Sixty Morning Talks by Andy Fitch, Which Was Published in 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texts G7 Sout Pole Expeditions

READING CLOSELY GRADE 7 UNIT TEXTS AUTHOR DATE PUBLISHER L NOTES Text #1: Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen (Photo Collages) Scott Polar Research Inst., University of Cambridge - Two collages combine pictures of the British and the Norwegian Various NA NA National Library of Norway expeditions, to support examining and comparing visual details. - Norwegian Polar Institute Text #2: The Last Expedition, Ch. V (Explorers Journal) Robert Falcon Journal entry from 2/2/1911 presents Scott’s almost poetic 1913 Smith Elder 1160L Scott “impressions” early in his trip to the South Pole. Text #3: Roald Amundsen South Pole (Video) Viking River Combines images, maps, text and narration, to present a historical NA Viking River Cruises NA Cruises narrative about Amundsen and the Great Race to the South Pole. Text #4: Scott’s Hut & the Explorer’s Heritage of Antarctica (Website) UNESCO World Google Cultural Website allows students to do a virtual tour of Scott’s Antarctic hut NA NA Wonders Project Institute and its surrounding landscape, and links to other resources. Text #5: To Build a Fire (Short Story) The Century Excerpt from the famous short story describes a man’s desperate Jack London 1908 920L Magazine attempts to build a saving =re after plunging into frigid water. Text #6: The North Pole, Ch. XXI (Historical Narrative) Narrative from the =rst man to reach the North Pole describes the Robert Peary 1910 Frederick A. Stokes 1380L dangers and challenges of Arctic exploration. Text #7: The South Pole, Ch. XII (Historical Narrative) Roald Narrative recounts the days leading up to Amundsen’s triumphant 1912 John Murray 1070L Amundsen arrival at the Pole on 12/14/1911 – and winning the Great Race. -

The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-17-2013 The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience Erica Rostedt [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rostedt, Erica, "The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience" (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1665. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1665 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Erica Allison Rostedt B.A. University of Washington, 2004 May, 2013 © 2013, Erica Allison Rostedt ii Table -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Stony Brook Press V. 19, N. 06.PDF (8.570Mb)

B 3. Vol. XIX No. 6 Don't Let The Door Hit Ya On The Tex-Ass November 12,1997 ISSUES Beyond Bubba University EMS and Fire Volunteers Practice Heavy Rescues By Michael Yeh mary responder for fires, vehicular extrication, bondage that comes with spinal immobilization. "I and hazardous materials," said SBVAC President never, ever want to be in a KED in my life," said The Stony Brook Volunteer Ambulance Corps Tim True. Christina Freudenberg, EMT-D of the tight jacket- paid its last respects to an old veteran -- by hack- "We need a new door there anyway," said like protective device. "But everybody was pretty ing it to pieces. Deputy Chief of Operations Jason Hellmann while cool, and they did a very good job." Emergency medical technicians and firefighters surveying the metallic carnage. "Until now, some "I felt that the technicians had control of what who serve the campus community participated in people thought heavy rescue meant a really fat was going on and were taking care of details that a heavy rescue drill at the Setauket Fire EMT named Bubba!" the accident victim would not normally be aware Department's Station 3 on SBVAC participants entered the of," said Kevin Kenny, EMT-Critical Care. Thursday, October 23. This was ambulance to find two other But most importantly, this drill gave the SBVAC the first mutual training event semi-conscious patients in the and Setauket volunteers a chance to see each other between SBVAC and neighbor- back. Since high-speed car acci- in action and to learn how to work together at a ing fire departments. -

5.00 #214 February/MARCH 2008 the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics Summer Writing Program 2008

$5.00 #214 FEBRUARY/MARCH 2008 The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics Summer Writing Program 2008 7EEKLY7ORKSHOPSs*UNEn*ULYs"OULDER #/ WEEK ONE: June 16–22 The Wall: Troubling of Race, Class, Economics, Gender and Imagination Samuel R. Delany, Marcella Durand, Laird Hunt, Brenda Iijima, Bhanu Kapil, Miranda Mellis, Akilah Oliver, Maureen Owen, Margaret Randall, Max Regan, Joe Richey, Roberto Tejada and Julia Seko (printshop) WEEK TWO: June 23–29 Elective Affinities: Against the Grain: Writerly Utopias Will Alexander, Sinan Antoon, Jack Collom, Linh Dinh, Anselm Hollo, Daniel Kane, Douglas Martin, Harryette Mullen, Laura Mullen, Alice Notley, Elizabeth Robinson, Eleni Sikelianos, Orlando White and Charles Alexander (printshop) WEEK THREE: June 30–July 6 Activism, Environmentalism: The Big Picture Amiri Baraka, Lee Ann Brown, Junior Burke, George Evans, Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Lewis MacAdams, Eileen Myles, Kristin Prevallet, Selah Saterstrom, Stacy Szymaszek, Anne Waldman, Daisy Zamora and Karen Randall (printshop) WEEK FOUR: July 7–13 Performance, Community: Policies of the USA in the Larger World Dodie Bellamy, Rikki Ducornet, Brian Evenson, Raymond Federman, Forrest Gander, Bob Holman,Pierre Joris, Ilya Kaminsky, Kevin Killian, Anna Moschovakis, Sawako Nakayasu, Anne Tardos, Steven Taylor, Peter & Donna Thomas (printshop) Credit and noncredit programs available Poetry s&ICTIONs4RANSLATION Letterpress Printing For more information on workshops, visit www.naropa.edu/swp. To request a catalog, call 303-245-4600 or email [email protected]. Keeping the world safe for poetry since 1974 THE POETRY PROJECT ST. MARK’S CHURCH in-the-BowerY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.com #214 FEBRUARY/MARCH 2008 NEWSLETTER EDITOR John Coletti 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 6 READING REPORTS THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. -

Sandler Uccs 0892D 10567.Pdf (1.548Mb)

EXPLORING THE EVOLUTION OF FIRST-YEAR EDUCATORS’ DISPOSITIONS TOWARD DIVERSE STUDENTS AND PERCEPTIONS OF PERFORMANCE AS CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE EDUCATORS: A PORTRAITURE CASE STUDY by HOLLY A. SANDLER B.A., University of Florida, 1983 M.S., Pace University, 1995 M.A., New York Institute of Technology, 2001 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Colorado Colorado Springs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Leadership, Research, and Foundations 2020 © 2020 HOLLY A. SANDLER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This dissertation for the Doctor of Philosophy degree by Holly A. Sandler has been approved for the Department of Leadership, Research, and Foundations by Robert Mitchell, Chair Sylvia Mendez Andrea Bingham Patricia Witkowsky Leslie Grant Date July 13, 2020 ii Sandler, Holly A. (Ph.D., Educational Leadership, Research, and Policy) Exploring the Evolution of First-year Educators’ Dispositions Towards Diverse Students and Perceptions of Performance as Culturally Responsive Educators: A Portraiture Case Study Dissertation directed by Assistant Professor Robert Mitchell ABSTRACT As we enter the year 2020 the plurality of races and ethnicities within the United States is reflected in the students attending our nation’s public schools. For the first time in American history the majority of students attending the nation’s public schools are students of color. The multiplicity of races and ethnicities of the nation’s students, however, is not mirrored in the demographics of public-school teachers who remain 77% White and 80% female. Researchers have found the absence of parity in student-teacher demographic problematic since a large number of White adults, teachers among them, are reported to accept negative racial stereotypes as truth. -

235-Newsletter.Pdf

The Poetry Project Newsletter Editor: Paul Foster Johnson Design: Lewis Rawlings Distribution: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff Artistic Director: Stacy Szymaszek Program Coordinator: Arlo Quint Program Assistant: Nicole Wallace Monday Night Coordinator: Simone White Monday Night Talk Series Coordinator: Corrine Fitzpatrick Wednesday Night Coordinator: Stacy Szymaszek Friday Night Coordinator: Matt Longabucco Sound Technician: David Vogen Videographer: Andrea Cruz Bookkeeper: Lezlie Hall Archivist: Will Edmiston Box Office: Aria Boutet, Courtney Frederick, Gabriella Mattis Interns/Volunteers: Mel Elberg, Phoebe Lifton, Jasmine An, Davy Knittle, Olivia Grayson, Catherine Vail, Kate Nichols, Jim Behrle, Douglas Rothschild Volunteer Development Committee Members: Stephanie Gray, Susan Landers Board of Directors: Gillian McCain (President), John S. Hall (Vice-President), Jonathan Morrill (Treasurer), Jo Ann Wasserman (Secretary), Carol Overby, Camille Rankine, Kimberly Lyons, Todd Colby, Ted Greenwald, Erica Hunt, Elinor Nauen, Evelyn Reilly and Edwin Torres Friends Committee: Brooke Alexander, Dianne Benson, Will Creeley, Raymond Foye, Michael Friedman, Steve Hamilton, Bob Holman, Viki Hudspith, Siri Hustvedt, Yvonne Jacquette, Patricia Spears Jones, Eileen Myles, Greg Masters, Ron Padgett, Paul Slovak, Michel de Konkoly Thege, Anne Waldman, Hal Willner, John Yau Funders: The Poetry Project’s programs and publications are made possible, in part, with public funds from The National Endowment for the Arts. The Poetry Project’s programming is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Poetry Project’s programs are supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council. -

The Body-Snatchers

The Body-Snatchers (1884) Robert Louis Stevenson EVERY night in the year, four of us sat in the small parlour of the George at Debenham—the undertaker, and the landlord, and Fettes, and myself. Sometimes there would be more; but blow high, blow low, come rain or snow or frost, we four would be each planted in his own particular arm-chair. Fettes was an old drunken Scotchman, a man of education obviously, and a man of some property, since he lived in idleness. He had come to Debenham years ago, while still young, and by a mere continuance of living had grown to be an adopted townsman. His blue camlet cloak was a local antiquity, like the church- spire. His place in the parlour at the George, his absence from church, his old, crapulous, disreputable vices, were all things of course in Debenham. He had some vague Radical opinions and some fleeting infidelities, which he would now and again set forth and emphasise with tottering slaps upon the table. He drank rum—five glasses regularly every evening; and for the greater portion of his nightly visit to the George sat, with his glass in his right hand, in a state of melancholy alcoholic saturation. We called him the Doctor, for he was supposed to have some special knowledge of medicine, and had been known, upon a pinch, to set a fracture or reduce a dislocation; but beyond these slight particulars, we had no knowledge of his character and antecedents. One dark winter night—it had struck nine some time before the landlord joined us—there was a sick man in the George, a great neighbouring proprietor suddenly struck down with apoplexy on his way to Parliament; and the great man’s still greater London doctor had been telegraphed to his bedside. -

Cinema 2: the Time-Image

m The Time-Image Gilles Deleuze Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Caleta M IN University of Minnesota Press HE so Minneapolis fA t \1.1 \ \ I U III , L 1\) 1/ ES I /%~ ~ ' . 1 9 -08- 2000 ) kOTUPHA\'-\t. r'Y'f . ~ Copyrigh t © ~1989 The A't1tl ----resP-- First published as Cinema 2, L1111age-temps Copyright © 1985 by Les Editions de Minuit, Paris. ,5eJ\ Published by the University of Minnesota Press III Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 f'tJ Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 1'::>55 Fifth printing 1997 :])'''::''531 ~ Library of Congress Number 85-28898 ISBN 0-8166-1676-0 (v. 2) \ ~~.6 ISBN 0-8166-1677-9 (pbk.; v. 2) IJ" 2. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or othenvise, ,vithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. Contents Preface to the English Edition Xl Translators'Introduction XV Chapter 1 Beyond the movement-image 1 How is neo-realism defined? - Optical and sound situations, in contrast to sensory-motor situations: Rossellini, De Sica - Opsigns and sonsigns; objectivism subjectivism, real-imaginary - The new wave: Godard and Rivette - Tactisigns (Bresson) 2 Ozu, the inventor of pure optical and sound images Everyday banality - Empty spaces and stilllifes - Time as unchanging form 13 3 The intolerable and clairvoyance - From cliches to the image - Beyond movement: not merely opsigns and sonsigns, but chronosigns, lectosigns, noosigns - The example of Antonioni 18 Chapter 2 ~ecaPitulation of images and szgns 1 Cinema, semiology and language - Objects and images 25 2 Pure semiotics: Peirce and the system of images and signs - The movement-image, signaletic material and non-linguistic features of expression (the internal monologue). -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2kb1h96x Author Smith, Matthew Bingham Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry By Matthew Bingham Smith A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Professor Mairi McLaughlin Professor Ann Smock Professor Lyn Hejinian Summer 2015 Abstract Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry by Matthew Bingham Smith Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Lucey, Chair My dissertation offers a transnational perspective on the lively dialogue between French and American poetry since the 1970s. Focusing on the institutions and practices that mediate this exchange, I show how American and French poets take up, challenge or respond to shifts in the poetic field tied to new cross-cultural networks of circulation. In so doing, I also demonstrate how poets imagine and realize a diverse set of competing publics. This work is divided into three chapters. After analyzing in my introduction the web of poets and institutions that have enabled and sustained this exchange, I show in my first chapter how collaborations between writers and translators have greatly impacted recent poetry in a case study of two American works: Andrew Zawack’s Georgia (2009) and Bill Luoma’s My Trip to New York City (1994). -

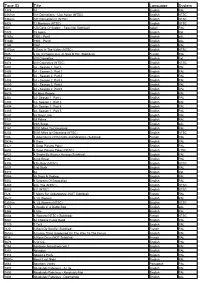

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

Blake, Duncan, and the Politics of Writing from Myth

ARTICLE upbringing, Duncan read Blake as a poet of hermetic vi- sion.3 For Duncan, Blake sees clearly into the essential truth of his own time, and this insight carries a deep social re- sponsibility. In Roots and Branches and Fictive Certainties, Blake, Duncan, and the Politics of Duncan draws from his sense of an occult Blake to deepen Writing from Myth his own exploration of the poetic textures of personal ex- perience. In Bending the Bow, he takes his reading of Blake beyond the personal and poetic implications of occult mys- By Linda Freedman ticism toward an intensely ethical political engagement. This does not represent a rupture from the concerns ex- Linda Freedman ([email protected]) is a lecturer pressed in Roots and Branches and Fictive Certainties, but in British and American literature at University College a development. In both instances, Duncan comes into his London. She is a graduate of Oxford and London and a creative potential thinking about Blake in terms of touch. former fellow of Selwyn College, Cambridge. She is the The act of touching something, or someone, had a partic- author of Emily Dickinson and the Religious Imagina- ular personal significance for him as a signifier of both in- tion (Cambridge University Press, 2011) and is current- timacy and reality. At the age of three he was hurt in an ly writing a book about William Blake and America. accident in the snow and became cross-eyed so that he saw She has a particular interest in transatlantic connec- double. In Roots and Branches he spoke about the effects tions and in the relationship between literature, reli- of his injury in metaphysical terms: “I had the double re- gion, and the visual arts.