Toronto's Inner Suburbs Through the Lens of Planning History1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress on the Rexdale – Casino Woodbine Community Benefits

Attachment 9: Employment and Labour Market Advisory Working GroupEX11.1 Terms of 2 Reference Preamble Ontario Gaming GTA LP (OGGLP or "the Partnership") is committed to ensuring the Woodbine renewal is a force for positive change in the GTA – particularly for nearby neighbourhoods and for residents who are at a social or economic disadvantage. To this end, the Partnership has designed a 20-year Employment and Labour Market Plan that will align with the City’s ongoing work and exceed the Partnership’s already-strong practices across Canada to create thousands of high-quality jobs, establish valuable skills training programs, and facilitate equitable access to the unique opportunity afforded by redevelopment. Based on extensive discussions with City Staff and other stakeholders, the core of the Partnership’s Employment and Labour Market Plan is a collaborative approach to strengthening the employment pathway for local residents and equity-seeking groups. The Partnership’s core strength as a private sector job creator is hiring, training, and upskilling team members, with redevelopment and enhanced operations leading to increased labour market demand. Meanwhile, a strong cluster of City and social sector organizations are primarily focused on identifying, strengthening, and supporting a pool of candidates, with a focus on local residents, youth, and disadvantaged groups. When each player in this employment ecosystem is helping to build and strengthen program alignment, this plan will help to ensure that supply and demand connect. Through the Employment and Labour Market Advisory Working Group, OGGLP will work with the City of Toronto and key stakeholders in order to monitor inputs and outcomes and receive feedback that will allow its plans to be measured and strengthened. -

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

PERSPECTIVES on the INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival

PERSPECTIVES ON THE INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival L.S. Bourne Research Paper No. 94 Draft of a chapter for "The Geography of Modern Metropolitan Systems" Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, Columbia, Ohio Centre for Urban and Community Studies University of Toronto February 1978 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Objectives 3 2. WHAT AND WHERE IS THE INNER CITY? DEFINITIONS 5 AND CONCEPTS A Process Approach 6 A Problem Approach 9 3. DIVERSITY: THE CHANGING CHARACTER OF THE INNER CITY 14 Types of Inner City Neighborhoods 16 Social Disparities and the Inner City 20 Case Studies 25 4. WHY THE DECLINE OF THE INNER CITY? 30 The "Natural" Evolution Hypothesis 30 Preferences and Income: The "Pull" Hypothesis 32 The Obsolescence Hypothesis 35 The "Unintended" Policy Hypothesis 36 The Exploitation Hypothesis: Power, 40 Capitalism and the Political Economcy of Urbanization The Structural Change Hypothesis 43 The Fiscal Crisis and the Underclass Hypothesis 46 The Black Inner City in Cultural Isolation: 48 The Conflict Hypothesis Summary: Which Hypothesis of Decline is Correct? 51 5. BACK TO THE CITY: IS THE INNER CITY REVIVING? 55 6. CONCLUSIONS AND A LOOK AHEAD 63 Problems, Policies and Emerging Issues 66 Summary Comments 69 FOOTNOTES 71 REFERENCES 73 Preface The inner city is again a subject of widespread debate in most western countries. This paper undertakes to outline the nature of that debate and to document the reasons for inner city decline and revitalization. The argument is made that there is no single definition of the inner city which is universally ap plicable. -

Trailside Esterbrooke Kingslake Harringay

MILLIKEN COMMUNITY TRAIL CONTINUES TRAIL CONTINUES CENTRE INTO VAUGHAN INTO MARKHAM Roxanne Enchanted Hills Codlin Anthia Scoville P Codlin Minglehaze THACKERAY PARK Cabana English Song Meadoway Glencoyne Frank Rivers Captains Way Goldhawk Wilderness MILLIKEN PARK - CEDARBRAE Murray Ross Festival Tanjoe Ashcott Cascaden Cathy Jean Flax Gardenway Gossamer Grove Kelvin Covewood Flatwoods Holmbush Redlea Duxbury Nipigon Holmbush Provence Nipigon Forest New GOLF & COUNTRY Anthia Huntsmill New Forest Shockley Carnival Greenwin Village Ivyway Inniscross Raynes Enchanted Hills CONCESSION Goodmark Alabast Beulah Alness Inniscross Hullmar Townsend Goldenwood Saddletree Franca Rockland Janus Hollyberry Manilow Port Royal Green Bush Aspenwood Chapel Park Founders Magnetic Sandyhook Irondale Klondike Roxanne Harrington Edgar Woods Fisherville Abitibi Goldwood Mintwood Hollyberry Canongate CLUB Cabernet Turbine 400 Crispin MILLIKENMILLIKEN Breanna Eagleview Pennmarric BLACK CREEK Carpenter Grove River BLACK CREEK West North Albany Tarbert Select Lillian Signal Hill Hill Signal Highbridge Arran Markbrook Barmac Wheelwright Cherrystone Birchway Yellow Strawberry Hills Strawberry Select Steinway Rossdean Bestview Freshmeadow Belinda Eagledance BordeauxBrunello Primula Garyray G. ROSS Fontainbleau Cherrystone Ockwell Manor Chianti Cabernet Laureleaf Shenstone Torresdale Athabaska Limestone Regis Robinter Lambeth Wintermute WOODLANDS PIONEER Russfax Creekside Michigan . Husband EAST Reesor Plowshare Ian MacDonald Nevada Grenbeck ROWNTREE MILLS PARK Blacksmith -

City Planning Phone Directory

City Planning 1 City Planning City Planning provides advice to City Council on building issues. The division undertakes complex research projects, which lead to policy development in land use, environmental sustainability, community development, urban design and transportation. City Planning reviews development applications and recommends actions on these matters to Community Councils and the Planning and Transportation Committee. The division administers the Committee of Adjustment and provides expert planning advice to four Committee panels. Toronto City Hall Director 12th fl. E., 100 Queen St. W. Neil Cresswell ....................................... 394-8211 Toronto ON M5H 2N2 Administrative Assistant Annette Sukhai ...................................... 394-8212 Facsimile - General ..................................... 392-8805 Central Section (Wards 1, 2, 4, 6 – East of Royal York) - Chief Planner’s Office .............. 392-8115 Manager Bill Kiru ................................................. 394-8216 Administrative Assistant Chief Planner & Executive Director Kelly Allen ............................................ 394-8234 Jennifer Keesmaat ................................. 392-8772 Senior Planner Administrative Assistant Carly Bowman ....................................... 394-8228 Helen Skouras ........................................ 392-8110 Kathryn Thom ....................................... 394-8214 Adriana Suyck ....................................... 392-5217 Planner Program Manager Ellen Standret ....................................... -

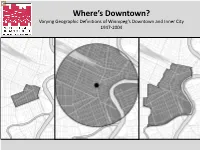

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

GTBL Champions

GTBL Champions: Year Winner Finalist Pennant 2019 Pickering Red Sox Thornhill Reds Newmarket Hawks 2018 Thornhill Reds Martingrove White Sox Thornhill Reds 2017 Pickering Red Sox Thornhill Reds Pickering Red Sox 2016 Thornhill Reds Pickering Red Sox Leaside Leafs 2015 Newmarket Hawks Pickering Red Sox East York Bulldogs 2014 Thornhill Reds East York Bulldogs Leaside Leafs 2013 Thornhill Reds East York Bulldogs Peterborough Riverdogs 2012 Leaside Leafs Martingrove White Sox Peterborough Riverdogs 2011 Markham Mariners Leaside Leafs Thornhill Reds 2010 Leaside Leafs Markham Mariners Leaside Leafs 2009 Leaside Leafs East York Bulldogs Oshawa Royals 2008 Leaside Leafs East York Bulldogs Oshawa Royals 2007 Leaside Leafs Thornhill Reds Leaside Leafs 2006 Newmarket Hawks Leaside Leafs Oshawa Royals 2005 East York Bulldogs Peterborough Riverdogs Peterborough Riverdogs 2004 Northumberland Whisky Jacks Newmarket Hawks Newmarket Hawks 2003 Thornhill Reds Newmarket Hawks 2002 Leaside Leafs Thornhill Reds 2001 Northumberland Whisky Jacks Leaside Leafs Northumberland Whisky Jacks 2000 Thornhill Reds North York Thunder North York Thunder 1999 North York Thunder 1998 North York Thunder Newmarket Hawks North York Thunder 1997 Etobicoke Rangers North York Shooters North York Shooters 1996 Etobicoke Rangers East York Bulldogs North York Shooters 1995 Leaside Leafs North York Shooters North York Shooters 1994 Etobicoke Rangers North York Shooters North York Shooters 1993 Etobicoke Rangers Leaside McSorley’s Etobicoke Rangers 1992 Etobicoke Indians North York -

Upscaling the Neighborhood

Upscaling the Neighborhood Nicole Stelle Garnett* Introduction................................................................................................................................................... 1 I. The Inner-Suburban “Problem” ........................................................................................................... 6 II. The Inner Ring as a Distributional Problem: The Regionalist Response ............................................ 9 III. The Inner-Ring as an Aesthetic Problem: The Land-Use Planning Response .............................. 11 IV. Upscaling in Action: A Cautionary Tale ........................................................................................ 18 A. Rule-of-Law Concerns .................................................................................................................... 19 B. Compliance Costs ........................................................................................................................... 24 C. The Trouble with the Transect ........................................................................................................ 26 D. Imposition of a Uniform Urban Aesthetic ...................................................................................... 28 E. The Lure of the Wrecking Ball ........................................................................................................ 32 V. The Political Economy of Inner-Suburban Land Use Regulation....................................................... 34 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................. -

The Demographic Transformation of Inner City Auckland

New Zealand Population Review, 35:55-74. Copyright © 2009 Population Association of New Zealand The Demographic Transformation of Inner City Auckland WARDLOW FRIESEN * Abstract The inner city of Auckland, comprising the inner suburbs and the Central Business District (CBD) has undergone a process of reurbanisation in recent years. Following suburbanisation, redevelopment and motorway construction after World War II, the population of the inner city declined significantly. From the 1970s onwards some inner city suburbs started to become gentrified and while this did not result in much population increase, it did change the characteristics of inner city populations. However, global and local forces converged in the 1990s to trigger a rapid repopulation of the CBD through the development of apartments, resulting in a great increase in population numbers and in new populations of local and international students as well as central city workers and others. he transformation of Central Auckland since the mid-twentieth century has taken a number of forms. The suburbs encircling the TCentral Business District (CBD) have seen overall population decline resulting from suburbanisation, as well as changing demographic and ethnic characteristics resulting from a range of factors, and some areas have been transformed into desirable, even elite, neighbourhoods. Towards the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty first century, a related but distinctive transformation has taken place in the CBD, with the rapid construction of commercial and residential buildings and a residential population growth rate of 1000 percent over a fifteen year period. While there are a number of local government and real estate reports on this phenomenon, there has been relatively little academic attention to its nature * School of Environment, The University of Auckland. -

Housing in the Evolving American Suburb Cover, from Top: Daybreak, South Jordan, Utah

Housing in the Evolving American Suburb Cover, from top: Daybreak, South Jordan, Utah. Daybreak, Utah St. Charles, Waldorf, Maryland. St. Charles Companies Inglenook, Carmel, Indiana. Ross Chapin Architects, Land Development & Building Inc. © 2016 by the Urban Land Institute 2001 L Street, NW Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036 Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher. Recommended bibliographic listing: Urban Land Institute. Housing in the Evolving American Suburb. Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute, 2016. ISBN: 978-0-87420-396-7 Housing in the Evolving American Suburb About the Urban Land Institute The mission of the Urban Land Institute is to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. ULI is committed to n Bringing together leaders from across the fields of real estate and land use policy to exchange best practices and serve community needs; n Fostering collaboration within and beyond ULI’s membership through mentoring, dialogue, and problem solving; n Exploring issues of urbanization, conservation, regeneration, land use, capital formation, and sustainable development; n Advancing land use policies and design practices that respect the uniqueness of both the built and natural environments; n Sharing knowledge through education, applied research, publishing, and electronic media; and n Sustaining a diverse global network of local practice and advisory efforts that address current and future challenges. Established in 1936, the ULI today has more than 39,000 members worldwide, representing the entire spectrum of the land use and development disciplines. -

Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus Between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability

sustainability Article Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability OndˇrejSlach, VojtˇechBosák, LudˇekKrtiˇcka* , Alexandr Nováˇcekand Petr Rumpel Department of Human Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, 709 00 Ostrava, Czechia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-731-505-314 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: Urban shrinkage has become a common pathway (not only) in post-socialist cities, which represents new challenges for traditionally growth-oriented spatial planning. Though in the post-socialist area, the situation is even worse due to prevailing weak planning culture and resulting uncoordinated development. The case of the city of Ostrava illustrates how the problem of (in)efficient infrastructure operation, and maintenance, in already fragmented urban structure is exacerbated by the growing size of urban area (through low-intensity land-use) in combination with declining size of population (due to high rate of outmigration). Shrinkage, however, is, on the intra-urban level, spatially differentiated. Population, paradoxically, most intensively declines in the least financially demanding land-uses and grows in the most expensive land-uses for public administration. As population and urban structure development prove to have strong inertia, this land-use development constitutes a great challenge for a city’s future sustainability. The main objective of the paper is to explore the nexus between change in population density patterns in relation to urban shrinkage, and sustainability of public finance. Keywords: Shrinking city; Ostrava; sustainability; population density; built-up area; housing 1. Introduction The study of the urban shrinkage process has ranked among established research areas in a number of scientific disciplines [1–7]. -

Towards Sustainable Urban Spatial Structure: Does Decentralization Reduce Commuting Times?

sustainability Article Towards Sustainable Urban Spatial Structure: Does Decentralization Reduce Commuting Times? Chunil Kim 1 and Choongik Choi 2,* 1 Housing Urban Finance Institute, Korea Housing & Urban Guarantee Corporation (HUG), BIFC, 40 Munhyeon-geumyung-ro, Nam-gu, Busan 48400, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Public Administration, Kangwon National University, 1, Gangwondaehak-gil, Chuncheon-si, Gangwon-do 24341, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-33-250-6813 Received: 31 December 2018; Accepted: 7 February 2019; Published: 15 February 2019 Abstract: This paper contributes to the existing debate on the co-location hypothesis, by devising a proximity measure and controlling for a set of other urban form measures. Utilizing the LEHD (Longitudinal Employer–Household Dynamics) Origin-Destination Employment Statistics (LODES) data that provide the number of jobs by a finer geography, this paper measured the degree of centralization, proximity, and job–housing mismatch. Multiple regression analysis revealed that the job–worker proximity leads to a shorter commuting time. In addition, the results focusing on suburban areas revealed that the impact of the job–worker imbalance and the impact of job–worker mismatch on the commuting time are greater in the suburb in comparison with the city center. Keywords: urban spatial structure; commuting; job–housing ratio; floating catchment area 1. Introduction The evolution of spatial structure plays a significant role in shaping interactions among decision-making agents in cities. The development of transportation technologies transformed old port city centers and connected inland areas to each other. As the railway system came into existence, firms that had been locked in the port center could move along the rail lines.