Texts G7 Sout Pole Expeditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of Polar Programs

DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF SURFACE TRAVERSE CAPABILITIES IN ANTARCTICA COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION DRAFT (15 January 2004) FINAL (30 August 2004) National Science Foundation 4201 Wilson Boulevard Arlington, Virginia 22230 DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF SURFACE TRAVERSE CAPABILITIES IN ANTARCTICA FINAL COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Purpose.......................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation (CEE) Process .......................................................1-1 1.3 Document Organization .............................................................................................................1-2 2.0 BACKGROUND OF SURFACE TRAVERSES IN ANTARCTICA..................................2-1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................2-1 2.2 Re-supply Traverses...................................................................................................................2-1 2.3 Scientific Traverses and Surface-Based Surveys .......................................................................2-5 3.0 ALTERNATIVES ....................................................................................................................3-1 -

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

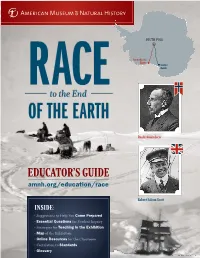

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

The South Polar Race Medal

The South Polar Race Medal Created by Danuta Solowiej The way to the South Pole / Sydpolen. Roald Amundsen’s track is in Red and Captain Scott’s track is in Green. The South Polar Race Medal Roald Amundsen and his team reaching the Sydpolen on 14 Desember 1911. (Obverse) Captain R. F. Scott, RN and his team reaching the South Pole on 17 January 1912. (Reverse) Created by Danuta Solowiej Published by Sim Comfort Associates 29 March 2012 Background The 100th anniversary of man’s first attainment of the South Pole recalls a story of two iron-willed explorers committed to their final race for the ultimate prize, which resulted in both triumph and tragedy. In July 1895, the International Geographical Congress met in Lon- don and opened Antarctica’s portal by deciding that the southern- most continent would become the primary focus of new explora- tion. Indeed, Antarctica is the only such land mass in our world where man has ventured and not found man. Up until that time, no one had explored the hinterland of the frozen continent, and even the vast majority of its coastline was still unknown. The meet- ing touched off a flurry of activity, and soon thereafter national expeditions and private ventures started organizing: the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration had begun, and the attainment of the South Pole became the pinnacle of that age. Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (1872-1928) nurtured at an early age a strong desire to be an explorer in his snowy Norwegian surroundings, and later sailed on an Arctic sealing voyage. -

The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-17-2013 The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience Erica Rostedt [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rostedt, Erica, "The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience" (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1665. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1665 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Erica Allison Rostedt B.A. University of Washington, 2004 May, 2013 © 2013, Erica Allison Rostedt ii Table -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

JOURNAL Number Six

THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY JOURNAL Number Six Antarctic Exploration Sir Ernest Shackleton MARCH 2012 1 Shackleton and a friend (Oliver Locker Lampson) in Cromer, c.1910. Image courtesy of Cromer Museum. 2 The James Caird Society Journal – Number Six March 2012 The Centennial season has arrived. Having celebrated Shackleton’s British Antarctic (Nimrod) Expedition, courtesy of the ‘Matrix Shackleton Centenary Expedition’, in 2008/9, we now turn our attention to the events of 1910/12. This was a period when 3 very extraordinary and ambitious men (Amundsen, Scott and Mawson) headed south, to a mixture of acclaim and tragedy. A little later (in 2014) we will be celebrating Sir Ernest’s ‘crowning glory’ –the Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition 1914/17. Shackleton failed in his main objective (to be the first to cross from one side of Antarctica to the other). He even failed to commence his land journey from the Weddell Sea coast to Ross Island. However, the rescue of his entire team from the ice and extreme cold (made possible by the remarkable voyage of the James Caird and the first crossing of South Georgia’s interior) was a remarkable feat and is the reason why most of us revere our polar hero and choose to be members of this Society. For all the alleged shenanigans between Scott and Shackleton, it would be a travesty if ‘Number Six’ failed to honour Captain Scott’s remarkable achievements - in particular, the important geographical and scientific work carried out on the Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions (1901-3 and 1910-12 respectively). -

The Antarctic Treaty

The Antarctic Treaty Measures adopted at the Thirty-ninth Consultative Meeting held at Santiago, Chile 23 May – 1 June 2016 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty November 2017 Cm 9542 © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at Treaty Section, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, King Charles Street, London, SW1A 2AH ISBN 978-1-5286-0126-9 CCS1117441642 11/17 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majestyʼs Stationery Office MEASURES ADOPTED AT THE THIRTY-NINTH ANTARCTIC TREATY CONSULTATIVE MEETING Santiago, Chile 23 May – 1 June 2016 The Measures1 adopted at the Thirty-ninth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting are reproduced below from the Final Report of the Meeting. In accordance with Article IX, paragraph 4, of the Antarctic Treaty, the Measures adopted at Consultative Meetings become effective upon approval by all Contracting Parties whose representatives were entitled to participate in the meeting at which they were adopted (i.e. all the Consultative Parties). The full text of the Final Report of the Meeting, including the Decisions and Resolutions adopted at that Meeting and colour copies of the maps found in this command paper, is available on the website of the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat at www.ats.aq/documents. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 78/Tuesday, April 23, 2019/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 78 / Tuesday, April 23, 2019 / Rules and Regulations 16791 U.S.C. 3501 et seq., nor does it require Agricultural commodities, Pesticides SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The any special considerations under and pests, Reporting and recordkeeping Antarctic Conservation Act of 1978, as Executive Order 12898, entitled requirements. amended (‘‘ACA’’) (16 U.S.C. 2401, et ‘‘Federal Actions to Address Dated: April 12, 2019. seq.) implements the Protocol on Environmental Justice in Minority Environmental Protection to the Richard P. Keigwin, Jr., Populations and Low-Income Antarctic Treaty (‘‘the Protocol’’). Populations’’ (59 FR 7629, February 16, Director, Office of Pesticide Programs. Annex V contains provisions for the 1994). Therefore, 40 CFR chapter I is protection of specially designated areas Since tolerances and exemptions that amended as follows: specially managed areas and historic are established on the basis of a petition sites and monuments. Section 2405 of under FFDCA section 408(d), such as PART 180—[AMENDED] title 16 of the ACA directs the Director the tolerance exemption in this action, of the National Science Foundation to ■ do not require the issuance of a 1. The authority citation for part 180 issue such regulations as are necessary proposed rule, the requirements of the continues to read as follows: and appropriate to implement Annex V Regulatory Flexibility Act (5 U.S.C. 601 Authority: 21 U.S.C. 321(q), 346a and 371. to the Protocol. et seq.) do not apply. ■ 2. Add § 180.1365 to subpart D to read The Antarctic Treaty Parties, which This action directly regulates growers, as follows: includes the United States, periodically food processors, food handlers, and food adopt measures to establish, consolidate retailers, not States or tribes. -

J.S. Antarctic Projects Officer N

J.S. ANTARCTIC PROJECTS OFFICER N VOLUME III NUMBER 5 JANUARY 1962 Wednesday, January 17 [1912]. -- Camp 69. T. -220 at start. Night -21°. The Pole. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected. Great God! this is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority. Well, it is something to have got here, and the wind may be our friend to--morrow. We have had a fat Polar hoosh in spite of our chagrin, and feel com- fortable inside -- added a small stick of chocolate and the queer taste of a cigarette brought by Wilson. Now for the run home and a desperate struggle. I wonder if we can do it. Thursday morning, January 18. -- Decided after suing up all observations that we were 3.5 miles away from the Pole -- one mile beyond it and 3 to the right. More or less in this direction Bowers saw a cairn or tent. We have just arrived at this tent, 2 miles from our camp, therefore about li miles from the Pole. In the tent we find a record of five Norwegians having been here, as follows: Roald Amundsen Olav Olavson Bjaaland Humor Hanssen Svorre H. Hassel Oscar Wisting. 16 Dec. 1911. Captain Robert F. Scott, Scotts Lest Expedition, arranged by Leonard Huxley, vol. I, pp. 374-375. Volume III, No. 5 January 1962 CONTENTS The Month in Review 1 International Flights in the Antarctic 2 South Pole -- Fifty Years After 4 Dirty Diamond Mine 4 Topo North Completed 5 Marine Life Under Ross Ice Shelf 6 Lakes with Warm Water 7 The Fiftieth in Washington 8 Suggestions for Reading 9 New Zealand Memorial to Admiral Byrd 11 Antarctic Chronology, 1961-62 12 Material for this issue of the Bulletin was adapted from press releases issued by the Department of Defense and the National Science Foundation and from incoming dispatches. -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

Discovery: Crew List

OFFICIAL DISCOVERY EXPEDITION CREW The Discovery Crew included a mix of Royal Navy, Merchant Navy and civilian personnel. CREW Captain Scott, Expedition Leader Albert Armitage, Navigator and Second-in-Command Charles Royds, First Lieutenant Michael Barne, Second Lieutenant Ernest Shackleton, Third Lieutenant George Mulock, Third Lieutenant Reginald Skelton, Chief Engineer and Official Photographer James Dellbridge, Second Engineer William Lashly, Chief Stoker Arthur Quarterly, Leading Stoker Frank Plumley, Stoker Thomas Whitfield, Stoker Page, Stoker Arthur Pilbeam, Leading Seaman Frank Wild, Seaman Thomas Crean, Seaman John Baker, Seaman Bonner, Seaman George Crouchers, Seaman James Dell, Seaman George Vince, Seaman Walker, Seaman Waterman, Seaman William Weller, Seaman William Heald, Seaman Mardon, Seaman Masterton, Seaman Peters, Seaman Evans, Seaman Sinclair, Seaman Thomas Williamson, Seaman William Smythe, Petty Officer Edgar Evans, Petty Officer Ernest Joyce, Petty Officer David Allan, Petty Officer Jacob Cross, Petty Officer Thomas Kennar, Petty Officer William Macfarlane, Petty Officer Reginald Ford, Chief Steward Arthur Blissett, Steward Clarence Hare, Steward OFFICIAL Dowsett, Steward Gilbert Scott, Steward Roper, Cook Brett, Cook Charles Clarke, 2nd Cook Clarke, Laboratory Assistant Buckridge, Laboratory Assistant Fred Dailey, Carpenter James Duncan, Carpenter’s Mate & Shipwright Thomas Feather, Boatswain (Bosun) Miller, Sailmaker Hubert, Donkeyman SCIENTIFIC Dr George Murray, Chief Scientist (left the ship at Cape Town) Louis Bernacchi, Physicist Hartley Ferrar, Geologist Thomas Vere Hodgson, Marine Biologist Reginald Koettlitz, Doctor Edward Wilson, Junior Doctor and Zoologist .