable 3 B Corp than ever and it has increased our social and environmental performance. determination to grow our business in a This brings rigour to our business, responsible and sustainable way. This supports our purpose, and shows that 6 finance report details what we are doing to continue being good all round is not only the to make balanced progress across all right thing to do, but the smart thing to aspects of our business, and how we’re do. Which our continued growth around 9 sustainability getting on. the world hopefully shows. As a B Corp we can shout much louder together 9 recycling activists We’re not perfect by any means. -

Weekly Update Monday, June 18, 2018

Weekly Update Monday, June 18, 2018 Stocks End Down As Investors Look Past U.S.-China Trade Disputes. U.S. stocks closed lower on Friday as investors looked past signs of escalating Mary Burke Partner Washington-Beijing trade tensions, an issue that is seen as a major potential headwind. President Donald Trump approved tariffs on about $50 billion of 312.348.7081 Chinese goods, marking the latest escalation in the trade dispute. [email protected] The Dow Jones Industrial Average decreased 0.9% on the week, William Whipple finishing at 25,090. Partner 312.348.7076 The S&P 500 remained unchanged on the week, finishing at 2,779. [email protected] The NASDAQ Composite gained 1.3% on the week, finishing at 7,746. Lakeshore Food Advisors, LLC Yield on the 10-year Treasury declined one basis during the week, 20 North Wacker Drive ending at 2.92%. Suite 1701 Chicago, IL 60606 Crude oil decreased 2.3% on the week, ending at $64.24 per barrel. Corn decreased 4.5% on the week, ending at $3.61 per bushel. NASDAQ Highs: BJ's Restaurants Inc., Cal-Maine Foods, Inc., Central Garden & Pet Company, The Cheesecake Factory, Coffee Holding Company Inc., Dunkin’ Donuts, John B. Sanfilippo & Son Inc., Noodles & Company Lows: Papa John's Pizza, Rocky Mountain Chocolate Factory NYSE Highs: Boston Beer Company, Brinker International, CF Industries, Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc., Diageo plc, Domino's Pizza, The Mosaic Company, Pinnacle Foods Inc., Shake Shack, Sysco Corporation, Zoetis Inc., Lows: Coca-Cola FEMSA Featured Stocks of the Week: Treehouse Foods Inc. -

SDI DEC09 Web.Pdf

Portola Europe has developed its new Easy Flip sports closure using their reputable light weighting technologies. The new flip top design has a visual tamper evidence that remains on the dust cover (no throw away bands), it is easy to open and closes with an audible snap for re-seal. Easy Flip has an integral double hinge allowing the consumer to hold the dust cover at 180 degrees for ease of consumption. Easy Flip has a long spout for drinking comfort, and features the same high flow rate as our other 3 piece sports closures Available with natural or opaque covers in a wide range of colours. Ergonomically designed, the Easy Flip double hinge fits inside the overall diameter of the closure; thus ensuring that it will perform on existing capping heads with minimal adjustment within the filling machine. As leaders of light weight closures technology, Portola Europe have reduced the weight of Easy Flip by 28% of polymer compared to a normal 3 piece sports closure, so making it one of the lightest functional 2 piece sports closures. Available for 28mm PCO1810 followed by 38mm & 30mm finishes being developed in tandem. Portola Europe is a ISO 14001 Certified Operation Portola Packaging are a leading global supplier of plastic CAPS and CLOSURES for the Food and Beverage Industries. The Easy Flip is a Portola Registered Design www.portola.eu.com Portola Packaging Ltd. PORTOLA s.r.o “Portola” LLC 3 Carriage Drive Prmyslová 2724 Akademika Koroleva ul, 8/1, White Rose Way CZ 440 01 Louny Moscow, Doncaster, Czech Republic.