Hispanic Reflections on the American Landscape Identifying and Interpreting Hispanic Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Latin(O) Americanos: Transoceanic Diasporas And

DEBATES: GLOBAL LATIN(O) AMERICANOS Global Latin(o) Americanos: Transoceanic Diasporas and Regional Migrations by MARK OVERMYER-VELÁZQUEZ | University of Connecticut | [email protected] and ENRIQUE SEPÚLVEDA | University of Saint Joseph, Connecticut | [email protected] Human mobility is a defining characteristic By the end of the first decade of the Our use of the term “Global Latin(o) of our world today. Migrants make up one twenty-first century the contribution of Americanos” places people of Latin billion of the globe’s seven billion people— Latin America and the Caribbean to American and Caribbean origin in with approximately 214 million international migration amounted to over comparative, transnational, and global international migrants and 740 million 32 million people, or 15 percent of the perspectives with particular emphasis on internal migrants. Historic flows from the world’s international migrants. Although migrants moving to and living in non-U.S. Global South to the North have been met most have headed north of the Rio Grande destinations.5 Like its stem words, Global in equal volume by South-to-South or Rio Bravo and Miami, in the past Latin(o) Americanos is an ambiguous term movement.1 Migration directly impacts and decade Latin American and Caribbean with no specific national, ethnic, or racial shapes the lives of individuals, migrants have traveled to new signification. Yet by combining the terms communities, businesses, and local and destinations—both within the hemisphere Latina/o (traditionally, people of Latin national economies, creating systems of and to countries in Europe and Asia—at American and Caribbean origin in the socioeconomic interdependence. -

Latino Unemployment Rate Remains the Highest at 17.6% Latina Women Are Struggling the Most from the Economic Fallout

LATINO JOBS REPORT JUNE 2020 Latino Unemployment Rate Remains the Highest at 17.6% Latina women are struggling the most from the economic fallout LEISURE AND HOSPITALITY EMPLOYMENT LEADS GAINS, ADDING 1.2 MILLION JOBS In April, the industry lost 7.5 million jobs. Twenty-four percent of workers in the leisure and hospitality industry are Latino. INDICATORS National Latinos Employed • Working people over the age of 16, including 137.2 million 23.2 million those temporarily absent from their jobs Unemployed • Those who are available to work, trying to 21 million 5 million find a job, or expect to be called back from a layoff but are not working Civilian Labor Force 158.2 million 28.2 million • The sum of employed and unemployed people Unemployment Rate 13.3% 17.6 % • Share of the labor force that is unemployed Labor Force Participation Rate • Share of the population over the age of 16 60.8% 64.1% that is in the labor force Employment-Population Ratio • Share of the population over the age of 16 52.8% 52.8% that is working Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Status of the Hispanic or Latino Population by Sex and Age,” Current Population Survey, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf (accessed June 5, 2020), Table A and A-3. www.unidosus.org PAGE 1 LATINO JOBS REPORT Employment of Latinos in May 2020 The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) reported that employers added 2.5 million jobs in May, compared to 20.5 million jobs lost in April. -

Biocultural Design” As a Framework to Identify Sustainability Issues in Río San Juan Biosphere Reserve and the Fortress of the Immaculate Conception, Nicaragua

“Biocultural design” as a framework to identify sustainability issues in Río San Juan Biosphere Reserve and the Fortress of the immaculate Conception, Nicaragua Claudia Múnera-Roldán Final Report for the UNESCO MaB Young Scientists Awards 2013-2014 “Biocultural design” as a framework to identify sustainability issues in Río San Juan Biosphere Reserve and the Fortress of the immaculate Conception, Nicaragua Claudia Múnera-Roldán Final Report for the UNESCO MaB Young Scientists Awards 2013-2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................................. 4 List of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Executive summary............................................................................................................................................ 6 1. Introduction: Site identification and context analysis .................................................................................. 8 1.1 Site description ............................................................................................................................................ 8 1.2. Context and background ........................................................................................................................... -

Communicating with Hispanic/Latinos

Building Our Understanding: Culture Insights Communicating with Hispanic/Latinos Culture is a learned system of knowledge, behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, values, and norms that is shared by a group of people (Smith, 1966). In the broadest sense, culture includes how people think, what they do, and how they use things to sustain their lives. Cultural diversity results from the unique nature of each culture. The elements, values, and context of each culture distinguish it from all others (Beebe, Beebe, & Redmond, 2005). Hispanics in the United States includes any person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race. Latinos are people of “Latin-American” descent (Webster’s 3rd International Dictionary, 2002). Widespread usage of the term “Hispanic” dates back to the 1970s, when the Census asked individuals to self-identify as Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central/South American or “other Hispanic.” While the terms Hispanic and Latino are used interchangeably, they do have different connotations. The Latino National Survey (2006) found that 35% of respondents preferred the term “Hispanic,” whereas 13.4% preferred the term “Latino.” More than 32% of respondents said either term was acceptable, and 18.1% indicated they did not care (Fraga et al., 2006). Origin can be viewed as the heritage, nationality group, lineage, or country of birth of the person or the person’s parents or ancestors before their arrival in the United States (U. S. Census Bureau, 2000). People who identify their origin as Spanish, Hispanic, or Latino may be of any race (Black/African-American, White/Caucasian, Asian, and Native American) or mixed race. -

Overview Print Page Close Window

World Directory of Minorities Americas MRG Directory –> Cuba –> Cuba Overview Print Page Close Window Cuba Overview Environment Peoples History Governance Current state of minorities and indigenous peoples Environment Cuba is the largest island in the Caribbean. It is located 150 kilometres south of the tip of the US state of Florida and east of the Yucatán Peninsula. On the east, Cuba is separated by the Windward Passage from Hispaniola, the island shared by Haiti and Dominican Republic. The total land area is 114,524 sq km, which includes the Isla de la Juventud (formerly called Isle of Pines) and other small adjacent islands. Peoples Main languages: Spanish Main religions: Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant), syncretic African religions The majority of the population of Cuba is 51% mulatto (mixed white and black), 37% white, 11% black and 1% Chinese (CIA, 2001). However, according to the Official 2002 Cuba Census, 65% of the population is white, 10% black and 25% mulatto. Although there are no distinct indigenous communities still in existence, some mixed but recognizably indigenous Ciboney-Taino-Arawak-descended populations are still considered to have survived in parts of rural Cuba. Furthermore the indigenous element is still in evidence, interwoven as part of the overall population's cultural and genetic heritage. There is no expatriate immigrant population. More than 75 per cent of the population is classified as urban. The revolutionary government, installed in 1959, has generally destroyed the rigid social stratification inherited from Spanish colonial rule. During Spanish colonial rule (and later under US influence) Cuba was a major sugar-producing territory. -

Areas and Periods of Culture in the Greater Antilles Irving Rouse

AREAS AND PERIODS OF CULTURE IN THE GREATER ANTILLES IRVING ROUSE IN PREHISTORIC TIME, the Greater Antilles were culturally distinct, differingnot only from Florida to the north and Yucatan to the west but also, less markedly,from the Lesser Antilles to the east and south (Fig. 1).1 Within this major provinceof culture,it has been customaryto treat each island or group FIG.1. Map of the Caribbeanarea. of islands as a separatearchaeological area, on the assumptionthat each contains its own variant of the Greater Antillean pattern of culture. J. Walter Fewkes proposedsuch an approachin 19152 and worked it out seven years later.3 It has since been adopted, in the case of specific islands, by Harrington,4Rainey,5 and the writer.6 1 Fewkes, 1922, p. 59. 2 Fewkes, 1915, pp. 442-443. 3 Fewkes, 1922, pp. 166-258. 4 Harrington, 1921. 5 Rainey, 1940. 6 Rouse, 1939, 1941. 248 VOL. 7, 1951 CULTURE IN THE GREATERANTILLES 249 Recent work in connectionwith the CaribbeanAnthropological Program of Yale University indicates that this approach is too limited. As the distinction between the two major groups of Indians in the Greater Antilles-the Ciboney and Arawak-has sharpened, it has become apparent that the areas of their respectivecultures differ fundamentally,with only the Ciboney areas correspond- ing to Fewkes'conception of distributionby islands.The Arawak areascut across the islands instead of enclosing them and, moreover,are sharply distinct during only the second of the three periods of Arawak occupation.It is the purpose of the presentarticle to illustratethese points and to suggest explanationsfor them. -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

La Historia Detrás De La Pared De Piedra

21 al 27 de septiembre del 2014 • www.laprensalatina.com Variedades • Entertainment 15 Cementerio y Funeraria Memorial Park… La Gruta del La historia detrás de la pared de piedra Santuario Memorial Park Funeral Home and Cemetery… The Story Behind the Stone Wall de Cristal The Crystal Shrine Grotto MEMPHIS, TN (LPL) --- La Gruta del Santuario de Cristal es la úni- ca cueva en el mundo hecha por el hombre y está situada en el interior del Cementerio “Memorial Park” en Memphis, TN. El artista y arquitecto Dionisio Rodríguez diseñó y creó la cueva a lo largo de diez años, a partir de 1938. Dionisio Rodríguez (1891-1955) de Toluca, México, fue un artista muy popular por su estilo único de transformar el cemento (concreto) en fantásticas obras de arte, que en realidad parecían ser esculpidas en madera; su técnica era conocida como Faux Bois (madera falsa en francés). Las puertas, los bancos y las formaciones de rocas artificiales fueron creadas por el artista para in- vitar a los visitantes a descansar o explorar el paisaje. Rodríguez calificaba su trabajo como “el método rústico”. Dentro de la gruta hay diez esce- nas que representan la vida de Jesu- cristo. Estas escenas fueron realiza- das con una técnica mixta de pintura y escultura. La cueva ofrece un ambiente tranquilo, tanto que quienes la visi- tan sienten una gran paz y aprecian su belleza y valor artístico. Las esculturas de Rodríguez y el Santuario de la Gruta de Cristal en el Cementerio Memorial Park están incluidas en el Registro Nacional de Lugares Históricos. -

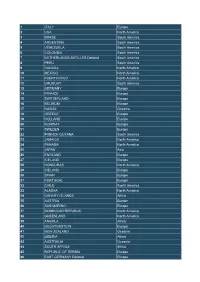

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

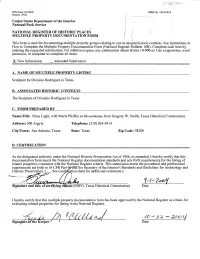

I Sculpture by Dionicio Rodriguez in Texas

NFS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) R _, , United States Department of the Interior { \ National Park Service iI • NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES 1 1 f MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM \ I 1 ' ' - ; '^v '- This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one oc^several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. NAME OF MULTIPLE PROPERTY LISTING Sculpture by Dionicio Rodriguez in Texas B. ASSOCIATED HISTORIC CONTEXTS The Sculpture of Dionicio Rodriguez in Texas C. FORM PREPARED BY Name/Title: Patsy Light, with Maria Pfeiffer (with assistance from Gregory W. Smith, Texas Historical Commission) Address: 300 Argyle Telephone: (210) 824-5914 City/Town: San Antonio, Texas State: Texas Zip Code: 78209 D. CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 6j>3n7J the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. (__ See contj^tjation sheet for additional comments.) Signature and title of certifying o'KLdal (SHPO, Texas Historical Commission) Date I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Hispanic/Latino American Older Adults

Ethno MEd Health and Health Care of Hispanic/Latino American Older Adults http://geriatrics.stanford.edu/ethnomed/latino Course Director and Editor in Chief: VJ Periyakoil, Md Stanford University School of Medicine [email protected] 650-493-5000 x66209 http://geriatrics.stanford.edu Authors: Melissa talamantes, MS University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio Sandra Sanchez-Reilly, Md, AGSF GRECC South Texas Veterans Health Care System; University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio eCampus Geriatrics IN THE DIVISION OF GENERAL INTERNAL MEDICINE http://geriatrics.stanford.edu © 2010 eCampus Geriatrics eCampus Geriatrics hispanic/latino american older adults | pg 2 CONTENTS Description 3 Culturally Appropriate Geriatric Care: Learning Resources: Learning Objectives 4 Fund of Knowledge 28 Instructional Strategies 49 Topics— Topics— Introduction & Overview 5 Historical Background, Assignments 49 Topics— Mexican American 28 Case Studies— Terminology, Puerto Rican, Communication U.S. Census Definitions 5 Cuban American, & Language, Geographic Distribution 6 Cultural Traditions, Case of Mr. M 50 Population Size and Trends 7 Beliefs & Values 29 Depression, Gender, Marital Status & Acculturation 31 Case of Mrs. R 51 Living Arrangements 11 Culturally Appropriate Geriatric Care: Espiritismo, Language, Literacy Case of Mrs. J 52 & Education 13 Assessment 32 Topics— Ethical Issues, Employment, End-of-Life Communication 33 Case of Mr. B 53 Income & Retirement 16 Background Information, Hospice, Eliciting Patients’ Perception -

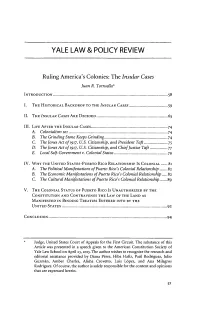

Ruling America's Colonies: the Insular Cases Juan R

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Ruling America's Colonies: The Insular Cases Juan R. Torruella* INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 58 I. THE HISTORICAL BACKDROP TO THE INSULAR CASES..................................-59 11. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ......................................... 65 III. LIFE AFTER THE INSULAR CASES.......................... .................. 74 A. Colonialism 1o ......................................................... 74 B. The Grinding Stone Keeps Grinding........... ....... ......................... 74 C. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and President Taft ................. 75 D. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and ChiefJustice Taft ............ 77 E. Local Self-Government v. Colonial Status...........................79 IV. WHY THE UNITED STATES-PUERTO Rico RELATIONSHIP IS COLONIAL...... 81 A. The PoliticalManifestations of Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......82 B. The Economic Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's ColonialRelationship.....82 C. The Cultural Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......89 V. THE COLONIAL STATUS OF PUERTO Rico Is UNAUTHORIZED BY THE CONSTITUTION AND CONTRAVENES THE LAW OF THE LAND AS MANIFESTED IN BINDING TREATIES ENTERED INTO BY THE UNITED STATES ............................................................. 92 CONCLUSION .................................................................... 94 * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. The substance of this Article was presented in