Día Tool Kit for Texas Librarians Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Giant Hummingbird from Paramo De Chingaza, Colombia.-On 10 October 1981, During an Ornithological Survey at 3250 M Elev

GENERAL NOTES 661 E. nigrivestis is timed to coincide with flowering of P. huigrensis (and other plants) which bloom seasonally at lower elevations. The general ecology of E. nigrivestis is similar to that recorded for the closely related species, the Glowing Puffleg (E. vextitus)(Snow and Snow 1980). Snow and Snow (1980) observed E. vestitus feeding principally at plants of similar general morphology (straight tubular corollas 10-20 mm in length) in similar taxonomic groups (Cnvenclishia; Ericaceae more often than Palicourea; Rubiaceae for E. vestitus). Territoriality in E. vestitus was pronounced while this was only suggested in the male E. nigrivestis we observed, perhaps a seasonal effect. Finally E. vestitus, like E. nigrivestis, did not occur in tall forested habitats at similar elevations (Snow and Snow [1980] study at 2400-2500 m). The evidence presented here suggests that the greatly restricted range of E. nigrivestis is not due to dietary specializations. Male nectar sources are from a broad spectrum of plants, and the principal food plant of both sexes, P. huigrensis, is a widespread Andean species. Nesting requirements of E. nigrivestis may still be threatened with extinction through habitat destruction, especially if the species requires specific habitats of natural vegetation at certain times of year, such as that found on nude ridge crests. The vegetation on nudes in particular is rapidly disappearing because nudes provide flat ground for cultivation in otherwise pre- cipitous terrain. In light of its restricted range and the threat of habitat destruction resulting from such close proximity to a major urban center, Quito, we consider E. -

WHEN MARK TWAIN WAS I Urged to Take out an Insurance Policy To

WHEN MARK TWAIN WAS I urged to take out an insurance policy to protect him from risk of accident while on the train trip for which he had just bought a ticket he declined, saying that he thought that instead he would take out a policy for the following day. The agent couldn't understand this, and Mark explained that he had been looking over the statistics and had discovered that by far the greatest number of accidents occurred to people while they were at home, so he concluded that it was more dangerous to stay at home than to travel. JUST NOW WE ARE Shocked by the number of deaths resulting from automobile accidents. Some statistician who has devoted considerable time to the subject compares automobile fatalities with deaths in war. According to his figures there were in the United States 388,936 deaths resulting directly from automobile accidents in the past fifteen years. And the record shows that in all the wars in which the United States has been engaged there were 244,357 American soldiers killed outright or fatally wounded on the field of battle. Probably Mark Twain would conclude that it is less dangerous to go to war than to ride in an automobile. BUT THAT IS NOT THE worst of it. It seems to be almost as dangerous to stay at home as it is to go joy-riding. In the year 1934 there were 36,000 persons killed by or in motor cars, and in the same year 34,500 persons were killed in accidents at home. -

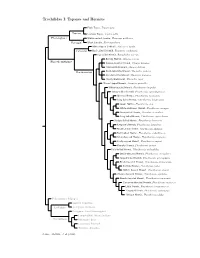

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Program PDF Saturday, March 28, 2020 Updated: 02-14-20

Program PDF Saturday, March 28, 2020 Updated: 02-14-20 Special ‐ Events and Meetings Congenital Heart Disease ‐ Scientific Session #5002 Session #602 Fellowship Administrators in Cardiovascular Education and ACHD Cases That Stumped Me Training Meeting, Day 2 Saturday, March 28, 2020, 8:00 a.m. ‐ 9:30 a.m. Saturday, March 28, 2020, 7:30 a.m. ‐ 5:30 p.m. Room S105b Marriott Marquis Chicago, Great Lakes Ballroom A CME Hours: 1.5 / CNE Hours: CME Hours: / CNE Hours: Co‐Chair: C. Huie Lin 7:30 a.m. Co‐Chair: Karen K. Stout Fellowship Administrators in Cardiovascular Education and Training Meeting, Day 2 8:00 a.m. LTGA, Severe AV Valve Regurgitation, Moderately Reduced EF, And Atrial Acute and Stable Ischemic Heart Disease ‐ Scientific Arrhythmia Session #601 Elizabeth Grier Treating Patients With STEMI: What They Didn't Teach You in Dallas, TX Fellowship! Saturday, March 28, 2020, 8:00 a.m. ‐ 9:30 a.m. 8:05 a.m. Room S505a ARS Questions (Pre‐Panel Discussion) CME Hours: 1.5 / CNE Hours: Elizabeth Grier Dallas, TX Co‐Chair: Frederick G. Kushner Co‐Chair: Alexandra J. Lansky 8:07 a.m. Panelist: Alvaro Avezum Panel Discussion: LTGA With AVVR And Reduced EF Panelist: William W. O'Neill Panelist: Jennifer Tremmel Panelist: Jonathan Nathan Menachem Panelist: Joseph A. Dearani 8:00 a.m. Panelist: Michelle Gurvitz Case of a Young Women With STEMI Panelist: David Bradley Jasjit Bhinder Valhalla, NY 8:27 a.m. ARS Questions (Post‐Panel Discussion) 8:05 a.m. Elizabeth Grier Young Women With STEMI: Something Doesn't Make Sense... -

Gene Duplication and the Evolution of Hemoglobin Isoform Differentiation in Birds

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Jay F. Storz Publications Papers in the Biological Sciences 11-2012 Gene Duplication and the Evolution of Hemoglobin Isoform Differentiation in Birds Michael T. Grispo University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Chandrasekhar Natarajan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Joana Projecto-Garcia University of Nebraska–Lincoln Hideaki Moriyama University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Roy E. Weber Aarhus University, Denmark See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscistorz Grispo, Michael T.; Natarajan, Chandrasekhar; Projecto-Garcia, Joana; Moriyama, Hideaki; Weber, Roy E.; and Storz, Jay F., "Gene Duplication and the Evolution of Hemoglobin Isoform Differentiation in Birds" (2012). Jay F. Storz Publications. 61. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscistorz/61 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jay F. Storz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Michael T. Grispo, Chandrasekhar Natarajan, Joana Projecto-Garcia, Hideaki Moriyama, Roy E. Weber, and Jay F. Storz This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ bioscistorz/61 Published in Journal of Biological Chemistry 287:45 (November 2, 2012), pp. 37647-37658; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.375600 Copyright © 2012 The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Inc. -

Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare-Conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens

Special Publications Museum of Texas Tech University Number xx76 19xx January XXXX 20212010 Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare-conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens Lisa A. Tell, Jenny A. Hazlehurst, Ruta R. Bandivadekar, Jennifer C. Brown, Austin R. Spence, Donald R. Powers, Dalen W. Agnew, Leslie W. Woods, and Andrew Engilis, Jr. Dedications To Sandra Ogletree, who was an exceptional friend and colleague. Her love for family, friends, and birds inspired us all. May her smile and laughter leave a lasting impression of time spent with her and an indelible footprint in our hearts. To my parents, sister, husband, and children. Thank you for all of your love and unconditional support. To my friends and mentors, Drs. Mitchell Bush, Scott Citino, John Pascoe and Bill Lasley. Thank you for your endless encouragement and for always believing in me. ~ Lisa A. Tell Front cover: Photographic images illustrating various aspects of hummingbird research. Images provided courtesy of Don M. Preisler with the exception of the top right image (courtesy of Dr. Lynda Goff). SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS Museum of Texas Tech University Number 76 Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) Research: Welfare- conscious Study Techniques for Live Hummingbirds and Processing of Hummingbird Specimens Lisa A. Tell, Jenny A. Hazlehurst, Ruta R. Bandivadekar, Jennifer C. Brown, Austin R. Spence, Donald R. Powers, Dalen W. Agnew, Leslie W. Woods, and Andrew Engilis, Jr. Layout and Design: Lisa Bradley Cover Design: Lisa A. Tell and Don M. Preisler Production Editor: Lisa Bradley Copyright 2021, Museum of Texas Tech University This publication is available free of charge in PDF format from the website of the Natural Sciences Research Laboratory, Museum of Texas Tech University (www.depts.ttu.edu/nsrl). -

Contents Contents

Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU CONTENTS CONTENTS PERU, THE NATURAL DESTINATION BIRDS Northern Region Lambayeque, Piura and Tumbes Amazonas and Cajamarca Cordillera Blanca Mountain Range Central Region Lima and surrounding areas Paracas Huánuco and Junín Southern Region Nazca and Abancay Cusco and Machu Picchu Puerto Maldonado and Madre de Dios Arequipa and the Colca Valley Puno and Lake Titicaca PRIMATES Small primates Tamarin Marmosets Night monkeys Dusky titi monkeys Common squirrel monkeys Medium-sized primates Capuchin monkeys Saki monkeys Large primates Howler monkeys Woolly monkeys Spider monkeys MARINE MAMMALS Main species BUTTERFLIES Areas of interest WILD FLOWERS The forests of Tumbes The dry forest The Andes The Hills The cloud forests The tropical jungle www.peru.org.pe [email protected] 1 Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU ORCHIDS Tumbes and Piura Amazonas and San Martín Huánuco and Tingo María Cordillera Blanca Chanchamayo Valley Machu Picchu Manu and Tambopata RECOMMENDATIONS LOCATION AND CLIMATE www.peru.org.pe [email protected] 2 Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU Peru, The Natural Destination Peru is, undoubtedly, one of the world’s top desti- For Peru, nature-tourism and eco-tourism repre- nations for nature-lovers. Blessed with the richest sent an opportunity to share its many surprises ocean in the world, largely unexplored Amazon for- and charm with the rest of the world. This guide ests and the highest tropical mountain range on provides descriptions of the main groups of species Pthe planet, the possibilities for the development of the country offers nature-lovers; trip recommen- bio-diversity in its territory are virtually unlim- dations; information on destinations; services and ited. -

Ecuador's Biodiversity Hotspots

Ecuador’s Biodiversity Hotspots Destination: Andes, Amazon & Galapagos Islands, Ecuador Duration: 19 Days Dates: 29th June – 17th July 2018 Exploring various habitats throughout the wonderful & diverse country of Ecuador Spotting a huge male Andean bear & watching as it ripped into & fed on bromeliads Watching a Eastern olingo climbing the cecropia from the decking in Wildsumaco Seeing ~200 species of bird including 33 species of dazzling hummingbirds Watching a Western Galapagos racer hunting, catching & eating a Marine iguana Incredible animals in the Galapagos including nesting flightless cormorants 36 mammal species including Lowland paca, Andean bear & Galapagos fur seals Watching the incredible and tiny Pygmy marmoset in the Amazon near Sacha Lodge Having very close views of 8 different Andean condors including 3 on the ground Having Galapagos sea lions come up & interact with us on the boat and snorkelling Tour Leader / Guides Overview Martin Royle (Royle Safaris Tour Leader) Gustavo (Andean Naturalist Guide) Day 1: Quito / Puembo Francisco (Antisana Reserve Guide) Milton (Cayambe Coca National Park Guide) ‘Campion’ (Wildsumaco Guide) Day 2: Antisana Wilmar (Shanshu), Alex and Erica (Amazonia Guides) Gustavo (Galapagos Islands Guide) Days 3-4: Cayambe Coca Participants Mr. Joe Boyer Days 5-6: Wildsumaco Mrs. Rhoda Boyer-Perkins Day 7: Quito / Puembo Days 8-10: Amazon Day 11: Quito / Puembo Days 12-18: Galapagos Day 19: Quito / Puembo Royle Safaris – 6 Greenhythe Rd, Heald Green, Cheshire, SK8 3NS – 0845 226 8259 – [email protected] Day by Day Breakdown Overview Ecuador may be a small country on a map, but it is one of the richest countries in the world in terms of life and biodiversity. -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

NORTHWEST & CENTRAL ANDES BIRDING PERU TRIP 19 Days Birding Trip

NORTHWEST & CENTRAL ANDES BIRDING PERU TRIP 19 Days Birding Trip (Private Tour) From September 03th to September 22th, 2017 BIRD GUIDE: Jesus Cieza PARTICIPANTS: Mr. Bob & Mrs. Marsha Rodrigues BIRDING LOCATIONS: Lima (Santa Eulalia – Villa Marshes – Pucusana) Ancash (Huascaran National Park – Conococha Lake - Yungay – Pueblo Libre) Huanuco (Bosque Unchog – Carpish Tunnel – Patty Trail) Junin (Junin Lake) ALTITUD AT BIRDING SITE: From sea level to 4600 m.a.s.l. SEPTEMBER 3RD We left Lima and took our own vehicle and drove pretty much the whole day moving according to our own pace, and having some stops along the highway including Conococha Lagoon. Of course we got some interesting birds as we ride and getting some cool landscape pictures as we bird. After this lovely ride we finally arrive to Yungay city, which is the closest little town to the main gate to Huascaran National Park. We stay at Rima Rima Hotel, a basic hotel with hot water and very nice people. We went to bed early to start our Ancash Birding Trip. Birds seen from Lima to Yungay. Variable Hawk, Giant Hummingbird, Rufous Naped Ground Tyrant (Muscisaxicola Pallidiceps), Crested Duck, Peruvian Sierra Finch, Mountain Caracara, American Kestrel, Austral Vermilion Flycatcher, Tropical Kingbird, West Peruvian Dove, Eared Dove, Long Tailed Mockingbird, Black Vulture, Turkey Vulture, Chiguanco Thrush, Chilean Flamingo, Grove Billed Ani, Cream winged Cinclodes, Giant Coot, Silvery Greebe, Yellow Billed teal, Andean Goose & Ash Breasted Sierra Finch. SEPTEMBER 04TH We started a little late 06:30 am but we managed to get the birds we wanted to see. We drove to the main gate of Huascaran National Park and we started our birding from there, gently walk along the National Park. -

LIFE and DOOM of the HUMMINGBIRD Billrecently Before the British House of Com by Rene Bache - 1 a Which Had Ill 1 the Lords, Pro So Disposed

;-> SUNDAY MAGAZINE FOR APRII 4 1909 . .... ;i and at turn he is met Chat's it!" says Bug, and more as l>i_^ as boned ham, every .... *<\u25a0;.!\u25a0- with the friendly smile. !!<• finds town a place we're bein' rolled up of the stone and this •\u25a0 maj be the Latin remarks. kind and sunny corners. He was just say; \\ liv. he's livii' of hearts he, < r "Well, Swell outl eh'" says Bui;, takin* was he want stayin' here long iilong here,"' says now! " ing how lie sorry But if Doc's struck as enough to get Utn-r acquainted with more of us Oh, Do r when he has the cash! Lei a }K>ep at the entrance. it when he's struck with a sudden spasm of memory lub he told \u25a0 to? Had rich as 1 susi>ect. this would just suit him. And if something to do with colk . he ain't here, Ireckon they ran put us or.hi- trail. great snakes!" says he, swattin' his knee Yon don't mean the Ui -I I'llrun in and see ." •\u25a0 lidn't stay All he found oat was WHYII- •\u25a0 I've plumb forgot He lon^. that about lookin' up old Hoc Keezar. Professor Keezar's name hadn't been on the list for Don't happen to know anybody ten years ick might try the telephone book," says I of that name," do you, Henry M. "-You Keezar? Hooj-er did; but there want a Keezar of any "No," says I. "\Vhal kind of description in it. -

Northern Peru and Huascarán National Park, Cordillera Blanca

Birding Ecotours Peru Birding Adventure: June 2012 Northern Peru and Huascarán National Park, Cordillera Blanca By Eduardo Ormaeche Yellow-faced Parrotlet (all photos by Ken Logan) TOTAL SPECIES: 507 seem, including 44 country endemics (heard only excluded) Itinerary Day 1, June 1st. Arrival in Lima and transfer to the hotel. Overnight Lima Day 2, June 2nd. Explore the Pucusana beach and Puerto Viejo wetlands. Overnight Lima Day 3, June 3rd. Explore the Lomas de Lachay National Reserve. Overnight Barranca Day 4, June 4th. Drive from Barranca to Huaraz. Explore Lake Conococha. Overnight Huaraz Day 5, June 5th. Explore Huascarán (Cordillera Blanca) National Park (Llanganuco Lake and Doña Josefa Trail). Overnight Huaraz Day 6, June 6th. Explore Huascarán National Park (Portachuelo de Huayhuash mountain pass). Overnight Huaraz Day 7, June 7th. Explore Pueblo Libre, Huaylas, and drive to the coast. Overnight Casma Day 8, June 8th. Drive from Casma to Trujillo. Explore Cerro Campana and Chan Chan archeological site. Overnight Trujillo Day 9, June 9th. Explore Sinsicap and drive to Chiclayo. Overnight Chiclayo Day 10, June 10th. Explore Bosque de Pómac Historical Sanctuary and drive towards Olmos. Overnight Bosque de Frejolillo (Quebrada Limón) safari camping Day 11, June 11th. Explore Bosque de Frejolillo and drive to Salas. Overnight Los Faiques Lodge Day 12, June 12th. Drive to the Porculla Pass and to Jaén. Overnight Jaén Day 13, June 13th. Explore the Gotas de Agua Private Reserve, visit the Huembo hummingbird center, drive to Pomacochas. Overnight Pomacochas Day 14, June 14th. Drive towards Abra Patricia. Overnight Long-whiskered Owlet Lodge (LWO) Day 15, June 15th.