UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No. 7 (2021), 2845-2852 Research Article Undermining Colonial Space in Cinematic Discourse

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No. 7 (2021), 2845-2852 Research Article Undermining Colonial Space In Cinematic Discourse Dr. Ammar Ibrahim Mohammed Al-Yasri Television Arts specialization Ministry of Education / General Directorate of Holy Karbala Education [email protected] Article History: Received: 11 January 2021; Revised: 12 February 2021; Accepted: 27 March 2021; Published online: 16 April 2021 Abstract: There is no doubt that artistic races are the fertile factor in philosophy in all of its perceptions, so cinematic discourse witnessed from its early beginnings a relationship to philosophical thought in all of its proposals, and post-colonial philosophy used cinematic discourse as a weapon that undermined (colonial) discourse, for example cinema (Novo) ) And black cinema, Therefore, the title of the research came from the above introduction under the title (undermining the colonial space in cinematic discourse) and from it the researcher put the problem of his research tagged (What are the methods for undermining the colonial space in cinematic discourse?) And also the first chapter included the research goal and its importance and limitations, while the second chapter witnessed the theoretical framework It included two topics, the first was under the title (post-colonialism .. the conflict of the center and the margin) and the second was under the title (post-colonialism between cinematic types and aspects of the visual form) and the chapter concludes with a set of indicators, while the third chapter included research procedures, methodology, society, sample and analysis of samples, While the fourth chapter included the results and conclusions, and from the results obtained, the research sample witnessed the use of undermining the (colonial) act, which was embodied in the face of violence with violence and violence with culture, to end the research with the sources. -

Curriculum Vitae

Name: Taiseer Elias Date: 08/11/2015 CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Personal Details Permanent Home Address: P.O. Box 686, El-Fawar, 20200 Shefaram, Israel Home Telephone Number: (04) 986-2365 Office Telephone Number: (04) 828-8481 Cellular Phone: (050) 780-5055 Fax Number: (04) 986-2365 Electronic Address: [email protected] 2. Higher Education . A. Undergraduate and Graduate Studies Period of Name of Institution Degree Year of Approval of Study and Department Degree 1974–79 Rubin Conservatory graduated cum 1979 of Music - Haifa laude 1980–83 Jerusalem Academy performance and - of Music and Dance music education 1983–85 Hebrew University B.A. in 1985 of Jerusalem: musicology cum Musicology laude; Department minor in Arabic literature and language, and Theatre. 1986–91 Hebrew University M.A. in 1991 of Jerusalem: musicology cum Musicology laude Department 2001–07 Hebrew University Ph.D. in 2007 of Jerusalem: Musicology Musicology Department 1 B. Post-Doctoral Studies NONE 3. Academic Ranks and Tenure in Institutes of Higher Education Dates Name of Institution and Rank/Position Department 1982-1983 David Yellin Teachers Music Lecturer College, Jerusalem 1993 Oranim College, Tivon Music Lecturer 1993-1995 Arab Teachers Training Music Lecturer Institute - Beit Berl College, Kfar Saba 1996-Present Jerusalem Academy of Music Professor of Violin, and Dance: Eastern Music Oud, Singing and Department Theory - Adjunct Associate Professor (with tenure) 2001– 2011 Bar-Ilan University – Professor of Theory - Department of Music Adjunct Associate Professor -

When Maqam Is Reduced to a Place Eyal Sagui Bizawe

When Maqam is Reduced to a Place Eyal Sagui Bizawe In March 1932, a large-scale impressive festival took place at the National Academy of Music in Cairo: the first international Congress of Arab Music, convened by King Fuad I. The reason for holding it was the King’s love of music, and its aim was to present and record various musical traditions from North Africa and the Middle East, to study and research them. Musical delegations from Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Morocco, Algiers, Tunisia and Turkey entered the splendid building on Malika Nazli Street (today Ramses Street) in central Cairo and in between the many performances experts discussed various subjects, such as musical scales, the history of Arab music and its position in relation to Western music and, of course: the maqam (pl. maqamat), the Arab melodic mode. The congress would eventually be remembered, for good reason, as one of the constitutive events in the history of modern Arab music. The Arab world had been experiencing a cultural revival since the 19th century, brought about by reforms introduced under the Ottoman rule and through encounters with Western ideas and technologies. This renaissance, termed Al-Nahda or awakening, was expressed primarily in the renewal of the Arabic language and the incorporation of modern terminology. Newspapers were established—Al-Waq’i’a al-Masriya (Egyptian Affairs), founded under orders of Viceroy and Pasha Mohammad Ali in 1828, followed by Al-Ahram (The Pyramids), first published in 1875 and still in circulation today; theaters were founded and plays written in Arabic; neo-classical and new Arab poetry was written, which deviated from the strict rules of classical poetry; and new literary genres emerged, such as novels and short stories, uncommon in Arab literature until that time. -

1 GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY VISITING FILM SERIES April 29

GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY VISITING FILM SERIES April 29, 2020 I am pleased to be here to talk about my role as Deputy Director of the Washington, DC International Film Festival, more popularly known as Filmfest DC, and as Director of the Arabian Sights Film Festival. I would like to start with a couple of statistics: We all know that Hollywood films dominate the world’s movie theaters, but there are thousands of other movies made around the globe that most of us are totally unaware of or marginally familiar with. India is the largest film producing nation in the world, whose films we label “Bollywood”. India produces around 1,500 to 2,000 films every year in more than 20 languages. Their primary audience is the poor who want to escape into this imaginary world of pretty people, music and dancing. Amitabh Bachchan is widely regarded as the most famous actor in the world, and one of the greatest and most influential actors in world cinema as well as Indian cinema. He has starred in at least 190 movies. He is a producer, television host, and former politician. He is also the host of India’s Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. Nigeria is the next largest film producing country and is also known as “Nollywood”, producing almost 1000 films per year. That’s almost 20 films per week. The average Nollywood movie is produced in a span of 7-10 days on a budget of less than $20,000. Next comes Hollywood. Last year, 786 films were released in U.S. -

Asmahan Presence and Distinctive Performance Style

A versatile singer renowned for her powerful voice, enchanting stage Asmahan presence and distinctive performance style. Amal Al-Atrash, (1912-1944), better known by her stage name Asmahan, was an exceptional Syrian-Egyptian singer and actor who rose to fame in Egypt in the 1930s and early 1940s. Born into a prominent family, she moved from Syria to Egypt with her mother and siblings due to political unrest. To earn a living, her mother, who had an excellent voice, began singing and playing the oud. She was a source of inspiration for Asmahan and her brother, Farid Al-Atrash, who also became a famous musician. Asmahan, like her mother, demonstrated vocal talent from an early age, and went on to sing songs written by DID YOU KNOW? renowned musicians in some of Egypt’s most important venues. Asmahan collaborated with the great artist Mohammed Abdel Wahab, Asmahan was a versatile singer celebrated singing one of his compositions for for her powerful voice, enchanting stage the Film Yawm Sa’id (Happy Day). presence and distinctive performance style. She was not only skilled in tarab, but she was also incredibly innovative. Her voice was FUN FACT regarded as one of the few in the Arab world at the time able to compete with renowned Asmahan and her brother Farid Al- Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum. Atrash starred in the successful 1941 film Intisar al-Shabab (The Triumph Despite her short life, Asmahan performed of Youth), in which they portray two and recorded several memorable songs young singers looking for fame in Egypt. composed by renowned musicians, including her brother Farid Al-Atrash. -

A Lost Arab Hollywood: Female Representation in Pre-Revolutionary Contemporary Egyptian Cinema

A LOST ARAB HOLLYWOOD: FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN PRE-REVOLUTIONARY CONTEMPORARY EGYPTIAN CINEMA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Walsh School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service By Yasmine Salam Washington, D.C. April 20, 2020 2 Foreword This project is dedicated to Mona, Mehry and Soha. Three Egyptian women whose stories will follow me wherever I go. As a child, I never watched Arabic films. Growing up in London to an Egyptian family meant I desperately craved to learn pop-culture references that were foreign to my ancestors. It didn’t feel ‘in’ to be different and as a teenager I struggled to reconcile two seemingly incompatible facets of my identity. Like many of the film characters in this study, I felt stuck at a crossroads between embracing modernity and respecting tradition. I unknowingly opted to be a non-critical consumer of European and American mass media at the expense of learning from the rich narratives emanating from my own region. My British secondary school’s curriculum was heavily Eurocentric and rarely explored the history of my people further than as tertiary figures of the past. That is not to say I rejected my cultural heritage upfront. Women in my family went to great lengths to share our intricate family history and values. My childhood was as much shaped by dinner-table conversations at my Nona’s apartment in Cairo and long summers at the Egyptian coast, as it was by my life in Europe. -

Faten Hamama and the 'Egyptian Difference' in Film Madamasr.Com January 20

Faten Hamama and the 'Egyptian difference' in film madamasr.com January 20 In 1963, Faten Hamama made her one and only Hollywood film. Entitled Cairo, the movie was a remake of The Asphalt Jungle, but refashioned in an Egyptian setting. In retrospect, there is little remarkable about the film but for Hamama’s appearance alongside stars such as George Sanders and Richard Johnson. Indeed, copies are extremely difficult to track down: Among the only ways to watch the movie is to catch one of the rare screenings scheduled by cable and satellite network Turner Classic Movies. However, Hamama’s foray into Hollywood is interesting by comparison with the films she was making in “the Hollywood on the Nile” at the time. The next year, one of the great classics of Hamama’s career, Al-Bab al-Maftuh (The Open Door), Henri Barakat’s adaptation of Latifa al-Zayyat’s novel, hit Egyptian screens. In stark contrast to Cairo, in which she played a relatively minor role, Hamama occupied the top of the bill for The Open Door, as was the case with practically all the films she was making by that time. One could hardly expect an Egyptian actress of the 1960s to catapult to Hollywood stardom in her first appearance before an English-speaking audience, although her husband Omar Sharif’s example no doubt weighed upon her. Rather, what I find interesting in setting 1963’s Cairo alongside 1964’s The Open Door is the way in which the Hollywood film marginalizes the principal woman among the film’s characters, while the Egyptian film sets that character well above all male counterparts. -

Arabic Poetry As a Possible Metalanguage for Intercultural Dialogue Author: Daniel Roters

Arab-West Report, December 22, 2009 Title: Arabic Poetry as a possible Metalanguage for Intercultural Dialogue Author: Daniel Roters “For me the province of poetry is a private ecstasy made public, and the social role of the poet is to display moments of shared universal epiphanies capable of healing our sense of mortal estrangement—from ourselves, from each other, from our source, from our destiny, from the Divine” (Danial Abdal-Hayy, US-American poet) Introduction The aim of this study is to show how modern Arabic literature and poetry could help in the effort to understand modern Arab society and its problems. At the same time it will be necessary to describe the history of Arabic poetry if we want to understand how important poetry in contemporary Arab society is. This whirlwind tour through the history of Arabic poetry will be restrained to the function of the poet and the role of poetry played in general in Arabic-Islamic history. Indeed the preoccupation with works of modern writers should not only be an issue for organizations working on the improvement of intercultural dialogue. It is also of great importance that the scholarly discourse in Islamic or Middle Eastern Studies recognizes the importance of modern Arabic literature. Arabic literature could be another valuable source of information, in addition to the Qur' ān and Sunnah. If you 1 consider the theory of theologian Hermann Gunkel about the “Sitz im Leben ” (seat in life) and if we question a lyrical or prose text about the formative stage, it is possible to learn much about the society from which an author is addressing his audience. -

SHARJAH FILM PLATFORM SCREENING SCHEDULE 19–26 January 2019

SHARJAH FILM PLATFORM SCREENING SCHEDULE 19–26 January 2019 Programme 1 Friday, 18 January - 9:00 pm Mirage City Cinema Saturday, 26 January - 3:00 pm Sharjah Institute of Theatrical Arts Sharjah Film Platform annually awards Short Film Production Grants in support of film production in the UAE and internationally. Selected through an open call, this year’s grant winners are Abdulrahman Al Madani and Mohammed Al Hammadi, whose films Laymoon and Maryam, respectively, will be premiered at the festival. Al Madani and Al Hammadi will discuss their films after the screenings on opening night. Laymoon (2019) Director: Abdulrahman Al Madani United Arab Emirates Narrative | 16 min Arabic with English subtitles A neglected housewife’s constant attempts to regain her short-tempered husband’s interest in their marriage prove futile. Influenced by her best friend, she realises her efforts need to stretch beyond a wholesome meal. Abdulrahman Al Madani started making films in 2012, focusing particularly on social issues. His first documentary short, The Gamboo3a Revolution (2012), won awards from the Gulf Film Festival and the Abu Dhabi Film Festival, and he also directed the two short films Guilt (2013) and Nagafa (2014). He received a bachelor's degree in applied media studies from the Higher Colleges of Technology, Dubai (2014) and completed a one-year filmmaking diploma programme at the New York Film Academy Abu Dhabi (2015). His thesis film, Beshkara, received its world premiere at the Dubai International Film Festival the same year. Al Madani was born in 1992 in Dubai, where he currently lives and works. Maryam (2019) Director: Mohammed Al Hammadi United Arab Emirates Narrative | 22 min Arabic with English subtitles An ambitious young Emirati’s dream to pursue an acting career in New York is challenged by the sudden of her father and the opposition of her mother, who wants her to marry. -

154 Features Features 155

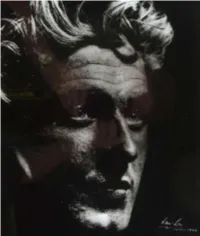

154 Features Features 155 Van Leo from Turkey to Egypt By Martina Corgnati 156 Features The first photographic forays in the Middle East occurred within the Armenian community. In Egypt, legendary figures such as G. Lekegian, who arrived from Istanbul around 1880, kick-started an Armenian led monopoly over photography and the photographic business. Gradually, other photogra- phers began to populate the area around Lekegian’s Cairo studio, located near Opera Square, creating a small “special- ized” neighborhood in both the commercial and ethnic sense. Favored, perhaps, by historical familiarity with images and Christian religion’s acceptance of representational media; Armenians tended to pass on the trade, which at the time could only be learned through experience in the workshops. Due to this process, Armenian photographers were often quite experimental. Armand (Armenak Arzrouni, b. Erzurum 1901 – d. Cairo 1963), Archak, Tartan and Alban (the art name of Aram Arnavoudian, b. Istanbul 1883 – d. Cairo 1961), for example, who arrived in Cairo in the early twentieth century, were some of the first to try “creative” photographic tech- niques that played with variations in composition and points of view. The first photographer Van Leo met in Cairo was an Arme- nian artist called Varjabedian. Still a child, Van Leo regularly visited his provincial photography studio and, years later, Varjabedian would be the one to introduce him to the photog- raphy “temple” in Cairo. This was the name given to the area from Opera Square to Qasr al Nil Street where an abundance of photographic studios and foreign jewelers mingled with Leon (Leovan) Boyadjian, known in the art world as the Egyptian artistic aura. -

Arabic Films

Arabic Films Call # HQ1170 .A12 2007 DVD Catalog record http://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b6528747~S7 TITLE 3 times divorced / a film by Ibtisam Sahl Mara'ana a Women Make Movies release First Hand Films produced for The Second Authority for Television & Radio the New Israeli Foundation for Cinema & Film Gon Productions Ltd Synopsis Khitam, a Gaza-born Palestinian woman, was married off in an arranged match to an Israeli Palestinian, followed him to Israel and bore him six children. When her husband divorced her in absentia in the Sharia Muslim court and gained custody of the children, Khitam was left with nothing. She cannot contact her children, has no property and no citizenship. Although married to an Israeli, a draconian law passed in 2002 barring any Palestinian from gaining Israeli citizenship has made her an illegal resident there. Now she is out on a dual battle, the most crucial of her life: against the court which always rules in favor of the husband, and against the state in a last-ditch effort to gain citizenship and reunite with her children Format DVD format Call # DS119.76 .A18 2008 DVD Catalog record http://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b6514808~S7 TITLE 9 star hotel / Eden Productions Synopsis A look at some of the many Palestinians who illegally cross the border into Israel, and how they share their food, belongings, and stories, as well as a fear of the soldiers and police Format DVD format Call # PN1997 .A127 2000z DVD Catalog record http://library.ohio-state.edu/record=b6482369~S7 TITLE 24 sāʻat ḥubb = 24 hours of love / Aflām al-Miṣrī tuqaddimu qiṣṣah wa-sīnāryū wa-ḥiwār, Fārūq Saʻīd افﻻم المرصي تقدم ؛ قصة وسيناريوا وحوار, فاروق سعيد ؛ / hours of love ساعة حب = ikhrāj, Aḥmad Fuʼād; 24 24 اخراج, احمد فؤاد Synopsis In this comedy three navy officers on a 24 hour pass go home to their wives, but since their wives doubt their loyalty instead of being welcomed they are ignored. -

Ar Risalah) Among the Moroccan Diaspora

. Volume 9, Issue 1 May 2012 Connecting Islam and film culture: The reception of The Message (Ar Risalah) among the Moroccan diaspora Kevin Smets University of Antwerp, Belgium. Summary This article reviews the complex relationship between religion and film-viewing among the Moroccan diaspora in Antwerp (Belgium), an ethnically and linguistically diverse group that is largely Muslim. A media ethnographic study of film culture, including in-depth interviews, a group interview and elaborate fieldwork, indicates that film preferences and consumption vary greatly along socio-demographic and linguistic lines. One particular religious film, however, holds a cult status, Ar Risalah (The Message), a 1976 historical epic produced by Mustapha Akkad that deals with the life of the Prophet Muhammad. The film’s local distribution is discussed, as well as its reception among the Moroccan diaspora. By identifying three positions towards Islam, different modes of reception were found, ranging from a distant and objective to a transparent and subjective mode. It was found that the film supports inter-generational religious instruction, in the context of families and mosques. Moreover, a specific inspirational message is drawn from the film by those who are in search of a well-defined space for Islam in their own lives. Key words: Film and diaspora, media ethnography, Moroccan diaspora, Islam, Ar Risalah, The Message, Mustapha Akkad, religion and media Introduction The media use of diasporic communities has received significant attention from a variety of scholarly fields, uncovering the complex roles that transnational media play in the construction of diasporic connectedness (both ‘internal’ among diasporic communities as well as with countries of origin, whether or not ‘imagined’), the negotiation of identity and the enunciation of socio-cultural belongings.