Mother India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

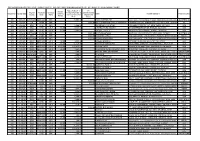

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Page10.Qxd (Page 1)

TUESDAY, AUGUST 8, 2017 (PAGE 12) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU JK State Cricket Academy T-20 C’ship 2 silver, 6 bronze Kerala HC lifts life ban on cricketer Sreesanth Mehraj’s hat-trick takes Valley Hunks medals for India at KOCHI, Aug 7: "Complacency in the matter on result, the writ petition is allowed. Asian Junior boxing the part of Sreesanth is really con- The life ban and other punishment into Ganderbal district finals In a relief to cricketer S demnable. To uphold the dignity of imposed on Sreesanth pursuant to NEW DELHI, Aug 7: Sreesanth, the Kerala High Court the game, he should have publicly the disciplinary proceedings against Excelsior Sports Correspondent the process. Mohammad Yaqoob today lifted the life ban imposed on disapproved (of) the conduct of Jiju Sreesanth stand quashed and are set of NCC Narbal was declared Man Gold eluded India as him by the BCCI in the wake of the Janardanan, especially when his aside...," he said. SRINAGAR, Aug 7: Seven of the Match for his solid 44. Satender Rawat (80+kg) and 2013 IPL spot-fixing scandal, saying name was dragged into the contro- The court had earlier sought the matches were played Monday The semi-final tie between Mohit Khatana (80kg) settled there was no incriminating evidence versy. BCCI's stand on the plea by the in State Cricket Academy T-20 Valley Hunks and SafaPora for silver medals after losing to pinpoint his involvement in match "Any how, having suffered a ban cricketer challenging the life ban Championship played across var- Blues in Ganderbal district was their final bouts in the Asian fixing. -

MAEL-203.Pdf

CONTENTS BLOCK 1 Selections from Ancient Texts Page No. Unit 1 Rigveda: Purusha Sukta 1-13 Unit 2 Isha Upanishad 14-30 Unit 3 The Mahabharata: The Yaksha-Yudhishthira Dialogue I 31-45 Unit 4 The Mahabharata: The Yaksha-Yudhishthira Dialogue II 46-76 BLOCK 2 Poetry in Translation Unit 5 Selections from Songs of Kabir 96-109 Unit 6 Selections from Ghalib 110-119 Unit 7 Rabindranath Tagore: Songs from Gitanjali 120-131 BLOCK 3 Poetry in English Unit 8 Sri Aurobindo and his Savitri 132-147 Unit 9 Savitri , Book Four: The Book of Birth and Quest 148-161 Unit 10 Nissim Ezekiel: “Philosophy”, “Enterprise” 162-173 Unit 11 Kamla Das: “Freaks”, “A Hot Noon in Malabar” 167-178 BLOCK 4 Fiction Unit 12 Somdev: Selections from Kathasaritsagar 174-184 Unit 13 Raja Rao: Kanthapura –I 185-191 Unit 14 Raja Rao: Kanthapura –II 192-200 BLOCK 5 Drama Unit 15 Kalidasa: Abhijnanashakuntalam –I 201-207 Unit 16 Kalidasa: Abhijnanashakuntalam –II 208-231 Unit 17 Vijay Tendulkar: Ghasiram Kotwal –I 232-240 Unit 18 Vijay Tendulkar: Ghasiram Kotwal –II 241-257 Indian Writing in English and in English Translation MAEL-203 UNIT ONE RIGVEDA: PURUSHA-SUKTA 1.1. Introduction 1.2. Objectives 1.3. A Background to Purusha-Sukta 1.4. Analysing the Text 1.4.1. The Purusha 1.4.2. Verse by verse commentary 1.4.3. The Yajna 1.5. Summing Up 1.6. Answers to Self Assessment Questions 1.7. References 1.8. Terminal and Model Questions Uttarakhand Open University 1 Indian Writing in English and in English Translation MAEL-203 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Block: Block One explores the foundations of Indian Literature. -

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

SUNDAY, JUNE 28, 2020 (PAGE 4) SPORTS A Dream Indian Cricket Team Sunil Fernandes The advent of limited-over cricket from the 1970s has irrevocably changed the way the game is played. With all fixtures locked down, one cricket fan lets his mind wander to what might have been. Vasant Raji, India’s oldest first-class cricketer, passed away recently. He was 100 years old. His passing, perhaps, is a time for cricket to remember and cele- brate some of the other great stalwarts of Indian test cricket too – especially when the coronavirus pandemic has meant no sporting events can take place. India played its ever first ever test match at the historic Lords Cricket Ground in 1932 against England. Forty-two years later, in 1974, India played its first ever limited-over international, also in England. Pahlan Ratanji “Polly” Unarguably, the advent of limited-over cricket, from the 1970s, has irrevoca- Mulvantrai Himmatlal Vijay Merchant Lala Amarnath C.K. “Colonel” Nayudu M.A.K. “Tiger” Pataudi bly changed the way the game is played. We have come across several compila- “Vinoo” Mankad Bharadwaj (Captain) Umrigar (Vice-Captain) tions of All Time Best India XI but hardly any All Time Indian XI consisting of those cricketers, whose cricket wasn’t affected or influenced by the one-day game at all, those who played test matches only. The legends of a forgotten era. Here is that XI. THE OPENERS Mulvantrai Himmatlal “Vinoo” Mankad Along with Pankaj Roy, this right-hand batsman scored 413 runs, the then highest ever partnership by an opening pair. -

Mother India

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE Vol. LX No. 6 “Great is Truth and it shall prevail” CONTENTS Sri Aurobindo SELF (Poem) ... 421 THE SCIENCE OF CONSCIOUSNESS ... 422 The Mother ‘NO ERROR CAN PERSIST IN FRONT OF THEE’ ... 426 THE POWER OF WORDS ... 427 Amal Kiran (K. D. Sethna) “SAKUNTALA” AND “SAKUNTALA’S FAREWELL”—CORRESPONDENCE WITH SRI AUROBINDO ... 429 Priti Das Gupta MOMENTS, ETERNAL ... 435 Arun Vaidya AN ETERNAL DREAM ... 440 Prabhjot Kulkarni WHO AM I (Poem) ... 447 S. V. Bhatt PAINTING AS SADHANA: KRISHNALAL BHATT (1905-1990) ... 448 Narad (Richard Eggenberger) TEHMI-BEN—NARAD REMEMBERS ... 456 Sitangshu Chakrabortty LORD AND MOTHER NATURE (Poem) ... 464 Bibha Biswas THE BIRTH OF “BATIK WORK” ... 465 Prithwindra Mukherjee BANKIMCHANDRA CHATTERJEE ... 468 Chunilal Chowdhury A WORLD WITHOUT WAR ... 476 Prema Nandakumar DEVOTIONAL POETRY IN TAMIL ... 480 Pujalal NAVANIT STORIES ... 490 421 SELF He said, “I am egoless, spiritual, free,” Then swore because his dinner was not ready. I asked him why. He said, “It is not me, But the belly’s hungry god who gets unsteady.” I asked him why. He said, “It is his play. I am unmoved within, desireless, pure. I care not what may happen day by day.” I questioned him, “Are you so very sure?” He answered, “I can understand your doubt. But to be free is all. It does not matter How you may kick and howl and rage and shout, Making a row over your daily platter. “To be aware of self is liberty. Self I have got and, having self, am free.” SRI AUROBINDO (Collected Poems, SABCL, Vol. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

Foreign Contribution Report

SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM TRUST PONDICHERRY FOREIGN CONTRIBUTION DONORS LIST OCTOBER-20 TO DECEMBER-20(Q3) Rupee Value of ( FC Foreign Original Payment Currency Foreign Chqs/ DDs & Donation(Cash) Receipt No F Receipt Date Currency Name Present Address-1 Present Country Country mode Name Currency Notes )1st (Rupees) 1st Amount Recp. Recpt 300 1-10-20 AUSTRALIA NEFT HDFC INR 5,308.00 RAJIV RATTAN DR GRATITUDE, 159 BOUNDARY ROAD, WAHROONGA, NSW-2076 AUSTRALIA 301 2-10-20 UK CASH INR 1,000.00 SRI AUROBINDO CIRCLE(ASHRAM) 8 SHERWOOD AVE., STREATHAM VALE, SW16 5EW, LONDON UK 302 2-10-20 USA CHQ INR 6,000.00 AURINDAK K GHATAK 455 MAIN STREET # 16F, NEW YORK, NY-10044 USA 303 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 100.00 7,231.00 CHITRALEKHA GHOSH 22 INDEPENDENCE DR, EDISON, NJ-08820 USA 304 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 101.00 7,303.00 SATISH J PATEL 1413 BRYS DR, GROSSE POINTE, MI-48236 USA 305 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,001.00 R VISWANATHAN UNIT-330, 298 SUSSEX ST, NSW-2000, SYDNEY AUSTRALIA 306 2-10-20 USA CASH INR 1,000.00 RICHARD HARTZ C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 307 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,000.00 SUSAN CROTHERS C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 308 2-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 50.00 3,685.25 DINESH MANDAL 1013 ROYAL STOCK LN, CARY, NC-27513 USA 309 2-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 205.00 15,127.46 VIJAYA CHINNADURAI 1739 STIFEL LANE DR, CHESTERFIELD, MO-63017 USA 310 3-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 5,000.00 3,65,425.00 KUSUM PATEL 1694 HIDDEN OAK TRAIL,MANSFIELD, OH-44906 USA 311 3-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 20.00 1,461.70 RAMAKRISHNAN -

Essays in Philosophy and Yoga

13 Essays in Philosophy and Yoga VOLUME 13 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1998 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Essays in Philosophy and Yoga Shorter Works 1910 – 1950 Publisher's Note Essays in Philosophy and Yoga consists of short works in prose written by Sri Aurobindo between 1909 and 1950 and published during his lifetime. All but a few of them are concerned with aspects of spiritual philosophy, yoga, and related subjects. Short writings on the Veda, the Upanishads, Indian culture, politi- cal theory, education, and poetics have been placed in other volumes. The title of the volume has been provided by the editors. It is adapted from the title of a proposed collection, ªEssays in Yogaº, found in two of Sri Aurobindo's notebooks. Since 1971 most of the contents of the volume have appeared under the editorial title The Supramental Manifestation and Other Writings. The contents are arranged in ®ve chronological parts. Part One consists of essays published in the Karmayogin in 1909 and 1910, Part Two of a long essay written around 1912 and pub- lished in 1921, Part Three of essays and other pieces published in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1921, Part Four of an essay published in the Standard Bearer in 1920, and Part Five of a series of essays published in the Bulletin of Physical Education in 1949 and 1950. Many of the essays in Part Three were revised slightly by the author and published in small books between 1920 and 1941. -

October 2016 Dossier

INDIA AND SOUTH ASIA: OCTOBER 2016 DOSSIER The October 2016 Dossier highlights a range of domestic and foreign policy developments in India as well as in the wider region. These include analyses of the ongoing confrontation between India and Pakistan, the measures by the government against black money and terrorism as well as the scenarios in India's mega-state Uttar Pradesh on the eve of crucial state elections in 2017, the 17th India-Russia Annual Summit and the Eighth BRICS Summit. Dr Klaus Julian Voll FEPS Advisor on Asia With Dr. Joyce Lobo FEPS STUDIES OCTOBER 2016 Part I India - Domestic developments • Confrontation between India and Pakistan • Modi: Struggle against black money + terrorism • Uttar Pradesh: On the eve of crucial elections • Pollution: Delhi is a veritable gas-chamber Part II India - Foreign Policy Developments • 17th India-Russia Annual Summit • Eighth BRICS Summit Part III South Asia • Outreach Summit of BRICS Leaders with the Leaders of BIMSTEC 2 Part I India - Domestic developments Dr. Klaus Voll analyses the confrontation between India and Pakistan, the measures by the government against black money and terrorism as well as the scenarios in India's mega-state Uttar Pradesh on the eve of crucial state elections in 2017 and the extreme pollution crisis in Delhi, the National Capital ReGion and northern India. Modi: Struggle against black money + terrorism: 500 and 1000-Rupee notes invalidated Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed on the 8th of November 2016 the nation in Hindi and EnGlish. Before he had spoken to President Pranab Mukherjee and the chiefs of the army, navy and air force. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

A New Creation on Earth: Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mother Mirra Alfassa

A New Creation on Earth: Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mother Mirra Alfassa Stephen Lerner Julich1 Abstract: This paper acts as a précis of the author’s dissertation in East-West Psychology at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. The dissertation, entitled Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mirra Alfassa (1878- 1973), Mother of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram: A Jungian Hermeneutic, is a cross-cultural exploration and analysis of symbols of death and transformation found in Mother’s conversations and writings, undertaken as a Jungian amplification. Focused mainly on her discussions of the psychic being and death, it is argued that the Mother remained rooted in her original Western Occult training, and can best be understood if this training, under the guidance of Western Kabbalist and Hermeticist Max Théon, is seen, not as of merely passing interest, but as integral to her development. Keywords: C.G. Jung, death, integral yoga, Mother Mirra Alfassa, psychic being, Sri Aurobindo, transformation. Mirra Alfassa was one of those rare individuals who was in life a living symbol, at once human, and identical to the indescribable higher reality. Her yoga was to tear down the barrier that separates heaven and earth by defeating the Lord of Death, through breaking the habituated belief that exists in every cell of the body that all life must end in death and dissolution. Ultimately, her goal was to transform and spiritualize matter. In my dissertation I applied a Jungian lens to amplify the Mother’s statements. Amplification, as it is usually understood in Jungian circles, is a method used to expand an analyst’s grasp of images and symbols that appear in the dreams of analysands. -

Dharma in the Mahabharata As a Response to Ecological Crises: a Speculation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Trumpeter - Journal of Ecosophy (Athabasca University) Dharma in the Mahabharata as a response to Ecological Crises: A speculation By Kamesh Aiyer Abstract Without doing violence to Vyaasa, the Mahabharata (Vyaasa, The Mahabharata 1933-1966) can be properly viewed through an ecological prism, as a story of how “Dharma” came to be established as a result of a conflict over social policies in response to on-going environmental/ecological crises. In this version, the first to recognize the crises and to attempt to address them was Santanu, King of Hastinapur (a town established on the banks of the Ganges). His initial proposals evoked much opposition because draconian and oppressive, and were rescinded after his death. Subsequently, one of Santanu’s grandsons, Pandu, and his children, the Pandavas, agreed with Santanu that the crises had to be addressed and proposed more acceptable social policies and practices. Santanu’s other grandson, Dhritarashtra, and his children, the Kauravas, disagreed, believing that nothing needed to be done and opposed the proposed policies. The fight to establish these policies culminated in the extended and widespread “Great War” (the “Mahaa-Bhaarata”) that was won by the Pandavas. Some of the proposed practices/social policies became core elements of "Hinduism" (such as cow protection and caste), while others became accepted elements of the cultural landscape (acceptance of the rights of tribes to forests as “commons”). Still other proposals may have been implied but never became widespread (polyandry) or may have been deemed unacceptable and immoral (infanticide).