Discourse in Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Lost Arab Hollywood: Female Representation in Pre-Revolutionary Contemporary Egyptian Cinema

A LOST ARAB HOLLYWOOD: FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN PRE-REVOLUTIONARY CONTEMPORARY EGYPTIAN CINEMA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Walsh School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service By Yasmine Salam Washington, D.C. April 20, 2020 2 Foreword This project is dedicated to Mona, Mehry and Soha. Three Egyptian women whose stories will follow me wherever I go. As a child, I never watched Arabic films. Growing up in London to an Egyptian family meant I desperately craved to learn pop-culture references that were foreign to my ancestors. It didn’t feel ‘in’ to be different and as a teenager I struggled to reconcile two seemingly incompatible facets of my identity. Like many of the film characters in this study, I felt stuck at a crossroads between embracing modernity and respecting tradition. I unknowingly opted to be a non-critical consumer of European and American mass media at the expense of learning from the rich narratives emanating from my own region. My British secondary school’s curriculum was heavily Eurocentric and rarely explored the history of my people further than as tertiary figures of the past. That is not to say I rejected my cultural heritage upfront. Women in my family went to great lengths to share our intricate family history and values. My childhood was as much shaped by dinner-table conversations at my Nona’s apartment in Cairo and long summers at the Egyptian coast, as it was by my life in Europe. -

Faten Hamama and the 'Egyptian Difference' in Film Madamasr.Com January 20

Faten Hamama and the 'Egyptian difference' in film madamasr.com January 20 In 1963, Faten Hamama made her one and only Hollywood film. Entitled Cairo, the movie was a remake of The Asphalt Jungle, but refashioned in an Egyptian setting. In retrospect, there is little remarkable about the film but for Hamama’s appearance alongside stars such as George Sanders and Richard Johnson. Indeed, copies are extremely difficult to track down: Among the only ways to watch the movie is to catch one of the rare screenings scheduled by cable and satellite network Turner Classic Movies. However, Hamama’s foray into Hollywood is interesting by comparison with the films she was making in “the Hollywood on the Nile” at the time. The next year, one of the great classics of Hamama’s career, Al-Bab al-Maftuh (The Open Door), Henri Barakat’s adaptation of Latifa al-Zayyat’s novel, hit Egyptian screens. In stark contrast to Cairo, in which she played a relatively minor role, Hamama occupied the top of the bill for The Open Door, as was the case with practically all the films she was making by that time. One could hardly expect an Egyptian actress of the 1960s to catapult to Hollywood stardom in her first appearance before an English-speaking audience, although her husband Omar Sharif’s example no doubt weighed upon her. Rather, what I find interesting in setting 1963’s Cairo alongside 1964’s The Open Door is the way in which the Hollywood film marginalizes the principal woman among the film’s characters, while the Egyptian film sets that character well above all male counterparts. -

FILMS on Palestine-Israel By

PALESTINE-ISRAEL FILMS ON THE HISTORY of the PALESTINE-ISRAEL CONFLICT compiled with brief introduction and commentary by Rosalyn Baxandall A publication of the Palestine-Israel Working Group of Historians Against the War (HAW) December 2014 www.historiansagainstwar.org Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial – ShareAlike 1 Introduction This compilation of films that relate to the Palestinian-Israeli struggle was made in July 2014. The films are many and the project is ongoing. Why film? Film is often an extraordinarily effective tool. I found that many students in my classes seemed more visually literate than print literate. Whenever I showed a film, they would remember the minute details, characters names and sub-plots. Films were accessible and immediate. Almost the whole class would participate and debates about the film’s meaning were lively. Film showings also improved attendance at teach-ins. At the Truro, Massachusetts, Library in July 2014, the film Voices Across the Divide was shown to the biggest audiences the library has ever had, even though the Wellfleet Library and several churches had refused to allow the film to be shown. Organizing is also important. When a film is controversial, as many in this pamphlet are, a thorough organizing effort including media coverage will augment the turnout for the film. Many Jewish and Palestinian groups list films in their resources. This pamphlet lists them alphabetically, and then by number under themes and categories; the main listings include summaries, to make the films more accessible and easier to use by activist and academic groups. 2 1. 5 Broken Cameras, 2012. -

154 Features Features 155

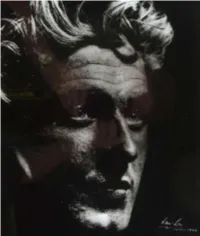

154 Features Features 155 Van Leo from Turkey to Egypt By Martina Corgnati 156 Features The first photographic forays in the Middle East occurred within the Armenian community. In Egypt, legendary figures such as G. Lekegian, who arrived from Istanbul around 1880, kick-started an Armenian led monopoly over photography and the photographic business. Gradually, other photogra- phers began to populate the area around Lekegian’s Cairo studio, located near Opera Square, creating a small “special- ized” neighborhood in both the commercial and ethnic sense. Favored, perhaps, by historical familiarity with images and Christian religion’s acceptance of representational media; Armenians tended to pass on the trade, which at the time could only be learned through experience in the workshops. Due to this process, Armenian photographers were often quite experimental. Armand (Armenak Arzrouni, b. Erzurum 1901 – d. Cairo 1963), Archak, Tartan and Alban (the art name of Aram Arnavoudian, b. Istanbul 1883 – d. Cairo 1961), for example, who arrived in Cairo in the early twentieth century, were some of the first to try “creative” photographic tech- niques that played with variations in composition and points of view. The first photographer Van Leo met in Cairo was an Arme- nian artist called Varjabedian. Still a child, Van Leo regularly visited his provincial photography studio and, years later, Varjabedian would be the one to introduce him to the photog- raphy “temple” in Cairo. This was the name given to the area from Opera Square to Qasr al Nil Street where an abundance of photographic studios and foreign jewelers mingled with Leon (Leovan) Boyadjian, known in the art world as the Egyptian artistic aura. -

Arabic Films

Arabic Films Call # HQ1170 .A12 2007 DVD Catalog record http://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b6528747~S7 TITLE 3 times divorced / a film by Ibtisam Sahl Mara'ana a Women Make Movies release First Hand Films produced for The Second Authority for Television & Radio the New Israeli Foundation for Cinema & Film Gon Productions Ltd Synopsis Khitam, a Gaza-born Palestinian woman, was married off in an arranged match to an Israeli Palestinian, followed him to Israel and bore him six children. When her husband divorced her in absentia in the Sharia Muslim court and gained custody of the children, Khitam was left with nothing. She cannot contact her children, has no property and no citizenship. Although married to an Israeli, a draconian law passed in 2002 barring any Palestinian from gaining Israeli citizenship has made her an illegal resident there. Now she is out on a dual battle, the most crucial of her life: against the court which always rules in favor of the husband, and against the state in a last-ditch effort to gain citizenship and reunite with her children Format DVD format Call # DS119.76 .A18 2008 DVD Catalog record http://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b6514808~S7 TITLE 9 star hotel / Eden Productions Synopsis A look at some of the many Palestinians who illegally cross the border into Israel, and how they share their food, belongings, and stories, as well as a fear of the soldiers and police Format DVD format Call # PN1997 .A127 2000z DVD Catalog record http://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b6482369~S7 TITLE 24 sāʻat ḥubb = 24 hours of love / Aflām al-Miṣrī tuqaddimu qiṣṣah wa-sīnāryū wa-ḥiwār, Fārūq Saʻīd افﻻم المرصي تقدم ؛ قصة وسيناريوا وحوار, فاروق سعيد ؛ / hours of love ساعة حب = ikhrāj, Aḥmad Fuʼād; 24 24 اخراج, احمد فؤاد Synopsis In this comedy three navy officers on a 24 hour pass go home to their wives, but since their wives doubt their loyalty instead of being welcomed they are ignored. -

Semester at Sea Course Syllabus

SEMESTER AT SEA COURSE SYLLABUS Voyage: Summer 2013 Discipline: Media Studies MDST 2502: Mediterranean Cinemas after 1945 Division: Lower division Faculty Name: Ernesto R. Acevedo-Muñoz, Ph.D. COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course presents students with a history and overview of the major European film movements, the most influential films and directors, and the relationship between European cinemas, history, and culture from 1945 to the 2000s. Focusing largely –though not exclusively- on the principal film industries of France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Turkey and Northern Africa, the course draws direct comparisons and relationships between the practices of cinema, and developments in history and society. COURSE OBJECTIVES: Students will explore the styles and significance of such influential movements as Italian Neorealism (1944-1952), the French the New Wave (1958-1964), the “Golden Age” of Greek cinema (1950s-1960s) and Spanish cinema before and after democratization. The course will consider specific relationships of national cinemas in general, and exemplary films in particular, to representations of landscape, the city, and key historical junctures. Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, Italy 1945). REQUIRED TEXTBOOK: Elizabeth Ezra (ed.) European Cinema. Oxford U. Press, 2004. Other reading materials will be available electronically. Our most important texts, of course, are the movies assigned for each class meeting. Course Schedule C1- June 19: Introductions and rules of the game. Opening lecture/discussion: “Understanding cultures through film.” Reading: Ezra, Introduction: “A brief history of cinema in Europe.” C2- June 20: The Hollywood Standard. Casablanca and Classical Cinema. Film: Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, US 1942). C3- June 21: War as a starting point. Film: Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, Italy 1945). -

Westminsterresearch Power, Arab Media Moguldum & Gender Rights

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Power, Arab media Moguldum & gender rights as entertainment in the Middle East El Mkaouar, L. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Dr Loubna El Mkaouar, 2016. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] POWER, ARAB MEDIA MOGULDUM & GENDER RIGHTS AS ENTERTAINMENT IN THE MDDLE EAST Loubna El Mkaouar A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster, For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Communication and Media Research Institute University of Westminster April 2016 1 Abstract Discourse is a giant field of research and gender related rights are still a disputed area of thinking. Thus, when Arab transnational satellite televisions produce dialogues, images, stories and narratives about the disputed “universal” gender rights in the Middle East, the big questions remain how and why. According to De Beauvoir (1949), one becomes woman and to Butler (1990) one is not born a gender at all but is “done” and “undone” to become one via discourse. Islamic feminism speaks of a cultural/religious specificity in defending women rights and even gender diversity based on new Quranic interpretations. -

Faten Hamama and Hind Rustom: Stars from Different Heavens

24 al-raida Issue 122 - 123 | Summer / Fall 2008 Faten Hamama and Hind Rustom: Stars from Different Heavens Jean Said Makdissi One of the current topics in critical discussions on the Arab cinema is the gendered nature of nationalist and national themes. It has been repeatedly said that in the Egyptian cinema, Egypt itself is often represented by an idealized woman. Both Viola Shafik (1998) and Lina Khatib (2006) make much of this idea, and investigate it with reference to particular films. In this context the idealizing title sayidat al-shasha al-arabiyya, (i.e. the lady of the Arab screen) has been universally granted to Faten Hamama, the grande dame of the Egyptian cinema and one of the most prolific of its actresses, and thus she is the ideal embodiment on the screen not only of Egyptian and Arab womanhood, but also of Egypt’s view of itself and of the Arab world. To study the output of Faten Hamama is to have an idea of how Egyptians – and perhaps all Arabs – like to see themselves, and especially their women. But to arrive at a clearer idea of the self-definition of the Arab world and its fantasy of the feminine ideal I believe it would be helpful to contrast her work with that of Hind Rustom, who both in her physical appearance and the persona she represents on screen is almost directly antithetical to Faten. In preparation for this article I have seen more than two dozen films, and of course drawn on decades of experience with the Egyptian cinema. -

Network Films: a Global Genre?

Network Films: a Global Genre? Vivien Claire Silvey December 2012 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. ii This thesis is solely my original work, except where due reference is given. iii Acknowledgements I am extremely grateful for all the time and effort my dear supervisor Cathie Summerhayes has invested throughout this project. Her constant support, encouragement, advice and wisdom have been absolutely indispensable. To that master of words, puns and keeping his hat on during the toughest times of semester, Roger Hillman, I extend profound gratitude. Roger‟s generosity with opportunities for co-publishing, lecturing and tutoring, and enthusiasm for all things Turkish German, musical and filmic has been invaluable. For all our conversations and film-loans, I warmly say to Gino Moliterno grazie mille! I am indebted to Gaik Cheng Khoo, Russell Smith and Fiona Jenkins, who have provided valuable information, lecturing and tutoring roles. I am also grateful for the APA scholarship and for all the helpful administration staff in the School of Cultural Inquiry. At the heart of this thesis lies the influence of my mother Elizabeth, who has taken me to see scores of “foreign” and “art” films over the years, and my father Jerry, with whom I have watched countless Hollywood movies. Thank you for instilling in me a fascination for all things “world cinema”, for your help, and for providing a caring home. To my gorgeous Dave, thank you for all your love, motivation, cooking and advice. I am enormously honoured to have you by my side. -

David Lean: DR. ZHIVAGO (1965, 197 Min.)

March 12, 2019 (XXXVIII:7) David Lean: DR. ZHIVAGO (1965, 197 min.) DIRECTOR David Lean WRITING Robert Bolt screenplay adapted from the Boris Pasternak novel PRODUCER Carlo Ponti MUSIC Maurice Jarre CINEMATOGRAPHY Freddie Young EDITING Norman Savage PRODUCTION DESIGN John Box ART DIRECTION Terence Marsh SET DECORATION Dario Simoni COSTUME DESIGN Phyllis Dalton The film permeated the 1966 Academy Awards, winning Oscars for Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium (Robert Bolt), Best Cinematography, Color (Freddie Young), Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, Color (John Box, Terence Marsh, and Dario Simoni), Best Costume Design, Color (Phyllis Dalton), and Best Music, Score (Maurice Jarre). The Mark Eden...Engineer at Dam film also received Oscar nominations for Best Picture (Carlo Erik Chitty...Old Soldier Ponti), Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Tom Courtenay), Best Roger Maxwell...Beef-Faced Colonel Director (David Lean), Best Sound (A.W. Watkins, Franklin Wolf Frees...Delegate Milton), and Best Film Editing (Norman Savage). The film was Gwen Nelson...Female Janitor also nominated for the Cannes Palm d’Or. Lucy Westmore...Katya Lili Muráti...The Train Jumper (as Lili Murati) CAST Peter Madden...Political Officer Omar Sharif...Yuri Julie Christie...Lara DAVID LEAN (b. March 25, 1908 in Croydon, Surrey, England, Geraldine Chaplin...Tonya UK—d. April 16, 1991 (age 83) in London, England, UK) was Rod Steiger...Komarovsky an English film director (19 credits), producer, screenwriter (10 Alec Guinness...Yevgraf credits) -

Catalogue of the African Studies Library Film Collection in UCT Libraries Special Collections

Catalogue of the African Studies Library Film Collection in UCT Libraries Special Collections Any queries regarding the ASL film collection please contact Bev Angus ([email protected]) Updated:June 2015 Introduction In film, as with all other African Studies material in Special Collections, we collect comprehensively on South and Southern Africa and we are also committed to strengthening and broadening our film coverage of the rest of Africa to meet existing needs and to create new opportunities for research. Film is a powerful and accessible medium for conveying the stories and images of Africa, past and present. The African continent has a long and proud tradition of film-making, and has produced many film-makers of international renown. Our collection contains documentaries, television series and feature films made by both African and international film-makers. Besides supporting the teaching and research programmes of the University of Cape Town, the African Studies Library makes provision for the preservation of the films in the collection. Please note: The films in the ASL are primarily for viewing by members of the University of Cape Town community. For a collection of African films with public access see the Western Cape Provincial Library Service collection at http://cplweb.pals.gov.za Tips on searching the collection: To facilitate searching, click the binoculars in the toolbar. Select Use Advanced Search Options. If you know the title of the film, enter the exact title in the box and select Match Exact Word or Phrase in the dropdown box e.g. “Cry the Beloved Country” For a keyword search where the exact title is unknown or you are searching around a particular topic, enter appropriate keywords in the box provided, then select Match any of the Words in the drop-drown box below e.g. -

To View This Issue Please Click This Link

May - July 2008 page 1 www.bibalex.org/alexmed/ May - July 2008 page 2 Good Food Ends with Good Talk Alexandria’s Inaugural International Food Fair Edward Lewis the Mediterranean—is an ambitious attempt to exploit Alexandria’s rich and diverse cuisine, whilst highlighting the city’s multicultural character. It is hoped that by stressing the variety of cuisine in addition to the shared traditions of neighboring regions, the project will celebrate both diversity and collective traits of the Euro- Med. The International Food Fair, the first of three of the project’s deliverables, was held over two days and hailed a success, primarily due to the contribution and effort made by the different communities of Alexandria and the professional establishments involved. The first day saw a wide range of mezza, main courses, sweets and beverages displayed under a large white At first, food may seem an unlikely means by which tent set in the magnificent setting of the Villa Antoniadis, to encourage intercultural dialogue and exchange. itself a true example of Alexandrian cosmopolitanism It seems too simple, too ‘ordinary’ a subject with and diversity. A British subject who hailed from the which to tackle such a daunting task as uniting Greek island of Lemnos, Sir John Antoniadis was an countries and bringing people together within the Alexandrian and a generous patron of the city and its Euro Mediterranean Region. Yet the more one thinks Greek community. In the mid-nineteenth century, he about food, the more one realizes that it is in fact the developed a garden estate which was to become the perfect vehicle with which to do exactly that.