World Heritage Papers 7 ; Cultural Landscapes: the Challenges Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Landscape Past of the Eastern Mediterranean: the Border Lord’S Gardens and the Common Landscape Tradition of the Arabic and Byzantine Culture

land Article The Cultural Landscape Past of the Eastern Mediterranean: The Border Lord’s Gardens and the Common Landscape Tradition of the Arabic and Byzantine Culture Konstantinos Moraitis School of Architecture, National Technical University of Athens (NTUA), 8A Hadjikosta Str., 11521 Athens, Greece; [email protected]; Tel.: +30-210-6434101 Received: 5 January 2018; Accepted: 21 February 2018; Published: 26 February 2018 Abstract: An evaluation of landscape tradition, in Near and Middle East area, could emphasize a profound past of agricultural experience, as well as of landscape and garden art. In reference to this common past, Byzantine and Arabic landscape and garden art paradigms appear to be geographically and culturally correlated, as proved by a Byzantine 12th century folksong, presenting the construction of a villa, with its surrounding gardens and landscape formations, in the territory of Euphrates River. This song refers to Vasilios Digenes Akritas or ‘Border Lord’, a legendary hero of mixed Byzantine-Greek and Arab blood; ‘Digenes’ meaning a person of dual genes, both of Byzantine and Arabic origin, and ‘Akritas’ an inhabitant of the borderline. At the end of the narration of the song, contemporary reader feels skeptical. Was modern landscape and garden art born in the European continent or was it transferred to Western world through an eastern originated lineage of Byzantine and Arabic provenance? Keywords: Arabic landscape and garden art; Byzantine landscape and garden art; cultural sustainability; political sustainability; Twain-born Border Lord 1. Introductory References: The Western Interest for Landscape and Its Eastern Precedents We ought to remark in advance that the present article is written by a professional design practitioner who believes, however, that space formative practices are not of mere technological importance. -

A Giant Hummingbird from Paramo De Chingaza, Colombia.-On 10 October 1981, During an Ornithological Survey at 3250 M Elev

GENERAL NOTES 661 E. nigrivestis is timed to coincide with flowering of P. huigrensis (and other plants) which bloom seasonally at lower elevations. The general ecology of E. nigrivestis is similar to that recorded for the closely related species, the Glowing Puffleg (E. vextitus)(Snow and Snow 1980). Snow and Snow (1980) observed E. vestitus feeding principally at plants of similar general morphology (straight tubular corollas 10-20 mm in length) in similar taxonomic groups (Cnvenclishia; Ericaceae more often than Palicourea; Rubiaceae for E. vestitus). Territoriality in E. vestitus was pronounced while this was only suggested in the male E. nigrivestis we observed, perhaps a seasonal effect. Finally E. vestitus, like E. nigrivestis, did not occur in tall forested habitats at similar elevations (Snow and Snow [1980] study at 2400-2500 m). The evidence presented here suggests that the greatly restricted range of E. nigrivestis is not due to dietary specializations. Male nectar sources are from a broad spectrum of plants, and the principal food plant of both sexes, P. huigrensis, is a widespread Andean species. Nesting requirements of E. nigrivestis may still be threatened with extinction through habitat destruction, especially if the species requires specific habitats of natural vegetation at certain times of year, such as that found on nude ridge crests. The vegetation on nudes in particular is rapidly disappearing because nudes provide flat ground for cultivation in otherwise pre- cipitous terrain. In light of its restricted range and the threat of habitat destruction resulting from such close proximity to a major urban center, Quito, we consider E. -

Cultural Heritage (Patrimony): an Introduction

Buckland: Cultural Heritage (Patrimony): An Introduction. Zadar, 2013. 1 Cultural Heritage (Patrimony): An Introduction. Preprint of: Cultural Heritage (Patrimony): An Introduction, pp 11-25 in: Records, Archives and Memory: Selected Papers from the Conference and School on Records, Archives and Memory Studies, University of Zadar, Croatia, May 2013. Ed. by Mirna Willer, Anne J. Gilliland and Marijana Tomić. Zadar: University of Zadar, 2015. ISBN 978-953-331-080-0. Published version may differ slightly. Michael Buckland School of Information, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Abstract Cultural heritage is important because it strongly influences our sense of identity, our loyalties, and our behavior. Memory institutions (archives, libraries, museums, schools, and historic sites) have a responsibility for preserving and interpreting the cultural record, so there are practical reasons to study cultural heritage. Attention to cultural heritage leads to wider awareness of the complexity and cultural bases of archives, libraries, and museums. Specialized terms are explained. The role of time is discussed and the past, history, and heritage are distinguished. Cultural heritage has some specialized legal and economic consequences and is deeply associated with much of the conflict and destruction in the world. Keywords Cultural heritage, Cultural policies, identity, Memory institutions, Collective memory Those who work in memory institutions (notably archives, libraries, museums, and historic sites) concern themselves with three distinct fields of study within the general theme of cultural heritage: 1. Culture: Examination of cultures and cultural heritages; 2. Techniques: The preservation, management, organization and interpretation of cultural heritage resources; and 3. Institutions: Study of those institutions that preserve, manage, organize, and interpret cultural heritage resources (and, indeed, to some extent define them) and their evolution over time. -

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

L'elicoide E Le Sue Applicazioni in Architettura Helicoid And

DISEGNARECON NUMERO SPECIALE DoCo 2012 – DoCUMENTAZIONE E CONSERVAZIONE DEL PATRIMONIO ARCHITETTONICO ED URBANO L’elicoide e le sue applicazioni in architettura Helicoid and Architectural application Laura Inzerillo, Engineering School, Department of Architecture, University of Palermo. Abstract Questo articolo è un risultato parziale di una ricerca riguardante la rappresentazione di superfici complesse in geometria descrittiva. La padronanza e l’abilità nell’uso delle diverse tecniche di rappresentazione, consente di raggiungere risultati che altrimenti non sarebbero perseguibili. La Scuola di Disegno di Ingegneria, dell’Università di Palermo si è da sempre fatta promotrice della scienza della rappresentazione attraverso la sperimentazione di tecniche semplificative ed innovative della geometria descrittiva applicata all’architettura e all’ingegneria. In particolar modo, in questo lavoro, si riporta lo studio di una superficie complessa quale è l’elicoide che trova larga applicazione nell’architettura. L’elicoide è qui trattata nella rappresentazione dell’assonometria ortogonale. Il metodo proposto è basato fondamentalmente sull’applicazione indispensabile ed imprescindibile dell’omologia. Alcuni passi, qui dati per scontato, trovano riscontro nei riferimenti bibliografici. This paper presents the issue of a long research on the representation of the complex surface in descriptive geometry. The ability to use the different techniques of representation aims to achieve results that you didn’t image before. In Palermo University, at the Engineering School, the researcher involved the study on the simplify of the so elaborated way to represent the geometry and its applications in architecture buildings and engineering implants. There is just report below the application methods to represent one of the most used surfaces in the practice of buildings. -

The Relationship Between Cultural Heritage Tourism and Historic Crafting & Textile Communities

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2012 The Relationship Between Cultural Heritage Tourism and Historic Crafting & Textile Communities Nyasha Brittany Hayes University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Hayes, Nyasha Brittany, "The Relationship Between Cultural Heritage Tourism and Historic Crafting & Textile Communities" (2012). Theses (Historic Preservation). 541. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/541 Suggested Citation: Hayes, Nyasha Brittany (2012). The Relationship Between Cultural Heritage Tourism and Historic Crafting & Textile Communities. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/541 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Relationship Between Cultural Heritage Tourism and Historic Crafting & Textile Communities Abstract The tourism industry continues to grow exponentially each year as many First and developing nations utilize its many subsets to generate commerce. Of the many types of tourism, arguably all countries employ heritage tourism as a method to protect their varying forms of cultural heritage , to establish national identities and grow their economies. As it is understood, to create a national identity a group of people will first identify what they consider to be the culturally significant eaturf es of their society that embodies their heritage. Heritage is a legacy that will be passed onto future generations that encompasses customs, expressions artifacts structures etc. This thesis will focus on the production of crafts and textiles as material culture for heritage tourism markets as a segment of cultural heritage. It will examine how the production of material culture is affected when it intersects with large scale heritage tourism. -

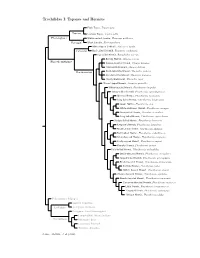

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Obtaining World Heritage Status and the Impacts of Listing Aa, Bart J.M

University of Groningen Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing Aa, Bart J.M. van der IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Aa, B. J. M. V. D. (2005). Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 Appendix 4 World heritage site nominations Listed site in May 2004 (year of rejection, year of listing, possible year of extension of the site) Rejected site and not listed until May 2004 (first year of rejection) Afghanistan Península Valdés (1999) Jam, -

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to Questions on Notice Environment Portfolio

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to questions on notice Environment portfolio Question No: 3 Hearing: Additional Estimates Outcome: Outcome 1 Programme: Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) Topic: Threatened Species Commissioner Hansard Page: N/A Question Date: 24 February 2016 Question Type: Written Senator Waters asked: The department has noted that more than $131 million has been committed to projects in support of threatened species – identifying 273 Green Army Projects, 88 20 Million Trees projects, 92 Landcare Grants (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3be28db4-0b66-4aef-9991- 2a2f83d4ab22/files/tsc-report-dec2015.pdf) 1. Can the department provide an itemised list of these projects, including title, location, description and amount funded? Answer: Please refer to below table for itemised lists of projects addressing threatened species outcomes, including title, location, description and amount funded. INFORMATION ON PROJECTS WITH THREATENED SPECIES OUTCOMES The following projects were identified by the funding applicant as having threatened species outcomes and were assessed against the criteria for the respective programme round. Funding is for a broad range of activities, not only threatened species conservation activities. Figures provided for the Green Army are approximate and are calculated on the 2015-16 indexed figure of $176,732. Some of the funding is provided in partnership with State & Territory Governments. Additional projects may be approved under the Natinoal Environmental Science programme and the Nest to Ocean turtle Protection Programme up to the value of the programme allocation These project lists reflect projects and funding originally approved. Not all projects will proceed to completion. -

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001. Preface This bibliography attempts to list all substantial autobiographies, biographies, festschrifts and obituaries of prominent oceanographers, marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and other scientists who worked in the marine environment published in journals and books after 1922, the publication date of Herdman’s Founders of Oceanography. The bibliography does not include newspaper obituaries, government documents, or citations to brief entries in general biographical sources. Items are listed alphabetically by author, and then chronologically by date of publication under a legend that includes the full name of the individual, his/her date of birth in European style(day, month in roman numeral, year), followed by his/her place of birth, then his date of death and place of death. Entries are in author-editor style following the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 14th ed., 1993). Citations are annotated to list the language if it is not obvious from the text. Annotations will also indicate if the citation includes a list of the scientist’s papers, if there is a relationship between the author of the citation and the scientist, or if the citation is written for a particular audience. This bibliography of biographies of scientists of the sea is based on Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre’s bibliography of biographies first published annually beginning with issue 4 of the History of Oceanography Newsletter (September 1992). It was supplemented by a bibliography maintained by Eric L. Mills and citations in the biographical files of the Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. -

Pictures of an Island Kingdom Depictions of Ryūkyū in Early Modern Japan

PICTURES OF AN ISLAND KINGDOM DEPICTIONS OF RYŪKYŪ IN EARLY MODERN JAPAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2012 By Travis Seifman Thesis Committee: John Szostak, Chairperson Kate Lingley Paul Lavy Gregory Smits Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter I: Handscroll Paintings as Visual Record………………………………. 18 Chapter II: Illustrated Books and Popular Discourse…………………………. 33 Chapter III: Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei: A Case Study……………………………. 55 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………. 78 Appendix: Figures …………………………………………………………………………… 81 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………………………………. 106 ii Abstract This paper seeks to uncover early modern Japanese understandings of the Ryūkyū Kingdom through examination of popular publications, including illustrated books and woodblock prints, as well as handscroll paintings depicting Ryukyuan embassy processions within Japan. The objects examined include one such handscroll painting, several illustrated books from the Sakamaki-Hawley Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, and Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei, an 1832 series of eight landscape prints depicting sites in Okinawa. Drawing upon previous scholarship on the role of popular publishing in forming conceptions of “Japan” or of “national identity” at this time, a media discourse approach is employed to argue that such publications can serve as reliable indicators of understandings -

Rethinking Maltese Legal Hybridity: a Chimeric Illusion Or a Healthy Grafted European Law Mixture? Kevin Aquilina

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Louisiana State University: DigitalCommons @ LSU Law Center Journal of Civil Law Studies Volume 4 Number 2 Mediterranean Legal Hybridity: Mixtures and Movements, the Relationship between the Legal Article 5 and Normative Traditions of the Region; Malta, June 11-12, 2010 12-1-2011 Rethinking Maltese Legal Hybridity: A Chimeric Illusion or a Healthy Grafted European Law Mixture? Kevin Aquilina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls Part of the Civil Law Commons Repository Citation Kevin Aquilina, Rethinking Maltese Legal Hybridity: A Chimeric Illusion or a Healthy Grafted European Law Mixture?, 4 J. Civ. L. Stud. (2011) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/jcls/vol4/iss2/5 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Law Studies by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RETHINKING MALTESE LEGAL HYBRIDITY: A CHIMERIC ILLUSION OR A HEALTHY GRAFTED EUROPEAN LAW MIXTURE? Kevin Aquilina* Abstract ....................................................................................... 261 I. Introduction ............................................................................. 262 II. The Nature of the Maltese Mixed Legal System.................... 263 III. The Nine Periods of Maltese Legal History ......................... 265 A. Roman Malta (218 B.C.-870) .............................................266 B. Arab Malta (870-1090)........................................................267 C. Norman Malta (1090-1530) ................................................268 D. Hospitallers Malta (1530-1798) ..........................................269 E. French Malta (1798-1800) ...................................................270 F. British Malta (1800-1964) ...................................................271 G.