Daniel R. Schwartz from the Maccabees to Masada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAU Archaeology the Jacob M

TAU Archaeology The Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities | Tel Aviv University Number 4 | Summer 2018 Golden Jubilee Edition 1968–2018 TAU Archaeology Newsletter of The Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and The Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities Number 4 | Summer 2018 Editor: Alexandra Wrathall Graphics: Noa Evron Board: Oded Lipschits Ran Barkai Ido Koch Nirit Kedem Contact the editors and editorial board: [email protected] Discover more: Institute: archaeology.tau.ac.il Department: archaeo.tau.ac.il Cover Image: Professor Yohanan Aharoni teaching Tel Aviv University students in the field, during the 1969 season of the Tel Beer-sheba Expedition. (Courtesy of the Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University). Photo retouched by Sasha Flit and Yonatan Kedem. ISSN: 2521-0971 | EISSN: 252-098X Contents Message from the Chair of the Department and the Director of the Institute 2 Fieldwork 3 Tel Shimron, 2017 | Megan Sauter, Daniel M. Master, and Mario A.S. Martin 4 Excavation on the Western Slopes of the City of David (‘Giv’ati’), 2018 | Yuval Gadot and Yiftah Shalev 5 Exploring the Medieval Landscape of Khirbet Beit Mamzil, Jerusalem, 2018 | Omer Ze'evi, Yelena Elgart-Sharon, and Yuval Gadot 6 Central Timna Valley Excavations, 2018 | Erez Ben-Yosef and Benjamin -

Honigmanonigman - 9780520275584.Indd9780520275584.Indd 1 228/06/148/06/14 2:382:38 PMPM 2 General Introduction

General Introduction SUMMARY Th e fi rst and second books of Maccabees narrate events that occurred in Judea from the 170s through the 150s and eventually led to the rise of the Hasmonean dynasty: the toppling of the last high priest of the Oniad dynasty, the transforma- tion of Jerusalem into a Greek polis, Antiochos IV’s storming of Jerusalem, his desecration of the temple and his so-called persecution of the Jews, the liberation of the city and rededication of the temple altar by Judas Maccabee, the foundation of the commemorative festival of Hanukkah, and the subsequent wars against Seleukid troops. 1 Maccabees covers the deeds of Mattathias, the ancestor of the Maccabean/Hasmonean family, and his three sons, Judas, Jonathan, and Simon, taking its story down to the establishment of the dynastic transmission of power within the Hasmonean family when John, Simon’s son, succeeded his father; whereas 2 Maccabees, which starts from Heliodoros’s visit to Jerusalem under the high priest Onias III, focuses on Judas and the temple rededication, further dis- playing a pointed interest in the role of martyrs alongside that of Judas. Because of this diff erence in chronological scope and emphasis, it is usually considered that 1 Maccabees is a dynastic chronicle written by a court historian, whereas 2 Macca- bees is the work of a pious author whose attitude toward the Hasmoneans has been diversely appreciated—from mild support, through indiff erence, to hostility. Moreover, the place of redaction of 2 Maccabees, either Jerusalem or Alexandria, is debated. Both because of its comparatively fl amboyant style and the author’s alleged primarily religious concerns, 2 Maccabees is held as an unreliable source of evidence about the causes of the Judean revolt. -

Print Friendly Version

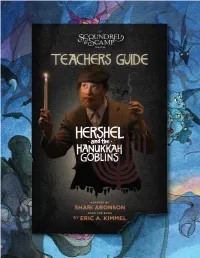

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 The Holiday of Hanukkah 5 Judaism and the Jewish Diaspora 8 Ashkenazi Jews and Yiddish 9 Latkes! 10 Pickles! 11 Body Mapping 12 Becoming the Light 13 The Nigun 14 Reflections with Playwright Shari Aronson 15 Interview with Author Eric Kimmel 17 Glossary 18 Bibliography Using the Guide Welcome, Teachers! This guide is intended as a supplement to the Scoundrel and Scamp’s production of Hershel & The Hanukkah Goblins. Please note that words bolded in the guide are vocabulary that are listed and defined at the end of the guide. 2 Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins Teachers Guide | The Scoundrel & Scamp Theatre The Holiday of Hanukkah Introduction to Hanukkah Questions: In Hebrew, the word Hanukkah means inauguration, dedication, 1. What comes to your mind first or consecration. It is a less important Jewish holiday than others, when you think about Hanukkah? but has become popular over the years because of its proximity to Christmas which has influenced some aspects of the holiday. 2. Have you ever participated in a Hanukkah tells the story of a military victory and the miracle that Hanukkah celebration? What do happened more than 2,000 years ago in the province of Judea, you remember the most about it? now known as Palestine. At that time, Jews were forced to give up the study of the Torah, their holy book, under the threat of death 3. It is traditional on Hanukkah to as their synagogues were taken over and destroyed. A group of eat cheese and foods fried in oil. fighters resisted and defeated this army, cleaned and took back Do you eat cheese or fried foods? their synagogue, and re-lit the menorah (a ceremonial lamp) with If so, what are your favorite kinds? oil that should have only lasted for one night but that lasted for eight nights instead. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020 (3 credits; MW 10:05-11:25; Oegema; Zoom & Recorded) Instructor: Prof. Dr. Gerbern S. Oegema Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University 3520 University Street Office hours: by appointment Tel. 398-4126 Fax 398-6665 Email: [email protected] Prerequisite: This course presupposes some basic knowledge typically but not exclusively acquired in any of the introductory courses in Hebrew Bible (The Religion of Ancient Israel; Literature of Ancient Israel 1 or 2; The Bible and Western Culture), New Testament (Jesus of Nazareth, New Testament Studies 1 or 2) or Rabbinic Judaism. Contents: The course is meant for undergraduates, who want to learn more about the history of Ancient Judaism, which roughly dates from 300 BCE to 200 CE. In this period, which is characterized by a growing Greek and Roman influence on the Jewish culture in Palestine and in the Diaspora, the canon of the Hebrew Bible came to a close, the Biblical books were translated into Greek, the Jewish people lost their national independence, and, most important, two new religions came into being: Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. In the course, which is divided into three modules of each four weeks, we will learn more about the main historical events and the political parties (Hasmonaeans, Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, etc.), the religious and philosophical concepts of the period (Torah, Ethics, Freedom, Political Ideals, Messianic Kingdom, Afterlife, etc.), and the various Torah interpretations of the time. A basic knowledge of this period is therefore essential for a deeper understanding of the formation of the two new religions, Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, and for a better understanding of the growing importance, history and Biblical interpretation have had for Ancient Judaism. -

Masada National Park Sources Jews Brought Water to the Troops, Apparently from En Gedi, As Well As Food

Welcome to The History of Masada the mountain. The legion, consisting of 8,000 troops among which were night, on the 15th of Nissan, the first day of Passover. ENGLISH auxiliary forces, built eight camps around the base, a siege wall, and a ramp The fall of Masada was the final act in the Roman conquest of Judea. A made of earth and wooden supports on a natural slope to the west. Captive Roman auxiliary unit remained at the site until the beginning of the second Masada National Park Sources Jews brought water to the troops, apparently from En Gedi, as well as food. century CE. The story of Masada was recorded by Josephus Flavius, who was the After a siege that lasted a few months, the Romans brought a tower with a commander of the Galilee during the Great Revolt and later surrendered to battering ram up the ramp with which they began to batter the wall. The The Byzantine Period the Romans at Yodfat. At the time of Masada’s conquest he was in Rome, rebels constructed an inner support wall out of wood and earth, which the where he devoted himself to chronicling the revolt. In spite of the debate Romans then set ablaze. As Josephus describes it, when the hope of the rebels After the Romans left Masada, the fortress remained uninhabited for a few surrounding the accuracy of his accounts, its main features seem to have been dwindled, Eleazar Ben Yair gave two speeches in which he convinced the centuries. During the fifth century CE, in the Byzantine period, a monastery born out by excavation. -

The Holy Land & Jordan

RouteThe Holy 66 - LandThe Mother & Jordan Road Walking in the Footsteps of Jesus in the Footsteps Walking November 1 - 13, 2018 (13 days) HIGHLIGHTS Int’l Many sights that Jesus walked and taught Travel in Jordan includes: including: Machaerus, ruins of fortress of The Baptism Site of Jesus in the Herod the Great Jordan River Petra Cana Mt Nebo Caesarea Phillippi A Boat Ride on the Sea of Galilee Nazareth, the Mount of Precipice Mount of Beatitudes Ancient Sites including: Capernaum Megiddo The Garden of Gethsemane Beit Shean Mount of Olives…the Palm Belvoir Crusader Castle Sunday Road Masada The Garden Tomb and Golgatha Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem Jerusalem...the old City including: Qumran, site of the finding of Dead Sea The Via Delarosa Scrolls Church of the Holy Sepulchre Bethlehem: Sea of Galilee with a “Jesus” Boat Church of the Nativity Shepherds Field Special Times of Worship To guarantee availability, make your reservation by July 16th! After this date, call for availability. 145 Day 1 – Depart the United States and God defeated 450 prophets of Baal with fire from heaven (1 From your door to Israel we travel today. Your R&J Tour Director Kings 18). We continue to Nazareth (Luke 1 & 2) and visit the will make sure all goes well as we check in at the airport and board Church of the Annunciation where tradition holds that the Annun- our plane. After dinner is served, sit back and relax, enjoying the ciation took place. From here we continue to the Mt. of Precipice, on-flight entertainment as you prepare for this exciting adventure of the traditional site of the cliff that an angry mob attempted to throw a lifetime, walking where Jesus walked. -

Israel Land of Cultural Treasures

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 28 Travele rs JO URNEY Israel Land of Cultural Treasures Inspiring Moments >Experience Israel’s diverse religious heritage by visiting historical sites steeped in Christianity, Judaism and Islam. INCLUDED FEATURES >Tour cosmopolitan Tel Aviv and Old Jaffa on the Mediterranean coast. ACCOMMODATIONS ITINERARY (With baggage handling.) Day 1 Depart gateway city A >Engage with a local Druze family – Two nights in Tel Aviv, Israel, at the Day 2 Arrive in Tel Aviv while enjoying lunch in their home. first-class Carlton Tel Aviv. Day 3 Tel Aviv >Take a sensory journey in Jerusalem’s – Two nights in Tiberias at the first- Day 4 Tel Aviv | Caesarea | Akko | Machane Yehuda market. class Mizpe Hayamim Hotel. Tiberias >Discover the stark beauty of the Dead – Four nights in Jerusalem at the first- Day 5 Sea of Galilee | Tabgha | Sea, a unique, natural phenomenon. class David Citadel. Mount of Beatitudes | Capernaum | Tiberias >Savor crisp falafels and buttery TRANSFERS olive oils, Israel’s delectable flavors. – All deluxe motor coach transfers Day 6 Megiddo | Haifa | Jerusalem in the Land Program and baggage Day 7 Jerusalem >Experience six UNESCO World handling. Day 8 Jerusalem Heritage sites. EXTENSIVE MEAL PROGRAM Day 9 Masada | Ein Bokek | Jerusalem – Eight breakfasts, five lunches and three Day 10 Transfer to Tel Aviv airport and A dinners, including a Farewell Dinner; depart for gateway city Jaffa tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine AFlights and transfers included for AHI FlexAir participants. with dinner. Note: Itinerary may change due to local conditions. – Sample authentic regional specialties Walking is required on many excursions, and surfaces during meals at local restaurants. -

Day 6 Wednesday March 8 Masada Ein-Gedi Mount of Olives Palm

Day 6 Wednesday March 8 2023 Masada Ein-Gedi Mount of Olives Palm Sunday Walk Tomb of Prophets Garden of Gethsemane Masada Suggested Reading: The Dove Keepers by Alice Hoffman // Josephus, War of the Jews (book 7) Masada is located on a steep and isolated hill on the edge of the Judean desert mountains, on the shores of the Dead Sea. It was the last and most important fortress of the great Jewish rebellion against Rome (66-73 AD), and one of the most impressive archaeological sites in Israel. The last stand of the Jewish freedom fighters ended in tragic events in its last days, which were thoroughly detailed in the accords of the Roman historian of that period, Josephus Flavius. Masada became one of the Jewish people's greatest icons, and a symbol of humanity's struggle for freedom from oppression. Israeli soldiers take an oath here: "Masada shall not fall again." Masada is located on a diamond-shaped flat plateau (600M x 200M, 80 Dunam or 8 Hectares). The hill is surrounded by deep gorges, at a height of roughly 440M above the Dead sea level. During the Roman siege it was surrounded with a 4KM long siege wall (Dyke), with 8 army camps (A thru G) around the hill. Calendar Event 1000BC David hides in the desert fortresses (Masada?) 2nd C BC Hasmonean King (Alexander Jannaeus?) fortifies the hill 31 BC Major earthquake damages the Hasmonean fortifications 24BC Herod the great builds the winter palace and fort 4BC Herod dies; Romans station a garrison at Masada 66AD Head of Sicarii zealots, Judah Galilee, is murdered Eleazar Ben-Yair flees to Masada, establishes and commands a community of zealots 67AD Sicarii sack Ein Gedi on Passover eve, filling up their storerooms with the booty 66-73AD Great Revolt of the Jews against the Romans 70AD Jerusalem is destroyed by Romans; last zealots assemble in Masada (total 1,000), commanded by Eleazar Ben-Yair 73AD Roman 10th Legion under Flavius Silvia, lay a siege; build 8 camps, siege wall & ramp 73AD After several months the Romans penetrate the walls with tower and battering ram. -

Chanukah Activity Pack 2020

TTHHEE GGRREEAATT SSYYNNAAGGOOGGUUEE CCHHAANNUUKKAAHH ActivityActivity PackPack 22002200 -- 55778811 T H E S T O R Y O F C H A N U K A H A long, long time ago in the land of Israel, the most special place for the Jewish people was the Temple in Jerusalem. The Temple contained many beautiful objects, including a tall, golden menorah. Unlike menorahs of today, this one had seven (rather than nine) branches. Instead of being lit by candles or light bulbs, this menorah burned oil. Every evening, oil would be poured into the cups that sat on top of the menorah. The Temple would be filled with shimmering light. At the time of the Hanukkah story, a mean king named Antiochus ruled over the land of Israel. “I don’t like these Jewish people,” declared Antiochus. “They are so different from me. I don’t celebrate Shabbat or read from the Torah, so why should they?” Antiochus made many new, cruel rules. “No more celebrating Shabbat! No more going to the Temple, and no more Torah!” shouted Antiochus. He told his guards to go into the Temple and make a mess. They brought mud, stones, and garbage into the Temple. They broke furniture and knocked things down; they smashed the jars of oil that were used to light the menorah. Antiochus and his soldiers made the Jews feel sad and angry. A Jewish man named Judah Maccabee said, “We must stop Antiochus! We must think of ways to make him leave the land of Israel.” At first, Judah’s followers, called the Maccabees, were afraid. -

1 Maccabees, Chapter 1

USCCB > Bible 1 MACCABEES, CHAPTER 1 From Alexander to Antiochus. 1 a After Alexander the Macedonian, Philip’s son, who came from the land of Kittim,* had defeated Darius, king of the Persians and Medes, he became king in his place, having first ruled in Greece. 2 He fought many battles, captured fortresses, and put the kings of the earth to death. 3 He advanced to the ends of the earth, gathering plunder from many nations; the earth fell silent before him, and his heart became proud and arrogant. 4 He collected a very strong army and won dominion over provinces, nations, and rulers, and they paid him tribute. 5 But after all this he took to his bed, realizing that he was going to die. 6 So he summoned his noblest officers, who had been brought up with him from his youth, and divided his kingdom among them while he was still alive. 7 Alexander had reigned twelve years* when he died. 8 So his officers took over his kingdom, each in his own territory, 9 and after his death they all put on diadems,* and so did their sons after them for many years, multiplying evils on the earth. 10 There sprang from these a sinful offshoot, Antiochus Epiphanes, son of King Antiochus, once a hostage at Rome. He became king in the one hundred and thirty-seventh year* of the kingdom of the Greeks. Lawless Jews. 11 b In those days there appeared in Israel transgressors of the law who seduced many, saying: “Let us go and make a covenant with the Gentiles all around us; since we separated from them, many evils have come upon us.” 12 The proposal was agreeable; 13 some from among the people promptly went to the king, and he authorized them to introduce the ordinances of the Gentiles. -

Plotting Antiochus's Persecution

JBL123/2 (2004) 219-234 PLOTTING ANTIOCHUS'S PERSECUTION STEVEN WEITZMAN [email protected] Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405-7005 The history of religious persecution could be said to have begun in 167 B.C.E. when the Seleucid king Antiochus IV issued a series of decrees outlawing Jewish religious practice. According to 1 Maccabees, anyone found with a copy of the Torah or adhering to its laws—observing the Sabbath, for instance, or practicing circumcision—was put to death. Jews were compelled to build altars and shrines to idols and to sacrifice pigs and other unclean animals. The temple itself was desecrated by a "desolating abomination" built atop the altar of burnt offering. The alternative account in 2 Maccabees adds to the list of outrages: the temple was renamed for Olympian Zeus, and the Jews were made to walk in a procession honoring the god Dionysus. Without apparent precedent, the king decided to abolish an entire religion, suppressing its rites, flaunting its taboos, forcing the Jews to follow "customs strange to the land." Antiochus IV s persecution of Jewish religious tradition is a notorious puz zle, which the great scholar of the period Elias Bickerman once described as "the basic and sole enigma in the history of Seleucid Jerusalem."1 Earlier for eign rulers of the Jews in Jerusalem, including Antiochus s own Seleucid fore bears, were not merely tolerant of the religious traditions of their subjects; they often invested their own resources to promote those traditions.2 According to Josephus, Antiochus III, whose defeat of the Ptolemaic kingdom at the battle of Panium in 200 B.C.E.