Tunnels Through the Alps Paul Sharp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: August 6th, 2007 I, __________________Julia K. Baker,__________ _____ hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in: German Studies It is entitled: The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger Dr. Sara Friedrichsmeyer Dr. Todd Herzog The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life-Writing and Documentary Film A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) In the Department of German Studies Of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julia K. Baker M.A., Bowling Green State University, 2000 M.A., Karl Franzens University, Graz, Austria, 1998 Committee Chair: Katharina Gerstenberger ABSTRACT “The Return of the Child Exile: Re-enactment of Childhood Trauma in Jewish Life- Writing and Documentary Film” is a study of the literary responses of writers who were Jewish children in hiding and exile during World War II and of documentary films on the topic of refugee children and children in exile. The goal of this dissertation is to investigate the relationships between trauma, memory, fantasy and narrative in a close reading/viewing of different forms of Jewish life-writing and documentary film by means of a scientifically informed approach to childhood trauma. Chapter 1 discusses the reception of Binjamin Wilkomirski’s Fragments (1994), which was hailed as a paradigmatic traumatic narrative written by a child survivor before it was discovered to be a fictional text based on the author’s invented Jewish life-story. -

A Construction Project Serving Europe – Factfigures

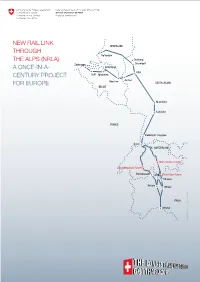

NEW RAIL LINK NEDERLAND THROUGH Rotterdam THE ALPS (NRLA) Duisburg Zeebrugge Düsseldorf A ONCE-IN-A- Antwerpen Köln CENTURY PROJECT Gent Mechelen Aachen FOR EUROPE Montzen DEUTSCHLAND BELGIË Mannheim Karlsruhe FRANCE Freiburg im Breisgau Basel SWITZERLAND Gotthard Base Tunnel Lötschberg Base Tunnel Domodossola Luino Ceneri Base Tunnel Chiasso Novara Milano ITALIA Genova © Federal office of transport FOT transport office of © Federal FACTS AND FIGURES NRLA The New Rail Link through the Alps (NRLA) is the largest railway construction project ever undertaken in Swiss history. It includes the expansion of two north- south axes for the rail link. The main components of the NRLA are the Lötsch- berg Base Tunnel, the Gotthard Base Tunnel and the Ceneri Base Tunnel. Since 2007 Successful operation of the Lötschberg Base Tunnel 11 December 2016 Commissioning of the Gotthard Base Tunnel The world’s longest railway tunnel will be commissioned on schedule on 11 December 2016. Up to 250 freight trains a day will then travel on the Gotthard axis instead of 180 previously. Transalpine rail transport will become more cost-effective, flexible and rapid. 2020 Opening of the Ceneri Base Tunnel 2020 Four-metre corridor on the Gotthard axis The expansion of the Gotthard axis to create a larger tunnel profile is a key part of the Swiss policy of transferring freight from road to rail. It will enable semi- trailers with a four-metre corner height to also be loaded onto railway wagons for transport on the Gotthard axis on a continuous basis. This further fosters the transfer of transalpine freight transport from road to rail. -

“Discover the Captivating History of the Swiss Army Knife at the Victorinox

Victorinox Museum For more than 130 years, Victorinox has embodied quality, functionality and design. In 1884, Karl Elsener established a cutlery workshop and by 1891, he was already supplying the Swiss Armed Forces with knives for the soldiers. When Karl Elsener created the original “Swiss Offi cer’s Knife”, he had no inkling that it would soon conquer the world. Today, the “Swiss Army Knife” is internationally patented and epitomizes more than any other product the world-famous notion of “Swiss made”. “Discover the captivating history of the Swiss Army Knife at the Victorinox Victorinox Brand Store Museum in Brunnen.” Experience the brand world of Victorinox in the Brand Store and fi nd yourself some loyal companions for the adventures of daily life. Apart from pocketknives, household and trade knives, the product line also includes timepieces, travel equipment, fashion and fragrances. The VISITOR CENTER in Brunnen is a fascinating starting point for Location your stay in the Swiss Knife Valley. Stretching across 365 square The VISITOR CENTER with the Victorinox Brand Store & Museum are metres, it tells you all about Victorinox, the Valley’s most beautiful located in Bahnhofstrasse 3 in Brunnen (municipality of Ingenbohl), destinations and other important enterprises in the region. 100 metres from the jetty, 500 metres from the train station of Brunnen. The public bus service stops directly in front of the building (at The small movie theatre features a 15-minute fi lm about the pro- “Brunnen See/Schiff station”). Metered parking nearby. duction of the Victorinox pocketknife, and a 10-minute fi lm about the attractions in the Swiss Knife Valley. -

SWISS REVIEW the Magazine for the Swiss Abroad August 2016

SWISS REVIEW The magazine for the Swiss Abroad August 2016 History at the Gotthard – the opening of the base tunnel A cotton and plastic sandwich – the new CHF 50 banknote Keeping an eye on the surveillance – the Davos-born photographer Jules Spinatsch Switzerland is mobile and Swiss Abroad may be found everywhere on Earth. And you, where are you situated around the globe? And since when? Share your experience and get to know Swiss citizens living nearby… and everywhere else! connects Swiss people across the world > You can also take part in the discussions at SwissCommunity.org > Register now for free and connect with the world SwissCommunity.org is a network set up by the Organisation of the Swiss Abroad (OSA) SwissCommunity-Partner: Contents Editorial 3 Casting your vote – even if it is sometimes a chore 5 Mailbag Hand on heart, did you vote in June? If you did, on how many of the five federal proposals? I tried to form an 6 Focus opinion on all of the initiatives and referenda. I stu The tunnelbuilding nation died the voting documents, read newspapers, watched “Arena” on Swiss television and discussed the issues 10 Economy with family and friends. The new banknotes Admittedly, it was arduous at times: Just the doc uments themselves, which included two hefty book 12 Politics lets, various information sheets and the ballot papers, namely for the five fed Referendum results from 5 June eral proposals – pro public service, unconditional basic income, the milch Proposals for 25 September cow initiative, the amendment to the law on reproductive medicine and an Parmelin’s first few months on the amendment to the Asylum Act – plus, because I live in Baselland, six cantonal Federal Council proposals ranging from supplementary childcare to the “Cantonal parlia ment resolution on the implementation of the pension fund law reform for 17 Culture the pension scheme of the University of Basel under the pension fund of the The alphorn in the modern age canton of BaselStadt – a partnershipbased enterprise”. -

Ticino-Milano Dal 15.12.2019 Erstfeld Ambrì- Orario Dei Collegamenti Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona

Hier wurde der Lago Maggiore 4 mm nach links verschoben Hier wurde der Lago Maggiore 4 mm nach links verschoben Luzern / Zürich Luzern /Lu Züzernrich / Zürich Luzern /Lu Zürizercnh /Lu Züzernrich / Zürich Luzern /Lu Zzüernrich /Lu Zürizercnh / Zürich Luzern /Lu Züzernrich / Zürich Luzern /Lu Züzrernich / Zürich Luzern /Lu Zürizercnh / Zürich Luzern /Lu Zzüriercnh / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern /Erst Zürichfeld Luzern / ZürichErstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Orario dei collegamentiOrario deiMilano collegamentiOrario Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona.Orario dei collegamenti deiMilano collegamentiOrario Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. deiMilano collegamenti Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona.Orario Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. deiMilano collegamenti Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona.Orario Milanodei collegamentiOrario Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. dei collegamentiOrario Milano dei Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. collegamenti Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. Erstfeld Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Erstfeld Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Orario dei collegamenti Ticino-Milano dal 15.12.2019 Erstfeld Ambrì- Orario dei collegamenti Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. GöschenenErstfeld Piotta Faido LaGöschenenvorgo PiottaGöschenenFaido LaGöschenenvorgo Piotta FaidoPiottaLaGöschenenvorgFoaido Lavorgo Piotta Faido LaGöschenenvorgo Piotta Faido LaGöschenenvorgo PiottaGöschenenFaido Lavorgo PiottaGöschenenFaido -

Ticino on the Move

Tales from Switzerland's Sunny South Ticino on theMuch has changed move since 1882, when the first railway tunnel was cut through the Gotthard and the Ceneri line began operating. Mendrisio’sTHE LIGHT Processions OF TRADITION are a moving experience. CrystalsTREASURE in the AMIDST Bedretto THE Valley. ROCKS ChestnutsA PRICKLY are AMBASSADOR a fruit for all seasons. EasyRide: Travel with ultimate freedom. Just check in and go. New on SBB Mobile. Further information at sbb.ch/en/easyride. EDITORIAL 3 A lakeside view: Angelo Trotta at the Monte Bar, overlooking Lugano. WHAT'S NEW Dear reader, A unifying path. Sopraceneri and So oceneri: The stories you will read as you look through this magazine are scented with the air of Ticino. we o en hear playful things They include portraits of men and women who have strong ties with the local area in the about this north-south di- truest sense: a collective and cultural asset to be safeguarded and protected. Ticino boasts vide. From this year, Ticino a local rural alpine tradition that is kept alive thanks to the hard work of numerous young will be unified by the Via del people. Today, our mountain pastures, dairies, wineries and chestnut woods have also been Ceneri themed path. restored to life thanks to tourism. 200 years old but The stories of Lara, Carlo and Doris give off a scent of local produce: of hay, fresh not feeling it. milk, cheese and roast chestnuts, one of the great symbols of Ticino. This odour was also Vincenzo Vela was born dear to the writer Plinio Martini, the author of Il fondo del sacco, who used these words to 200 years ago. -

UNESCO World Heritage Properties in Switzerland February 2021

UNESCO World Heritage properties in Switzerland February 2021 www.whes.ch Welcome Dear journalists, Thank you for taking an interest in Switzerland’s World Heritage proper- ties. Indeed, these natural and cultural assets have plenty to offer: en- chanting cityscapes, unique landscapes, historic legacies and hidden treasures. Much of this heritage was left to us by our ancestors, but nature has also played its part in making the World Heritage properties an endless source of amazement. There are three natural and nine cultur- al assets in total – and as unique as each site is, they all have one thing in common: the universal value that we share with the global community. “World Heritage Experience Switzerland” (WHES) is the umbrella organisation for the tourist network of UNESCO World Heritage properties in Switzerland. We see ourselves as a driving force for a more profound and responsible form of tourism based on respect and appreciation. In this respect we aim to create added value: for visitors in the form of sustainable experiences and for the World Heritage properties in terms of their preservation and appreciation by future generations. The enclosed documentation will offer you the broadest possible insight into the diversity and unique- ness of UNESCO World Heritage. If you have any questions or suggestions, you can contact us at any time. Best regards Kaspar Schürch Managing Director WHES [email protected] Tel. +41 (0)31 544 31 17 More information: www.whes.ch Page 2 Table of contents World Heritage in Switzerland 4 Overview -

A Geological Boat Trip on Lake Lucerne

A geological boat trip on Lake Lucerne Walter Wildi & Jörg Uttinger 2019 h=ps://www.erlebnis-geologie.ch/geoevent/geologische-schiffFahrt-auF-dem-vierwaldstae=ersee-d-e-f/ 1 A geological boat trip on Lake Lucerne Walter Wildi & Jörg Uttinger 2019 https://www.erlebnis-geologie.ch/geoevent/geologische-schifffahrt-auf-dem-vierwaldstaettersee-d-e-f/ Abstract This excursion guide takes you on a steamBoat trip througH a the Oligocene and the Miocene, to the folding of the Jura geological secYon from Lucerne to Flüelen, that means from the mountain range during the Pliocene. edge of the Alps to the base of the so-called "HelveYc Nappes". Molasse sediments composed of erosion products of the rising The introducYon presents the geological history of the Alpine alpine mountains have been deposited in the Alpine foreland from region from the Upper Palaeozoic (aBout 315 million years ago) the Oligocene to Upper Miocene (aBout 34 to 7 Milion years). througH the Mesozoic era and the opening up of the Alpine Sea, Today's topograpHy of the Alps witH sharp mountain peaks and then to the formaYon of the Alps and their glacial erosion during deep valleys is mainly due to the action of glaciers during the last the Pleistocene ice ages. 800,000 years of the ice-ages in the Pleistocene. The Mesozoic (from 252 to 65 million years) was the period of the The cruise starts in Lucerne, on the geological limit between the HelveYc carBonate plaaorm, associated witH a higH gloBal sea Swiss Plateau and the SuBalpine Molasse. Then it leads along the level. -

Rhätische Bahn Und Verleiht Ihr Erscheint Gewissermaßen Als «Kleine Schweiz»

WINTER IN THE GRISONS INVERNO NEI GRIGIONI ON THE PRICE THROVGH THE PREZZO (SWITZERLAND) Fr.180 CON LA 36 Ski-ing 38 Walks 36 Discesa cogli sci 38 Passeggiate neue neve 37 Curling 39 Sleigh drives 37 Curling 39 Cite cone alitta ATTRAVERSO I (SVIZZERA) ZU,C17 Rapperswil Zifrich\ Rorscloch 1Linb'sa-MiincheRnfo tanz-Stutt9art Buchs 0 S TER A GRAUBONDEN()Schwyz Sargans andquart Linthal 14 Altdorf o los ers -lims 0 Reichena '1it/';1*tensto 10 Scuol/ Schuis- : 11 Vuorz 15 Tarasp „•71)"i'S'er:n*ii s Zernez Gbs e en t12Muster Filisur Be csUn Anderr&att Die Zahlen im nebenstehenden Netzbild Bravuogn der Rhatischen Bahn entsprechen den Nummern der betreffenden Karten im Beyer Prospekt. S!Moritz Airolo Bontresin4 6 440 •••••• 00;pizio'Bernina 0Maloja 1:Mesocc 0AlpBrLi*m 16 iavenn'a% .... Campocolgno Bellinzona Tirano \Logarw-AlilaRo Graubunden ist mit seinen 7113 km' Flächeninhalt der größte Kanton der Mesocco, die in den Jahren 1942 und 1943 mit der Rhatischen Bahn ver- Schweiz. Er zählt aber nur 150 000 Einwohner, so daß seine Bevölkerungs- einigt wurden. Die Züge fahren durch 119 Tunnels und Galerien mit einer dichte (21 Einwohner auf einen Quadratkilometer) an letzter Stelle aller Gesamtlänge von 39 km und über 488 Brücken, die zusammen 12 km Kantone steht. lang sind. Die modernen Anlagen, die Betriebssicherheit, die guten Zugs- Ein Blick auf die Schweizerkarte läßt erkennen, daß der geographische verbindungen, die Ausstattung (Speisewagen in den Schnellzügen), die Grundriß Graubtindens demjenigen der Schweiz sehr ähnlich ist ; er Verbauungen, all dies kennzeichnet die Rhätische Bahn und verleiht ihr erscheint gewissermaßen als «kleine Schweiz». -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

The Simplon Tunnel

The Simplon Tunnel THE SIMPLON STORY The commemorative stamp issued this year (1956) celebrated, strictly speaking, only the opening of the first tunnel gallery. The story of the tunnel, one of the greatest engineering feats in railway history, goes back to the year 1877 when M. Lommel, the chief engineer of the "Compagnie du Chemin de Fer", a privately owned undertaking, produced the first plans for the tunnel. The Swiss and Italian governments and private enterprise in both countries agreed, after many years of study, to finance the ambitious project for the building of a 19,803m long tunnel, the cost of which was estimated at the then fantastic sum of over 700 million Swiss francs. A state treaty was concluded between Switzerland and Italy on 25th November 1895 and on 1st August 1898 the first drill was put to the rock near Brig, on the north side of the tunnel. After 6 years and 208 days of almost superhuman effort, at 7.20 in the evening, the last hole had boon drilled - letting light into the tunnel on its south end. It was the 24th of February 1905, a date that made history. Landslides, flooding, avalanches and huge caving-in had been fought and conquered. On 1st June 1906 the first regular train service ran through the Simplon providing the shortest railway link between Northern and Western Europe with the South and the Orient. The First World War interrupted construction of the second gallery and it took many years until in 1922 the tunnel was completed, allowing for two-track traffic. -

Lake Lucerne Walking Holiday from £899 Per Person // 8 Days

Lake Lucerne Walking Holiday From £899 per person // 8 days Take the train to lovely Lucerne and then walk around the lake front and into the mountains on this stunning hiking holiday. Your route will take you via famous peaks, lush gorges and sweeping Alpine vistas with some breathtaking cable car rides along the way. The Essentials What's included Train travel to Lucerne and back to the UK at the end of Standard class rail travel with seat reservations, where your holiday required Lovely mountain resorts in the Lucerne Region 6 nights’ hotel accommodation with breakfast Scenic cableways connecting hiking trails Half fare card for additional rail travel in Switzerland A night in the cultural city of Basel on the way home Cable car rides from Dallenwil to Niederrickenbach and Niederrickenbach to Emmetten Boat crossing from Rütli to Brunnen Tailor make your holiday Luggage transfers between hotels – Lucerne to Küssnacht am Rigi Decide when you would like to travel Detailed itinerary and travel documentation for walks Adapt the route to suit your plans Clearly-presented wallets for your rail tickets and hotel Upgrade hotels and rail journeys vouchers Add extra nights, destinations and/or tours All credit card surcharges and complimentary delivery of your travel documents PLEASE NOTE: This holiday runs daily between 2 May and 18 October 2020 - Suggested Itinerary - Day 1 - London To Lucerne Take the train from London St Pancras across the English Channel to Paris and then connect onto a TGV Lyria service to Basel on the Swiss border. From here, it’s a short journey south to Lucerne.