Herod the Great's Unique Jerusalem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Can We Know the Way?

How Can We Know the Way? Sermon for the Fifth Sunday of Easter The Ninth Sunday of Our Pandemic Crisis May 10, 2020 Bethany Congregational Church, United Church of Christ Foxborough, Massachusetts Rev. Bruce A. Greer, Interim Pastor Text: John 14:5 “Thomas said to [Jesus]: ‘Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?’” I. When Thomas asked Jesus “How can we know the way?” he wasn’t asking for directions. No Google Map or GPS device could answer his question. We ask questions like this when we are disoriented, when our resources are uncertain and the outcome is unknown. A question like this cries out for guidance and assurance, not directions from Point A to Point B. Put yourself in the context of the question. Jesus gathered his disciples for what would be their last supper.1 His death was imminent, so he said to his disciples: “Do not let your hearts be trou- bled. Believe in God, believe also in me.”2 He assured them of God’s presence and guidance on their way forward. He assumed that the disciples already knew this. Throughout John’s Gospel, we find the disciples consistently confused by Jesus, repeatedly miss- ing the point. What did Jesus mean? Where was he going? What will happen to him and to their movement? It was an anxious time filled with tension and concern. You can feel it in Thomas’s question: “Lord we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?”3 We’ve all been in situations like this, wondering about the way forward. -

Bimt Seminar Handout

Bringing the Bible to LifeSeminar Physical Settings of the Bible Seminar Topics Session I: Introduction - “Physical Settings of the Bible” Session II: “Connecting the Dots” - Geography of Israel Session III: Archaeology & the Bible Session IV: Life & Ministry of Jesus Session V: Jerusalem in the Old Testament Session VI: Jerusalem in the Days of Jesus Session VII: Manners & Customs of the Bible Goals & Objectives • To gain a new and exciting “3-D” perspective of the land of the Bible. • To begin understanding the “playing board” of the Bible. • To pursue the adventure of “connecting the dots” between the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. • To appreciate the context of the stories of the Bible, including the life and ministry of Jesus. • To grow in our walk of faith with the God of redemptive history. 2 Bringing the Bible to Life Seminar About Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours (BIMT) was created 25 years ago (originally called Biblical Israel Tours) out of a passion for leading people to a personalized study tour experience of Israel, the land of the Bible. The ministry expanded in 2016. BIMT is now a support-based evangelical support-based non-profit 501c3 tax-exempt ministry dedicated to helping people “connect the dots” between the context of the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. The two-fold purpose of BIMT is: 1. Leading highly biblical study-discipleship tours to Israel and other lands of the Bible, and 2. Providing “Physical Settings of the Bible” teaching and discipleship training for churches and schools. It is our prayer that BIMT helps people to not only grow in a deeper understanding (e.g. -

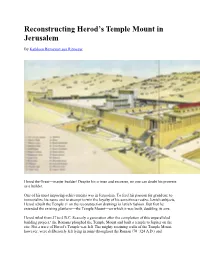

Reconstructing Herod's Temple Mount in Jerusalem

Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem By Kathleen RitmeyerLeen Ritmeyer Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder. One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size. Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020 (3 credits; MW 10:05-11:25; Oegema; Zoom & Recorded) Instructor: Prof. Dr. Gerbern S. Oegema Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University 3520 University Street Office hours: by appointment Tel. 398-4126 Fax 398-6665 Email: [email protected] Prerequisite: This course presupposes some basic knowledge typically but not exclusively acquired in any of the introductory courses in Hebrew Bible (The Religion of Ancient Israel; Literature of Ancient Israel 1 or 2; The Bible and Western Culture), New Testament (Jesus of Nazareth, New Testament Studies 1 or 2) or Rabbinic Judaism. Contents: The course is meant for undergraduates, who want to learn more about the history of Ancient Judaism, which roughly dates from 300 BCE to 200 CE. In this period, which is characterized by a growing Greek and Roman influence on the Jewish culture in Palestine and in the Diaspora, the canon of the Hebrew Bible came to a close, the Biblical books were translated into Greek, the Jewish people lost their national independence, and, most important, two new religions came into being: Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. In the course, which is divided into three modules of each four weeks, we will learn more about the main historical events and the political parties (Hasmonaeans, Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, etc.), the religious and philosophical concepts of the period (Torah, Ethics, Freedom, Political Ideals, Messianic Kingdom, Afterlife, etc.), and the various Torah interpretations of the time. A basic knowledge of this period is therefore essential for a deeper understanding of the formation of the two new religions, Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, and for a better understanding of the growing importance, history and Biblical interpretation have had for Ancient Judaism. -

THE CTU 50TH ANNIVERSARY Bible Land Tours with Fr. Don Senior, CP

THE CTU 50TH ANNIVERSARY Bible Land Tours with Fr. Don Senior, CP From the very beginning of its 50th year life-span, Catholic Theological Union has had a deep connection with the lands of the Bible through its renowned Bible department. Each year CTU students and faculty have spent a semester abroad studying in Jerusalem and exploring the adjacent biblical sites in Jordan, Egypt, Greece, and Turkey. Beginning in 1988 and continuing every year since, Rev. Donald Senior, CP, professor of New Testament and President Emeritus, has conducted biblical tours designed for board members and friends of CTU. Nearly 800 people have participated in these special tours that include deluxe travel, five-star hotels, opportunities for worship at sacred sites, and expert biblical commentary on archaeological sites that form the historical foundations of our Christian faith. To celebrate its 50th anniversary year (2018–2019) as a premier school of theology, CTU will sponsor three special tours of the biblical lands: The Birth of Christianity: The Holyland: The Land of Egypt Greece and Turkey Israel and Jordan OCTOBER 5 – 20, 2018 FEBRUARY 8 – 18, 2019 JUNE 15 – 28, 2019 fr. donald senior, cp professor of new testament and president emeritus My work has focused on the study and interpretation of the Gospels, the Pauline literature, 1 Peter, and New Testament archaeology. Along with teaching, I have also been involved in administration of theological education and with exploration of the biblical lands in the Middle East. I am currently working as a General Editor of a new edition of the Jerome Biblical Commentary and writing a full-length biography of noted Catholic Scripture scholar Raymond E. -

Crossroads 360 Virtual Tour Script Edited

Crossroads of Civilization Virtual Tour Script Note: Highlighted text signifies content that is only accessible on the 360 Tour. Welcome to Crossroads of Civilization. We divided this exhibit not by time or culture, but rather by traits that are shared by all civilizations. Watch this video to learn more about the making of Crossroads and its themes. Entrance Crossroads of Civilization: Ancient Worlds of the Near East and Mediterranean Crossroads of Civilization looks at the world's earliest major societies. Beginning more than 5,000 years ago in Egypt and the Near East, the exhibit traces their developments, offshoots, and spread over nearly four millennia. Interactive timelines and a large-scale digital map highlight the ebb and flow of ancient cultures, from Egypt and the earliest Mesopotamian kingdoms of the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, to the vast Persian, Hellenistic, and finally Roman empires, the latter eventually encompassing the entire Mediterranean region. Against this backdrop of momentous historical change, items from the Museum's collections are showcased within broad themes. Popular elements from classic exhibits of former years, such as our Greek hoplite warrior and Egyptian temple model, stand alongside newly created life-size figures, including a recreation of King Tut in his chariot. The latest research on our two Egyptian mummies features forensic reconstructions of the individuals in life. This truly was a "crossroads" of cultural interaction, where Asian, African, and European peoples came together in a massive blending of ideas and technologies. Special thanks to the following for their expertise: ● Dr. Jonathan Elias - Historical and maps research, CT interpretation ● Dr. -

The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 A.D.)

The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 A.D.) Leen Ritmeyer • 08/03/2018 This post was originally published on Leen Ritmeyer’s website Ritmeyer Archaeological Design. It has been republished with permission. Visit the website to learn more about the history of the Temple Mount and follow Ritmeyer Archaeological Design on Facebook. Following on from our previous drawing, the Temple Mount during the Hellenistic and Hasmonean periods, we now examine the Temple Mount during the Herodian period. This was, of course, the Temple that is mentioned in the New Testament. Herod extended the Hasmonean Temple Mount in three directions: north, west and south. At the northwest corner he built the Antonia Fortress and in the south, the magnificent Royal Stoa. In 19 B.C. the master-builder, King Herod the Great, began the most ambitious building project of his life—the rebuilding of the Temple and the Temple Mount in lavish style. To facilitate this, he undertook a further expansion of the Hasmonean Temple Mount by extending it on three sides, to the north, west and south. Today’s Temple Mount boundaries still reflect this enlargement. The cutaway drawing below allows us to recap on the development of the Temple Mount so far: King Solomon built the First Temple on the top of Mount Moriah which is visible in the center of this drawing. This mountain top can be seen today, inside the Islamic Dome of the Rock. King Hezekiah built a square Temple Mount (yellow walls) around the site of the Temple, which he also renewed. -

The Argument from Miracles: a Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth

The Argument from Miracles: A Cumulative Case for the Resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth Introduction It is a curiosity of the history of ideas that the argument from miracles is today better known as the object of a famous attack than as a piece of reasoning in its own right. It was not always so. From Paul’s defense before Agrippa to the polemics of the orthodox against the deists at the heart of the Enlightenment, the argument from miracles was central to the discussion of the reasonableness of Christian belief, often supplemented by other considerations but rarely omitted by any responsible writer. But in the contemporary literature on the philosophy of religion it is not at all uncommon to find entire works that mention the positive argument from miracles only in passing or ignore it altogether. Part of the explanation for this dramatic change in emphasis is a shift that has taken place in the conception of philosophy and, in consequence, in the conception of the project of natural theology. What makes an argument distinctively philosophical under the new rubric is that it is substantially a priori, relying at most on facts that are common knowledge. This is not to say that such arguments must be crude. The level of technical sophistication required to work through some contemporary versions of the cosmological and teleological arguments is daunting. But their factual premises are not numerous and are often commonplaces that an educated nonspecialist can readily grasp – that something exists, that the universe had a beginning in time, that life as we know it could flourish only in an environment very much like our own, that some things that are not human artifacts have an appearance of having been designed. -

Daniel R. Schwartz from the Maccabees to Masada

Daniel R. Schwartz From the Maccabees to Masada: On Diasporan Historiography of the Second Temple Period Around the time Prof. Oppenheimer invited me to this conference, I was prepar- ing the introduction to my translation of II Maccabees, and had come to the part where I was going to characterize II Maccabees as a typical instance of diasporan historiography. I was thinking, first of all, about the comparison of such passages as I Macc 1:20-23 with II Macc 5:15-16, which both describe Antiochus IV Epiphanes' robbery of the Temple of Jerusalem: I Macc 1:20-23: He went up against Israel and came to Jerusalem with a strong force. He ar- rogantly entered the sanctuary and took the golden altar, the lampstand for the light, and all its utensils. He took also the table for the bread of the Presence, the cups for drink offerings, the bowls, the golden censers, the curtain, the crowns, and the gold decoration on the front of the temple; he stripped it all off. He took the silver and the gold, and the costly utensils... (Revised Standard Version) II Macc 5:15—16: Not content with this (i.e., slaughter and enslavement), Antiochus dared to enter the most holy temple in all the world, guided by Menelaus, who had become a traitor both to the laws and to his country. He took the holy vessels with his polluted hands, and swept away with profane hands the votive offerings which other kings had made to enhance the glory and honor of the place. -

Golgotha and the Holy Sepulchre," Which Sir C

109 'vjOLGOTHA AND THE Holy Sepulchre BY THE LATE MAJOR GENERAL SIR C.W.WILSON K.CB., Etc, Etc., Etc. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924028590499 """"'"'" '""'"' DS 109.4:W74 3 1924 028 590 499 COINS OF ROMAN EMPERORS. GOLGOTHA AND THE HOLY SEPULCHRE BY THE LATE MAJOR-GENERAL SIR C. W. WILSON, R.E., K.C.B., K.C.M.G., F.R.S., D.C.L., LL.D. EDITED BY COLONEL SIR C. M. WATSON, R.E., K.C.M.G., C.B., M.A. f,-f (».( Published by THE COMMITTEE OF THE PALESTINE EXPLORATION FUND, 38, Conduit Street, London, W. igo6 All rights reserved. HAKKISON AKD SOSS, PIUSTEH5 IN OBMNAEY 10 HIS MAJliSTV, ST MAHTIX'S LAK'li, LOSDOiV, W.C. CONTENTS. PAGE Introductory Note vii CHAPTEE I. Golgotha—The Name ... 1 CHAPTEE II. Was there a Public Place op Execution at Jerusalem in THE Time of Christ? 18 CHAPTER III. The Topography of Jerusalem at the Time op the Crucifixion 24 CHAPTER IV. The Position of Golgotha—The Bible Narrative 30 CHAPTER V. On the Position op certain Places mentioned in the Bible Narrative—Gethsemane—The House of Caiaptias —The Hall op the Sanhedein—The Pr^torium ... 37 CHAPTEE VI. The Arguments in Favour op the Authenticity of the Traditional Sites 45 CHAPTER VII. The History op Jerusalem, a.d. 33-326 49 Note on the Coins of JElia 69 CHAPTEE VIII. -

Underground Jerusalem: the Excavation Of

Underground Jerusalem The excavation of tunnels, channels, and underground spaces in the Historic Basin 2015 >> Introduction >> Underground excavation in Jerusalem: From the middle of the 19th century to the Six Day War >> Tunnel excavations following the Six Day War >> Tunnel excavations under archaeological auspices >> Ancient underground complexes >> Underground tunnels >> Tunnel excavations as narrative >> Summary and conclusions >> Maps >> Endnotes Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Emek Shaveh is an organization of archaeologists and heritage professionals focusing on the role of tangible cultural heritage in Israeli society and in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We view archaeology as a resource for strengthening understanding between different peoples and cultures. September 2015 Introduction Underground excavation in Jerusalem: From the middle of the The majority of the area of the Old City is densely built. As a result, there are very few nineteenth century until the Six Day War open spaces in which archaeological excavations can be undertaken. From a professional The intensive interest in channels, underground passages, and tunnels, ancient and modern, standpoint, this situation obligates the responsible authorities to restrict the number of goes back one 150 years. At that time the first European archaeologists in Jerusalem, aided excavations and to focus their attention on preserving and reinforcing existing structures. by local workers, dug deep into the heart of the Holy City in order to understand its ancient However, the political interests that aspire to establish an Israeli presence throughout the topography and the nature of the structures closest to the Temple Mount. Old City, including underneath the Muslim Quarter and in the nearby Palestinian village The British scholar Charles Warren was the first and most important of those who excavated of Silwan, have fostered the decision that intensive underground excavations must be underground Jerusalem.