What About Now? on the Symbolic Role of the Mudam in Luxembourg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fête Du Travail Et Des Cultures 2

#2 2019 | SUPPLÉMENT DE L'AKTUELL | FÊTE DU TRAVAIL ET DES CULTURESEntrée libre 1er MAI - Fête du travail et des cultures 2 Sortons pour le 1er mai! En 2019 se tient déjà la 14e édition de la fête du travail et des cultures de l’OGBL à Neimënster à Luxembourg-Ville. Cette fête, qui est organisée cette année une fois de plus en col- laboration avec le CCR Abbaye Neumünster, l’ASTI et l’ASTM, est devenue partie intégrante, non seulement du calendrier des événements syndicaux mais également de celui des évé- nements culturels de la capitale et du pays. Comme tous les ans, des milliers de femmes et d’hommes de toutes les couches de la population, d’origines différentes et de nationalités différentes, résidents et frontaliers vont participer à notre fête et assister à un programme culturel de qualité et varié qui s’adresse à tous les âges, jeunes et moins jeunes. Cette rencontre des cultures est aussi un témoignage en fa- veur de la mixité sociale et un gage du vivre ensemble dans la paix et la solidarité. Elle est donc également, de par son existence, en contradiction avec les forces en Europe, qui, au lieu de favoriser le vivre ensemble agitent le spectre de la différence, qui veulent l’armement au lieu de la paix et qui prônent l’égoïsme des nations au lieu de la solidarité. Ce n’est pas par hasard que ces mêmes forces s’opposent également aux droits syndicaux et, au-delà, aux droits démo- André Roeltgen Président de l'OGBL cratiques et aux libertés. -

Spaces and Identities in Border Regions

Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Culture and Social Practice Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Politics – Media – Subjects Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2015 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or uti- lized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: misterQM / photocase.de English translation: Matthias Müller, müller translations (in collaboration with Jigme Balasidis) Typeset by Mark-Sebastian Schneider, Bielefeld Printed in Germany Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-2650-6 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-2650-0 Content 1. Exploring Constructions of Space and Identity in Border Regions (Christian Wille and Rachel Reckinger) | 9 2. Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to Borders, Spaces and Identities | 15 2.1 Establishing, Crossing and Expanding Borders (Martin Doll and Johanna M. Gelberg) | 15 2.2 Spaces: Approaches and Perspectives of Investigation (Christian Wille and Markus Hesse) | 25 2.3 Processes of (Self)Identification(Sonja Kmec and Rachel Reckinger) | 36 2.4 Methodology and Situative Interdisciplinarity (Christian Wille) | 44 2.5 References | 63 3. Space and Identity Constructions Through Institutional Practices | 73 3.1 Policies and Normalizations | 73 3.2 On the Construction of Spaces of Im-/Morality. -

Communiqué De Presse

Communiqué de presse Etude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA LUXEMBOURG 2014/2015 Les résultats de la dixième édition de l’étude « TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA » réalisée par TNS ILRES et TNS MEDIA sont désormais disponibles. Cette étude qui informe sur l’audience des médias presse, radio, télévision, cinéma, dépliants publicitaires et Internet a été commanditée par les trois grands groupes de médias du pays: Editpress SA ; IP Luxembourg/CLT-UFA et Saint-Paul Luxembourg SA. L’étude a également été soutenue par le Gouvernement luxembourgeois. Depuis sa 1ère édition conduite en 2005-2006, l’étude Plurimédia était exclusivement réalisée moyennant un sondage téléphonique assisté par ordinateur (CATI). Considérant les évolutions de la société luxembourgeoise en matière d’usage des télécommunications et d’Internet, cette dixième édition de l’enquête est basée pour partie sur des enquêtes téléphoniques, pour une autre par Internet. L’objectif étant d’élargir la base de sondage et ainsi assurer une plus grande représentativité des résultats. L’étude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA a donc été réalisée auprès d’un échantillon aléatoire de 4.103 personnes (3.011 par téléphone, 1 092 par internet), représentatif de la population résidant au Grand-duché de Luxembourg, âgée de 12 ans et plus. Alors que la mesure d’audience des titres de presse se base sur l’univers des personnes âgées de 15 ans et plus, les résultats d’audience des autres médias se réfèrent supplémentairement sur l’univers 12+. Le terrain d’enquête s’est déroulé d’octobre 2014 à fin mai 2015. Ci-après, vous trouverez quelques chiffres clés, concernant le lectorat moyen par période de parution, c’est-à-dire le lectorat par jour moyen pour les quotidiens, le lectorat par semaine moyenne pour les hebdomadaires, et ainsi de suite. -

Iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii

IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Philharmonie Luxembourg Salle de Concerts Grande-Duchesse Joséphine-Charlotte Saison 2008/09 1 Partenaires d’événements: Nous remercions nos partenaires qui en Partenaires de programmes: associant leur image à la Philharmonie et en soutenant sa programmation, permettent sa diversité et l’accès à un public plus large. pour «Jeunes publics» pour «Backstage» Partenaires média: Partenaires officiels: 2 Sommaire / Inhalt / Content IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Philharmonie Luxembourg Jazz, World & Easy listening Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg Cycle Philharmonique I 140 Salle de Concerts Grande-Duchesse Jazz & beyond 66 Cycle Philharmonique II 142 Joséphine-Charlotte – Saison 2008/09 Autour du monde 74 Amis de l’Orchestre Philharmonique du Ciné-Concerts 80 Luxembourg 144 Bienvenue / Willkommen / Welcome 4 Pops 84 Chill at the Phil 88 Solistes Européens, Luxembourg 146 European Music Academy, Schengen 150 Soirées de Luxembourg 152 IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Orchestre Special «Les Musiciens» – Orchestre de Chambre du Luxembourg 154 Grands orchestres 16 Luxembourg Festival 94 Grands solistes 20 Musiques d’aujourd’hui 96 L’Orchestral 24 On the border -

ARNY SCHMIT (Luxembourg, 1959)

ARNY SCHMIT (Luxembourg, 1959) Arny Schmit is a storyteller, a conjurer, a traveler of time and space. From the myth of Leda to the images of an exhibitionist blogger, from the house of a serial killer to the dark landscapes of a Caspar David Friedrich, he makes us wander through a universe that tends towards the sublime. Manipulating the mimetic properties of painting while referring to the virtual era in which we live, the Luxembourgish artist likes to surprise by playing on the false pretenses. In his paintings he creates bridges between reality, fantasy and nightmare. The medieval, baroque or romantic references reveal his profound respect for the masters of the past. Extracted from a different time era, decorative motifs populate his compositions like so many childhood memories, from the floral wallpaper to the dusty Oriental carpet, through the models of embroidery. Through fragmentation, juxtaposition and collage, Arny Schmit multiplies the reading tracks and digs the strata of the image. The beauty of his women contrasts with their loneliness and sadness, the enticing colors are soiled with spurts, the shapes are torn to reveal the underlying, the reverse side of the coin, the unknown. 1 EXHIBITION – DECEMBER 1st, 2018 to FEBRUARY 28th, 2019 ARNY SCHMIT – WILD 13 windows with a view on the wilderness. Recent works by Luxembourgish painter Arny Schmit depict his vision of a daunting and nurturing nature and its relationship with the female body. A body that Schmit likes to fragment by imprisoning it into frames of analysis, each frame a clue into a mysterious narrative, a suggestion, an impression. -

Saison 2018/19 Numéro De Client / Kundennummer / Client Number Nouvel Abonné / Neuer Abonnent / New Subscriber

Commande d’abonnement / Abo-Bestellung / Order a subscription Nom / Nachname / Last name Prénom / Vorname / First name Rue/No / Straße/Nr. / Street/No. Code postal/Localité / PLZ/Ort / Postal code/City Tel e-mail Saison 2018/19 Numéro de client / Kundennummer / Client number Nouvel abonné / Neuer Abonnent / New subscriber Tarif réduit / Ermäßigter Preis / Reduced price Moins de 27 ans / Unter 27 Jahre / Under 27 years: Je joins une copie de ma carte d’identité. Ich lege eine Kopie meines Personalausweises bei. I attach a copy of my ID card. Paiement / Bezahlung / Payment Mastercard Visa / No carte de credit / Kreditkartennummer / credit card number valable jusqu’au / gültig bis / valid until S’il n’y a plus de places dans la catégorie choisie, je préfère une catégorie supérieure inférieure Sollte es keine verfügbaren Plätze in der gewünschten Kategorie geben, bevorzuge ich eine höhere niedrigere Kategorie Should there be no seats left in the chosen category, I prefer a higher lower category 2018/19 Lieu, date / Ort, Datum / City, date Signature / Unterschrift / Signature Saison 1 MBS8041468_RiskAnAffair_S coupé&cabrio_148x190mm_LU_v02vector.indd 1 15/03/2018 17:52 Établissement public Salle de Concerts Grande-Duchesse Joséphine-Charlotte Philharmonie Luxembourg Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg Saison 2018/19 Nous remercions nos partenaires qui, Partenaires de la saison: en associant leur image à la Philharmonie et à l’Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg et en soutenant leur programmation, permettent leur diversité et l’accès à -

Notice Philatélique D'un Timbre

http://www.wikitimbres.fr V2010.pdf Wercollier Luxembourg w ,...,..-----~------, '::::! ...- ....-- Œuvre originale créée spécialement pour le timbre-poste par Lucien Wercollier Mise en page de Michel Durand-Mégret w => a Imprimé en héliogravure ---' co Format horizontal 48 x 36,85 => CL -cr:w '--____ .....,.._ "--____ _ 30 timbres à la feuille LA POSTE WERCOLLIER Vente anticipée le 20 janvier 1996 6,70 1996 LUXEMBOURG à Strasbourg (Bas-Rhin) Vente générale le 22 janvier 1996 Né en 1908, à Luxembourg, le sculpteur sculpturales pour le pavillon luxembour et de dialoguer entre elles. Par ailleurs, la Lucien Wercollier a bénéficié d'une forma geois de l'Exposition universelle de perfection du bronze poli à l'extrême et les tion académique extrêmement poussée. Bruxelles en 1958. La même année, il expo effets colorés susceptibles de se dégager Il est tout d'abord élève à l'Académie des se à titre personnel et pour la première fois d'une masse de pierre choisie avec le plus beaux-arts de Bruxelles puis se rend à Paris ses œuvres abstraites à la galerie Saint grand soin, permettent au sculpteur d'ajou où il suit les cours de l'Ecole nationale des Augustin à Paris. Qu'il choisisse de s'expri ter à cet échange subtil qu'il sait instaurer beaux-arts. Ses premiers travaux sont d'ins mer par le bronze, qu 'il travaille le marbre entre sa vision et les formes qui en émer piration naturaliste et témoignent des ou l'albâtre, qu'il trace dans l'espace d'une gent, toute une gamme de vibrations sen influences successives d'Aristide Maillol et feuille blanche un ensemble de lignes mul sibles dues aux jeux de la lumière remar d'Henri Laurens. -

Iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii

IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Philharmonie Luxembourg Salle de Concerts Grande-Duchesse Joséphine-Charlotte Saison 2010/11 1 Sommaire / Inhalt / Content Partenaires d’événements: IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Philharmonie Luxembourg Jazz, World & Easy listening Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg Cycle Philharmonique I 150 Salle de Concerts Grande-Duchesse Jazz & beyond 68 Cycle Philharmonique II 152 Joséphine-Charlotte – Saison 2010/11 Autour du monde 76 Cycle «Dating:» 154 Ciné-Concerts 82 Cycle «Duo» 155 Bienvenue / Willkommen / Welcome 4 Pops 86 Cycle «Familles» 156 Chill at the Phil 90 Amis de l’Orchestre Philharmonique du Nous remercions nos partenaires qui, en IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Luxembourg 158 associant leur image à la Philharmonie et Orchestre IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Solistes Européens, Luxembourg en soutenant sa programmation, permettent Special Cycle Rencontres SEL A 160 sa diversité et l’accès à un public plus large. Partenaire de programme: Grands orchestres 14 Cycle Rencontres SEL B 162 Grands solistes 18 Luxembourg Festival 96 Camerata 164 L’Orchestral 22 back to the future – rainy days 2010 98 Soirées de Luxembourg 166 pour «Backstage» Concerts exceptionnels 26 Musiques d’aujourd’hui -

MEDIA GUIDE XII Ministerial Meeting EU-Rio Group 26-27 May 2005 Luxembourg-Kir Chberg

MEDIA GUIDE XII Ministerial Meeting 26-27 May 2005 EU-Rio Group Luxembourg-Kirchberg .eu2005.lu www Welcome Note I would like to wish you a warm welcome in Luxembourg for the 12th Ministerial Meeting between the European Union and the Rio Group which will further deepen the intense and fruitful contacts which the European Union and its Member States maintain with the Latin-American continent. The Rome Declaration of 20 December 1990 has institutio- nalised the relations between the European Union and the Rio Group and has given birth to a forum of dialogue between both our regions which, through their historical ties, share common values and a common cultural heritage. Here in Luxembourg, in April 1991, was held the first Ministerial Meeting assembling 12 countries of the Euro- pean Community and 11 countries of the Rio Group. We are given the occasion today to look back on the roots of our partnership. Our meeting will enable us to assess the results of the last fourteen years, during which both regions continuously enlarged and strengthened in order to be able to face the challenges confronting our societies nowadays. I am very pleased about all the joint efforts undertaken in the promotion of our common values, notably in democracy, human rights, good governance and social cohesion. •••1 Our meeting here in Luxembourg will give us the oppor- tunity to discuss the future of our relations even further in order to reinforce our ties of cooperation and friendship that bond us already. I have no doubt that our discussions will be fruitful and wish you a pleasant stay in my country! Jean Asselborn Deputy Prime Minister, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Immigration •••2 Content A Media Programme 5 Formal programme 5 Media arrangements 5 B Kiem Conference Centre 7 1. -

51% 49% 71% 16% 16%

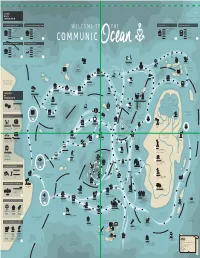

THE WAY WE USE MERKUR - INF OGRAPHIC - C OMMUNICOCEAN - MA Y/JUNE 2015 COMMUNICATION USE OF DAILY NEWSPAPERS (TOP 5) USE OF WEEKLY & BI MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF TV-STATIONS USE OF WEB-SITES (TOP 5) 39,0% LUXEMBURGER WORT 32,8% AUTOTOURING 25,2% RTL TELE LETZEBUERG 25,7% RTL.LU 29,5% L´ESSENTIEL 14,3% AUTO REVUE 3,8% NORDLIICHT TV 16,9% WORT.LU 9,3% TAGEBLATT 13,9% AUTOMOTO 2,1% CHAMBER TV 11,3% L´ESSENTIEL.LU 5,7% LE QUOTIDIEN 11,3% PAPERJAM ... ... 9,2% PUBLIC.LU 2,1% LETZEBUERGER JOURNAL 9,6% CITY MAG ... ... 4,7% TAGEBLATT.LU USE OF MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF RADIO-SATIONS (TOP 5) 23,0% TÉLÉCRAN 36,8% RTL RADIO LETZEBUERG 17,0% LUX-POST WEEK-END 19,6% ELDORADIO 15,7% REVUE 8,5% RTL (GERMAN LANGUAGE) 12,1% CONTACTO 5,4% RADIO LATINA 7,7% LUXBAZAR 4,5% RADIO 100,7 NEW IDEA PRINT MEDIA STORY TELLING 2010s - PRINT NATIVE IN DANGER ADVERTISING MESSENGERS SEA OF PRINT CREATIVITY TRENDY COAST TEXTUAL C ONTENT FRESH IDEAS ISLANDS BUSINESS PLAN FREE NEW SPAPER INFOGRAPHICS 2007 - 1st ISSUE OF L’ESSENTIEL BIG BUDGET FEE / DUTY MAGAZINE MESSENGERS DATA 1932 - 1st MA GAZINE VISUALIZATION CONTINENT AUTOTOURING BY CONSEIL DE AUTOMOBILE CLUB PRESSE M PICTURES A NEWSPAPER I 1848 - 1st ISSUE OF N PRINTING NEWSPAPER RACING PIGE ON LUXEMBURGER WORT S THE HISTORY 1900s - 1st ME CHANIC 1913 - 1st ISSUE 776 B.C. - WINNER LIST COMPUTER PRINTER OF TAGEBLATT LOW BUDGET T OF OF OLYMPIC GAMES SENT R COMMUNICATION BY DOVES E AGE A LANGUAGE B ARRIER REEF NATIO- M NALITY 70,5% LUXEMBOURGISH N E W S P A P E R 55,7% FRENCH GENDER PROF- A REVOLUTION BEGAN 1650 - 1st DAILY 30,6% GERMAN ESSION AS MANKIND STARTED NEWSPAPER 21,0% ENGLISH TO BIND MESSAGES 20,0% PORTUGUESE TO TIME & TO SPACE BIG BUDGET CONSEIL DE HOBBIES PUBLICITÉ INCOME EDU- CLIENTS FUN CATION COAST HOW DID THEY DO THIS ? PRINT R OUTE REPRODUCTION CLIENTS 1450 - GUTENBER G EMOTIONS BUDGET INVENTS PRINT LETTERS COAST CONFUSION TELEVISION TRIANGLE TIME BINDING DEFINITION 1970 - ST ART OF TV-SPOT VISUAL 30.000 B.C. -

Rédacteurs En Chef De La Presse Luxembourgeoise 93

Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Agenda Plurionet Frank THINNES boulevard Royal 51 L-2449 Luxembourg +352 46 49 46-1 [email protected] www.plurio.net agendalux.lu BP 1001 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 42 82 82-32 [email protected] www.agendalux.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Hebdomadaires d'Lëtzeburger Land M. Romain HILGERT BP 2083 L-1020 Luxembourg +352 48 57 57-1 [email protected] www.land.lu Woxx M. Richard GRAF avenue de la Liberté 51 L-1931 Luxembourg +352 29 79 99-0 [email protected] www.woxx.lu Contacto M. José Luis CORREIA rue Christophe Plantin 2 L-2988 Luxembourg +352 4993-315 [email protected] www.contacto.lu Télécran M. Claude FRANCOIS BP 1008 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 4993-500 [email protected] www.telecran.lu Revue M. Laurent GRAAFF rue Dicks 2 L-1417 Luxembourg +352 49 81 81-1 [email protected] www.revue.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Correio Mme Alexandra SERRANO ARAUJO rue Emile Mark 51 L-4620 DIfferdange +352 444433-1 [email protected] www.correio.lu Le Jeudi M. Jacques HILLION rue du Canal 44 L-4050 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 22 05 50 [email protected] www.le-jeudi.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Quotidiens Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek M. Ali RUCKERT - MEISER rue Zénon Bernard 3 L-4030 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 446066-1 [email protected] www.zlv.lu Le Quotidien M. -

NY - LUX Page Musée D’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean ESAL 2004-2014 1

Mudam Luxembourg NY - LUX Page Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean ESAL 2004-2014 1 NY - LUX EDWARD STEICHEN AWARD 2004-2014 14/02/2014 - 09/06/2014 PRESS kIT MUDAM LUXEMBOURG Étienne Boulanger. Shots, 2004–2006. © Photo: ENSA Nancy mudaM Mudam Luxembourg NY - LUX Page Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean ESAL 2004-2014 2 NY - LUX EDWARD STEICHEN AWARD 2004-2014 PRESS RELEASE ADDRESS AND INfORMATION EDWARD STEICHEN AWARD LUXEMBOURG 2005 - SU-MEI TSE 2007 - éTIENNE BOULANGER 2009 - BERTILLE BAk 2011 - MARIA LOBODA 2013 - SOPHIE JUNG EDWARD STEICHEN LUXEMBOURG RESIDENT IN NEW YORk 2011 - CLAUDIA PASSERI 2013 - JEff DESOM CONTEMPORARY ART AWARDS ISCP - INTERNATIONAL STUDIO & CURATORIAL PROGRAM EDWARD STEICHEN - BIOGRAPHY Mudam Luxembourg NY - LUX Page Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean ESAL 2004-2014 3 Press release NY - LUX EDWARD STEICHEN AWARD 2004-2014 Exhibition from 14 February to 9 June 2014 Artists Bertille Bak, Étienne Boulanger, Jeff Desom, Sophie Jung, Maria Loboda, Claudia Passeri, Su-Mei Tse Curator Enrico Lunghi The exhibition NY–LUX. Edward Steichen Award 2004-2014 features the seven laureates of the Edward Steichen Award Luxembourg, revealing in seven monographic presentations about 40 recent artworks representative of the development of their respective career. The Edward Steichen Award Luxembourg was founded in 2004 in memory of the eponymous American photographer and museum curator (born in 1879 in Bivange, Luxembourg) with the aim to stimulate the dialogue between the artistic scenes of Europe and the United States – a dialogue that Steichen himself helped to initiate at the outset of the 20th century. This biennial prize, which is awarded by an international jury to an artist from Luxembourg or the Greater Region, rewards its winner with a six-month residency in New York in the framework of the prestigious International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP).