The Limestone 2020 the LIMESTONE REVIEW EDITORIAL BOARD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

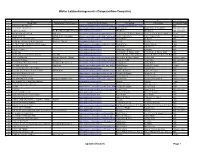

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

EXCEL LATZKO MUZIK CATALOG for PDF.Xlsx

Walter Latzko Arrangements (Computer/Non-Computer) A B C D E F 1 Song Title Barbershop Performer(s) Link or E-mail Address Composer Lyricist(s) Ensemble Type 2 20TH CENTURY RAG, THE https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/the-20th-century-rag-digital-sheet-music/21705300 Male 3 "A"-YOU'RE ADORABLE www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/a-you-re-adorable-digital-sheet-music/21690032Sid Lippman Buddy Kaye & Fred Wise Male or Female 4 A SPECIAL NIGHT The Ritz;Thoroughbred Chorus [email protected] Don Besig Don Besig Male or Female 5 ABA DABA HONEYMOON Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/aba-daba-honeymoon-digital-sheet-music/21693052Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Female 6 ABIDE WITH ME Buffalo Bills; Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/abide-with-me-digital-sheet-music/21674728Henry Francis Lyte Henry Francis Lyte Male or Female 7 ABOUT A QUARTER TO NINE Marquis https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/about-a-quarter-to-nine-digital-sheet-music/21812729?narrow_by=About+a+Quarter+to+NineHarry Warren Al Dubin Male 8 ACADEMY AWARDS MEDLEY (50 songs) Montclair Chorus [email protected] Various Various Male 9 AC-CENT-TCHU-ATE THE POSITIVE (5-parts) https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/ac-cent-tchu-ate-the-positive-digital-sheet-music/21712278Harold Arlen Johnny Mercer Male 10 ACE IN THE HOLE, THE [email protected] Cole Porter Cole Porter Male 11 ADESTES FIDELES [email protected] John Francis Wade unknown Male 12 AFTER ALL [email protected] Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Male 13 AFTER THE BALL/BOWERY MEDLEY Song Title [email protected] Charles K. -

The Bottom Shelf Review Wilson College 2009

The Bottom Shelf Review Wilson College 2009 Edited by: Jessica Carnes and Jess Domanico Advised by: Dr. Michael G. Cornelius Review Staff: Kayla Chagnon, Suzanne Cole, and Nicole Twigg My Mother’s Hands Debbie Arthur I think of my mother and I think of her hands; Why? When looking back over my life, all of the things that I seem to remember about her, she was using her hands I remember when those hands patched walls with plaster. They took off rooms and rooms of wallpaper; painted every wall in our home with every color of the rainbow. They carried coal to the furnace to keep us warm in the winter; and dug out the cellar to store that coal. Those hands took care of her children, digging stones out of our knees, putting bandage upon bandage on so many cuts and bruises to make them better. They smacked us when we disobeyed and marched us to church 3 times a week. They took care of us when we were sick, patting our hot little heads; feeding us when we were too sick to eat, and with all those kids that was a lot of feeding. They tucked warm blankets around each of her children to keep out the cold at night. They folded in prayer each and every day to talk to God. You would think they would be worn out with all that work they have done over the years for so many of us. But they are not. When I walk into that house today, stressed or upset, those hands on my face and wrapped around me give me peace, it flows through those hands into me and they don’t let go till I am calm. -

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity

Club Cultures Music, Media and Subcultural Capital SARAH THORNTON Polity 2 Copyright © Sarah Thornton 1995 The right of Sarah Thornton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 1995 by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Reprinted 1996, 1997, 2001 Transferred to digital print 2003 Editorial office: Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Marketing and production: Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 1JF, UK All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any 3 form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ISBN: 978-0-7456-6880-2 (Multi-user ebook) A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 10.5 on 12.5 pt Palatino by Best-set Typesetter Ltd, Hong Kong Printed and bound in Great Britain by Marston Lindsay Ross International -

In Search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of A

IN SEARCH OF THE AMAZON AMERICAN ENCOUNTERS/GLOBAL INTERACTIONS A series edited by Gilbert M. Joseph and Emily S. Rosenberg This series aims to stimulate critical perspectives and fresh interpretive frameworks for scholarship on the history of the imposing global pres- ence of the United States. Its primary concerns include the deployment and contestation of power, the construction and deconstruction of cul- tural and political borders, the fluid meanings of intercultural encoun- ters, and the complex interplay between the global and the local. American Encounters seeks to strengthen dialogue and collaboration between histo- rians of U.S. international relations and area studies specialists. The series encourages scholarship based on multiarchival historical research. At the same time, it supports a recognition of the represen- tational character of all stories about the past and promotes critical in- quiry into issues of subjectivity and narrative. In the process, American Encounters strives to understand the context in which meanings related to nations, cultures, and political economy are continually produced, chal- lenged, and reshaped. IN SEARCH OF THE AMAzon BRAZIL, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE NATURE OF A REGION SETH GARFIELD Duke University Press Durham and London 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Scala by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in - Publication Data Garfield, Seth. In search of the Amazon : Brazil, the United States, and the nature of a region / Seth Garfield. pages cm—(American encounters/global interactions) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Durr-E-Sameen English Translation

Revised: December 19, 2008 m-dash corrected PRECIOUS PEARLS English translation of Durr-e Sameen (Urdu) By Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Translated by Waheed Ahmad Precious Pearls 3 Translation copyright 2008 by Waheed Ahmad All rights reserved Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Ahmad, Ghulam, 1835-1908 Precious Pearls: English translation of Durr-e Sameen First published in Urdu in 1896 ISBN 1. Ahmad, Waheed II. Title Printed by 4 LIST OF CONTENTS Page 1. Help of God 23 Nusrat-e Ilahi 2. Invitation to ponder 23 Da’wat-e fikr 3. Beneficence of the glorious Quran 23 Fazail-e Quran 4. Addressing the Christians 24 ‘Isaiyoon se khitaab 5. Excellences of the glorious Quran 25 Ausaaf Quran majeed 6. Praise to the Lord of the worlds 26 Hamd Rabbil ‘Alameen 7. The fleeting world 27 Sara-e khaam 8. The Vedas 27 Ved 9. Death of Jesus of Nazareth 28 Wafaat-e Masih Nasri 10. The Signs of near ones 29 ‘Alamaat-il muqarrabeen 11. A plea to God Almighty 29 Qadir Mutlaq ke hazoor 12. Love with Islam and its founder 30 Islam aur bani-e Islam se ‘ishq 13. The Cloak of Baba Nanak 31 Chola Baba Nanak 14. The fruit of Truth 42 Taseer-e sadaqat 15. Mahmood’s Ameen 42 Mahmood ki ameen 16. In the words of Amman Jaan 47 … ba zubaan-e Amman Jaan 17. The Mother of Books 48 Ummul Kitaab 18. Knowledge of God 49 Ma’arfat-e Haq 19. Basheer Ahmad’s Ameen 49 Basheer Ahmad … ki ameen 20. The status of Ahmad of Arabia 58 Shaan-e Ahmad-e ‘Arabi 21. -

ENERGY MASTERMIX – Playlists Vom 21.12.2018

ENERGY MASTERMIX – Playlists vom 21.12.2018 HELMO 1. SPEECHLESS ROBIN SCHULZ FEAT. ERIKA SIROLA 2. SHINE (MASTERMIX) YEARS & YEARS 3. CLOSE NOTD & FELIX JAEHN 4. HIGH ON LIFE MARTIN GARRIX 5. LIKE I LOVE YOU LOST FREQUENCIES 6. STOLEN DANCE MILKY CHANCE 7. WITHOUT ME [ILLENIUM REMIX] HALSEY 8. BODY (MASTERMIX) LOUD LUXARY FEAT. BRANDO 9. LAY ME DOWN (MASTERMIX) AVICII 10. I FOUND YOU (MASTERMIX) BENNY BLANCO & CALVIN HARRIS 11. CLOSE TO ME (MASTERMIX) ELLIE GOULDING & DIPLO FEAT. SWAE LEE 12. SOLO CLEAN BANDIT & DEMI LOVATO 13. CONTROL FEDER 14. GET LUCKY DAFT PUNK FEAT. PHARRELL WILLIAMS 15. SAY MY NAME DAVID GUETTA FEAT. BEBE REXHA & J BALVIN 16. TAKI TAKI DJ SNAKE FEAT. SELENA GOMEZ, CARDI B & OZUNA 17. THIS FEELING THE CHAINSMOKERS 18. SHOW ME LOVE (EDX REMIX) SAM FELDT FEAT. KIMBERLY ANNE 19. PARADISE (MASTERMIX) OFENBACH 20. RIGHT NOW (MASTERMIX) NICK JONAS VS. ROBIN SCHULZ 21. LET YOU LOVE ME (MASTERMIX) RITA ORA 22. DON'T BE SO SHY [FILATOV & KARASIMANY 23. WALK ALONE [ALLE FARBEN REMIX]RUDIMENTAL FEAT. TOM WALKER 24. ELECTRICITY (MASTERMIX) SILK CITY, DUA LIPA FEAT. DIPLO & MARK RONSON 25. HAPPY NOW (MASTERMIX) KYGO FEAT. SANDRO CAVAZZA 26. I GOTTA FEELING (MASTERMIX) BLACK EYED PEASGRIP SEEB & BASTILLE 27. POLAROID JONAS BLUE & LIAM PAYNE 28. CHEERLEADER (FELIX JAEHN MIX) OMI 29. BREAKIN MIDL FING3R 30. REMEDY (MASTERMIX) ALESSO 31. IN MY MIND DYNORO 32. PLAY (MASTERMIX) JAX JONES FEAT. YEARS & YEARS 33. SEXY BACK JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 34. FADING ALLE FARBEN FEAT. ILIRA 35. HIGH HOPES (MASTERMIX) PANIC! AT THE DISCO 36. MOONLIGHT GAULLIN 37. -

Billboard 1974-08-24

NEWSPAPER Bill The International Music -Record -Tape Newsweekly August 24, 1974 $1.25 A Billboard Publication Nixon Furore Slows Davis Calls Texaco Sued In Copyright Movement Promo Slot Tape Piracy Test By MILDRED HALL A Hot Seat By STEPHEN Panasonic Sets By IS HOROWITZ TRAIMAN WASHINGTON -The aftermath NEW YORK -In what may develop as a precedent- setting piracy test case, NEW YORK -Promotion is of the Nixon resignation has set in now Custom Publishing Co. and Camad Music Co. have filed suit against Texaco, Expansion Move second only to aecr as the "hot seal" motion a new series of delays in alleging copyright infringement on songs appearing on tapes alleged to be of the rc nrd industry. Clive Davis Congress for all pending copyright Hy RADCLIFFE JOE bootleg reproductions and sold at an Illinois Texaco station. The oil firm has told an audience of mire than at bills -including the general revision NEW YORK -Panasonic Au- 600 denied the allegations. the opening session of Billboard's bill 5.1361, the House antipiracy bill tomotive Products Dept. will utilize A ruling for the plaintiffs could seventh Annual International Radio H.R. 13364. and the hoped -for ex- network television, as well as trade UA Restructures establish the important precedent in Programming Forum here Wednes- tension legislation to save expiring and consumer print media- in a mas- piracy litigation of a parent com- copyrights. sive promotion campaign that Cal day (14). Into 5 Divisions pany being held liable for actions of Released from the harrowing job Shore, vice president and general The acting Bell Records chief, in By NAT ERI'EDI.AND its agents -in this' case, an ail com- of impeaching a president, both manager of Panasonic's special his first major address to an industry LOS ANGELES- United Artists pany held accountable for activities a the Senate and House began lengthy products division, tails a major in- audience since leaving presi- bas reorganized its non -film oper- of its franchised stations. -

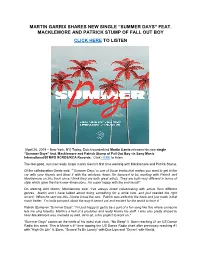

Martin Garrix Shares New Single “Summer Days” Feat

MARTIN GARRIX SHARES NEW SINGLE “SUMMER DAYS” FEAT. MACKLEMORE AND PATRICK STUMP OF FALL OUT BOY CLICK HERE TO LISTEN [April 25, 2019 – New York, NY] Today, Dutch wunderkind Martin Garrix releases his new single “Summer Days” feat. Macklemore and Patrick Stump of Fall Out Boy via Sony Music International/STMPD RCRDS/RCA Records. Click HERE to listen. The feel-good, summer ready single marks Garrix’s first time working with Macklemore and Patrick Stump. Of the collaboration Garrix said: “'’Summer Days’ is one of those tracks that makes you want to get in the car with your friends and blast it with the windows down. I’m honored to be working with Patrick and Macklemore on this track since I think they are both great artists. They are both very different in terms of style which gave the track new dimensions. I’m super happy with the end result!'' On working with Martin, Macklemore said: “I've always loved collaborating with artists from different genres. Martin and I have talked about doing something for a while now, and just needed the right record. When he sent me this, I knew it was the one. Patrick was added to the hook and just made it that much better. I’m hella pumped about the way it turned out and excited for the world to hear it.” Patrick Stump on “Summer Days”: "I’m just happy to get to be a part of a fun song like this where someone lets me sing falsetto. Martin’s a hell of a producer and really knows his stuff. -

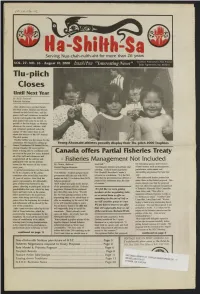

Tlu -Piich Closes Until Next Year by Kelly Foxcrofl Editorial Assistant

MAL I. r t.'. ,:l!i'tiiìr'fr¡'i'Id. OS_oR. 14A- t4 0 a 0 a -NS h r r r Serving Nuu- chah -nulth -aht for more than 26 years Canadian Publications Mail VOL. 27- NO. 16 - August 10, 2000 Product haaitsa "Interesting News" Sales Agreement No. 467510 Sid Tlu -piich Closes Until Next Year By Kelly Foxcrofl Editorial Assistant After athletes have put their hearts t , into their events, families and friends cheered on their loved ones, and the games staff and volunteers scrambled to keep it all together the 2000 Tlu- piich games had come to an end. As quickly as the fun began, on Monday ' afternoon the crowd, athletes, staff V y `?R . and volunteers gathered under the e,' 968 r'' ',y® i ,T canopy of blue sunny skies to cel- y :;r . T .e l' b ebrate the success of the 19th Annual Irk., * ,. t» ':. ,; . : Tlu -piich games. P ''r t ,.ï I. `4.ì :', .:. I(q. p > co-.' I. Y 4 ro R. > ,V o-.'.. W 6:: .R 6. _ z J!.Ç Pricilla Sabbas was the emcee for the . ".... E . .. .. ceremonies who began by calling up Young Ahousaht athletes proudly display their Tlu -piich 2000 Trophies Games Coordinator Ed Samuel for his closing remarks. Ed conveyed his honor at being able to coordinate such an event in the past few years, thanked Canada offers Partial Fisheries Treaty all of his staff and volunteers and congratulated all the athletes and - Fisheries Management Included participants who are the primary Not reason for the success of the events By Denise Ambrose least half" for remaining species and fisheries- every year. -

RSD List 2020

Artist Title Label Format Format details/ Reason behind release 3 Pieces, The Iwishcan William Rogue Cat Resounds12" Full printed sleeve - black 12" vinyl remastered reissue of this rare cosmic, funked out go-go boogie bomb, full of rapping gold from Washington D.C's The 3 Pieces.Includes remixes from Dan Idjut / The Idjut Boys & LEXX Aashid Himons The Gods And I Music For Dreams /12" Fyraften Musik Aashid Himons classic 1984 Electonic/Reggae/Boogie-Funk track finally gets a well deserved re-issue.Taken from the very rare sought after album 'Kosmik Gypsy.The EP includes the original mix, a lovingly remastered Fyraften 2019 version.Also includes 'In a Figga of Speech' track from Kosmik Gypsy. Ace Of Base The Sign !K7 Records 7" picture disc """The Sign"" is a song by the Swedish band Ace of Base, which was released on 29 October 1993 in Europe. It was an international hit, reaching number two in the United Kingdom and spending six non-consecutive weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States. More prominently, it became the top song on Billboard's 1994 Year End Chart. It appeared on the band's album Happy Nation (titled The Sign in North America). This exclusive Record Store Day version is pressed on 7"" picture disc." Acid Mothers Temple Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (Title t.b.c.)Space Age RecordingsDouble LP Pink coloured heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP Not previously released on vinyl Al Green Green Is Blues Fat Possum 12" Al Green's first record for Hi Records, celebrating it's 50th anniversary.Tip-on Jacket, 180 gram vinyl, insert with liner notes.Split green & blue vinyl Acid Mothers Temple & the Melting Paraiso U.F.O.are a Japanese psychedelic rock band, the core of which formed in 1995.The band is led by guitarist Kawabata Makoto and early in their career featured many musicians, but by 2004 the line-up had coalesced with only a few core members and frequent guest vocalists. -

Record-Senate. Aprd.J 4

2678 CONGRESSION~ RECORD-SENATE. APRD.J 4, Also, petition of ..Aaron Royston, of .Marshall County, Mississippi, for ..Also, petition of James W. Snyder, Jefferson County, West Virginia, reference of his claim to the Court of Claims-to the Committee on for reference of his claim to the Court of Claims-to the Committee on War Claims. War Claims. By Mr. MORRILL: Petition of M. H. Roller and 60 others, of Cir cleville, ·Kans., asking that the tax on flaxseed and linseed-oil be re The following petitions for an increase of compensation of fourth tained-to the Committee on Ways and Means. class postmasters were severally referred to tho Committee on the Post By Mr. MORROW: Petition of citizens of San Francisco, Cal., against Office and Post-Roads: the repeal of the tariff on chrome iron-to the Committee on Wa.ys and By :Mr. BANKHEAD: Of J. L.Wrightandothers, of Webster County, Me.o1.ns. Alabama. By Mr. MORSE: Petition of 23 citizens of Boston, 1\Iass., for better By Mr. OATES: Of Thomas D. McGough and 27 others, citizens of mail facilit.ies between Boston and New York, etc.-to the Committee Glennville, Ala. on the Post-Office and Post-Roads. By Mr. NEAL: Petition of J. A. Turley ru1d 14 others, citizens of The following petitions, indorsing the per diem rated service-pension McMinn County, Tennessee, for a special-act pension to Robert Pearce, bill, based on the principle of paying all soldiers, sailors, and marines late a private in Company ..A, Tenth Regiment Tennessee Cavalry- of the late war a monthly pension of 1 cent a day for each day they to the Oommittee on Invalid Pensions.