A Description and Linguistic Analysis of the Tai Khuen Writing System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2773 Date: 2004-06-15

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2773 Date: 2004-06-15 ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Coded Character Set Secretariat: Japan (JISC) Doc. Type: Draft disposition of comments Title: Draft disposition of comments on SC2 N 3714 (PDAM text for Amendment 1 to ISO/IEC 10646:2003) Source: Michel Suignard (project editor) Project: JTC1 02.10646.00.01 Status: For review by WG2 Date: 2004-06-15 Distribution: WG2 Reference: SC2 N3714, N3730, N3731, Medium: Paper, PDF file Comments were received from Canada, China, Ethiopia(O), France, Ireland, Morroco, Tunisia and USA. The following document is the draft disposition of those comments. The disposition is organized per country. Note – The full content of the ballot comments (minus some character glyphs) have been included in this document to facilitate the reading. The dispositions are inserted in between these comments and are marked in Underlined Bold Serif text, with explanatory text in italicized italic serif. Note – This ballot has generated many requests for character addition to existing blocks or even requests for completely new scripts such as Tifinagh. The working group needs to make decision when approving these new characters to: • either incorporate them in the currently balloted amendment, • or incorporate them in a new amendment with the consideration that the current amendment has only one technical round left. Page 1 of 16 Canada: Yes with comments: Technical Comments: Comment a: "Canada accepts the text of the PDAM1 as written. Also Canada requests that the following proposed additions to be approved by WG2 and included in this amendment before it progresses to the next stage: JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2739, a joint Morocco-Canada-France proposal to add Tifinagh script WG2 discussion To be discussed in ad hoc meeting. -

A Practical Sanskrit Introductory

A Practical Sanskrit Intro ductory This print le is available from ftpftpnacaczawiknersktintropsjan Preface This course of fteen lessons is intended to lift the Englishsp eaking studentwho knows nothing of Sanskrit to the level where he can intelligently apply Monier DhatuPat ha Williams dictionary and the to the study of the scriptures The rst ve lessons cover the pronunciation of the basic Sanskrit alphab et Devanagar together with its written form in b oth and transliterated Roman ash cards are included as an aid The notes on pronunciation are largely descriptive based on mouth p osition and eort with similar English Received Pronunciation sounds oered where p ossible The next four lessons describ e vowel emb ellishments to the consonants the principles of conjunct consonants Devanagar and additions to and variations in the alphab et Lessons ten and sandhi eleven present in grid form and explain their principles in sound The next three lessons p enetrate MonierWilliams dictionary through its four levels of alphab etical order and suggest strategies for nding dicult words The artha DhatuPat ha last lesson shows the extraction of the from the and the application of this and the dictionary to the study of the scriptures In addition to the primary course the rst eleven lessons include a B section whichintro duces the student to the principles of sentence structure in this fully inected language Six declension paradigms and class conjugation in the present tense are used with a minimal vo cabulary of nineteen words In the B part of -

The Festvox Indic Frontend for Grapheme-To-Phoneme Conversion

The Festvox Indic Frontend for Grapheme-to-Phoneme Conversion Alok Parlikar, Sunayana Sitaram, Andrew Wilkinson and Alan W Black Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, USA aup, ssitaram, aewilkin, [email protected] Abstract Text-to-Speech (TTS) systems convert text into phonetic pronunciations which are then processed by Acoustic Models. TTS frontends typically include text processing, lexical lookup and Grapheme-to-Phoneme (g2p) conversion stages. This paper describes the design and implementation of the Indic frontend, which provides explicit support for many major Indian languages, along with a unified framework with easy extensibility for other Indian languages. The Indic frontend handles many phenomena common to Indian languages such as schwa deletion, contextual nasalization, and voicing. It also handles multi-script synthesis between various Indian-language scripts and English. We describe experiments comparing the quality of TTS systems built using the Indic frontend to grapheme-based systems. While this frontend was designed keeping TTS in mind, it can also be used as a general g2p system for Automatic Speech Recognition. Keywords: speech synthesis, Indian language resources, pronunciation 1. Introduction in models of the spectrum and the prosody. Another prob- lem with this approach is that since each grapheme maps Intelligible and natural-sounding Text-to-Speech to a single “phoneme” in all contexts, this technique does (TTS) systems exist for a number of languages of the world not work well in the case of languages that have pronun- today. However, for low-resource, high-population lan- ciation ambiguities. We refer to this technique as “Raw guages, such as languages of the Indian subcontinent, there Graphemes.” are very few high-quality TTS systems available. -

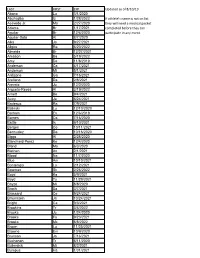

LAST FIRST EXP Updated As of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If Athlete's Name Is Not on List Acevedo Jr

LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Abano Lu 3/1/2020 Abuhadba Iz 1/28/2022 If athlete's name is not on list Acevedo Jr. Ma 2/27/2020 they will need a medical packet Adams Br 1/17/2021 completed before they can Aguilar Br 12/6/2020 participate in any event. Aguilar-Soto Al 8/7/2020 Alka Ja 9/27/2021 Allgire Ra 6/20/2022 Almeida Br 12/27/2021 Amason Ba 5/19/2022 Amy De 11/8/2019 Anderson Ca 4/17/2021 Anderson Mi 5/1/2021 Ardizone Ga 7/16/2021 Arellano Da 2/8/2021 Arevalo Ju 12/2/2020 Argueta-Reyes Al 3/19/2022 Arnett Be 9/4/2021 Autry Ja 6/24/2021 Badeaux Ra 7/9/2021 Balinski Lu 12/10/2020 Barham Ev 12/6/2019 Barnes Ca 7/16/2020 Battle Is 9/10/2021 Bergen Co 10/11/2021 Bermudez Da 10/16/2020 Biggs Al 2/28/2020 Blanchard-Perez Ke 12/4/2020 Bland Ma 6/3/2020 Blethen An 2/1/2021 Blood Na 11/7/2020 Blue Am 10/10/2021 Bontempo Lo 2/12/2021 Bowman Sk 2/26/2022 Boyd Ka 5/9/2021 Boyd Ty 11/29/2021 Boyzo Mi 8/8/2020 Brach Sa 3/7/2021 Brassard Ce 9/24/2021 Braunstein Ja 10/24/2021 Bright Ca 9/3/2021 Brookins Tr 3/4/2022 Brooks Ju 1/24/2020 Brooks Fa 9/23/2021 Brooks Mc 8/8/2022 Brown Lu 11/25/2021 Browne Em 10/9/2020 Brunson Jo 7/16/2021 Buchanan Tr 6/11/2020 Bullerdick Mi 8/2/2021 Bumpus Ha 1/31/2021 LAST FIRST EXP Updated as of 8/10/19 Burch Co 11/7/2020 Burch Ma 9/9/2021 Butler Ga 5/14/2022 Byers Je 6/14/2021 Cain Me 6/20/2021 Cao Tr 11/19/2020 Carlson Be 5/29/2021 Cerda Da 3/9/2021 Ceruto Ri 2/14/2022 Chang Ia 2/19/2021 Channapati Di 10/31/2021 Chao Et 8/20/2021 Chase Em 8/26/2020 Chavez Fr 6/13/2020 Chavez Vi 11/14/2021 Chidambaram Ga 10/13/2019 -

418338 1 En Bookbackmatter 205..225

Glossary Abhayamudra A style of keeping hands while sitting Abhidhama The Abhidhamma Pitaka is a detailed scholastic reworking of material appearing in the Suttas, according to schematic classifications. It does not contain systematic philosophical treatises, but summaries or enumerated lists. The other two collections are the Sutta Pitaka and the Vinaya Pitaka Abhog It is the fourth part of a composition. The last movement gradually goes back to the sthayi after completion of the paraphrasing and improvisation of the composition, which can cover even three octaves in the recital of a master performer Acharya A teacher or a tutor who is the symbol of wisdom Addhayoga One of seven kinds of lodgings where monks are allowed to live. Addhayoga is a building with a roof sloping on either one side or both. It is shaped like wings of the Garuda Agganna-sutta AggannaSutta is the 27th Sutta of the Digha Nikaya collection. The sutta describes a discourse imparted by the Buddha to two Brahmins, Bharadvaja, and Vasettha, who left their family and caste to become monks Ahankar Haughtiness, self-importance A-hlu-khan mandap Burmese term, a temporary pavilion to receive donation Akshamala A japa mala or mala (meaning garland) which is a string of prayer beads commonly used by Hindus, Buddhists, and some Sikhs for the spiritual practice known in Sanskrit as japa. It is usually made from 108 beads, though other numbers may also be used Amulets An ornament or small piece of jewellery thought to give protection against evil, danger, or disease. Clay tablets have also been used as amulets. -

The Original Pronunciation of Sanskrit Devanàgará – Transliteration – IPA-Symbols

The Original Pronunciation of Sanskrit DevanÀgarÁ – Transliteration – IPA-Symbols $ a n$D À DØ i L Á LØ u X A Â XØ ? Ã `C C Å `CØ CØ Æ O C # e HØ #H ai DeØ, $DH o RØ $D( au DØe8 N{ k N R kh N+ J g J gh J+ Ç 1 F c WeÝ ' ch WeÝ+ M j GeÛ + jh GeÛ+ _ È × T Ê Þ 4 Êh Þ+ I Ë É ) Ëh É+ > É Ö W t W Z th W+ G{ d G [ dh G+ Q n Q S p S { ph S+ E b E bh E+ P m P \ y M U{ r `O l O Y v Y9 ] Ì Ý Í V s V K h Ù Drafted by Maciej Zieba and Ulrich Stiehl under the auspices of Manfred Mayrhofer. ! Ï [ Improvements by Jost Gippert, Madhav Deshpande, Sunder Hattangadi, John Smith and others. This chart is a compromise, since the original pronunciation of Sanskrit Î YDULRXV is not exactly known in every detail. – 06/09/2002/us. Notes: 1. $ seems to have been pronounced originally as [n] or as [], possibly never as [D]. Not even the pronunciation of this most often used letter $ is exactly known! 2. The original pronunciation of is not known. It occurs only in the verb dS(kÆp). 3. U{seems to have been pronounced as [`] or as [], and likewise the liquid seems to have been pronounced as syllabic [`C] (notation: [`]+ [ C]) or as syllabic [C]. 4. The pronunciation of the semi-vowel Y seems to have been either [Y] or [9]. -

The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes

Portland State University PDXScholar Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Fariborz Maseeh Department of Mathematics Publications and Presentations and Statistics 3-2018 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hu Sun University of Macau Christine Chambris Université de Cergy-Pontoise Judy Sayers Stockholm University Man Keung Siu University of Hong Kong Jason Cooper Weizmann Institute of Science SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Sun X.H. et al. (2018) The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes. In: Bartolini Bussi M., Sun X. (eds) Building the Foundation: Whole Numbers in the Primary Grades. New ICMI Study Series. Springer, Cham This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors Xu Hu Sun, Christine Chambris, Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper, Jean-Luc Dorier, Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued, Eva Thanheiser, Nadia Azrou, Lynn McGarvey, Catherine Houdement, and Lisser Rye Ejersbo This book chapter is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mth_fac/253 Chapter 5 The What and Why of Whole Number Arithmetic: Foundational Ideas from History, Language and Societal Changes Xu Hua Sun , Christine Chambris Judy Sayers, Man Keung Siu, Jason Cooper , Jean-Luc Dorier , Sarah Inés González de Lora Sued , Eva Thanheiser , Nadia Azrou , Lynn McGarvey , Catherine Houdement , and Lisser Rye Ejersbo 5.1 Introduction Mathematics learning and teaching are deeply embedded in history, language and culture (e.g. -

Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe Romanization: KNAB 2012

Institute of the Estonian Language KNAB: Place Names Database 2012-10-11 Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe romanization: KNAB 2012 I. Consonant characters 1 ᦀ ’a 13 ᦌ sa 25 ᦘ pha 37 ᦤ da A 2 ᦁ a 14 ᦍ ya 26 ᦙ ma 38 ᦥ ba A 3 ᦂ k’a 15 ᦎ t’a 27 ᦚ f’a 39 ᦦ kw’a 4 ᦃ kh’a 16 ᦏ th’a 28 ᦛ v’a 40 ᦧ khw’a 5 ᦄ ng’a 17 ᦐ n’a 29 ᦜ l’a 41 ᦨ kwa 6 ᦅ ka 18 ᦑ ta 30 ᦝ fa 42 ᦩ khwa A 7 ᦆ kha 19 ᦒ tha 31 ᦞ va 43 ᦪ sw’a A A 8 ᦇ nga 20 ᦓ na 32 ᦟ la 44 ᦫ swa 9 ᦈ ts’a 21 ᦔ p’a 33 ᦠ h’a 45 ᧞ lae A 10 ᦉ s’a 22 ᦕ ph’a 34 ᦡ d’a 46 ᧟ laew A 11 ᦊ y’a 23 ᦖ m’a 35 ᦢ b’a 12 ᦋ tsa 24 ᦗ pa 36 ᦣ ha A Syllable-final forms of these characters: ᧅ -k, ᧂ -ng, ᧃ -n, ᧄ -m, ᧁ -u, ᧆ -d, ᧇ -b. See also Note D to Table II. II. Vowel characters (ᦀ stands for any consonant character) C 1 ᦀ a 6 ᦀᦴ u 11 ᦀᦹ ue 16 ᦀᦽ oi A 2 ᦰ ( ) 7 ᦵᦀ e 12 ᦵᦀᦲ oe 17 ᦀᦾ awy 3 ᦀᦱ aa 8 ᦶᦀ ae 13 ᦺᦀ ai 18 ᦀᦿ uei 4 ᦀᦲ i 9 ᦷᦀ o 14 ᦀᦻ aai 19 ᦀᧀ oei B D 5 ᦀᦳ ŭ,u 10 ᦀᦸ aw 15 ᦀᦼ ui A Indicates vowel shortness in the following cases: ᦀᦲᦰ ĭ [i], ᦵᦀᦰ ĕ [e], ᦶᦀᦰ ăe [ ∎ ], ᦷᦀᦰ ŏ [o], ᦀᦸᦰ ăw [ ], ᦀᦹᦰ ŭe [ ɯ ], ᦵᦀᦲᦰ ŏe [ ]. -

The Kharoṣṭhī Documents from Niya and Their Contribution to Gāndhārī Studies

The Kharoṣṭhī Documents from Niya and Their Contribution to Gāndhārī Studies Stefan Baums University of Munich [email protected] Niya Document 511 recto 1. viśu͚dha‐cakṣ̄u bhavati tathāgatānaṃ bhavatu prabhasvara hiterṣina viśu͚dha‐gātra sukhumāla jināna pūjā suchavi paramārtha‐darśana 4 ciraṃ ca āyu labhati anālpakaṃ 5. pratyeka‐budha ca karoṃti yo s̄ātravivegam āśṛta ganuktamasya 1 ekābhirāma giri‐kaṃtarālaya 2. na tasya gaṃḍa piṭakā svakartha‐yukta śamathe bhavaṃti gune rata śilipataṃ tatra vicārcikaṃ teṣaṃ pi pūjā bhavatu [v]ā svayaṃbhu[na] 4 1 suci sugaṃdha labhati sa āśraya 6. koḍinya‐gotra prathamana karoṃti yo s̄ātraśrāvaka {?} ganuktamasya 2 teṣaṃ ca yo āsi subha͚dra pac̄ima 3. viśāla‐netra bhavati etasmi abhyaṃdare ye prabhasvara atīta suvarna‐gātra abhirūpa jinorasa te pi bhavaṃtu darśani pujita 4 2 samaṃ ca pādo utarā7. imasmi dāna gana‐rāya prasaṃṭ́hita u͚tama karoṃti yo s̄ātra sthaira c̄a madhya navaka ganuktamasya 3 c̄a bhikṣ̄u m It might be going to far to say that Torwali is the direct lineal descendant of the Niya Prakrit, but there is no doubt that out of all the modern languages it shows the closest resemblance to it. [...] that area around Peshawar, where [...] there is most reason to believe was the original home of Niya Prakrit. That conclusion, which was reached for other reasons, is thus confirmed by the distribution of the modern dialects. (Burrow 1936) Under this name I propose to include those inscriptions of Aśoka which are recorded at Shahbazgaṛhi and Mansehra in the Kharoṣṭhī script, the vehicle for the remains of much of this dialect. To be included also are the following sources: the Buddhist literary text, the Dharmapada found in Khotan, written likewise in Kharoṣṭhī [...]; the Kharoṣṭhī documents on wood, leather, and silk from Caḍ́ota (the Niya site) on the border of the ancient kingdom of Khotan, which represented the official language of the capital Krorayina [...]. -

Sanskrit Alphabet

Sounds Sanskrit Alphabet with sounds with other letters: eg's: Vowels: a* aa kaa short and long ◌ к I ii ◌ ◌ к kii u uu ◌ ◌ к kuu r also shows as a small backwards hook ri* rri* on top when it preceeds a letter (rpa) and a ◌ ◌ down/left bar when comes after (kra) lri lree ◌ ◌ к klri e ai ◌ ◌ к ke o au* ◌ ◌ к kau am: ah ◌ं ◌ः कः kah Consonants: к ka х kha ga gha na Ê ca cha ja jha* na ta tha Ú da dha na* ta tha Ú da dha na pa pha º ba bha ma Semivowels: ya ra la* va Sibilants: sa ш sa sa ha ksa** (**Compound Consonant. See next page) *Modern/ Hindi Versions a Other ऋ r ॠ rr La, Laa (retro) औ au aum (stylized) ◌ silences the vowel, eg: к kam झ jha Numero: ण na (retro) १ ५ ॰ la 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 @ Davidya.ca Page 1 Sounds Numero: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910 १॰ ॰ १ २ ३ ४ ६ ७ varient: ५ ८ (shoonya eka- dva- tri- catúr- pancha- sás- saptán- astá- návan- dásan- = empty) works like our Arabic numbers @ Davidya.ca Compound Consanants: When 2 or more consonants are together, they blend into a compound letter. The 12 most common: jna/ tra ttagya dya ddhya ksa kta kra hma hna hva examples: for a whole chart, see: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/devanagari_conjuncts.php that page includes a download link but note the site uses the modern form Page 2 Alphabet Devanagari Alphabet : к х Ê Ú Ú º ш @ Davidya.ca Page 3 Pronounce Vowels T pronounce Consonants pronounce Semivowels pronounce 1 a g Another 17 к ka v Kit 42 ya p Yoga 2 aa g fAther 18 х kha v blocKHead -

Indic Loanwords In Tocharian B, Local Markedness, And The Animacy

Indic Loanwords in Tocharian B, Local Markedness, and the Animacy Hierarchy Francesco Burroni and Michael Weiss (Department of Linguistics, Cornell University) A question that is rarely addressed in the literature devoted to Language Contact is: how are nominal forms borrowed when the donor and the recipient language both possess rich inflectional morphology? Can nominal forms be borrowed from and in different cases? What are the decisive factors shaping the borrowing scenario? In this paper, we frame this question from the angle of a case study involving two ancient Indo-European languages: Tocharian and Indic (Sanskrit, Prakrit(s)). Most studies dedicated to the topic of loanwords in Tocharian B (henceforth TB) have focused on borrowings from Iranian (e.g. Tremblay 2005), but little attention has been so far devoted to forms borrowed from Indic, perhaps because they are considered uninteresting. We argue that such forms, however, are of interest for the study of Language Contact. A remarkable feature of Indic borrowings into TB is that a-stems are borrowed in TB as e-stems when denoting animate referents, but as consonant (C-)stems when denoting inanimate referents, a distribution that was noticed long ago by Mironov (1928, following Staёl-Holstein 1910:117 on Uyghur). In the literature, however, one finds no reaction to Mironov’s idea. By means of a systematic study of all the a-stems borrowed from Indic into TB, we argue that the trait [+/- animate] of the referent is, in fact, a very good predictor of the TB shape of the borrowing, e.g. male personal names from Skt. -

Myanmar Script Learning Guide Burmese 1,2,3 Tone System Is Developed by Naing Tin-Nyunt-Pu Copyright © 2013-2017, Naing Tinnyuntpu & Asia Pearl Travels

Myanmar Script Learning guide (Revision F) by Naing Tinnyuntpu WITH FREE ONLINE AUDIO SUPPORT https://www.asiapearltravels.com/language/myanmar-script-learning-guide.php 1 of 104 Menu ≡ Introduction ........................................................................................4 Vowel: A .............................................................................................6 Vowel: E or I ....................................................................................13 Vowel: U ..........................................................................................20 Vowel: O ..........................................................................................24 Vowel: Ay .........................................................................................28 Vowel: Au ........................................................................................33 Vowel: Un or An ..............................................................................37 Vowel: In ..........................................................................................42 Vowel: Eare ......................................................................................46 Vowel: Ain .......................................................................................51 Vowel: Ome .....................................................................................53 Vowel: Ine ........................................................................................56 Vowel: Oon ......................................................................................59