The Deadly Affairs of John Figaro Newton Or a Senseless Appeal to Reason and an Elegy for the Dreaming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dark Webs Goth Subcultures in Cyberspace

Dark Webs Goth Subcultures in Cyberspace Jason Whittaker University College Falmouth The rapport between Goth subcultures and new technologies has often been a subject of fascination for those who are both part of that subculture and external observers. William Gibson, who provided much of the impetus for such intersec- tions via his contributions to cyberpunk, made the connection between technol- ogy and Gothic rather embarrassingly explicit in his 1986 novel, Count Zero. Less mortifying was the crossover that occurred in the late eighties and nineties between Goth and Industrial music, particularly via bands such as Nine Inch Nails or Frontline Assembly, exploiting a hardcore techno sound combined with a strongly Goth-influenced aesthetic.1 This connection between the Gothic and technoculture has contributed to the survival of a social grouping that Nick Mercer, in 21st Century Goth (2002), refers to as the most vibrant community online, and is also the subject of several studies by Paul Hodkinson in particular. This paper is not especially concerned with the Gothic per se, whether it can tell us something about the intrinsic nature of the web or vice versa, but more with the practice of a youth subculture that does indeed appear to be flourishing in cyberspace, particularly the phe- nomenon of net.Goths that has emerged in recent years. Claims that sites and newsgroups form virtual communities are, of course, not specific to Goths. With the emergence of the Internet into popular consciousness in the early to mid- nineteen-nineties following the invention of the World Wide Web, commenta- tors such as Howard Rheingold in The Virtual Community (1995) made grand claims for the potential of online or virtual communities. -

Toni Braxton Announces North American Fall Tour

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TONI BRAXTON ANNOUNCES NORTH AMERICAN FALL TOUR Detroit (August 8, 2016) – Seven-time GRAMMY Award-winning singer, songwriter and actress Toni Braxton announces her North American tour. Kicking off on Saturday, October 8 in Oakland, Braxton will tour more than 20 cities, ending with a show in Atlantic City, NJ on Saturday, November 12. Most recently, Braxton released “Love, Marriage & Divorce,” a duets album with Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds. The album took off behind “Hurt You,” the Urban AC #1 duet hit co-written by Toni Braxton & Babyface (with Daryl Simmons and Antonio Dixon), and produced by Babyface. The two also shared the win for Best R&B Album at the 2015 GRAMMY Awards. Today, with over 67 million in sales worldwide and seven GRAMMY Awards, Braxton is recognized as one of the most outstanding voices of this generation. Her distinctive sultry vocal blend of R&B, pop, jazz and gospel became an instantaneous international sensation when she came forth with her first solo recording in 1992. Braxton stormed the charts in the 90’s with the releases of “Toni Braxton” and “Secrets,” which spawned the hit singles and instant classics; “Another Sad Love Song,” “Breathe Again,” “You’re Makin’ Me High,” and “Unbreak My Heart.” Today, Braxton balances the demands of her career with the high priorities of family, health and public service as she raises her two sons Denim and Diezel. This year Toni was the Executive Producer of the highly-rated Lifetime movie “Unbreak My Heart” which was based on her memoir and she is the star of the WEtv hit reality series Braxton Family Values in its fifth season. -

A Collection of Short and Nonfiction

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Spring 5-1-2018 Unlonely: A Collection of Short and Nonfiction Mary Karnes University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Karnes, Mary, "Unlonely: A Collection of Short and Nonfiction" (2018). Master's Theses. 359. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/359 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unlonely: a Collection of Short and Nonfiction by Mary Ryan Karnes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by: Angela Ball, Committee Chair Anne Sanow Charles Sumner Justin Taylor ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Angela Ball Dr. Luis Iglesias Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School May 2018 COPYRIGHT BY Mary Ryan Karnes 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT The following short stories and nonfiction essays were produced by the author during her writing career at the University of Southern Mississippi. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The following work took shape under the counsel of Steve Barthelme, Anne Sanow, and Justin Taylor, all incredible writers and mentors. Steve pushed me toward adulthood in my writing; Anne encouraged me to take risks and to consider form at every turn; Justin saw my work’s strengths where I could only see it faltering. -

With LOWELL's Real Cre a 'Blueberrybb Naatural And•N T Flavored ISSUES I I I I , I I · , I I· W*E N Ee*

I I with LOWELL'S real cre a 'BlueberryBB NaAtural and•n t Flavored ISSUES I I I I , I I · , I I· _ W*e n ee* By Norman Solomon * This daily satellite-TV feed has a captive audi- * While they're about 25 percent of the U.S. pop- To celebrate the arrival of summer, here's an all- ence of more than 8 million kids in classrooms. ulation, a 1997 survey by the American Society of new episode of "Media Jeopardy!" While it's touted as "a tool to educate and engage Newspaper Editors found that they comprise You probably remember the rules: First, listen young adults in world happenings," the broad- only 11.35 percent of the journalists in the news- carefully to the answer. Then, try to come up with cast service sells commercials that go for nearly rooms of this country's daily papers. the correct question. $200,000 per half-minute -- pitched to advertisers What are racial minorities? as a way of gaining access to "the hardest to reach The first category is "Broadcast News." teen viewers." We're moving into Media Double Jeopardy with What is Channel One? our next category, "Fear and Favor." * On ABC, CBS and NBC, the amount of TV net- work time devoted to this coverage has fallen to * During the 1995-96 election cycle, these corpo- * While this California newspaper was co-spon- half of what it was during the late 1980s. rate parents of major networks gave a total of $3.2 soring a local amateur sporting event with Nike What is internationalnews? million in "soft money" to the national last spring, top editors at the paper killed a staff Democratic and Republican parties. -

Cover Story 18 / 19 Side a Fever Ray

Cover Story 18 / 19 Side A Fever Ray Plunge è la rivoluzione sessuale di Karin Dreijer. Difuso lo scorso ottobre, l’album arriva questo mese in formato fisico, assieme a un atteso tour in cui la misteriosa artista svedese del duo The Knife promette di confondere, ancora una volta, le aspettative del pubblico Testo di Giuseppe Zevolli Fotografie di Martin Falck “Nessuno sguardo irrispettoso / Ubriaca e felice, felice in uno spazio sicuro”, mormora la voce robotica di Karjn Dreijer in A Part Of Us, uno dei brani chiave di Plunge, il suo secondo disco a nome Fever Ray. “Una mano nella tua e l’altra stretta in un pugno”, Quest’urgenza di esprimersi è riflessa nell’uso continua. A Part Of Us celebra la sensazione di della voce, per la prima volta in primissimo piano, protezione degli spazi queer, dipinti come delle anni luce dalle cupe distorsioni dell’album del oasi sospese nel tempo, in cui l’espressione della 2009. Fever Ray era un esercizio di camouflage propria identità e del proprio desiderio rifuggono notturno a confronto con la scattante, penetrante dallo sguardo giudicante incontrato troppo spesso elettronica di Plunge. Nonostante la fama di autrice al loro esterno. Uno sguardo proveniente da chi sfuggente e la storia di amore-odio con la stampa, vorrebbe infondere nei loro abitanti un antico senso chiarezza e entusiasmo finiscono per animare di vergogna. Pur essendo reali, tangibili, Dreijer anche la nostra chiacchierata Skype. Dreijer parte rappresenta questi spazi come dei microcosmi in sordina, scandendo qualche breve risposta e felici in anticipazione di un’utopia allargata ancora prendendosi delle brevi pause per riflettere sul in divenire. -

Ican/Ican Associates Presents the 2013 Child Abuse Prevention Poster Art Contest

ICAN/ICAN ASSOCIATES PRESENTS THE 2013 CHILD ABUSE PREVENTION POSTER ART CONTEST THEME: LET’S TAKE CARE OF OUR CHILDREN Contest is open to all 4th, 5th, and 6th Grade Students POSTERS MUST BE POSTMARKED BY: FRIDAY, MARCH 1, 2013 25 AWARDS FOR STUDENTS AND TEACHERS The Winners and Finalists will be honored in April 2013 Visit the ICAN Associates Website at: www.ican4kids.org APRIL IS NATIONAL CHILD ABUSE PREVENTION MONTH The ICAN/ICAN Associates Child Abuse Prevention Month Poster Contest focuses on the health and well-being of children and provides a comfortable forum for discussion in the classroom. This contest emphasizes the importance of child abuse prevention and gives children the ability to convey it to others through their art. Physical and emotional abuse can be reduced with education and awareness and the ICAN/ ICAN Associates Poster Contest is a public awareness campaign that addresses this critical need for protecting and educating our children. WINNERS, FINALISTS, AND THEIR TEACHERS will be invited to participate in the Announcement of Child Abuse Prevention Month when the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors meet in April, 2013. The posters of the winners and finalists have been previously exhibited at: ICAN Policy Committee Meeting Reception ICAN Annual Grief and Loss Conference State Department of Social Services Family Violence Division of the District Attorney’s Office, Criminal Courts Building HOWS Markets, Pasadena and North Hollywood Frances Howard Goldwyn Hollywood Library Los Angeles County Office of Education/Selected District Offices Los Angeles County Ed Edelman Children's Court ICAN/ICAN Associates “Nexus” Training Conference RULES pertaining to this event are enclosed. -

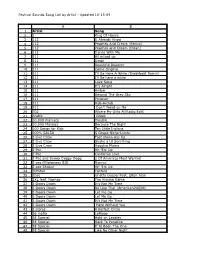

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Texts G7 Sout Pole Expeditions

READING CLOSELY GRADE 7 UNIT TEXTS AUTHOR DATE PUBLISHER L NOTES Text #1: Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen (Photo Collages) Scott Polar Research Inst., University of Cambridge - Two collages combine pictures of the British and the Norwegian Various NA NA National Library of Norway expeditions, to support examining and comparing visual details. - Norwegian Polar Institute Text #2: The Last Expedition, Ch. V (Explorers Journal) Robert Falcon Journal entry from 2/2/1911 presents Scott’s almost poetic 1913 Smith Elder 1160L Scott “impressions” early in his trip to the South Pole. Text #3: Roald Amundsen South Pole (Video) Viking River Combines images, maps, text and narration, to present a historical NA Viking River Cruises NA Cruises narrative about Amundsen and the Great Race to the South Pole. Text #4: Scott’s Hut & the Explorer’s Heritage of Antarctica (Website) UNESCO World Google Cultural Website allows students to do a virtual tour of Scott’s Antarctic hut NA NA Wonders Project Institute and its surrounding landscape, and links to other resources. Text #5: To Build a Fire (Short Story) The Century Excerpt from the famous short story describes a man’s desperate Jack London 1908 920L Magazine attempts to build a saving =re after plunging into frigid water. Text #6: The North Pole, Ch. XXI (Historical Narrative) Narrative from the =rst man to reach the North Pole describes the Robert Peary 1910 Frederick A. Stokes 1380L dangers and challenges of Arctic exploration. Text #7: The South Pole, Ch. XII (Historical Narrative) Roald Narrative recounts the days leading up to Amundsen’s triumphant 1912 John Murray 1070L Amundsen arrival at the Pole on 12/14/1911 – and winning the Great Race. -

The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-17-2013 The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience Erica Rostedt [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rostedt, Erica, "The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience" (2013). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1665. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1665 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Tween Ghost Story: Articulating the Tween Experience A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Erica Allison Rostedt B.A. University of Washington, 2004 May, 2013 © 2013, Erica Allison Rostedt ii Table -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

Preston Sawyer Film and Theater Collection MS.404

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8w66sh5 No online items Preston Sawyer Film and Theater Collection MS.404 Debra Roussopoulos University of California, Santa Cruz 2019 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Preston Sawyer Film and Theater MS.404 1 Collection MS.404 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Preston Sawyer Film and Theater Collection creator: Sawyer, Preston, 1899-1968 Identifier/Call Number: MS.404 Physical Description: 8 Linear Feet27 boxes Date (inclusive): 1907-1959 Abstract: This collection contains photographs, lobby cards, correspondence, ephemera, and realia. Storage Unit: 1-27 Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. For more information on copyright or to order a reproduction, please visit guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll/reproduction-publication. Preferred Citation Preston Sawyer Film and Theater Collection. MS 404. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Biographical / Historical The Sawyer family of Santa Cruz, California, were avid movie and theater aficionados. The materials in this collection were gathered mainly by Preston Sawyer, and contributed to by Ariel and Gertrude Sawyer. Ariel Sawyer spent time working in Hollywood from 1922-1925. -

The Arrow of Time Volume 7 Paul Davies Summer 2014 Beyond Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science, Arizona State University, Journal Homepage P.O

The arrow of time Volume 7 Paul Davies Summer 2014 Beyond Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science, Arizona State University, journal homepage P.O. Box 871504, Tempe, AZ 852871504, USA. www.euresisjournal.org [email protected] Abstract The arrow of time is often conflated with the popular but hopelessly muddled concept of the “flow” or \passage" of time. I argue that the latter is at best an illusion with its roots in neuroscience, at worst a meaningless concept. However, what is beyond dispute is that physical states of the universe evolve in time with an objective and readily-observable directionality. The ultimate origin of this asymmetry in time, which is most famously captured by the second law of thermodynamics and the irreversible rise of entropy, rests with cosmology and the state of the universe at its origin. I trace the various physical processes that contribute to the growth of entropy, and conclude that gravitation holds the key to providing a comprehensive explanation of the elusive arrow. 1. Time's arrow versus the flow of time The subject of time's arrow is bedeviled by ambiguous or poor terminology and the con- flation of concepts. Therefore I shall begin my essay by carefully defining terms. First an uncontentious statement: the states of the physical universe are observed to be distributed asymmetrically with respect to the time dimension (see, for example, Refs. [1, 2, 3, 4]). A simple example is provided by an earthquake: the ground shakes and buildings fall down. We would not expect to see the reverse sequence, in which shaking ground results in the assembly of a building from a heap of rubble.